(If you have not played The Walking Dead up through the season finale, do not read this. Spoilers abound!)

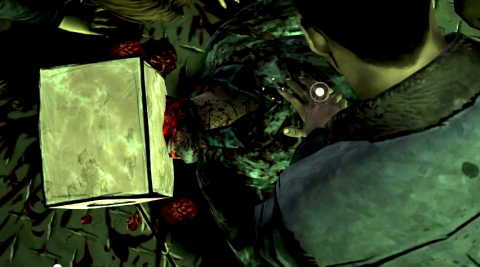

We reached the end of the road for Lee Everett's journey in the final episode of Telltale Games' The Walking Dead. The precise details of that conclusion were yours to make. For the record, I regret my last decision. Sorry, Clem.

I've appreciated the hours Telltale and its designers and writers have spent with me since The Walking Dead premiered last April, and surprised the living hell out of us. There's no reason to flog Jurassic Park for the umpteenth time, but isn't it amazing how far in our collective rear-view mirror that game is now?

Not everything about The Walking Dead's final episode clicked (it surprised me how much Telltale loves the stranger conversation, a moment that's proven a bit divisive amongst players), but the moment that really counted, the final conversation with Lee and Clementine, was perfect. Perfectly brutal, anyway.

For our final conversation, an examination of episode five, No Time Left, I was joined by not only series designers Sean Vanaman and Jake Rodkin, but Telltale co-founder and CTO Kevin Bruner. We walk through the company's response to the somewhat overwhelming critical acclaim, what it was like to build each of this episode's big moments, and even touch on structuring the game's epilogue. What does it mean for the future? Find out.

- Faces of Death, Part 1: A New Day

- Faces of Death, Part 2: Starved For Help

- Faces of Death, Part 3: Long Road Ahead

- Faces of Death, Part 4: Around Every Corner

GIant Bomb: You guys just won Game of the Year at the Spike VGAs, and other game of the year stuff is happening. How are you guys processing all of this?

Kevin Bruner: Hmm. [pause] Slowly.

Sean Vanaman: I think, actually, I blocked out 24 hours of my life where I thought about it and talked to people about it, and now it just didn't happen. It's the way I operate, it's completely compartmentalized. Working on new stuff, in a lot of meetings, and it's just…you know. But that's just me personally, not the studio.

Bruner: I think we're really happy. We started making episodic games and trying to revive adventure games from a place where they weren't game of the year games, and it's been a long road. It's really nice to be acknowledged at all, let alone in this giant way, where everybody seems to really like the game.

Vanaman: [It's] an episodic game, a licensed game, a downloadable game--all the things that the studio is so passionate about, but it's definitely not a mainstream model. I think that actually helps. It makes it more surreal. [laughs] It makes it more "did it it actually happen?" It's cool to have done it.

Rodkin: We had a good sports-movie arc for this year, I think. It's nice.

GB: You guys are Rudy?

Vanaman: Yeah, there was definitely a Rudy moment. Yeah.

Group: [laughs]

Vanaman: We just got better. We kept working, you know? I think that's really awesome. It wasn't the fact that Telltale said "oh, the hell with it, we're making an 12-hour retail game--go!" And, then, "oh, finally--recognition." No, we actually believed in the things that we were doing, and did it well. It's really cool.

Bruner: Also, [it's] good for the future because it's been a diligent road here, and the teams are moving forward with all of our next stuff. We're finding what we're doing, and continuing the process.

GB: When you guys sat down to start writing episode five…Sean, I think I saw you in person as you were trying to finish up getting that script together. What was that process like? What was it like sitting down to write this one, where it all and to come to a head? How was it any different from writing the earlier episodes?

Rodkin: Gosh. I would describe episode five's internal events, as opposed to external events, which is a race against time to achieve the impossible. The vehicle that is The Walking Dead was on fire during most of the end, until we hit the finish line. I don't know.

Vanaman: Yeah. I mean, it sort of helped. We had four episodes out, we knew what we did well, we knew what we didn't do well, we knew what people were emotionally responsive to, we learned from a number of mistakes, but we definitely knew the finish line wasn't moving for a lot of reasons. [laughs] It put us into a heightened sense of urgency. Everybody in the studio knew the basics of how this thing ended, but [we] sat in a room before I went off to write with [a bunch of the team] and just walked through the story. We talked about there being eight multiple first acts, based on who was with you, talked about cutting the arm off or not. Everybody had their concerns about the amount of branching that was going to happen, but everybody felt it was the right end to the story, and it felt emotionally right. So we just threw ourselves at it, and wrote that in a way that was pretty reckless, to be honest. [laughs]

Everybody just did their jobs incredibly well. It was one of those situation where, because so much was going on at the same time, I just went into a cave, and wrote and wrote and wrote and wrote, and sent around the high-risk passages to the guys who had been on the game the whole time. I always try to do that, try to show people things--"oh, this is the scene where this happens, this is the scene where you meet the stranger, this is the scene where you x, y, z."

Making sure that people, everybody on the team, is into it. There are definitely days in my life I don't quite remember. [laughs] But the cool thing is, it's episodic, right? We already know the stakes. We're trying not to make the same mistakes twice. We're now finally all on the same page from just our gut instincts. Everyone at the studio is just making the decisions that will allow us to make the game good. We developed a shorthand by that time that was really nice, it was a nice security blanket for when you have to pretend people aren't just waiting on a script.

Rodkin: As is always the case with our production, we became the most well-oiled, crazy machine. We could make Walking Dead games in our sleep by the end of it. Just in time to no longer make them. [laughs] We're going right from this onto the Fables game that we're doing because it's the same company and the same folks.

Bruner: If you want to continue the sports metaphor, this was like the last drive, and everybody was just really tuned in, doing their jobs really well, and everybody playing positions perfectly to pull it off. It was really nice to have a team and organization to pull it all together as fast as we did.

GB: That first decision, right off the bat, can play out in a bunch of different ways, depending on how episode four ended for you. When presented with the decision to cut your hand, my first thought was "christ, not again" because the game has trained me to cut shit off in the past. At that point, I feel like I'd been trained to just cut it off. There was no hesitation. The first time, I hesitated. This time, I just cut that shit off.

Rodkin: Just out of curiosity, Patrick, were you by yourself or did you have people with you?

GB: I had everyone, but [Brad Shoemaker] had no one.

Rodkin: Wow. So Brad's experience was that he was just alone and had to cut his own arm off by himself, and doing the actual cutting, but you had the conversation with the group?

GB: Yeah, so we had the most polar opposite situation. When we were talking through the episodes during our game of the year discussions, his impression was, since some of the other characters come in later in the episode anyway, he just thought that's how it plays out for everybody. He had no idea that very first moment played out completely differently.

Rodkin: Yeah, [episode] four kind of rolls all the way back to things you did throughout [the season]. By the end of four, the group ripples out with decisions that were right in that conversation, and decisions you made all the way in episode one. I was really happy with the way Gary and the guys pulled that off in four.

Bruner: One of the cool things about five is that there's a lot of different ways five can start, but the game doesn't wear it on its sleeve from a storytelling point-of-view, kind of like some other choice-driven games or branching games do. There's a screen at the end of four that shows you all the different possibilities and where you fit in, but when you play through, it just feels like your story. You feel like "wow, there's another version of this story that could have six other different characters in it," It feels really organic.

Rodkin: I'm really happy you and Brad had a super different experience, but didn't know the other way the game would work because, like you said, we hit you over the head with it at the end of four. So, going into the season finale, we really wanted to have that opening of episode five to feel like it was the beginning of your personal season finale. We wanted people to focus on the moment, and not really on the craziness. But to achieve that, we probably had to make the most crazy scene that we built in the entire game. I think act one of episode five had something like 16 different combinations that can maybe, at some point, turn into 32? Do you cut your arm off? Did you lie about the bite? Is Ben alive? The actual act one of episode five was…we knew going in that we wanted it to be the madness. It's not that there's actually 32 different openings to the game, but there are all these different components that can multiply. The game weaves it all together as it goes at a very small level.

Bruner: Rather than do it "the aliens win or lose!" We really try to sweat the little details, and make sure the game feels organic and is aware of the situation.

Vanaman: It's all of those things. There's a one-in-eight chance that you're with a certain collection of people, but there's a three-in-eight chance that you're with a collection of two people. But then there's a one-in-two chance that you did one thing, there's a one-in-two chance you did another. Add all those things together. […] That's the devil-in-the-details challenge. Of all the writing, I think I spent half of my time on the first act, when, really, the dramatic meat of the game is in the third. But I spent half of my man hours on that first half just making sure it [made sense]. And there were a couple places where I went ughhhh, and missed one.

Rodkin: We think players really feel the details like that, especially when you're at the end of the story and everything's adding up.

GB: I was looking at the stats and it was split basically 25/75. What do you suspect the motivations were for the players that chose to keep the arm? Or what motivations did you put into the dialogue to suggest players should hold onto it?

Rodkin: I think we thought there would be some people who would be in denial, and would think that if Lee keeps his arm, there's a tiny chance that they'll get a happy ending, which doesn't exist. I think there were some people who knew they were going out but thought "if I keep the arm, I'm probably still going to die, but I'll have a better chance of getting to Clementine if I have two actual hands."

Vanaman: And, also, just fear. We're just gonna give them this thing and, "oh, I'll trust them to not screw me over." I think that's a big part of it. I actually think the writing at the beginning of it, when he's talking about it…I kind of wish I had another bite at that apple. I don't think it's…I don't think it's as good as it could have been.

Rodkin: We took a few design routes on chopping off the arm. We simplified it very much down to just that "do you wanna chop the arm off or not?" But there was a lot of things in this game where we floated around a lot and ended up chopping everything away--oops, that's lame analogy--but [this is] just down to "just do it or don't."

Bruner: We wanted it to be more visceral thing than strategic. Strategic in the franchise sense, not "oh, it's going to let me solve a puzzle or accomplish something later."

Rodkin: Yeah, stripping the meaning out of it. It puts the onus on players to figure out what it means for them to cut off their arm or not. Whereas if Lee says "I'll be more agile with two arms than but with one arm the disease may spread slower!" [laughs] But we didn't want to put that stuff in there specifically because we've found, over the course of this game, that players ascribe a lot of meaning to these choices themselves, so we can't get away with not saying a lot, especially towards the end of the story. That's really awesome.

Bruner: Trust the player.

GB: Did you take any lessons from that moment in the beginning of episode two, in terms of how you frame that choice?

Vanaman: There were definitely some design decisions. The decision to cut your own arm off is more measured and evenly weighted, and it's in design, systems design, and it's right there in the UI. We, again, if we go back to episode two…

Rodkin: The reticule being right on top of the leg was funky.

Vanaman: If it was just three inches to the left...

Rodkin: The leg chop in episode two was more about this frantic moment where you have all these things you can try, and the thing you don't want to do is cut off the arm…but zombies are coming! There was a conscious decision that everyone arrived at with episode five to make it feel different than episode two. It's about what it means, not "do you have to do it?" That choice is one of the few binary choices of the season that doesn't have a timer on it. If you're alone, you can walk up to the tool and just stand there and contemplate and leave. He just looks at his arm. We wanted that one to have a different feel because we already chopped off one limb.

Vanaman: Yeah, definitely. The thing we knew to keep, though, is once it happens, make you feel it.

Rodkin: You chop off a lot of legs in a lot of games, and we know that people responded really, really well to just getting down and dirty with that leg. [pause] I gotta go. [laughs]

Vanaman: It can't be clean, it can't be easy. It needs to have specificity of pain, I guess, is the thing we learned?

Rodkin: That said, as it's happening to you, we've made a really conscious directorial choice to not actually focus on the gore of that arm. I mean, we built it! Our modelers got to relish the details of this arm, but whether you're alone or whether you're with the group, you only get one, one-and-a-half of a glimpse.

Vanaman: When you're alone! [laughs]

Rodkin: Oh, you're right. When you're alone, you just see the arm flop off. [laughs]

Bruner: That's one of my favorite things when you're with the group. It just came out of the directorial of it…from Sean Ainsworth, I guess?

Rodkin: Nick Herman, the director of episode four, put that scene together.

Bruner: But when you're with the group, you chop the arm off, and you just see Lee wince, and then there's the next shot. You just see a little, tiny sliver--the arm laying on the floor--for like three-quarters of a second, and that's it, that's all the game gives you. It's done, it's over, move on.

Rodkin: When you're by yourself, you're right, Sean, that when you cut off your own arm, that it is a little heavier.

My favorite one, and it's one of the rarest playthroughs, but when Lee and Ben are the only people left, and there's no one else to do it, Ben's like "I'll do it, I'll do it, I got you, I got this, I'll cut off your arm." And then he sees a little bit of blood, and just passes out immediately. [laughs] No one's there to step up. There's a few other fun character things. You saw Kenny and Christa, where Kenny starts to take charge and gets squeamish. if Kenny's alone, he'll do it, but if he has the opportunity to wuss out, he will. We tried to leave a lot of variance in that. There's one really weird one where you can decide to tear off your sleeve, but then back out because you're by yourself, and then Lee just has one exposed, ripped, beefy arm for the game. [laughs] The rarest combo. I don't know how many people actually have done that. [laughs]

GB: Cutting off the arm or not cutting off the arm, it seems like some of the motivation comes from implying a bit of false hope to the player. Throughout the series, there's definitely this theme of having to believe in false hope as a motivator to keep going, but do you consciously keep that in mind?

Rodkin: The act of making the choice in the moment is one of the things that we put a lot of value into. Looking back at what it actually meant, sometimes the choice changes your life, sometimes the choice changes your relationship, and sometimes it was your fault or not. And that's a thing we tried to explore in this game a lot. Whatever your feeling is in hindsight, in the moment, it always means a lot. In cutting off your arm, we play with that. We tried to play with that over the course of the episode. If you leave your arm on, the infection keeps spreading, and Lee blacks out all over the place, which is subtle. If you have a stumpy arm, everyone is very surprised by your stumpy arm. [laughs] At the end of the day, Lee still dies, but our hope is that when you're sitting there thinking about it, you think about "what would I do in this situation? What would myself, as a real human being, do if I was right here in this clearly improbable place?" That's where we find a lot of interest.

Vanaman: I completely agree. I was going to exactly say that verbatim. I don't think we ever talked about hope in the moment, but we talk about something close to that, which is, as a player, as a human being emotionally in the situation, what do I wish I could do? And, then, explore that. That, obviously, is founded in hope for Lee, but we're not in the writers room going "we need to give Lee hope here!" It's more…what, as a human being, [do they] wish they could do? And let's explore that out, and see where it takes us.

Bruner: It's what's available to you in the situation. In The Walking Dead, it's desperate, and we don't give you the option to give up, right? It's not really about "is this going to make me live or die or succeed or not?" It's just the option that the world--the zombie apocalypse world--has presented you. You have to artificially map them to "are one of these choices better than the other?" That's the mantra of the game. There are no good choices, it's just what's available to you at the moment.

Rodkin: One of the designers on the game, Chuck Jordan, he was on the early story a lot, and he's the one who came up with St. John and the storyline in episode two. The things that he's always said about this game that I think is incredibly interesting is what makes a lot of video games interesting to play is that you input things to the keyboard, you poke at them, and then watch as the screen as interesting things happen inside of the game, and it gives you something back. Whereas The Walking Dead, that equation is kind of reversed. The game has very simple inputs for you as a player, but it outputs things into your brain that then bounce around and make you do complicated and weird things. It's an odd thing to think about. Games.

Bruner: Sometimes I think we invented a new genre called "head games."

GB: It seemed fairly obvious this episode there would be a moment where you have a moral surrogate for reflection on what you've done. I was waiting to see how that moment was handled, whether through a series of flashbacks in a very passive way or something else. How did you arrive at a huge story twist with a character teased throughout the whole series?

Rodkin: I think it was a thing that we nebulously kind of thought would be cool, but the place I remember us really concretely thinking about it was still before the first episode came out. We were doing really early discussions for episode three, and we were talking about how aggressively Lee's past should come out with Lily. For quite a while there, we actually said "it actually doesn't matter whether his past comes out with Lily," and this is where we realized "oh, because Clementine has been talking to that guy on the walkie talkie, so he knows all about you! So he is going to totally eff you up at end of the game, no matter what." And we all said "Oh, man, awesome! Sweet"! And, then, of course, when episode three came around, we realized we'd be stupid to not talk about Lee's past in that episode. It was a thing we talked about early on, then kind of forgot about a little bit, and then we reminded ourselves and made sure to focus on it pretty hard right before episode one came out. It had been hidden in the story a while.

Vanaman: I think somebody brought up the idea of [how] your actions from a different perspective can look completely different. And that's not an incredibly unique idea, and especially not an incredibly unique thing for a story to say, but that was just a seed of a stranger's perspective. You don't look like the greatest person. That's just more of a rumination on being a human being. I think everybody walks around feeling relatively justified. You feel like you're outputting a certain person, but you're probably outputting something very different than you think. That went on the shelf early, but it I gotta tell you, I was really lucky to work on this game because of the minds that were on it, and the ideas came out so early about the whole season. We had a tremendous amount of confidence early on in those big pillars, like the stranger and Lee dying in the end.

Rodkin: That scene in the hotel room and that scene in the jewelry store are things that we've been excited about forever and ever.

Vanaman: For over a year.

Rodkin: Yeah. Knowing that the game was going to end there was a thing that kept a lot of us really dorkily excited about our own game for a really long time, and I think it's very easy to lose sight of the end of your story. You can be tempted to start changing with it and screwing with it as you go. But everybody on the team was really stoked about the walkie talkie guy showing up, and totally, totally screwing you over at the end.

Vanaman: I also attribute a lot of that to the episodic format. You make those decisions, and you lay that track in episodes one and two. You can't patch the game, you can't say "surprise, everybody, we're actually gonna not do the things that we seeded in one and two!" If we withheld all those episodes and got to the end of episode five and wussed out, we could kind of go back and we could look at chapter one or chapter two and adjust things…

Rodkin: Well, there was that backup plan there the villain was Larry's ghost.

Vanaman: That's true. [laughs]

GB: What's interesting about that conversation is that not only is an outside conservation commenting on what you did and providing a perspective you can't have as the person who came up with internal justifications for those actions, but you're given a chance to respond. Essentially, you could mentally wash away the reasons you did do that. Your reflection on that is really complicated, given that it's much later than when you made those decisions.

Vanaman: Yeah. You can see the previous answer about what you like to do as a person, I think people do that. Also, it was really important--I remember sitting down to look at it--in a room, telling everyone, "I really want the player to say they're sorry and regret their decision if they do." That was spawned by a really crunchy other game desire, where so many times I'll screw up in a game, I'll fire off three rounds into a crowded area, and I just wish there was an "I'm sorry" button. I'M SORRY! NO BIG DEAL! And then everybody would calm down.

Rodkin: In GTA, when you're walking down a city street, and you accidentally press a punch button and then a guy is like "what! what!" You're in fight mode, and "ahhh! Ahhh! Ahhhhhhh!" [laughs] I think in The Walking Dead, I read forums and emails and Twitter and stuff really obsessively, and you can see the players say to themselves "oh, man, why did I help drop that salt lick on Larry's head? Holy shit!" So to let them have the game give them the opportunity to say "I would not have done that again if I could go back" without actually forcing them to go back and replay it, I think that's very cool.

We're into the idea of being able to own one solid playthrough if they want, and have that be their story. There are some people who really like actually gaming the game and actually going back and rewinding and stuff, but for players for whom their one play-through is their canon Lee story, they've established what this Walking Dead universe is for themselves. Being able to look back within the game and express regret is, especially for people who've been living with it for six months, something that I was really, really happy to see make it into the game.

GB: Was it always the intention to portray the stranger as crazy and deranged? You can't have too much sympathy for his motives.

Rodkin: I think we hoped that, at least at the beginning of the conversation, you would look at him and go "oh, man." I think there are some people who--I hope there are people who--got into that conversation with the stranger, and the beginning was just them thinking "holy shit, I'm terrible."

Vanaman: He offers, "I'm taking her [Clementine] with me, it's gonna be okay." And you can say "yeah, that's a good idea."

Rodkin: I don't know how many people said that, I don't think we've looked.

Vanaman: We should go look that up.

Bruner: Casting the stranger was a really difficult problem, and we actually didn't find the right actor for him until the very last minute because he's such a subtle character. He needs to be somewhere between sad, disturbed, deranged but still obviously a danger. It was really hard to find somebody who didn't come off as just completely batshit crazy. Deranged but still sympathetic.

Rodkin: We half-joked about [it] because it wouldn't actually work for any reason, but you could imagine an alternate Walking Dead season one where you're playing as this guy, but his life just goes a completely different way, and he falls off a cliff at some point, and ends up with his wife's head in a bowling bag, so something snapped with this guy at some point, but we wanted your first impression of him to be that this is any guy. This could be any person.

Vanaman: You could have written a revenge story, and let you play it.

Bruner: The family in episode two, where you come across their car, that could have easily been Lee and Clem or Kenny and Katjaa. The idea was that he didn't start out as a maniac. The world got to him in a way it didn't get to Lee.

Rodkin: It seemed on-license that in the world of The Walking Dead, there was a story that would eventually turn and say this guy is so broken that he is an irredeemable threat, but we wanted to start it in a place that was a little bit more complicated than that. The ways that these stories work, the way that Kirkman tells his stuff, if you meet that guy, he's gonna have a head in a bowling bag by the end of the thing. You've gotta take it to the place at the beginning that makes you wonder what the hell is going on.

Bruner: He's kind of like alt-zombie.

Rodkin: Alt-zombie?

Bruner: The world didn't turn him into a zombie, it turned him into…The Walking Dead. [laughs]

GB: Cue title card.

Vanaman: Anthony Lamb is the actor who plays the stranger, and that guy…he recorded his audition on his iPhone. [laughs] Sitting in his garage.

Rodkin: Kind of like The Zodiac Killer. [laughs]

Vanaman: He was just one of those happy actors who was kind of like "well, I have a newborn baby and I didn't know where to record it, so my wife said…" He was a friend of a friend sort of a guy.

Bruner: We really wanted him, and we couldn't track him down. It was down to the wire.

Vanaman: It was one of those things, and he came up from LA. I gotta tell you, man. The whole way through, we're going "is this going to fall on its face?" In the studio, he was really quiet. His voice was eerily quiet a lot of the time. The engineer was like "this is way too quiet, you can't record this." I was like "JUST DO IT!" [laughs] And then [cinematic artist] Dennis Lenart here put that whole scene together, and he…the amount of restraint that he showed in that scene…I just wanted to kiss him on the mouth after that. [laughs] There's no sound in the room.

Rodkin: It's a testament to our composer that he was excited to not have any music during that scene.

Vanaman: And obviously for this game they decided to move a lot of the sound team--we fully transitioned our sound team in-house, which was a really smart decision by the studio. Our sound guys just make that fight feel like human beings were trying to hurt each other.

Bruner: I think that's one of the things that we've been, over the years, as storytellers, we've been really pushing ourselves to use every device available to use to tell stories. There's words, color, composition, timing, sound to make sure these devices work in concert to tell a great story, and a directorial department that's sitting around focused on various aspects of all that stuff. It really came together really nicely. When we got the player to a moment, and then used every single tool available to us to tell the story there.

Rodkin: We will crap on ourselves in a lot of places, but you can tell that we're really, really dorkily proud of the last few scenes in this episode. We're stoked about them. [pause] I think you probably want to talk about the jewelry store stuff.

GB: Yeah, yeah. It's a moment that you know is coming the entire game. From the first episode, at some point, the game is going to have a moment like this, and to some degree, the entire emotional arc for the player all comes down to this conversation. Knowing that going into it, what the hell was it like to write? I have to imagine you must have gone back-and-forth on it a million times.

Rodkin: Starting off, given that the first interaction you have in this game is to kick out a window of a police car and take your handcuffs off, we hope that players feel like they're on borrowed time for the entirety of this game.

Vanaman: I was worried at the end it'd be too obvious. Of course he's going to die! [laughs]

Rodkin: The first thing [you see] is that you're being driven to sit in a room for the rest of your life, and then you escape. But, spoiler, The Walking Dead is actually a Final Destination sequel. [laughs]

Vanaman: I don't know what to say. Again, it was another tremendous opportunity to put the words down. I'll never be able to quite articulate how awesome it is to just be able to focus on the work, do your job, and know people are going to make it ten million times better than you can imagine. There's no room…you don't have to…[pause] Ugh. It's just that you don't have to worry about that aspect of it. Coming into this, looking a season down, I said "oh, guys, I want to write episodes one and five," and I was fortunate enough to be able to. I was waiting to write that jewelry store scene for a long time. It's been in my head for months and months and months. Everybody supported it, everybody liked it, everybody brought something different to it. The only thing I was really focused on was the dialogue there at the end. It was one of the coolest professional experiences I've ever had.

GB: What did you want players to get out of it? Was there something you were working towards?

Vanaman: I think everybody on the team wants something different, and I think that's amazing, and that's why it's great to make games, and that's why it's great to be at this studio--it's awesome. Everybody feels something different playing it at the studio, and everybody feels something different making it. The goal is not to make the emotional content so narrow that other people can't accept it. I don't really know how to describe it other than that.

Bruner: I think we just wanted people to care.

Vanaman: Yeah.

Bruner: You can see Lee dying at the end, but what you didn't see was how much it could mean.

Vanaman: We all see him dying on screen, but we're all feeling something different, but you don't know if it's going to hit all the themes or not until people play it. You really hope it lands, it sticks. It lands, and people care.

Rodkin: It's a situation where everyone--the directors, the animators, everyone--and I'm saying this and it's the cheesiest, corniest thing in the world and I'm sorry to everyone, but I think that all we set out to do was do right by the story. Literally, down to the last minute, it was just us saying "what needs to be here? Lee is going to die, make it count. Do right by Lee, do right by Clementine." I think that the people making the game don't have the same emotional reaction that the people playing the game do, but we tried to not be cheesy about it, and not be melodramatic about, and not undercut it, and hope the people that are really invested in what's going on, they feel like the ending is deserved and is what they want to see and what they want to experience.

It's weird. Sam & Max season three had this really poignant ending, but it's total joke goofy game. And that was my first experience with that, where I thought--I actually felt really bad when we were ending Sam & Max. I just thought it was a big joke, and then people in the forums said they misted up and cried a little bit when [it was over]. It made you realize that the way people invest in stories, especially in games, is really real, and you've got to believe the people playing the game believe in the characters, and you can't let yourself out of caring, if that makes any sense.

Vanaman: You can punt, especially in today's ecosystem. We could just get a little cynical or get a little fantastic or get a little too cool for school. It's really easy to do that. Everybody who works here is incredibly sincere, and I think that's why it works.

Bruner: There's not a big agenda at the end of the game. It's not like "good triumphs evil!" or "morality play!" It's just the end.

Vanaman: Yeah.

GB: One of the weird, misguided metrics people have used in the past to determine whether games are becoming more meaningful is the idea of whether a game makes you cry. By all accounts, it seems like you succeeded in getting a lot of people to cry, and I'll at least admit you got me as close as a game has managed to do.

Rodkin: We almost broke through the cold heart of Klepek! [laughs]

GB: Jeez. I didn't cry at the beginning of, fuck, what was it? Not Wall-E.

Rodkin: Up? I thought you said "I didn't cry at the beginning of QWOP." [laughs]

GB: I already know that I'm a monster. I weep at the end of the last episode of Lost, so I know there are things that get to me.

Rodkin: Lost made you cry?!

GB: Yes.

Rodkin: No judging, sorry, no judging! [laughs]

GB: There's all sorts of reasons that Lost can make a person cry! But given this weird metric that I don't think is all that meaningful, it's something you guys certainly succeeded with in those final moments. To have achieved that with so many people, what is it like to know that you hit the mark?

Rodkin: I think people crying at the end is the most concrete thing, but…

Vanaman: It's pretty short-hand for people caring.

Rodkin: I think what we're the most proud of is that we put together a game that the audience is responding to from an emotional place, across the board. When the response that people felt with Carly--or in some cases Doug!--that was not a crying moment. But I know from what people have told us [is] that moment took people to a place when playing the game that they hadn't experienced…it's nuts.

Vanaman: They were disappointed because they lost something.

Rodkin: Everyone on the team, and the company as a whole, is really proud of the fact that we put out a game that gets people thinking about it not entirely as a game, but as a story. You respond to it the way you respond to a film or a book. When you're reading a book, you're not thinking about what page I'm on or what font it's set in or whether you have to turn the book upside down. When you're watching a film, you're not necessarily thinking about the projector or anything. When you're playing a game, very often what's really interesting about the game, is that it's entirely about the buttons you're pressing and not what you're feeling. Getting people to suspend their disbelief so that it extends out so that your mind skips over the game controller and the game consoles and goes straight to what you're experience is something we're super proud of.

Bruner: It's really hardcore roleplaying, and not RPG stats of roleplaying.

Rodkin: It's a kind of investment?

Bruner: Yeah. When you're playing The Walking Dead and you're wandering around, it's a little different than when I'm wandering around in Uncharted or something like that. I feel like my avatar isn't a cursor, I feel like I'm Lee and I'm playing The Walking Dead. When I'm exploring a space, I'm doing it as Lee, not as a video game player with an avatar as my tool.

Rodkin: It's a thing that we were really consciously aiming for, and I know, obviously, there are some people for whom it didn't work, but for the people for whom it did, we're really proud and really pleased about that.

Vanaman: I almost feel like a better thing is…a game that makes you cry, I feel like if you'd said "a game that produces empathy" is probably a more broad and a more applicable thing because so many other mediums do that really well. I think games can do it secretly better than almost everything if we just give it a go.

Have you played Cart Life yet?

GB: No, it's on my list of games to play.

Vanaman: Go ahead and log that under games that foster empathy.

Bruner: I think one of the greatest things about The Walking Dead is that when you play, you really do play as Lee. You become someone else, and so many video games try to take the any man that the player can project themselves on to. It's me in the game, the player identity in the game. Whereas you really become Lee. You embody Lee, and his situation and his motivation. It provides a door for the player to really roleplay and become Lee in this world.

Rodkin: Lee is not capable of exerting his will fully over everything in the world.

Bruner: I think the game would suck if it had a character creator mode at the beginning of it. You can try to mold Lee into whatever you wanted, but that's not roleplaying, that's something different.

Rodkin: We did let five people play as themselves in The Walking Dead, but then it turned out they were zombies and got cut in half. [laughs]

GB: It seemed somewhat telegraphed that this was a story about Clementine, and the choices you made were about letting her have a better life. But at the end, when you're given the choice on how to handle Lee, was it always the plan to give players an option?

Vanaman: We talked about that one, in particular, quite a bit. We had this high-falutin' desire where the game would decide.

Rodkin: We knew that Lee was going to get left or shot by Clementine, but how much of that is on the player, how much of that is on Clementine and yourself was a thing that we poked at a lot. Where we landed I'm really happy with. I actually wasn't sold on it at first, but we realized so much of this game was about Lee preparing Clementine for what's out there in the world. It seemed unrealistic and just weird to have Clementine to decide for herself at this point. What would actually happen if you were Clementine? What would actually happen if you were Lee and Clementine in that place? What the story really needed was for this to become the ultimate teaching moment between Lee and Clementine. We let the player choose what to tell Clementine, but then without you being able to choose what happens, Lee always stays back and reflects on why that decision makes sense. He'll bring up the thing that happened with the woman who wanted to commit suicide in the motor inn in episode one or the decision that he made with Larry and the St. John brothers and he'll tell Clementine "you have to do this because, remember back when I did this? This is why you have to carry on with this outlook." The way that [came out], I was really pleased with.

Vanaman: The group consensus that Clementine was [going to listen to you] essentially and do it, and then I really struggled to put that into words. So I went to Jake and said "Jake, I think I'm screwed here, man," and we talked about it a lot. I remember exactly that next morning. If I was Lee and Jake was Clementine, look at that. [laughs] "Jake, wouldn't you do whatever I told you to do?" And he's like "yeah, holy shit!"

Rodkin: I would always kill you.

Vanaman: And then I came in the next morning, and Kevin was the first person I saw, and I said "Kevin, can we talk about this for a second?" Instantly, you were like "yeah, yeah, of course, why weren't we doing that from the beginning?" And then I had all this confidence.

Bruner: When it's a game about choice, teaching Clem and everything you've done to prepare her and the whole world is telling [you] "you've gotta look out for that little girl, it's a big dangerous world." It's challenging this presumption you have any idea you know what you're doing. It seemed like, at the end, it's empowering the player. Everybody's been saying you have no idea, questioning your ability to take care of this girl. Now is the moment where you have to prove yourself, and you can express that anyway you want. It's yours. The game lets you do your right thing.

Rodkin: There's one funny detail that we may as well mention. This is a timed choice, and if you let the timer run out and Lee says nothing, Clementine does decide for herself. If you aren't there for Clementine when she asks you what you should do, she does actually look back at everything that's happened and she'll decide if she wants to do it or not. You can force it on Clementine, but you're a big ass if you do that. I don't think I've seen a playthrough where someone does it. The idea makes me personally feel really horrible, but it's there, if you really wanna poke at Clementine. I don't know how many people actually did it, and even our QA guys were pretty surprised that it happened.

GB: You guys do leave an epilogue in there. I don't know how much you guys want to say about it or how purposely vague you kept it so you weren't writing yourselves into a corner, but how did you want to set up that moment?

Vanaman: For me, it was less about the future and more about reminding you that whatever Clementine's about to do when she sees those figures, it's hopefully directly tied to what you hope she would do.

Rodkin: For me, also, the ending was a concrete piece that you have to have when you're making a game based on The Walking Dead. The Walking Dead is a world that never ends. Robert Kirkman's whole thing was that there's no end to this story, it's not about one person, it's not about one story or one solution to anything. We really wanted to hit home pretty hard [that] Lee Everett's story is done, cut to black--The Walking Dead. But this universe is still going to keep going. Regardless of what you take away from the end, you know concretely that Clementine is still there, and the mark that you've left on the world with your playthrough is still still there, and time is still progressing. The world doesn't close just because Lee's eyes do at the end.

Bruner: Ironically, I really, at first, did not want the epilogue. I wanted it to be...Lee's dead, and that's it.

Rodkin: And we're like, "wait, you're publishing the sequel!"

Bruner: We want to publish the sequel and all that, but I thought it was satisfying, at least in my mind, to cut to black. But these guys came and said "no, it's going to be super cool," and I'm actually really thrilled with how it turned out. I thought the epilogue doesn't necessarily just open the door to what happens next, but that it does remind you the possibilities about how life goes on. It's just a Walking Dead trick--maybe it's not as tragic as it seems! Yes, it probably is.

GB: You said you've taken in the acclaim and then try to move past it, but whether it's The Walking Dead or Fables, how do you internalize this experience and take that forward without it completely wrecking you mentally of "oh, I have to follow-up The Walking Dead!"?

Rodkin: We're mostly excited people are responding to what we're doing, but internally, we're mostly trying to not screw up the things that we think we've screwed up. It sounds suspicious but it's actually entirely optimistic. One of our internal mottos is "suck less." We are beyond thrilled that people have been playing The Walking Dead and liking it the way they have, and for us it's just a motivation to do better. When we look at the game, we're excited about all the things that people are excited about, but we also see nothing but room to improve and opportunities missed that we could take the next time around to do interesting things. We're not going to just turn [Telltale Games] into The Walking Dead re-skin factory because nobody actually wants that, including us.

Bruner: If you look at the history of all the games we've done, every game, we've tried to solve a specific problem, all the way back to the early Sam & Max games. Each series has been trying to be a good console game and a good mass market game or something like that, and a lot of those lessons were learned in a critical mass in Walking Dead. There's still a lot from The Walking Dead that we're going to roll forward with. It's a diligent march to keep making better story games and better character-driven games. We're just going to keep marching forward, and we're really happy that people really got The Walking Dead and what we were doing. But we still feel like there's a lot of room.

Rodkin: We have a lot of momentum right now, but that's obviously not infinite. We have to keep trying to do things that interest players.

Bruner: Fables is a different kind of feeling than Walking Dead. Capturing that is a different problem, and I don't think we can rest on our laurels. It needs to be its own thing that's just as good and just as compelling. The really exciting thing is the notoriety of The Walking Dead certainly is making it so we're having a lot more conversations with a lot of other TV shows and movies and books and things that would be really awesome to make games out of. That's super, super exciting.