Welcome to Off the Clock, my column about the things I do when I’m away from the office. This week I watched...

Games At High Speeds

Awesome Games Done Quick 2016, the latest event in the biannual speedrunning series, ran from January 3 to 10, and I’ve been trying work through bits and pieces of it since then. The week long marathon can be hard to parse, so I figured I’d highlight a few of the runs that I most enjoyed. I want to do that partly just so I can share what I liked with you, but also because it's an excuse to allow me to work through what it is I actually like in a speedrun.

When I first watched a GDQ marathon years ago, it was all so fascinating. I’ve compared all of this to the sort of exhibitions put on display by Olympic athletes before. When I watch the Olympics, even for a sport I’m not particularly interested in, it’s hard not be amazed. Wow, a person can do that? The same was true for GDQ’s speedruns. There was a spectrum of techniques put on display, from simply executing on a game’s “normal” mechanics with supreme efficiency and skill to identifying and utilizing “exploits”--glitches, oversights, and strange mechanical interactions that allow players to do something with a speed that regular players would never obtain. After a lifetime of being knocked into endless pits by pixelated birds, I saw someone beat Ninja Gaiden in 11 minutes. Wow. A person can do that?

But in the intervening time since the first GDQ event I watched, I’ve found myself struggling to remain interested throughout entire marathons. Where once I was amazed by the novelty of speedruns, I’ve become a little more picky. That’s not necessarily a bad thing. It just means that I’m familiar enough with this sort of thing to figure out what exactly it is that I enjoy about the process. So, with that said, here’s what I was taken by in last week’s event.

Kaizo Mario Bros. 3

Not only is speedrunner MitchFlowerPower incredibly skilled, but he and the crew of commentators use this super-hard Super Mario Bros. 3 hack as a jumping off point to issue a fascinating critique of the original SMB3. And y’all know how much I love fascinating critique.

Theirs goes something like this: Kaizo Super Mario Bros. 3 is built in a way that requires the player to skillfully utilize a bunch of mechanics that were present in SMB3, but which were unnecessary. This is the sort of stuff you might be used to seeing if you’ve watched any of the Dan-Patrick feud that’s been running over the last few months. Shell-jumping, double-jumping with kuribo’s shoe, p-switch management, stuff like that. In this way, the commentators suggest that Kaizo Super Mario Bros. 3 better uses Nintendo’s design than Nintendo did.

It’s a simple critique, and one that I’m not sure I fully agree with. I’m a big fan of games with flexible solutions and Kaizo games are anything but flexible. But it’s still a sharp thing to recognize, and it’s being able to communicate this sort of knowledge that makes some speedruns so fun to watch.

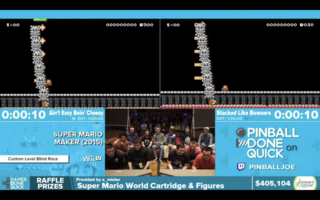

Super Mario Maker Team Relay Race

Yes, more Mario. But hey, we like Super Mario Maker a whole bunch around these parts.

Unlike the majority of AGDQ events, the players in this race were going into levels having never seen them before. So while other runs were about displaying perfect execution of a planned and practiced strategy, this race was about utilizing broader knowledge about Mario to solve difficult challenges. And because it was a team event, it meant doing that together with teammates.

The race was tense and the audience was electric throughout. That was at least in part due to the great commentary, but also because it was very easy to follow the action and understand when one team or the other pulled ahead. It is so often the case with speedruns that there is a real gulf between runner and audience knowledge, leading it hard to determine whether a player is progressing at good pace (more on this later). But in a race with clear checkpoints and win conditions, it's easy to follow along and get caught up in the hype. I'm glad the whole event isn't filled with races, but they're a great addition to the schedule nonetheless.

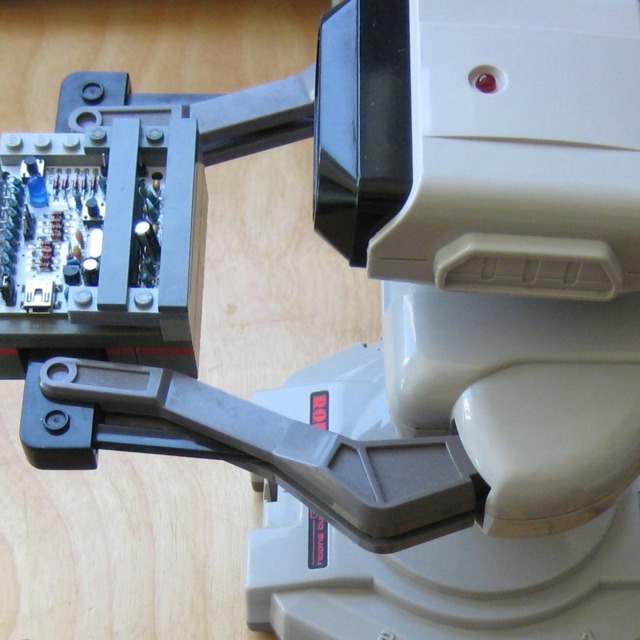

The TASBot Block

This block of speedruns dismisses the idea that Games Done Quick marathons are meant to highlight the manual dexterity of its human performers. Instead, it highlights how mutable games are once the limits of a human operator are taken out of the picture.

The “TAS” in TASbot refers to a tool-assisted speedrun, meaning that the “runners” in these exhibitions are people who programmed a sequence of frame-perfect button presses that allow for results that push beyond natural skill and sometimes even beyond the intended limits of a game’s programming.

From this Mario Kart 64 run (during which TASBot completes an entire cup in the time it would take me to complete a single race) to this Super Mario Bros. 3 run (which uses a sequence of specially timed button presses to reprogram the game’s RAM live on screen), the things these runs display are just incredible. The highlight is definitely the Super Mario World run, in which the runners reveal that they’ve figured out how to add a Mario Maker style level builder to the game--and then plug that creation tool into Twitch chat… which, of course, promptly breaks it in the most amazing way.

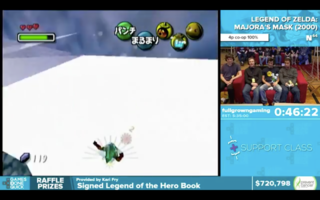

Majora’s Mask 4P Co-Op 100% Run

There’s a point about 43 minutes into this run where the speedrunners--four guys who each play a set chunk of the game--sigh in defeat. “Oh no… he was supposed to backflip over that bomb…” The audience in the room (many of whom are speedrunners themselves) all gasp. But it’s "a prank," the runners say. That death was just one of many intentional deaths necessary to speed through the game in the fastest way possible.

They warn the audience that there will be a degree of unreliability in what will follow: “We’re going to be toying with your emotions basically the whole run.” Link will die now and then, but don’t worry, because that death will be necessary for cutting some corner or for triggering some effect down the line. They add that “there’s probably gonna be a point where it’s gonna be the Boy-Who-Cried-Wolf, where we’re not supposed to die and you guys will think we were supposed to die and, and we’re going to pretend like nothing happened.” I love this so much.

In a room filled with people who also do speedruns, no one (except a very small group which specifically follows the Majora’s Mask scene) will know when a death is intentional or not without without being prompted. That’s how specific and arcane this process is. In this way, speedrunning very different from olympic sports. I’m no figure skater, but I can tell when someone’s fallen down, and I assume that competitors can tell when an opponent has stumbled more subtly or when they ace their routine with complete elegance.

It’s hard for me not to think of speedrunners as scholars. Like academics deciding on a field, speedrunners need to specialize in specific games in order to achieve results (in spite of some commonalities between speedrunning methodology.) As part of this specialization they become experts in the games they run, since they engage with games in a way that the average player never needs to. And I don't mean "expert" the way I might call myself an expert at Knights of the Old Republic II, either.

In a world where games are primarily conceived of as consumer objects, we tend to think of expertise as being knowledge about the game as it’s presented to us by default: You know where Drake Sword is in Dark Souls; I know the secret behind Dragon Age’s Elven gods; she knows each character’s desperation move in Last Blade 2. But these speedrunners have an intimate knowledge that they aren’t supposed to have.

They know something almost metaphysical (but, really, very material) about how these games function as pieces of software and design. Throughout this speedrun, the runners again and again reveal some special knowledge about the way Majora’s Mask is programmed or how some gameplay system actually operates. If this isn’t Software Studies, I don’t know what is.

If you wanna dig through the marathon's videos, you can find them right here.

I’ve also been reading about...

Speedruns... again

About halfway through writing this piece, two of my favorite game critics wrote about their own experiences watching speedruns.

First, Carolyn Petit knocks it out of the park.

It gives life back to video games. Speedrunning reveals to me just how little I know and understand about the games that I thought I knew and understood so well, games like Super Mario Bros. and The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past. There’s an intimacy to it, a breaking past the surface. Speedrunning reveals to me that almost every game is full of secrets; not the kinds of secrets that designers place in games for players to find, but secrets that the designers don’t even know about or intend, secrets that are the game’s own, things borne out of the process of its creation.

Carolyn gets directly at some of the stuff I'm grasping at above, and I highly advise a read.

Second, Alex Piesche expands on the paragraph that I read aloud during last week's Beastcast.

It's a long weekend here in the US, and I'm going to take much of next week off, so there won't be another column until the week of the 24th.

What I do have for you, though, is your weekly question. One of the reasons that speedrunners learn the ins-and-outs of a game is because they love it so much. So, how do you show your love for games that you adore?

Have you learned to speedrun something? Or do you play the same game multiple times (and maybe at a slower speed)? Do you explore your favorite game worlds by creating fan art or fiction? Have you ever used a game you love as inspiration to create your own game? There's a huge range of possible answers here, and I'm looking forward to seeing what you have to say!