We all have goals--some long, some short, and most of them will never happen. Maybe it’s finishing a beloved game that’s fallen into a pile of shame, or shuffling our feet to the gym more than once a year. For Sean Howard, who refuses to call himself a game designer, it’s devising and fleshing out 300 game mechanics and putting them online.

Howard, who most recently contributed dialogue to both of the DeathSpank games, is otherwise a stay-at-home dad who’s hoping to finish reading the Song of Ice and Fire series “before his nerd wife spoils the damn thing."

He also needs to come up with 153 more game mechanics to add to his current pile of 147.

The reason for drawing the line at 300 ideas is simpler than you might think: it’s a big number, a dramatic one, and perhaps a number that would be difficult to top. It's a feat that would be something Howard could call all his own.

“The reason I wanted to do something like that in the first place was because I was sick of people saying that ideas were worthless,” said Howard over email. “It's something I've been hearing for so long, and always at such a deafening volume, that I just wanted to fight back. I wanted to say that, if nothing else, good ideas inspire. They excite you and get the gears moving. That's not worthless. I don't think you can worship the fire without respecting the spark that starts it just a little bit.”

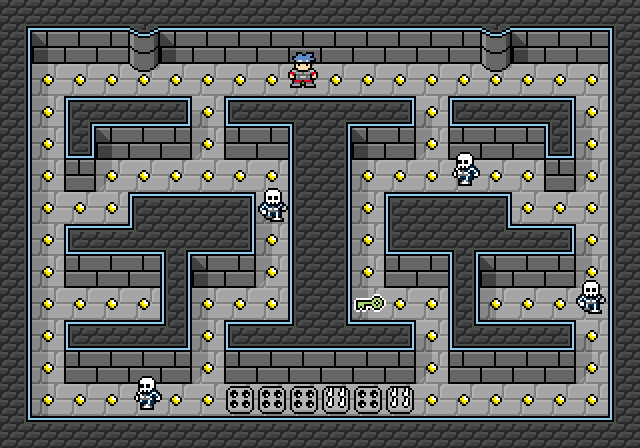

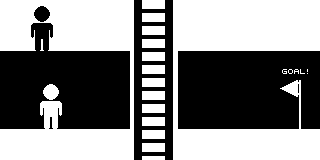

Negative Space, in which he explored the sizable number of gameplay possibilities from being able to flip between black and white spaces, was the first concept published in the experiment, all the way back on May 9, 2007. It's one that he’d actually first started developing farther back in a Usenet post from September 2001.

He goes deeper than a few expository lines about a half-baked concept, instead producing extensive pixel art--a personal expertise--to elaborate on what might otherwise be hard to mentally visualize. Practice within the art of the pixel comes from Howard’s own webcomic called A Modest Destiny, which has lived for years.

All of these ideas used to exist in a notebook, and besides providing a sense of grand ambition and scale, collecting and publishing them online was a way to categorize them for Howard’s own perusal.

“I do feel a need to create at all times,” he said. “It's a clawing need that gets worse if I'm without a project for too long a time.”

How many of us don’t have a similar, gnawing passion? When I go a few days without putting pen to (digital) paper, it hangs heavy. It doesn’t matter what I end up writing, I just need to get a thing out, or else I feel terribly guilty.

“I just want to feel closer to games,” he said. “There's something about them. I'm drawn to them in a way I can't possibly describe. When I was kid, when my future could hold any possibility, I played a game that spoke to me in a way nothing else has. It inspired me and turned on a little light that I've never been able to turn off.”

Outside of contracted dialogue work on DeathSpank, Howard hasn’t been a part of any other game that’s shipped, and the game he worked on that didn’t make it onto shelves, he has no kind words for. It caused him to step back.

“The Three Hundred [Mechanics] is a way for me design games without being a game designer,” he said. “Ask a hundred people how to be a game designer and you'll get a hundred answers. Many of them involve paying your dues. Many involve classes you have to take in college, jobs you have to be employed in, people you have to know, slogans you have to follow, skills you have to have, programs you have to master, and employers you have to flatter.”

One might wonder about the risk of publishing all of your ideas online, and Howard is well aware of the problems. He claims to have seen some ideas taken and turned into commercial products. At one point, he simply asked for credit in such scenarios, but after a few situations turned sour, he waved that away.

“I decided that I would remove that requirement, releasing the ideas fully into the public domain, to end that threat forever,” he said. “It wasn't an easy thing to do. I still feel pride in my ideas. But I've decided that pride should be the reason I share these ideas instead of the reason not to.”

Some ideas are begging to be made, such as Pellet Quest, where Pac-Man gets infused with RPG sensibilities spread across a gigantic, persistent map, and the main character must return to old areas with earned abilities, ala Super Metroid. Or Diorama Designer, in which players create a “screen shot” for a game they’d like to play, and the game procedurally generates a game that makes that scene possible. Or SimMMORPG, in which the player doesn’t manage an ant colony, tower or civilization, but a simulated MMO world. None of these ideas sound easy to make, and there are much simpler ones within Howard’s set of 147 ideas, but they’re exciting to page through and dream.

“I may never earn the right to call myself a game designer,” he concluded, “but the Three Hundred [Mechanics] allows me to feel closer to games than being in the game industry ever did.”

You can continue to follow Howard’s work at www.squidi.net.