In a 7-2 decision announced early today, the U.S. Supreme Court decided to defend the Constitutional rights of games.

The court struck down the California law from 2005 that would have made selling violent video games to minors illegal, essentially placing the medium into the same category as pornography.

The court opinion was written by Justice Scalia. Justices Kennedy, Ginsburg, Sotomayor, Roberts and Kagan agreed. Justices Thomas and Bryer filed dissenting opinions.

"The Act does not comport with the First Amendment," reads the decision. "Video games qualify for First Amendment protection. Like protected books, plays, and movies, they communicate ideas through familiar literary devices and features distinctive to the medium. And the basic principles of freedom of speech...do not vary with a new and different communication medium."

Given that the courts have not blocked violent content in other mediums, California was unable prove why the interactive nature of video games was different than music and movies. The court was also not persuaded by the evidence provided regarding the psychological impact of games. In fact, the court found it curious California would not include other kinds of media under this law.

"Psychological studies purporting to show a connection between exposure to violent video games and harmful effects on children do not prove that such exposure causes minors to act aggressively," said the court. "Any demonstrated effects are both small and indistinguishable from effects produced by other media."

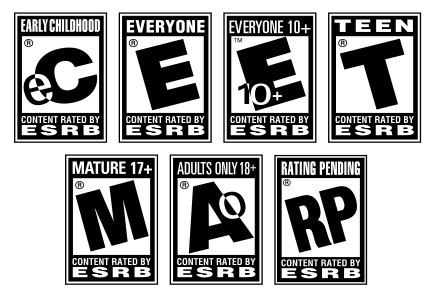

The court agreed with the video game industry that the existing self regulatory board, the Entertainment Software Rattings Board, was doing its job--the government wasn't needed.

"Banning violent games would have necessitated bans elsewhere," argued the court. "California’s argument would fare better if there were a longstanding tradition in this country of specially restricting children’s access to depictions of violence, but there is none. Certainly the books we give children to read--or read to them when they are younger--contain no shortage of gore."

As for the interactive nature of the medium, the court (rather hilariously) pointed to choose-your-own adventure books as evidence that such entertainment already exists.

At points, the court--Scalia, specifically--seems to mock the California law. If video games are such a harm, why would California not go further in preventing society from engaging with them?

== TEASER ==

"The Act is also seriously underinclusive in another respect--and a respect that renders irrelevant the contentions of the concurrence and the dissents that video games are qualitatively different from other portrayals of violence. The California Legislature is perfectly willing to leave this dangerous, mind-altering material in the hands of children so long as one parent (or even an aunt or uncle) says it’s OK. And there are not even any requirements as to how this parental or avuncular relationship is to be verified; apparently the child’s or putative parent’s, aunt’s, or uncle’s say-so suffices. That is not how one addresses a serious social problem."

That ultimately became one half of the court's real problem with California's proposal. If this is a serious social harm, the law doesn't go far enough, as it doesn't restrict other mediums. Combined with the potential infringements on First Amendment rights, it had to be struck down.

"The overbreadth in achieving one goal is not cured by the underbreadth in achieving the other," the court concluded. "Legislation such as this, which is neither fish nor fowl, cannot survive strict scrutiny."

In Justice Alito's concurrence, however, he voiced some disagreement, wondering why the court would be so quick to believe a new medium deserves the same protections as the old ones.

"We should make every effort to understand the new technology," said Alito. We should take into account the possibility that developing technology may have important societal implications that will become apparent only with time. We should not jump to the conclusion that new technology is fundamentally the same as some older thing with which we are familiar. [...] There are reasons to suspect that the experience of playing violent video games just might be very different from reading a book, listening to the radio, or watching a movie or a television show."

In fact, Alito left the door wide open for another challenge.

"I would hold only that the particular law at issue here fails to provide the clear notice that the Constitution requires," said Alito. "I would not squelch legislative efforts to deal with what is perceived by some to be a significant and developing social problem. If differently framed statutes are enacted by the States or by the Federal Government, we can consider the constitutionality of those laws when cases challenging them are presented to us."

While Alito sided with the majority (with a critique), Justice Thomas and Justice Breyer were the two dissenting votes. Thomas argued that, back to the founders, children require special treatment. For several pages, Thomas performs a history lesson of the country's prior views of raising children. Thomas believed the California law hardly infringed upon First Amendment rights.

"All that the law does is prohibit the direct sale or rental of a violent video game to a minor by someone other than the minor’s parent, grandparent, aunt, uncle, or legal guardian," said Thomas. "Where a minor has a parent or guardian, as is usually true, the law does not prevent that minor from obtaining a violent video game with his parent’s or guardian’s help. In the typical case, the only speech affected is speech that bypasses a minor’s parent or guardian. Because such speech does not fall within 'the freedom of speech' as originally understood, California’s law does not ordinarily implicate the First Amendment and is not facially unconstitutional."

Breyer's dissent cites numerous psychological studies favoring that games cause more harm than other media. In the majority opinion, the court rejected California's claims to this.

"This case is ultimately less about censorship than it is about education," wrote Breyer. "Our Constitution cannot succeed in securing the liberties it seeks to protect unless we can raise future generations committed cooperatively to making our system of government work. Education, however, is about choices. Sometimes, children need to learn by making choices for themselves. Other times, choices are made for children--by their parents, by their teachers, and by the people acting democratically through their governments. In my view, the First Amendment does not disable government from helping parents make such a choice here--a choice not to have their children buy extremely violent, interactive video games, which they more than reasonably fear pose only the risk of harm to those children."

For now, however, games are protected speech, an important victory for the medium.

"Reading Dante is unquestionably more cultured and intellectually edifying than playing Mortal Kombat," reads one of the footnotes in the majority opinion. "But these cultural and intellectual differences are not constitutional ones. Crudely violent video games, tawdry TV shows, and cheap novels and magazines are no less forms of speech than The Divine Comedy, and restrictions upon them must survive strict scrutiny."

Amen.

You can read the entire court opinion, including dissents, right over here.