One way to potentially break the ice is to force someone to read the phrase “Virginia Tech Massacre.”

Cards Against Humanity, self-described as “a party game for horrible people,” is an awful version of Apples to Apples. By awful, of couse, I mean amazing, clever, and delightfully insane.

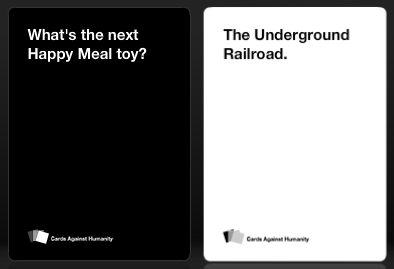

The rules are deceptively simple. Each round, there’s a judge who picks a black card. Everyone responds with white cards. Black cards contain various setups (“Instead of coal, Santa now gives the bad children [blank]”), while white cards are used to fill in the [blank] (“the blood of Christ,” “a bleached asshole,” “poorly-timed Holocaust jokes.”).

The goal isn’t to be accurate, mostly because that’s basically impossible. You want laughter.

At least in my experience, whenever Apples to Apples gets pulled out, it’s a painful wait until someone pulls a blank card and begins scribbling down nightmares. The most vile phrases become part of an otherwise completely innocent game. Cards Against Humanity proposes a version of that game where all of the cards are like that.

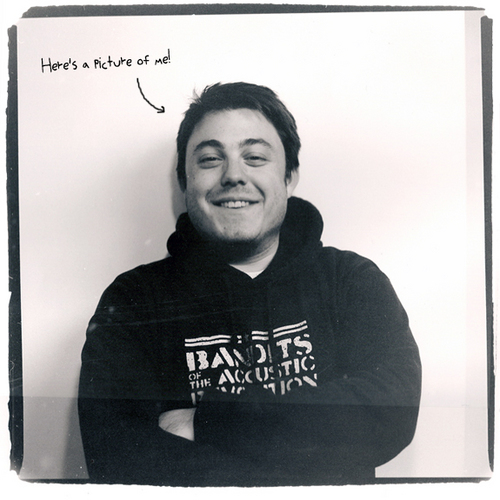

Max Temkin is one of the people you have to thank (blame?) for Cards Against Humanity. Maybe you know him from his other Kickstarters, too: software to drive one of his other pet projects, Human vs. Zombies, and a set of slick-looking philosophy posters.

The Chicago native (and avid deep dish pizza defender) told me the similarities to Apples to Apples were purely coincidental.

“I don’t think the point of Apples to Apples is a comedy game,” he said. “If there’s any conceptual part of Cards Against Humanity that you can say is a good idea, which is already a stretch, it’s that we had the idea that you should have a party game where the point is to be funny in that open model like Apples to Apples.”

Cards Against Humanity is not just Temkin’s baby, though he’s become its public face. The game comes from his core group of friends, people he’s known for years, and started as a New Years Eve distraction. The way Temkin tells it, his group weren’t exactly the kids getting invited to the cool parties you’d heard about in the hallways around high school, so they found other ways to pass time.

“We love structured activities where there are rules and you have cues on how to behave,” he said.

Balderdash, a board game focused on bluffing your way through word definitions, was an early inspiration for Cards Against Humanity. Like Cards Against Humanity, Balderdash has more to do with understanding the psychology of the judge each round, rather than being correct. Being accurate only makes sense when the judge might respect that. Another player might want to be entertained, and you’re forced to change your response appropriately.

An early version of the game didn’t have the white cards. There was a discussion card (i.e. “If you could only eat one food for the rest of your life, what would it be?”), and that’s it. The core of the game was based was pure improvisation, putting the onus of humor and creativity squarely on the player. That worked for Temkin’s tight-knit group of friends, but the moment outsiders came in, the game immediately lost some of its magic.

“They had a really hard time being funny with it,” he said. “They could play honest answers, but they weren’t as good as writing comedy answers that made fun of the other people. We realized that if we’re going to make this game so we can play with other people, we have to put the jokes in for people. “

This when Cards Against Humanity began morphing into a dirty variant of Apples to Apples.

As college friends started asking about how to purchase the game, Temkin’s group put the cards online in PDF form. The decks that existed were hand-crafted. That PDF is still available, but Cards Against Humanity raised $15,570 on Kickstarter (they wanted $4,000), which allowed the game to earn a formal production process. Good luck getting a copy, though--it’s still sold out, and every time the game has become available again, it disappears in hours.

It’s worth the wait, though.

Your first time with Cards Against Humanity, it’s not even about cracking jokes. Every time you flip a card, someone is laughing or groaning. “Win cards” emerge, in which a card is so profoundly offensive or strange, context is irrelevant. The second time, the shock value wears off. “Virginia Tech Massacre” still gets you a little bit, but soon, the card alone isn't enough. That’s when the next layer unfolds, and wordplay skills comes into play.

A real consistency to the jokes embedded on the cards becomes apparent once you’ve seen the full deck, too. Some of Temkin’s friends are still in Chicago, while others have jobs or graduate school elsewhere. Every week, though, they hop onto a Google+ hangout and hash out new cards.

There are no hard and fast rules for the process, and there isn’t a directive to be offensive.

“Offensive cards are fine, there’s no line that we won’t cross,” he said. “It just has to be funny. If you’re making people uncomfortable, it has to be in service of a great joke. If it’s making them uncomfortable and it’s not funny, if it’s just shocking, it’s not worth it for the game.”

The biggest surprise about the card creation process: all of it happens while they’re stone cold sober. I can’t say the same has been true of the times when we’ve played Cards Against Humanity on camera.

As often as life allows, the next step is to have the group get together to finalize new cards face-to-face. This is where the personality dynamics of each member comes into play. Temkin described the process as a hostage negotiation, as one friend tries to convince the whole group why their card shouldn’t be axed.

There is a logic to it all, too.

Are there too many poop jokes? How about sex jokes? Are more cards related to men needed? The details of balancing are tracked via spreadsheet, even if their importance isn't apparent to people busy laughing at “Expecting a burp and vomiting on the floor.”

Sometimes, though, it doesn’t need a reason to be included, and it doesn’t even have to be clever.

“On our last writing retreat, someone said ‘flying sex snakes,’ which isn’t a thing,” he said. “It’s just some words that someone said, but we laughed for like 15 minutes! We couldn’t identify why were laughing, but it just had to go in the game because it made us laugh so much. It’s not responsible to put that card in the game.”

Temkin wasn’t very specific about the future of Cards Against Humanity (don't expect an iPhone version anytime soon), but the reason was obvious: those steps are taken very slowly. It’s dawning on Temkin that Cards Against Humanity is now a legitimate business. This means he’s renting temporary office space near his apartment in Chicago, and consulting with his friends about where to take the game next.

There will be more cards, of course.

For now, he’s processing the idea being a game designer, and if he even wants the title. Given how many would love the next game from the designers of Cards Against Humanity, his group may not have a choice.