Setting expectations at the door is the most reasonable thing a person could do when walking up the dozen or so plant-riddled steps to enter Jonathan Blow's just-up-the-hill apartment in San Francisco.

Stepping inside, there's not much to take in--no clutter--but maybe he cleaned up for us. It's very, very clean, outside of the obvious flatscreen TV, a sheathed sword hanging about a fireplace (and plenty of additional firewood nearby), and a few stacks of media. I notice an opened copy of Castlevania: Lords of Shadow sitting near the top. Behind the couch Ryan and I are sitting on, there's a minimal amount furniture...except for a gigantic keyboard, naturally.

Blow sat down in a chair next to us, loaded up an early version of his new game, The Witness, and spoke.

"I knew this was going to be a really ambitious project for an indie to try and do, so I didn't want to do it for a while," he said. "I prototyped some other things, but then eventually, I [said] 'yeah, this is the game I really want to make.' So, I started a new company because I have employees now!"

He laughed at the notion of having employees, but it's true; there are two, with more incoming. And even though Blow formed a company to release Braid, he started another company for The Witness, pointing towards the additional legal wrinkles of hiring pople as the primary motivator.

Blow is the brain behind the The Witness' design, but the complexities of creating a 3D video game at the scale fitting his vision required those with expertise beyond his own. He hired a 3D modeler and a 3D engine programmer. Hoping to avoid any personal conflict, he purposely didn't bring on any friends. Even with the new help, he still codes.

In terms of basic design (i.e. puzzles), The Witness is largely finished.

"I feel like now I'm already happy with the game design," he said. "It's a good game. I have a year to tune puzzles. [...] What you guys have played right now is what I finished up about a year ago. I consider it polished for prototype."

Since then, Blow has been tweaking how the player moves, how the interface feels.

Unlike virtually ever other press encounter with a game, Blow did not run us through a demo. He provided a brief introduction for context, warned what parts of the game weren't done (art, sound, story), and left the room. The idea of having him standing over our shoulder as we worked through his own puzzle logic was too stressful. Fortunately, it stressed him out, too.

Ryan attempted to articulate what we played for the next two-and-a-half hours in a preview. If you want a more detailed explanation of what The Witness is from the player perspective, make sure and read that before going forward. Now, we're going to jump ahead to when our brains began to hurt, the moment most people would set the game down for the night.

In essence, The Witness is a first-person adventure with puzzles like Myst--but course corrected.

"I really enjoyed Myst when it came out, but I wasn't a professional game designer at that time," he joked.

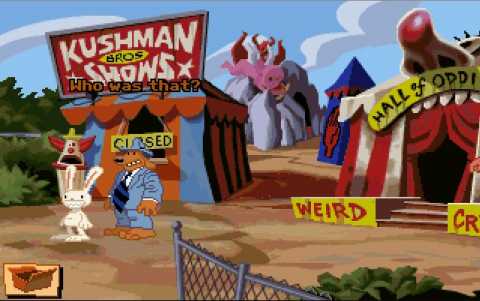

Even without looking at Myst from a designer's perspective, the genre's had issues. What's the designer thinking? As much as I adored Sam & Max Hit the Road and countless other LucasArts adventures, I can't tell you the number of times I'd look up a solution and feel no remorse; there was no way that answer would have ever popped in my head. And don't get me started on the amount of money I may or may not have charged to my parents' phone line calling a 1-800 number for Tex Murphy hints.

There was a logic to the puzzles, sure, but the logic often wasn't apparent until you finally solved it. Some games were worse than others, but even the best of adventure games fell into the trap on occasion.

"In Myst or whatever," he said, "every frickin' lever looks different, behaves different, you don't know what it does. The gameplay is the 3D version of hunt the pixel. What part of this giant machine on the wall is interactive and what does it do? I tried to filter all that out. Once you filter all that out into an interface that's very clear, 'oh, that's a puzzle, I know that's a puzzle. I know basically what I have to do. I have to go from the beginning spot to the end spot, but there's something I have to know to know which way to go.' Once it's that clear, then you can do a lot of crazy, out of left field stuff."

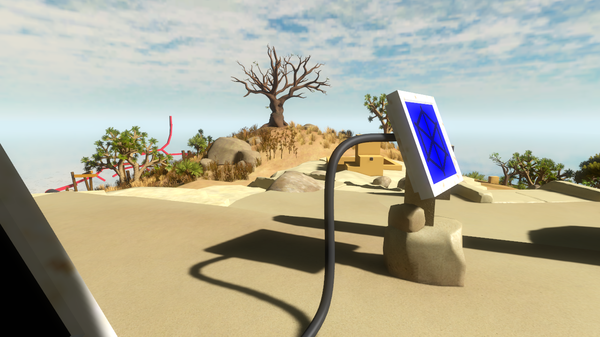

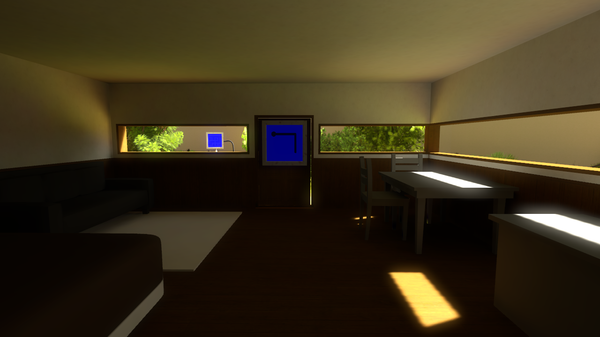

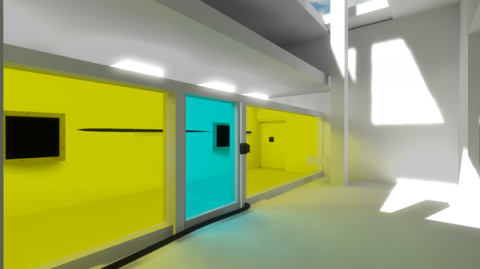

In The Witness, the puzzles are front, center and clearly puzzles. They're all on clearly labeled monitors.

In addition to tackling puzzle games, Blow grumbled over the effect focus testing has had on video games. His ultimate struggle, it seems, is fine tuning the concept of difficulty in a world where challenge isn't really mainstream anymore.

"I think of this being around the time Tomb Raider came out and where, somehow, a puzzle became figure out what lever to pull and then the door opens," he said. "What I've been trying to do with this, and also with Braid, is how can I get real puzzles into a game without fucking the game [up] in the old style [like Myst]? You don't prevent the player from finishing."

The Witness is as much like Braid as it is different, but what the two share in common is the sense of accomplishment when a particularly evil puzzle is solved, the mixed feelings of frustration and wonder when the solution, which seemed so distant just moments ago, becomes painfully obvious. It was there all along, you just hadn't looked at it just right. To explain those moments is to spoil what made Braid, and what may make The Witness, special experiences.

In Braid, however, there was a sense of guilt when you left a puzzle and moved on. You had given up, even if you had every intention of coming back. Leaving a screen has a certain finality to it, which Blow's attempted to solve in The Witness through the 3D environment. There are segments of puzzles across the island, each with its own particular ruleset, but if you get stumped, just walk away. There's no loading screen, nothing. If the solution magically comes to you later, just walk back over.

"It's an open world, you can do whatever you want, but when you get to a certain area, it's linear," said Blow. "You get a feeling of progress. If it was just a bunch of puzzles out in the middle of a flat plain it's like 'okay, I did that, but I don't know why or what's going on.' This is adding just enough context."

The Witness already looks pretty great, even in its visually primitive form. Over the next year or so, Blow will be hitting the game with a "production stick" to transform it. He's working with architects to create the buildings, and developed a whole mythology to the island simply to inform its look.

There's a reason these houses, castles and other objects are here, even if the game never says why.

"The shape of the island right now is just what happened as I was designing the game, like 'oh, the castle should be up high or whatever' but it's not planned," he explained. "What we want to do is invest it with another layer of reality by making it real geology. If there's a ridge here, it happened because of some geological event."

Someone put those puzzles there, too.

Blow was eager to tell us more about the island's secrets, but we actually stopped him from saying too much more. There's only so much he could say, anyway, as the story is still being sketched out. There were some portable radios scattered throughout the island to be discovered, but the writing and voices were all temporary. Everything could change before release.

We'll all know how it turns out in a year or so, when Blow thinks the game will be ready for release.

"What I would have told people was the worst thing about adventure games, you can actually make good...somehow," he said.