The Collected Mother 3

By _nandrews 3 Comments

Originally posted at Nintendo World Report

A Letter to You, Honey

Mother 3 occupies a warm, precedential place in both my gaming and personal lives. We found each other under circumstances that, peculiar as they seemed at the time, could not have been better in retrospect, and it was an igniting force for new experiences and discoveries during what was kind of a turning point in my life.

It was also — and still is — a game I could feel comfortable in. I find more authenticity and genuine resonance in Mother 3 than in any other role-playing game I’ve ever delved into. Part of this, I’ll posit, comes from the interplay between the dichotomous tones of the Mother series: On one hand, it presents a figuratively colorful world, full of vibrant characters and inviting eccentricities. Charming, easy on the eyes, and memorably playful. However, it also addresses the various issues contained within its narrative with a maturity I’ve yet to see matched by its peers. When something bracingly saddening happens, it isn’t glossed over by a veneer of banal RPG expository dialogue, and, just as importantly, it isn’t overly dramatized.

Chapter 1 presents a series of events that exemplify this sentiment. Tragedy strikes — several times, in fact, each one eclipsing the last — and, lo and behold, the characters don’t address one another as if they’re preset cogs in a machine of template emotions. What’s said among them amounts to a retraction from the overblown hysterics of typical game conversations— self-aware, for sure, but constantly insightful and poignant, and often accompanied by scenes of contemplative silence.

The two tones work not in spite of each other, but because of. The heavier content is meaningful because of the lighter side the game displays, and vice versa — a trend which holds fast through the entirety of the game.

Chapter 1, though straightforward and introductory, sets the game’s tonal groundwork in a quiet, minimalist manner I inherently appreciate. Two contributing qualities in this regard: the soundtrack — which may be my favorite of any game — and the magnificent fan translation. The former is an eclectic array of tracks crafted to complement every mood presented, and the latter…well, I wouldn’t be here without the latter.

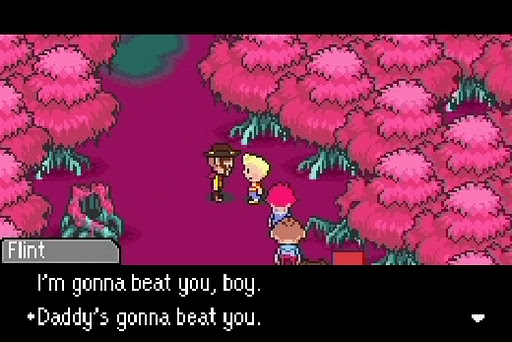

Subsequently, the events of Chapter 1 are among the heaviest of the game. Love, fear, death, anger, and sorrow — in that order — come into play in measured succession. Each emotion is given room to linger and breath in its respective scene, to be taken in with the intended intensity and thought, and to do more than just exist to move the story forward. Flint, the chapter’s main character and a respected father figure, is thoroughly and visibly broken down over the course of the game’s first hour. Watching this strong, stoic man — someone I found myself relating to on some personal levels — fall to his knees, beat the ground in a black, mournful fury and lash out at others upon learning his wife is dead tore me up inside, and injected a new perspective into my still-forming opinion…

Thieves of Justice

…which was done absolutely no favors by the abrupt shift in tone emanating breezily from Chapter 2. What was it I was intended to draw out of this seemingly incongruous portrait of a crusty thief and his quiet, supposed dolt of a son, fresh out of the innocence-obscuring blows of the preceding chapter?

Another look at a family, it turned out — layered in levity, and nearly undone just the same.

Wess and Duster hardly represent an archetypal family unit. There’s a family of five’s worth of bickering and contention between them, but most of it rockets from the elder’s mouth before coming to a condescending smack on the shoulders of his son. The dynamic between them is built less from moments of recognizing any sort father-son kinship they might share than it is from Wess’s casual, open-handed beratement of Duster as his pupil in the art of thievery.

Wess’s ignorably callous demeanor comes in the name of his trade, the skills of which he attempts to force into his son through a regimen of item retrieval and teasingly dismissive moments of attention. As the chapter progresses, however, there’s noticeable tenderness, relenting, and senile silliness in the minutiae of his words and actions as they pertain to Duster; his caricature slumps from antagonistic loudmouth to grouchy well-wisher with questionable parenting methods.

The stretch encompassing the opening fifteen or so minutes of the chapter cement its status as a side view of the thundering events previously witnessed, though not without its own consequential moments. Duster’s fetch quest in Castle Osohe is as much a training exercise — introducing the momentum-shifting rhythmic element of battles — as it is an opportunity to impart perspective on a number of issues, both present and oncoming. In an indelible sequence of moments, there’s a glimpse of a certain corruption being introduced by an outside party, as well as its blossoming perversion of an idyllic society. At the same time, characters who quietly suffered through the brunt of the previous tragedies get the chance to speak, at least for a moment, honestly and poignantly.

Seeing them on their own, at least temporarily bereft of their protagonist puppet strings, is liberating in its own simple way. For one character, my involvement in his present arch seems to have done some good, and I’m happy to see him off into his independent role. For the other, it’s the only glimpse I’ll likely get before things spiral into event…

Happy Families and Kindhearted Neighbors

…like a body, careening through the air after slipping on a banana peel. A banana peel separated from its contents and tossed carelessly over the shoulder of a man not who he claims to be. A man buffoonish in his appearance, slick in his speech, and subtly menacing in his tone.

What’s in a name?

Salsa the monkey’s communication repertoire consists of forlorn looks and longing gazes; sometimes, it’s hard to distinguish between the two. He’ll often wind up facing out, through the screen — usually after receiving a jolt of electric oppression through the slave collar sitting tight around his neck — wearing a mask of empty emotion.

He takes the pain and the abuse and the threats quietly — being a monkey certainly has something to do with that, but it’s almost more of a silent decision of non-action on his part, a willing of his own being to unenthusiastically drudge through the blunt absurdness of his role in the scheme of an unfortunately capable dimwit.

Capability — seen here in the form of shock collars and monkey extortion — is all it takes it seems, and Fassad manages to wield it well enough as a blunt object to conceive and set in motion a sequence of first-rate bastardry.

Salsa plays the subordinate in turn, forced to obey Fassad’s commands, act the counterpart to his subterfuge, and silently suffer lest his primate friend face whatever true wrath the thug actually possesses. It’s a wonder the control to lead, collect, interact, or fight is given at all — most attempts at individual actions are quickly squashed by Fassad, whose powerful presence in battle actually forces a distinct amount of dependence upon him for survival; even Salsa’s special attacks are mere demeaning performer actions.

As Fassad makes his politician-esque appeal to the simplicities of the people to accept a purchased sense of happiness into their lives — rousing and working the crowd like a snake oil salesman, selling his wares as he shouts out what will amount to self-fulfilling prophecies — Salsa pantomimes the actions set out before him, following with false diligence and allegiance the only path he can follow for the time being…

Things Are Different Now

…but paths change, and this one…this one sure has.The malformed state it’s in can’t even hold the definition of “path” any longer; there’s more dirt under a fingernail than these is here, and more genuine humanity in the face of a porcelain doll.

So what’s with the holdout, the lone exception to the slick new rules of this suburbia on the grow, this bustling epicenter of newfound truths? Only a crybaby, eyes choked with tears that never seem to dry or fade, would quietly discount this progress.

Only a crybaby.

A crybaby. Still in a crybaby’s room—a sparsely furnished room of wood in a sparsely furnished house of the same—but compelled and willing to venture back out.

It’s a bracingly bright reentry into Tazmily. Three years have passed, and the village is…paved. Modern. Built up with concrete and stone and the happiness peddled by a false ideologue behind a trustworthy mustache. It’s a bracing contrast, as well: Lucas’s room is a bastion of comfort and immortalized normalcy, as the town used to be. Even it is not untouched by palpable change, though, however subtle. It’s a deep, unspoken wrenching of the heart through a memory, in this case, facilitated by a length of reflective glass and a moment of remembrance.

Regardless of the subconscious contradistinguishing going on in my own mind as Lucas makes his way about the town, this is a bit of a mournfully monumental occasion.

I am finally—though expectedly—this character, and I’m nearly overburdened by an awkward feeling of knowing more than I should. I’ve watched this boy—going on hours, now—watched his life be ripped and rent asunder, watched him spill tears in his most darkest, most vulnerable moments as a human being—and now, now I’m supposed to move in beside him, take the yoke , and shoulder on, on his behalf.

What right do I have?

- - -

In town, everyone treats Lucas as a relic of sorts, an outsider unaccustomed to the changes of time and the benefits of technology, currency, and status. Flint receives the same billing; his expeditions in the mountains, searching ceaselessly for his missing boy, Claus, are met with the equivalent of a shaken head, a clucked tongue, and a semi-sincere “That’s too bad.” The simple folks must exist on the outskirts of society, and, once they’re of age, the damp, moldy husk of the retirement home on the hill. It’s a sad and off-putting state of affairs, especially when placed in contrast with the homely, tight-knit fabric the town used to be. Now, it’s a cheap designer rag, formed to be expended and re-bought ad nauseam. Keep the people “happy.” Keep them weak-minded. Keep them docile.

The Happy Boxes, which have clearly succeeded in their intended purpose, have blossomed into antennas, picket fences, and little mass-manufactured suburban homes, filled with commercial furniture and appliances and people. They keep their homes laden with the superficial, not knowing why and not wondering. The consumerist veneer is dense.

The new mood is laced with a lining of misanthropy for the stupid few who question or defy; the jail, which was never an active facility, if it even existed prior, bustles with guards.

People work in factories. Children work in factories.

The simple, winding paths have warped into twisting veins of concrete, buffered by more.

- - -

Wess might be the only one left convinced of the evil creeping in. He’s been alone for three years, bereft the the moron he loved dearly.

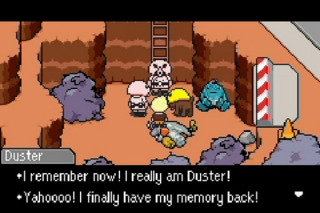

The case of tracking down Duster seems simple enough, what with the unconcealed specificity of the information on his whereabouts. The twisty issue arrives when it turns out Duster doesn’t exist anymore, at least in his own mind. Thanks to a water-induced bought of amnesia, a confused Duster is now Lucky, bewigged bassist for Club Titiboo-favorite DCMC.

Tearing him away from this life—a life where he’s not a moron to anyone, just a valued friend and a capable musician—is an action as unfair and unenjoyable as any in the game, even if he walks through it with nobility and grace, moving toward what appears to be a higher purpose.

The tearful song of goodbye bestowed upon him by the forlorn bandmates is pleasant and well-deserved, but doesn’t make it any easier to force him to turn his back on them, and it doesn’t cushion the march toward the increasingly apparent threat…

The Tower of Love and Peace

…a threat rising dozens upon dozens of feet high, towering over what remains of the tree line. Innocuous enough, apart from a skeletal structure of steel beams skirting its base. A bulbous dome of fluorescent yellow adorning the tip. An intensely conspicuous, comically oversized gun spitting death and destruction down upon the noncompliant.

A behemoth of a misnomer.

As far as the known segments of Mother 3 go, this chapter would sit cleanly along the axis of an RPG graph, clinging to the basic peaks and valleys normally associated with that kind of game. Fresh off a flamboyant combination of characters and environments, a full party (a significant first) makes its way through a series of grind-heavy courses, on a fetch quest for a powerful item and en route to combat a powerful evil.

As training course-like as it may be, there’s a freeing catharsis that goes hand-in-hand with tackling enemy after enemy with a host of reunited characters. Duster himself, finally bereft of his amnesia and filled with a mutually shared joy, might’ve encapsulated it best. Nothing can be expected to last, perhaps, but to journey again as this odd and lovable family of misfits, grievers, princesses, and dogs is deeply comforting.

When the moment finally comes to enter the body of the beast, as it does in the form of a foreboding ascent through the spinal cylinder of the tower’s elevator shaft, the energy in the air is literally audible, if not fully palpable. All of the supposed accidents, atrocities, and convenient acts of a higher power seen thus far sprang from the robot-filled heart of the monstrosity, and it’s an unnerving place to be.

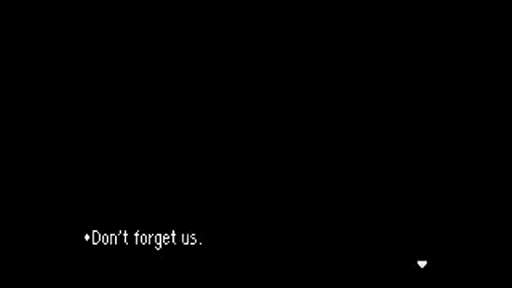

After a satisfying, if predictable encounter atop the tower, and after hints as to the whereabouts of a certain missing brother are disclosed, a shift is made into what is likely my personal favorite moment in a video game, or any other medium, which I’ll gladly leave…

Chapter 6

...unspoiled...

Here Goes No Something

…but such moments of existential peace and beauty are rare and fleeting, and usually capped by the harsh and unfair juxtaposition of reality against the pleasant dream. Like a punctual alarm clock rousing the body from sleep and fighting against a groggy inertia to throw it into motion, though, something inside flips the switch. Focuses the sights. Readies the spirit.

Pulls the needle.

The pertinent question doesn’t concern the size of the dragon slumbering beneath the island, nor how it got there, nor how exactly it’ll desecrate all life it touches, should it come to that.

The question that nags and tugs at the corners of the mind the most is all about the heart within the chest of the one relinquishing needles from their designated insertions; light or dark is easy enough to qualify, but what can—should—be thought of one with a neutral heart? It doesn’t jell—this supposed lack of soul disposition, to put it—with the scenarios of the extreme being bandied about by participants on both sides; it would hardly make sense for one with that kind of composition to enter the fracas at all. But the case is what it is, and this emotionless individual—this adroit, malleable tool of those with a twisted agenda—is the enemy, even if the fact hits home.

The village’s gone to hell in the swiftest of handbaskets. The few who haven’t already expedited themselves bemoan their decisions, and the even fewer who’ve chosen to stay carry on with a pitiful, somber resilience. Flint buries his grief—a quantity to rival all others—by sending himself on expeditions into the mountains, searching doggedly for his long-absent child, before settling at his wife’s grave. Time after time. As a man of great respect and constitution, it’s difficult to see this behavior as anything other than part of a slow drudge into an inescapable depression. It’s enough to wonder: how far behind him could Lucas be?

Arriving at the horrific, clinical, abomination-making reconstruction machine that is the Chimera Lab further cements the profile of insanity being draped over the land, and incites a puzzling disgust for the legions of Pigmask forces—along with a select few other individuals—running and feeding it. The cognitive dissonance between walking through a room of monstrosities, displayed proudly as a series of whimsically pointless scientific victories, and chatting with any one of the soldiers in question—each swaddled in a wishy-washy, shrug-shouldered complicity—is staggering.

After the conclusion of a particularly laborious task—consisting of literally moving water from one hole in the ground to another—and yet another moment of saying goodbye to Salsa the monkey—graced in the end with his true source of happiness, which is more than can be said for many in this story thus far—the real work begins.

The task of going from Magypsy to Magypsy brings about some interesting scenarios. Chief among them is the preparation before and attitude going into death, which each of the whimsical creatures must face as their respective needles are claimed.

Each confronts the situation with admirable good cheer (knowing it’s “that time”) and aplomb, an outlook surprisingly common among many others. It’s really remarkable, even invigorating, how everyone in this world seems to take his or her fate—be it good, mediocre, or life-altering at either extreme—with a contemplative bemusement and an emotionally articulate response, often in the form of humor and good grace.

And then there’s the sober honesty of a momentary encounter with an ordinary man. An enemy, yes, but…a man.

After coursing through the belly of a volcano—and conversing with a hovering robot, interpreting the smooth-jazz rantings of a modified mad man—and an encouraging trip through the appropriately named Saturn Valley, the game rounds a strange, profound bend.

A bed of harmless-looking remote-island mushrooms paves the way for what can only be described as a chemically facilitated odyssey down into the deepest, darkest regresses of the psyche. It starts in a quasi-humourous fashion, with mailboxes containing a series of sardonic comments and concepts, but over the course of a few minutes segues into a stream of character encounters. These faux familiars are dark specters, channeling the negative thoughts and fears and unspoken emotions of aggression and worry and anguish of the main characters, tearing at the weaknesses and scars of the heart in some extremely disturbing, thought provoking ways…

The Ideal Story

…but we’re stronger now, and we know it’s not true, and we can take it. We can reject the ideals and the fear and the manipulation, stop the process, and set everything straight again.

Us.

Together.

New Pork City, to borrow the phrasing of Ned Flanders, is designed to “inflame the senses.”

It’s a bustling social playground, drawing in the refugees of the old towns and the simple ways. With a host of attractions, and amenities, it has everything, but none of it is for you. It’s the one-way trap of a powerful and borderline-nihilistic man-child, a sardonic puppet master hell-bent on feeding his strings through the lives of everything and everyone he can, if only for another temporary helping of amusement.

It’s naturally repulsive, his urge to control and manipulate, but is it unique? The words of Leder’s story—a tell-all tale of a people, sailing away from the end of all things, deciding to wipe their own memories and act out a predetermined structure of existence in the hopes of creating a better life—posit that it might not be. In a situation where everyone’s role is already specifically fabricated to ensure stability, how many degrees of separation are there between that and a total dictatorship?

Irrespective of semantics and intent, action must still be taken. The transition from the close, personal sorrow of a group of individuals to their subsequent abstraction into pawns on a board game of possible catastrophe and potential absolution—the weak boy now tasked with carrying all, most specifically—is nearly complete at this point. The collective fear and uncertainty shared by the close group of friends is replaced by a sense of imminent duty, or at least closure. The childish games and plain-faced taunting of Porky can’t go on.

And they don’t, if all goes well. A sequence of revelations, battles, and tear-stained moments of finality ultimately concludes in a breathless instance of pause—

—before settling, as it would, into a final chorus of the purest of goodbyes.

Log in to comment