Machinarium, a Humble Breakthrough for Adventure Games

By ahoodedfigure 20 Comments

The Progress of Adventure Games

Adventure games have, for a long time, been in the process of streamlining. I think this comes from the old parser days, where people found it frustrating to have to guess what the designers were thinking. They tried to make things more accessible through point-and-click interfaces, allowing you various verbs to interact with the environment.

When this process gained the pixel-hunt reputation for, if you're stumped, having to mouse over every little area to try to guess what, again, the designers were thinking, the mouse-over icon was born. You can see an example of this in the Axel and Pixel Quicklook on this site, where the cursor will sort of tell you what's background and foreground. The verbs, in a sense, are melded with mousing over a location, to where you no longer need to pick the right verb for solving a puzzle. There are still inventory systems with these, so the verbs and items are still in a sense present, but nowhere near the amount that there used to be in games like those using the SCUMM interface, or the old point-and-click Sierra games.

This next step in simplification has been somewhat of a godsend for players who don't have the time and patience to solve puzzles through trial and error if the solution doesn't come naturally. You still get a thrill from solving the puzzle using your own ingenuity, but you can at least progress if you happen not catch what's necessary to do. The problem comes when the process of solving a puzzle now leads to a diminshed puzzle depth, reducing that rush of happy juice in the brain when you figure things out. You run about, knocking things over, until it all falls into place, scanning the cursor over everything to find out what's pushable and what's just in the background.

I'm of a mind that this is one step too far, or at least a half a step. We can still go about figuring out the puzzle methodically, but the reduction in variables is so much that you can, if you want, do little more than wave your magic cursor over the screen to find the points that really matter.

But, Czech This Out:

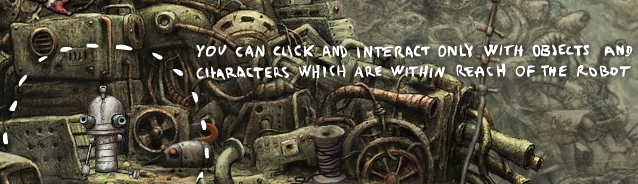

What I discovered while playing the demo for the new game Machinarium, made by the group who brought is the Samarost series, is that they had through clever design found a solution to this problem, while keeping the interactions simple enough not to be too frustrating. With mouse-over contextual icons, adventure games allow the cursor to almost be another character, a semi-sentient puzzle solving creature that automatically knows what a thing is for. It might be too much to ask of us to be able to figure out what an object does and how it should be wielded in order to help solve a puzzle, but sometimes this allows us to be a bit too lazy in actually figuring out how everything fits together. Machinarium solves this dilemma elegantly:

On top of this, your character has the ability to stretch in height, or shorten himself, in order to access areas that are otherwise unreachable at his normal height. Again, experimentation is encouraged, because you have to look at an object and ask yourself if the object is low or high enough to warrant changing the character's shape.

The variables aren't increased substantially, but when you add these layers to the traditional mouse-over, you're forced to do some thinking about where you're going to go next and what you're going to do there. The experimentation must be more intelligent in order to be successful, and that's why I think it's such a breakthrough.

Lessons Learned

Playing the demo made me realize just how lazy the latest iterations of adventure games have made me. I beat a King's Quest or two in my day, as well as the lethal Space Quests and the clever Day of the Tentacle and Fate of Atlantis, so I know how cheap or obscure game designers could be. When I found myself doing the mouse-over thing in Machinarium, and usually not getting anywhere, it became clear what I needed to do was really start observing my environment again, instead of pretending the game was just an interactive painting.

I still didn't solve some of the puzzles, but I found the reason I hadn't was often because I was forgetting to think in the terms the game was telling me to think in. I sometimes forgot that I had to actually be next to an object, rather than be some disembodied cursor spirit. I also found that I often assumed the contextual cursor I saw in a given place was the ONLY possible interaction; again, this was an artifact of this increasing laziness that the self-solving style of puzzles have encouraged. I managed to get past these problems by using the clever two level hint system, but once I figured out what I needed to do, I felt a bit ashamed for using the hints. That's a good sign.

Other Features

The two levels of hints I mentioned let the player get the basic goal of the level, and if that's not enough, a Game & Watch-inspired minigame pops up. If you manage to beat it, you get a generous, step-by-step solution to solving every puzzle in the level. The minigame increases in difficulty every time you try to use it, so it's best to only pull it out when you have to.

You get the usual inventory list of acquired items, some of which you can combine (and they're relatively painless to combine, too, with a minimum of actions needed to do this, unlike some of the older games that would pause to tell you how stupid you were for trying to combine x and y together).

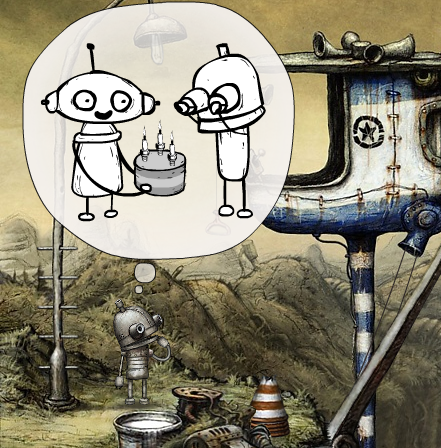

The artwork itself manages to be colorful and bleak at the same time. I like bleak stuff myself, but I tend to like even that to have a sense of color and artistry to it, and Machinarium has that. Just check out their screenshots to see kind of what I mean. The music, by Tomas Dvorak (not sure if he's related to the other guy) has enough quirk to lend the right sense of quiet, mystery, and humor that the robotic main character and the other mechanical inhabitants show with their animations. There are also other touches, like the daydreaming the main character does in addition to his other idle animations, which provide some foreshadowing to things that will be revealed later.

Note that the Steam version doesn't quite give you the soundtrack mp3s as a free bonus, like buying directly from the company does.

I Hope this Is a Sign of Things to Come

What looks like a standard puzzle game, in my opinion at least, is a revolutionary in how it goes about combining the expected adventure elements into something pleasantly challenging and beautiful to see and hear. I hope more developers take this route in the future, rather than trying to simply make things easier or add more distractions to a genre which already has tons of untapped potential. Kudos to Amanita Design!