The Comic Commish: Undertale

By Mento 0 Comments

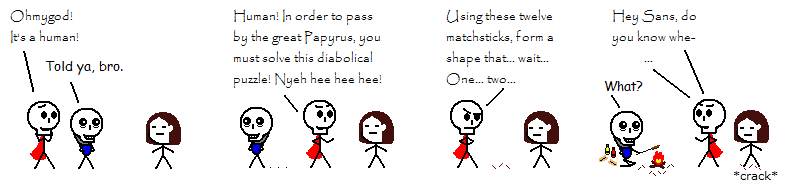

Welcome once again to the Comic Commish: a monthly feature wherein I reward the generosity of those who have bequeathed me video game gifts with pictorial evidence of my appreciation of their presents. Maybe even throw in a joke or two, if I'm feeling up to it.

Previous examples of my paying it forward, albeit to a far lesser degree than the original act of magnanimity, can be seen here: Harvester - Long Live the Queen -Luftrausers - Papers, Please - NiGHTS Into Dreams - Syberia - Freedom Planet - STALKER: Shadow of Chernobyl - Back to the Future: The Game.

Undertale

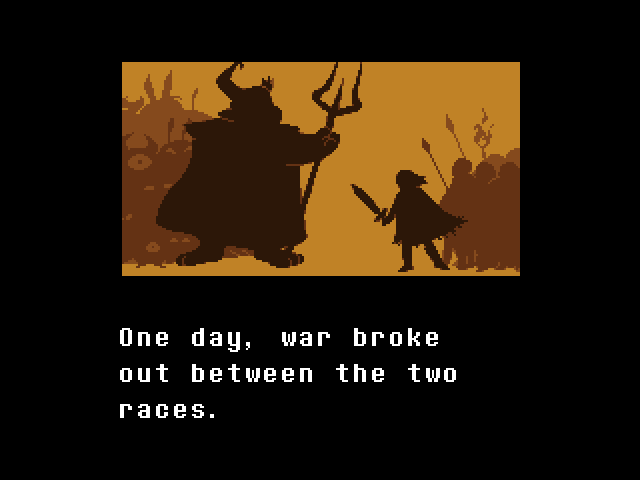

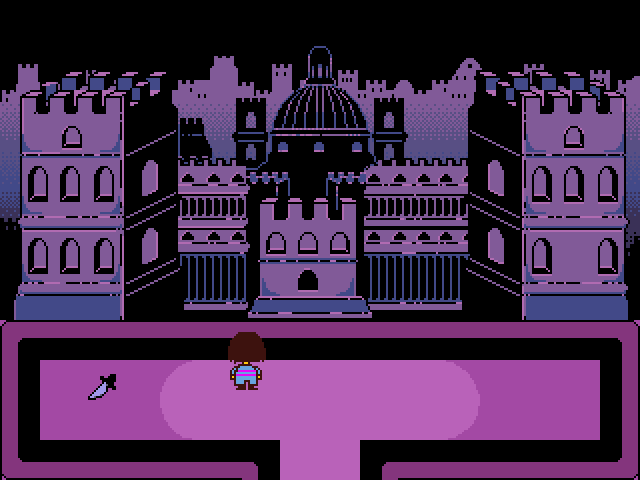

Undertale, this month's Comic Commish subject, is something of a coup for me. I've been wanting to play this one since I first heard of it, as not only is it an RPG heavily inspired by SNES games (which, really, are a dime a dozen) but one that has a subversive streak a mile wide. That can refer to its meta humor, but also to its myriad mechanical and coventional subversions as well. There's also been a few other "deconstructions" of its type that I've been meaning to play, such as Lisa and O.F.F. and, really, EarthBound and Mother 3 as well, which were heavy inspirations to all of the above.

I've played more video games than I've watched movies, seen TV shows or read books, though it's a fairly close race with all four (well, okay, except for books. I'm not as literate as I make myself out to be. Which still isn't very). While I'd be loathe to call myself a "hardcore gamer", since that label has all sorts of unfortunate obsessive and defensive connotations attached to it, it does mean that I've become more selective and less forgiving of tedium in the medium as that total has grown. A game that can genuinely surprise me, or make me laugh, or make me think new thoughts about the way games are made or what they generally ask of us, is not only rare but coveted. Undertale's one of those.

I intend to go into greater detail as part a spoiler-filled "post-script" area beneath the core of this month's Comic Commish. I have a lot I want to say about this game after having completed it, but I also don't want to ruin the game's many surprises for anyone who has yet to reach the game's conclusion (or one of its conclusions, I suppose) themselves.

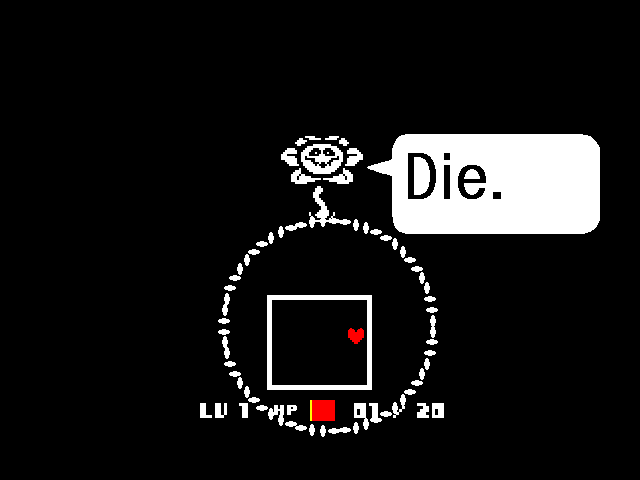

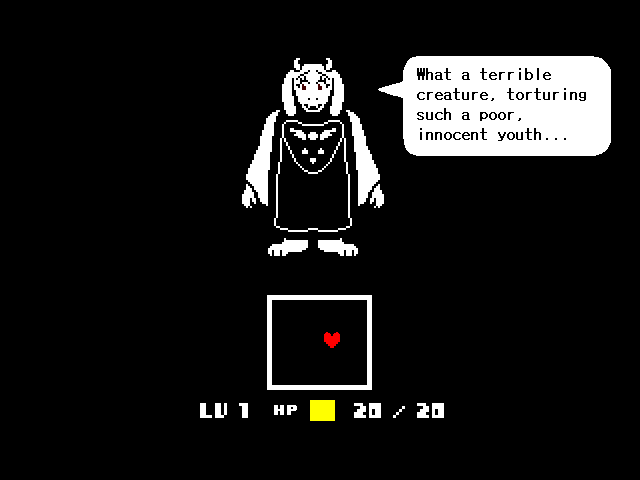

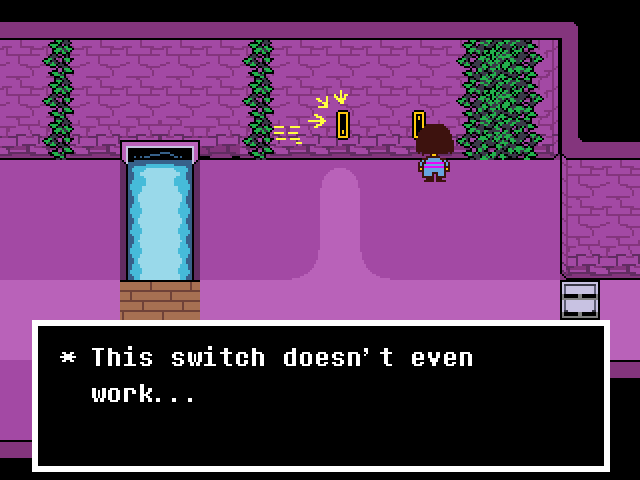

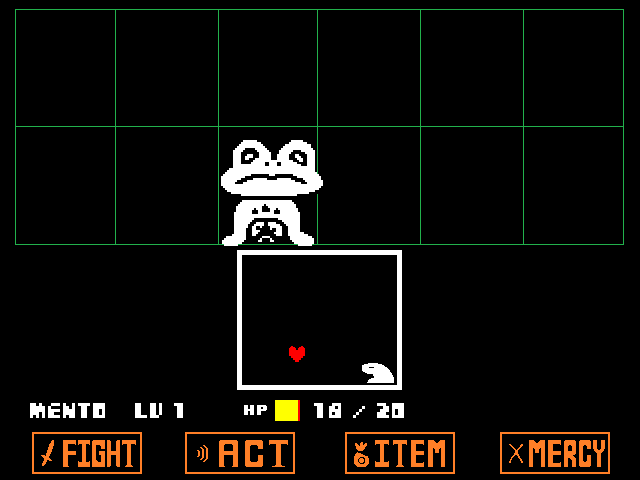

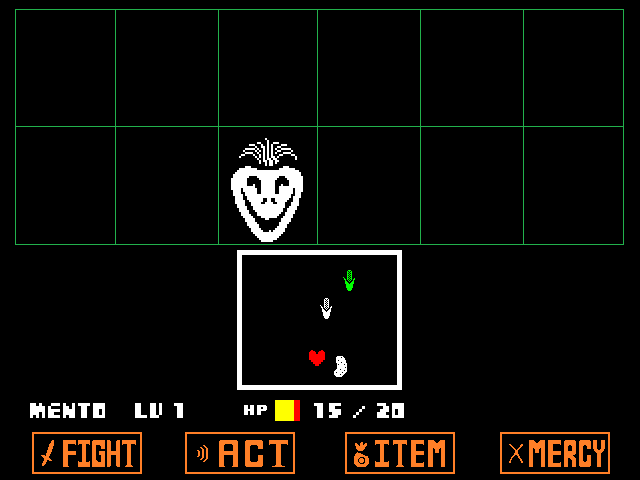

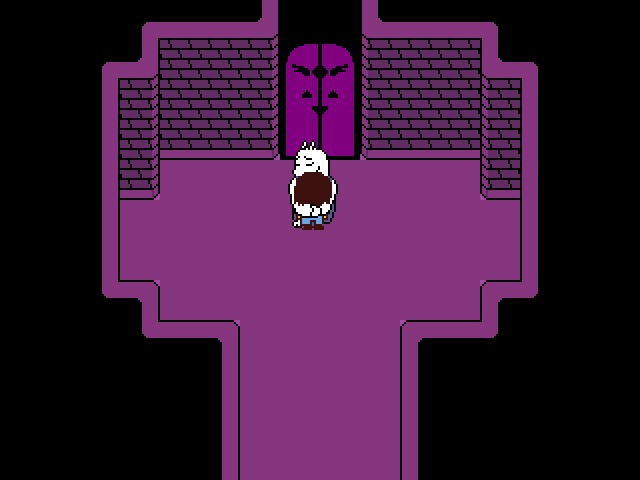

However, for the sake of the Comic Commish itself - the part where I write a bunch of jokey captions underneath screenshots from the game and finish with a comic strip of my own creation - there will be zero spoilers for the game's story or events after the tutorial areas. The intent here is to demonstrate what the game is, hint at its depth and intelligence and maybe reach Sans and Papyrus because Sans and Papyrus are the best.

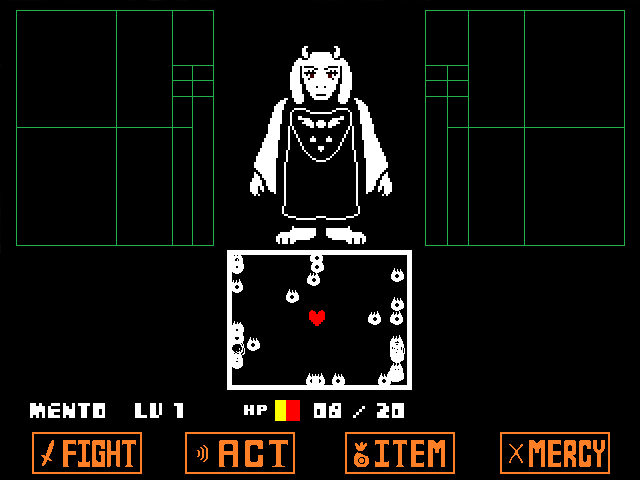

Before I start getting too deep into the game's core, Undertale is a game I'd recommend first and foremost because it respects the player's intelligence. It respects that you're familiar enough with the conventions of the JRPG and of video games in general to constantly flip them on their head in order to surprise you, respects that you'll approach each of its bizarre little scenarios and seek out as much of its hidden jokes and subtle plot details with an open-mind, and it respects that you'll want to find your own way through the monsters and obstacles it's laid out before you, either through compassion or through violence. It respects it enough that it'll alter the playthrough and subsequent playthroughs to reflect your approach, changing how future NPCs interact with you.

Like the Zeboyd JRPG parodies, it can at times stick a little too closely to the hoary conventions it aims to subvert especially early on and during the mid-game, but if you were to play this game you'd be playing it to discover the next classic goof, the next big subversion, the next small character moment or the next diabolically tough boss fight, hooked the whole while. It doesn't pull its punches, either emotionally or in how challenging its combat can become, and it's game that really deserves to be played first-hand rather than via an LP. Possibly multiple times. It's the first game to elicit this sort of response from me since the equally bizarre and wonderful NieR, though Undertale is fortunately not nearly as grindy.

That's all I can really say within this non-spoilerish part. Well, except this:

Part Two: More Words in Spoiler Block City

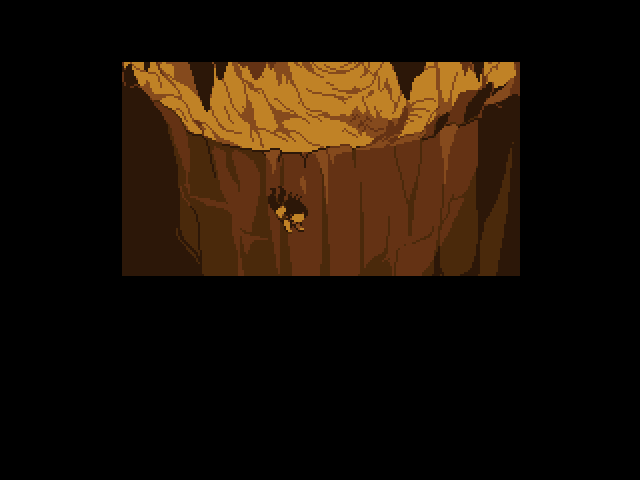

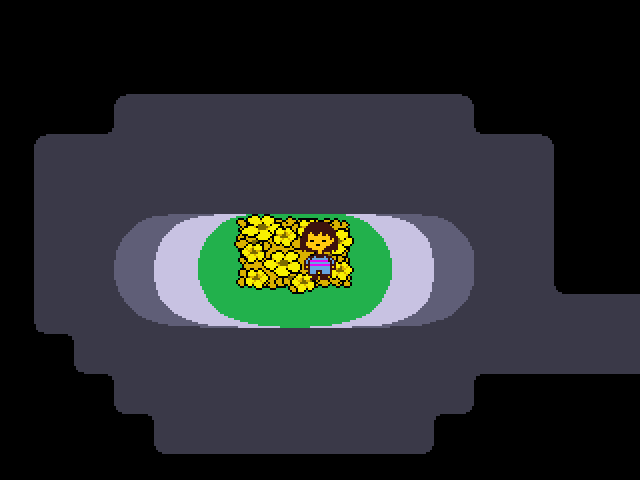

And now - as a special treat for those of you who don't care for spoilers too much and want to know just how endearingly strange this game can be - here's a selection of screenshots I took while playing, utterly devoid of context. Enjoy: