I don’t think I have time anymore to enjoy Borderlands 2, you?

By MMMman 18 Comments

Borderlands had a shiny slipcase; that is why I bought it. I never intended on doing so but the insignificant yet alluring cardboard had me. It also perfectly encapsulates my now far removed opinion of the game. It is fluff, attractive fluff yes, but it will always remain an insubstantial experience, one fuelled by blind and compulsive greed masquerading behind pithy humour and shiny things. An almost perfect metaphor for the video games industry in general? Most likely, but it also proved to be one of my favourite games of 2009, shortly behind Flower, which is obviously the greatest gaming experience of all time.

I don’t consider calling it shallow to be at all a criticism. In terms of shooting mechanics it strikes the almost perfect balance of being challenging and constantly enjoyable. Shooting things in Borderlands is a joy and it stands beside Doom and Quake 2 in my upper echelon purely joy-filled shooting games. That, however, sets a precedent; the core game play of Borderlands is highly reminiscent of that of a by-gone era. Doom was released sixteen years prior, yet the two fundamentally play almost identically. Priority is given to dispatching enemies with little aid from modern cover use, reflexes are rewarded and skilful aiming is a necessity. Shallow, then, is maybe the wrong word to use; pure may be more apt.

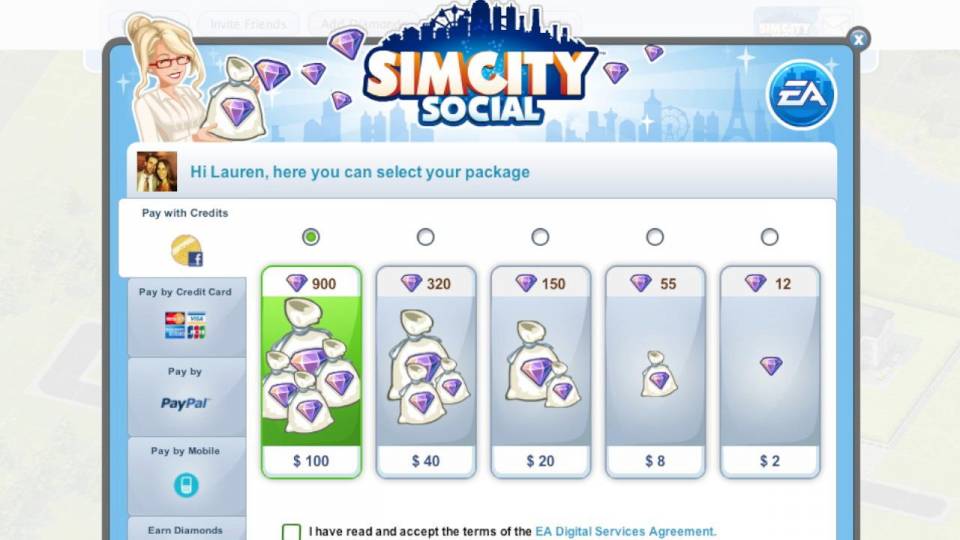

While the shooting in Borderlands had me from the outset it was the, admittedly limited, role-playing aspects which made me persevere. The well-documented lust for a slightly better weapon or shield had me playing daily in an attempt to gather a more substantial arsenal. The random nature of the loot was a source of both compulsion and frustration. One evening I would fully upgrade my equipment only to spend the next week using it ad nauseam, constantly striving for that elusive upgrade. Levelling promised progression that would make everything more productive, though each character bonus was never strong enough to make me unstoppable. Individual level progression began to stretch out across multiple evenings; the more hours I sank into the game the less productive my time was. The second almost perfect metaphor from the game, this time about the curse of addiction? Undoubtedly.

I was truly hooked by Borderlands. I played it solo and exhausted every quest before the finale, fully aware that I would inevitably begin a new game plus upon its completion. That inclination proved misguided; I barely played it again. My will was shattered and I no longer lusted after incremental weapon upgrades. I played the zombie-themed content, though was dismayed by its awkward level design and ended our unhealthy relationship there. Freed from the game’s cruel greed I retired it, along with its attractive facade, to the shelf, thankful that I had escaped its insidious grasp.

After being ‘on the wagon’ ever since I was intrigued by the prospect of a sequel. The Borderlands period of my life contained enough time to allow long games to take their hold. Fallout 3 entertained me for over a hundred hours, though New Vegas stalled at a third of that. Having less time meant I was unable to commit to such protracted games; I don’t like spending my handful of hours a week on a game if it will take me months to fully enjoy. I was a student in 2009 and so had significantly more time to devote to games. Three years later I now have a meaningful job, a long-term partner and a gym membership. All of these things inevitably eat up large swathes of my time, though I still enjoy playing games.

Borderlands 2, then, is everything I can’t appreciate in a game anymore, yet still wish I could. It seems to be very long. I have only played around ten hours so far, though it took up a Saturday and Sunday afternoon; all the game time that I am going to get on a good week. Being long cannot be considered a bad thing of course. It is fantastic for the avid player in that they get a lot of game for their money, especially in a game like this where little is padding. It is entirely centred around shooting lots of things a lot of times and the player knows that upon entry; repetition is the understood game play device after all. I recently finished Darksiders and that surely contains ample amounts of padding. The last third is spent jumping from arena battle to puzzle to repeated boss encounter, something that grinds the game to a halt for about five hours; to its detriment. Borderlands 2 definitely does not force any of that upon the player in such a rigid structure.

Sadly however, things take too long to progress for my predicament. I accomplished ten levels in roughly the same number of hours, the last couple taking over an hour each to garner. The first game held my compulsion bone because I had the time to invest in its progression; I fear I cannot commit to the sequel. While the characters are wittier and the plot that surrounds them more substantial I still do not envisage myself having the time to invest in them. Borderlands was doubtless a great experience throughout the sixty hours I spent with it. It pales in comparison to the memories I have of Flower, however. Journey furthered that experience within an even shorter timeframe; it is just a shame that I can’t work within Borderlands 2’s to enjoy it as much as I did its predecessor.

Log in to comment