On Mass Effect, Part 2: Collaborative storytelling and the end.

By MSG 1 Comments

Yes this post contains spoilers for the Mass Effect series. All titles are fair game. You have been warned.

In part one of this reflection on the Mass Effect series, I retold the games' plot as I saw it: an epic love story set against a galaxy's struggle for survival. It's not a prerequisite for reading part 2, but it does serve as the basis for much of my argument presented here.

Let's cut to the chase: there is no possible ending BioWare could have devised for Mass Effect 3 that would have pleased everyone. The beauty of that series -- something that has been reaffirmed by the outrage surrounding the finale -- is the unique narrative each player builds throughout their 90-hour experience. It's all thanks to collaborative storytelling, with both the player and developer working to build each Shepard's story.

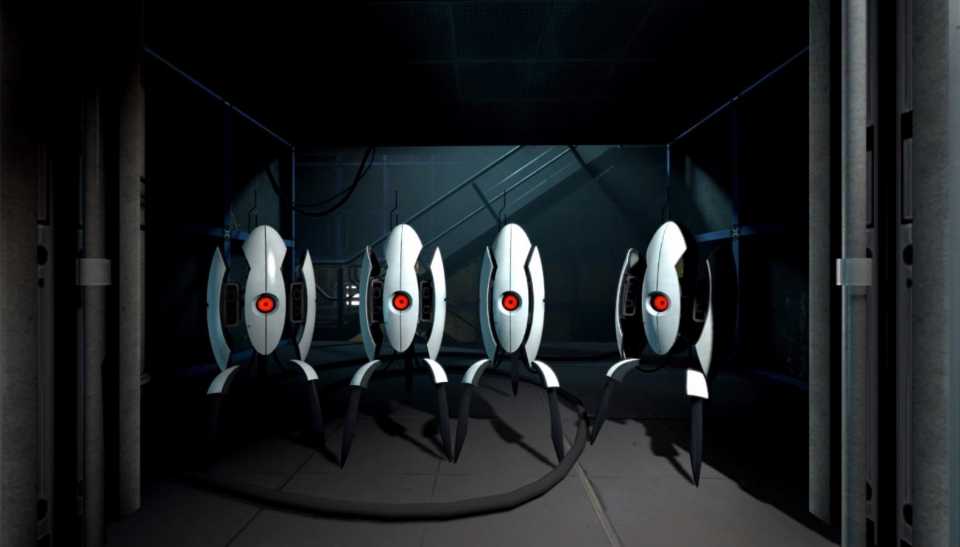

But that's only true to a degree. The greatest trick BioWare ever played was making you think you were somehow writing this story. While there are near infinite combinations of story beats and outcomes across the entirety of the series, each momentary decision is just as trivially presented as the final one: you stand at a crossroad with two, three or maybe, if your lucky, four possible paths. Take your pick.

The feeling of attachment and ownership over your Shepard is birthed out of a totality of your decisions. Your story isn't dictated solely by who you left behind on Virmire or whether or not you cheated on Liara during Mass Effect 2. Those individual moments, while some may be very weighty decisions, are just fractions of your Shepard's identity.

The feeling of attachment and ownership over your Shepard is birthed out of a totality of your decisions. Your story isn't dictated solely by who you left behind on Virmire or whether or not you cheated on Liara during Mass Effect 2. Those individual moments, while some may be very weighty decisions, are just fractions of your Shepard's identity.

But there's a second layer of player driven storytelling that leads to ownership, one that takes place outside the game. Each unique story is informed by which characters, relationships, events and decisions most greatly resonate with the player. This isn't necessarily something we actively decide -- it's based on our own experiences, flaws and aspirations -- but it's at the core of Mass Effect. It's what propels us to save species and romance characters while rejecting others. This is where the player has the most influence on the story. Everything else is just picking and choosing from bits the developers have laid out for you.

Resolution

Herein lies the problem with ending Mass Effect. Because the specifics of each player's story are so unique and personal, (no, not because you chose to cure the genophage, or let the Quarians wipe out the Geth. BioWare was perfectly capable of taking those things into account, and they did) there was really no way to craft a satisfying ending. The writers did what they could: creating an ending that wrapped up, both in narrative and theme, the events and conflicts that were common touchstones for all players, but many of the specifics that you or I might have identified with were left unresolved.

In my version of the story, Shepard is a hopeless romantic driven by his love for Liara. Sure, saving humanity and everybody else would be nice, but he really just wants to put all this war behind him and settle down on some remote planet. Even his final decision, to destroy the reapers, was driven by this (it's the only choice that gives Shepard a chance of surviving the ending).

With this romance being Shepard's main motivation, it's not surprising that I'd have liked a little more closure on that story thread. I just wanted some sort of acknowledgment that Liara, after stepping out of the downed Normandy, was just as concerned with reuniting as Shepard. Hell, I'd even have taken a knowing glance at the stars! (On second thought, that last one would have been pretty good actually; perhaps a bit cliché, but still subtle and effective.) All I got was a hazy memory of Liara as Shepard bumrushed that reactor thingy. Oh, and it wasn't even the first person he remembered. Admiral Anderson before the woman you want to spend the rest of your life with? Really?

My point is, these narratives we construct for our Shepard take control out of the hands of the developer. They've given us the tools -- the characters, the worlds, the choices -- and guided us along the way, but for many players, myself included, they actually did too good a job of masking that guiding hand. When the ending finally rolls along, it comes back and slaps us right in the face. Despite all the narrative control I was given, I didn't write these games and in the end this is just as much BioWare's story as it is mine.

That's the problem with the ending. We've been under the allure of collaborative storytelling for 90 hours, but an ending is definitive. We can bring all we want into it, but we can't mold it to cap the narrative we've built in a meaningful way. This dissonance and the disappointment it has created is understandable, but this is just something we're going to have to come to terms with.

If players really want games this deep, malleable and personally fulfilling, they're going to have to expect some disappointment. As much as it might seem like it, you're not actually writing this story. You can choose how to behave within it as a sort of digital actor and interpret its themes and characters as much as you want, but you're trapped within a playset the developer has built for you.

Collaborative storytelling is a partnership for sure, but one partner did all the work.

Log in to comment