Videogames, satire, and forward progress in Little Inferno

By Stoo99 1 Comments

The point is frequently made surrounding videogames that they rarely attempt to be funny. Although this a sweeping statement and one to be taken with more than a pinch of salt, it’s not incorrect – surveying the comedic landscape in gaming throws up only a handful of significant outliers. There’s Saints Row‘s dedication to floppy pink dildos and sending up all things popular culture. There’s Portal‘s razor sharp, deadpan wit. There’s the knowing, referential humour of Double Fine and Team Meat. But there are very few, if any, games that try their hand at thoughtful, meaningful satire, comedy delivered with purpose and intent. Step up Little Inferno. Across it’s roughly 3-hour length, Little Inferno aims subtle but significant blows in the direction of big game publishers, facebook and casual games, gamers themselves, and the notion of progress in games. Let’s start with that first one.

Little Inferno is pitched as a product of the Tomorrow Corporation, a company whose aesthetic sits somewhere between industrial Victorian, Tim Burton gothic, and Willy Wonka’s chocolate factory. They’re the epitome of the soulless, money-grabbing corporate industry, but blown out to such ridiculous and hilarious extremes that they carefully navigate any lofty political or economic comment. At the same time, their peddling of homogenized, bleakly comic and undoubtedly dangerous “entertainment products” can hardly fail to be recognized for the games industry as it is in 2013, where the commoditization of violence and the proliferation of shooters is creating a wave of derivative, morally ambiguous games which we have no business with but violent consumption. These games are not dangerous because they are violent. They are dangerous because they ask us nothing except to be swallowed whole and taken entirely at face value.

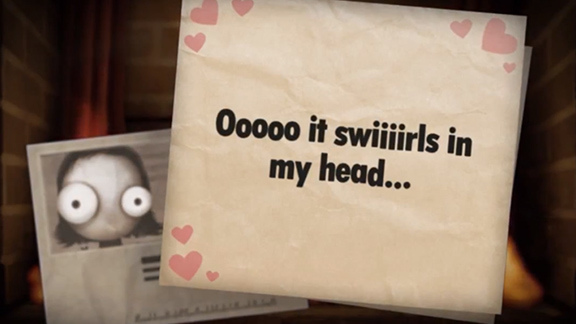

This is exactly the sort of violent, limited interaction which Little Inferno appropriates, with the intention of turning it over and examining it from all sides. The extent of its interactivity is another act of violent consumption, that of burning everything in sight to kindle your fire. But the game constantly draws attention to itself in this regard by contrasting your destructive progress with the quaint, doting letters you receive from your amorous but mentally unstable neighbour, Sugar Plumps. The game is transparent (and surprisingly effective) in its attempts to make you care about this character, but again leaves you with no other option but to burn her letters in your indiscriminate, consuming fire. One particularly memorable moment later in the game provides you with a ‘free hug token’. You can try clicking it, using it, dragging it around. Nope – all you can do, of course, is burn it.

All this empty, rudimentary interactivity, essentially boiling down to clicking on things and then waiting for a bar to refill so you can do it again, is more than a touch reminiscent of the waves of cynical facebook and ‘casual’ games which exploit and monetize the compulsiveness of small, artificially rewarding actions and systems. These games create the illusion of progress or achievement through empty mechanical pleasure (say, clicking on cows in Farmville), asking nothing of the player from a ludic or intellectual standpoint. In this second regard, Little Inferno stands apart. The game is well aware of its own mechanical simplicity, and it turns this fact into an unsettling question when it starts hinting at its own uselessness. One letter late in the game informs you that “Little Inferno Entertainment Fireplace was designed to not matter”. Much like when Hotline Miami asked “do you like hurting people?”, this is a wonderful moment of self-reflection that asks you to think more closely about something you take for granted. And these kind of moments are what’s really important for moving the medium forwards: ones that don’t just do new, interesting things, but also encourage us as players to think about them in new, interesting ways.

In the final stages of the game, Little Inferno turns it’s satirical gaze firmly on its players. As your house burns down and you emerge for the first time into the open air, its perhaps hard not to think of the stereotypical neckbearded gamer, pulling themselves away from a 14-hour World of Warcraft session and stepping into, god forbid, real sunlight. You meet the postman, who comments on your complete and utter obliviousness to his presence. He says that, staring into your fireplace, you hadn’t noticed him even once place his packages next to you. “I’ve just realized I exist”, your character says. You shift uncomfortably in your seat.

Little Inferno seems intent on digging up these kinds of uncomfortable and important questions. Is it really worth your time playing a game if all it provides you with is a cheap, artificial sense of accomplishment? Would your time not be better spent elsewhere? What does it mean to meaningfully interact with a game, anyway? Little Inferno doesn’t provide us with the answers to these questions but, in asking, it reminds us that questioning is the key to forward progress, not just in video games but in any medium. When games can become a two-way conversation rather than an all too familiar monologue, we’ll have taken the most important step forwards yet. And satire, it seems, can be the perfect vehicle for both subtle commentary and self-reflection. So, having said all this, only one question remains…

Do you like clicking things?

Log in to comment