To the Moon writer/director/designer/composer Kan Gao is someone whose talents appear poised to shine in the game industry for a very long time. He is someone who clearly understands what it means to make a video game's story count for something, and he is unafraid to center those stories around challenging subjects that most other game designers assiduously avoid in favor of rote entertainment. The truth is, themes like death, loss, tragedy, and emotional connection can be entertaining--just not in the narrowly uproarious way most game designers tend to focus on. To the Moon is about all of these things, and quite a bit more. It's equally silly and serious, a frivolous adventure that becomes infinitely more meaningful as you trek deeper and deeper into it. And yet, I can't quite call To the Moon a great "game," exactly, because for as much as To the Moon is something you play, its attempts at interactivity are often relegated to the sidelines in favor of pure narrative.

In a sense, it's the opposite of the problem we critics grouse about so often about video games. Gao's talent as a writer and storyteller becomes apparent early on, and his sense of direction is clear and pointed. Even his musical work (at least a portion of which was co-written with veteran composer Laura Shigihara) is strong throughout. But as with all jack-of-all-trades developers, Gao is clearly better at some things than others. His concept for a game design is to borrow liberally from the top-down, 16-bit era RPGs of the early '90s, then remove nearly all the mechanics inherent to that genre in favor of a design that's closer to a classic PC adventure game. You spend a great deal of time pixel hunting through a highly pixelated world, searching for clues that will simply take you to the next story bit. The best thing you can say about it is that it's largely unobtrusive, allowing you to connect with Gao's writing free of frustration.

And that's good, because the writing is superb. In To the Moon, Gao has crafted a sci-fi story as touching and heartbreaking as some of the best films in the genre. But before it becomes that way, it starts out a little goofy, with the introduction of Doctors Eva Rosaline and Neil Watts as they crash their car while trying to avoid a squirrel in the road. These two have been sent to the rural, barely-accessible home of an elderly man known only as Johnny. Their task? To give him the memories he's always wanted. Their job is sort of a reverse take on Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind--where that film's central technology focused on the erasing of memories, To the Moon focuses on the wholesale creation of them. In this case, Johnny's lifelong dream was to go to the moon.

In order to create this new set of idyllic memories, the pair hook themselves up to Johnny's mind and begin traversing backward through Johnny's life, hopping and skipping from memory to memory using connecting objects scattered throughout each memory. Much as Christopher Nolan crafted the mystery of Memento by placing his clues at the chronological end of the story, Gao sets his tale up with numerous peculiar threads dangling enticingly in front of the player. What was the nature of Johnny's relationship with his wife, River, a reclusive and emotionally detached woman with obsessive tendencies? Why does Johnny seem so utterly puzzled when asked about the origins of his desire to visit the moon? Why are there origami rabbits everywhere?

In less capable hands, it would be easy to envision this story spiraling out into some kind of bizarre, mystical nonsense for the sake of ratcheting up the tension in typical video game fashion. By and large, Gao and his crew of collaborators at Freebird Games manage to avoid this. Yes, this is sci-fi, set in the not-too-distant future, thus presenting a wide variety of possible fantastical outcomes that could easily explain everything that's happening away. Instead, Gao trusts his characters to carry this thing through, keeping the focus on Johnny and his memories, while dealing out vital pieces of information that keep this story grounded in a sense of reality, no matter how futuristic it might be.

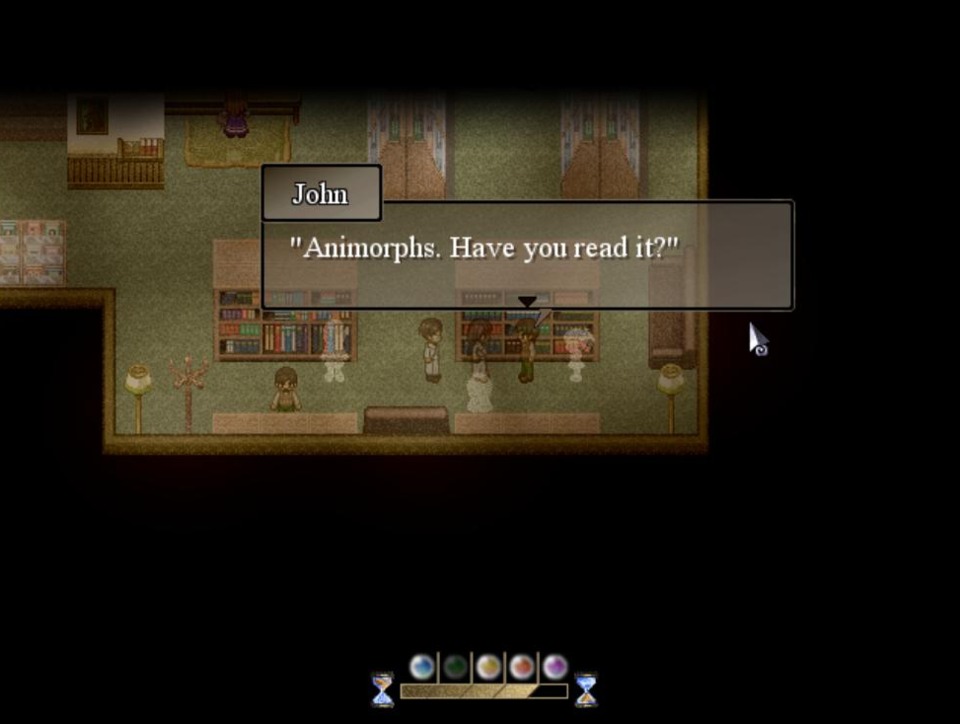

That trust results in a tale filled with characters you legitimately grow to care about. Maybe that sounds odd when you're describing 16-bit looking sprites that largely emote through wide-eyed, startled jumps and periodic shakes of the head, but Gao imbues them with enough humanity to keep you glued to the screen through the whole four hours of To the Moon.

I can already sense the grumbling on the other side of the screen from potential players displeased with that relatively brisk length, but before you get too grouchy about it, a bit of perspective. To the Moon is a $12 game (one currently only available from Freebird Games' website, though it will be on Steam in the near future), and save for a few awkward moments here and there--most egregiously, a late-game shooter sequence that controls about as well as the hunting simulation in the original Oregon Trail--the game hardly wastes a second of that play time. Each moment feels vital to the pacing of the player's discovery, even though you aren't necessarily doing a whole lot to make those discoveries. Again, this game is essentially a pixel hunt, tasking you with clicking around environments to get through dialogue bits and to recognize items you can use to progress to the next stage. There are a few puzzles here and there, but they're rarely challenging and become more than a bit repetitive as the game goes along--thankfully, they disappear before the game's final third.

If there is any issue to be taken with To the Moon outside of gameplay, it's that it periodically has issues finding its tone. As emotionally wrenching as the game can be, Gao counterbalances that dire seriousness with quite a bit of humor, most of which comes from the two doctors constantly butting heads with each other. Their dynamic is very anime, with the headstrong-yet-eternally-curious woman constantly wagging her finger at her lazy manchild of a cohort, and at times, it wears thin. It's especially true when Gao overindulges in memetic Internet humor. Most of those gags are fine, but it pops up a little too often, and sometimes in situations where it's more distracting than it is humorous.

Still, these are the kinds of indiscretions you can forgive in the greater context of an experience as wonderful as To the Moon. This is a game that well represents the enormous potential of a writer/designer on the cusp of delivering something pretty fantastic to our chosen medium. That said potential is not fully realized here is perhaps due to the fact that Freebird Games is, by and large, Gao's baby. The actual number of people credited on this game consists far more of contract content providers than it does actual employees, meaning very few people dedicated themselves wholly to the completion of this project, with Gao chief among them.

As a result, one can easily see why Gao would be so willing to wrap his story in such an age-old style of gaming, given the relatively few restraints it puts on the player. I don't believe that To the Moon's approach of excising gameplay in favor of visual novel-style storytelling is necessarily the answer to the "interactivity vs. narrative" argument developers have struggled with lo these many years, but there are enough flashes of brilliance inside To the Moon's shell to give one the impression that such a breakthrough might be on the horizon. Given more resources, more collaborative experience, and a few more finely crafted tales like To the Moon under his belt, it feels wholly possible that Kan Gao could help bring that breakthrough about someday, perhaps in the not-too-distant future.