Note: The following article contains major spoilers for Ape Out.

"The tiger,

He destroyed his cage,

Yes,

YES,

The tiger is out."

-Nael (Age 6), They're Singing a Song in Their Rocket

If films are something witnessed, then games are something performed; we can define the play in any one game by the nature of our performance on its stage. Most popular performance relies on an entertainer reciting a script; this is true of the large majority of acting, singing, playing of instruments, stand-up comedy, and dance. The creative might put their spin on it, but what the actors say in Hamlet or the notes that make up Kelis's Milkshake generally stay consistent. The mainstream performance of games is, by and large, the reverse. The medium lets us test many tactics and tools to achieve our goals, throws unexpected variables into the mix, supports our discovery, and is open to us engraving playstyles onto it.

Games are rarely our angry drill sergeant, barking orders that we must follow to a tee. They prefer to wave problems in our face and cheer us on as we hack together a solution. Most of those problems are open-ended and pseudo-random because that gives rise to player agency, replayability, and pleasant surprises. In other words, improvisation makes games interesting. So, graphics, systems, and sound effects tend to be far more reactive in games than other media. If you want an example of the differing priorities of games and other artforms, look at the rhythm genre.

Games that hit the top of the charts are usually the kind that let us jet off to wherever in a virtual nation we want or allow us to delicately pick the weights we place on its scales. Yet, the rhythm family demands we press specific buttons or strike exact poses at hard-coded time stamps. Then, and only then, will it reward us. This pickiness is because most music, dance, and other entertainment run on a tight plan, and this format of software links those rigid forms of performance to its play. If the real-world act of performing the Cha Cha Slide or Livin' on a Prayer is identical every time, then play that mimics that dance or that musical performance must also be identical every time. But what if you don't want to be a Just Dance or a Thumper? What if you want your sound to follow your play rather than the other way around?

One impracticality in aligning audio output with tactile input is that we must generally deliver notes in tunes on-beat, but the actions we take in a video game don't conform to a time signature. You can see this in Tetris Effect: an adaptation of the classic block-dropper which sets off musical cues as we plonk down tetrominoes and burn off lines. While Tetris Effect comprises a sonic tour de force, you'll still notice some latency between the pieces slotting into place and the instrumental bursts. That pause is the time between when your tetromino lands and when a sound could be played that would conform to the track's rhythm.

Then there's the issue of harmony. How do you make notes line up with user actions to create coherent tunes when the player behaviour is both notoriously variable and exceedingly unpredictable? Tetris Effect can do it because it has a cosy possibility space. Playgrounds like The Order: 1886 or Tropico offer a whole gamut of options at any one time, and it wouldn't be easy to invent harmonic responses for all of them on the fly.

The fundamental problem here is that you have one style of performance that is reliant on recitation, another that turns on improvisation, and you're trying to mash the two together. It shouldn't be surprising that the diplomatic compromise of most rhythm games is to make the play about copycatting. But all hope is not lost for improvisational sound in video games. Enter Gabe Cuzzillo's Ape Out.

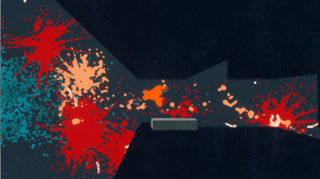

Ape Out's leading man is a gorilla who, in each section, breaks free of the chains of some human facility. For example, the lab where they're taken test subject or the high rise where they serve as an executive's pet. The experience should be recognisable for anyone who frequented Hotline Miami; you have a top-down camera, a melee jab, and labyrinthine level design which obfuscates enemy line-of-sight. You enter stages empty-handed and slight misjudgements in movement can leave you a bloody heap on the floor. Fortunately, the armed goons crowding the corridors go down in one hit, and you can seize their weapons for your own use. Both games recognise your kills and deaths through exuberant hyper-violence.

There are some noteworthy differences between the two experiences. While the Hotline Miami protagonists can knock down an enemy with their primary hit, the Ape Out player character can only push enemies as their default attack. However, causing two enemies to collide or flinging them into a wall is a death sentence for them. And while, in Hotline Miami, you must murder a man before you can steal their gun, the muscular ape is capable of lifting a whole person and having them spray at their allies in blind terror. In Hotline Miami, you can hold down "Shift" to peek ahead and get the lay of the land outside your immediate view, but in Ape Out, you have no such object permanence. The mechanical dissimilarities between these games are subtle, and yet their playstyles are disparate.

Hotline Miami always leaves you one stray round away from death, but at least on the normal difficulty of Ape Out, it takes more than a couple of bullets to stop your crime spree. Ape Out's levels generally have more paths snaking through them than Hotline Miami's, and in comparison to the first Hotline Miami, Ape Out has a softer spot for wide-open spaces. While Hotline Miami's gangsters are always quick on the trigger, the gun wielders' reaction times in Ape Out wouldn't get them through basic training.

So, with a little more forgiveness in Ape Out's play, you're encouraged to think less before you press. And you couldn't expend much brainpower on a plan of action anyway. Walls bend inwards blocking your view, enemy locations randomise when you respawn, and as mentioned, your vision only extends so far. It's a lesson on how a game's play is characterised as much by level design and the tuning of variables as it by the basic mechanics. It's also an example of how games which are harsher and bombard us with information about their play state are optimised for planning. In contrast, games which are laxer on us and have a low information output encourage improvisation.

Ape Out wants us thinking in the short-term and lashing out on impulse, just like an enraged zoo animal; this is where the musical lineup comes in. The experience's soundtrack splays itself over manifold schools of drum music that all carry a common attitude. It binds together sheaves of freeform jazz, tribal music, American military drumming, industrial, and bucket drumming. It has frantic percussion with a tempo and pattern that are always in flux.

The audio accompaniment of Cuzzillo's work was written, not by a composer, in advance, but is written by Matt Boch's procedural generation system, in real-time. It has to be, as we perform the play in real-time. Boch's engine samples from thousands of drum clips to colour-match a backing for our bloody escapades. The intensity of the drumming heats up as we draw gunfire and crush humans under our simian fists, then cools as we stick to the back channels and elude our wardens. In the second that we splatter an infantry member across a surface, there is a percussive strike, usually from a crash cymbal. It might seem impossible for a virtual band to match such spontaneous, intemperate behaviour, but Ape Out's elastic audio is more than capable.

By way of its percussion, the game finds a reprieve from having to construct melodies. Drumming is a note-free music form, and so, you don't have to fret about chords, harmonies, or melodies which takes a load off of anyone procedurally generating music. Perhaps the most significant advantage it lends this experience is that the developers don't have to ensure the notation in one loop will lead smoothly into the next. Perfect when you may have to switch tracks briskly because the player suddenly turned 180°.

Drum patterns also stand up to repetition, whereas the harmonies of other instruments have a shorter expiration date. This is why musicians can lay down "drum loops" which sit behind a track cycling through the same motions as other voices go off on winding rambles. So, if Ape Out's engine reuses a drum part we've heard many times before or keeps echoing a sample, it doesn't become tiresome. Play works in cycles, so Cuzzillo finds a soundtrack that does too.

The soundtrack's chosen genres support both the need to keep up with stochastic player performance and embody the title's themes. Militaristic drums encapsulate the game's vibes of violence and confronting an onslaught of armed hostiles. American military drumming was also a progenitor of improv jazz drumming. Experimental jazz has been a genre long recognised for subversion of typical conventions and for its eccentric use of structure and timing. So, if the music steps up or down in loudness and tempo curtly, that sounds appropriate for the style. As does it when there are metallic clangs at random intervals in the sequence; jazz drummers like syncopation.

We'd also expect to hear some dirtiness in the bucket drumming, a musical method that hails from the streets, utilising whatever materials are available. And it's not unusual to find an improvised sound in much non-western folk drumming; those creeds of percussion, much like the jazz drumming, often transcend our western concepts of how music should come together. Again, they're forms which moulded jazz drumming and a great addition when procedurally generated music won't match conventionally consonant patterns. These musical persuasions which aim to break out of their box and overturn the rules reflect Ape Out's narrative and play which have us fleeing captivity and wreaking chaos as we do.

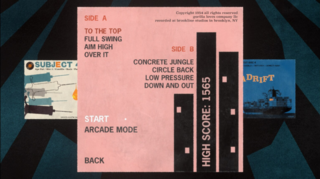

That drums are Boch's instrument of choice also speaks to the character of the protagonist. Drums are blunt, stirring, and impactful, just like our red-eyed primate. The game further fashions itself as a musical experience by splitting its levels into "discs". Each disc has a "Side A" and "Side B", tucked inside an EP-like cover. And as Cuzzillo breathed life into this game, he had one particular free jazz piece pinging around in his head: Pharoah Sander's You've Got to Have Freedom. The 1987 song also makes an appearance in the credit sequence.

We've talked about the limit-breaking nature of free jazz drums, but this track throws something else into the pot. In it, we hear Sanders's distinctive use of overblowing: a technique in which he pitches his saxophone up not by pressing the keys on it but by pure force of his breath. It paints that out of control, no-holds-barred colour that winds through Ape Out. It also feels intentional that we get these triumphant horns entering the soundtrack only after the prestige of the gorilla's final breakout.

We've now talked about improvisation and impulsiveness with regards to the protagonist, play, and music of Ape Out, but how does it translate these themes into graphics? Cuzzillo has a few bright ideas. Firstly, he implements a camera that hovers feet above the killing floor and sprites with very little detail or colour range. Nothing is too complicated; it's all just a human, a fire, a wall, and so on, just as the primate sees it. But the animation of the gorilla is undeniably realistic, giving us the impression of organic, progressive motion.

Secondly, when we die, the game zooms out on the level and scribbles a line through it, tracing the route we took. This line is as disordered as our improvised escape attempts, like a length of string left in someone's pocket. These retrospectives also emphasise that no two runs are the same.

Thirdly, the game's visuals can't sit still. That's partly because we're always on the move, putting distance between our hunters and us, and searching for the exit. But more unusually, all the walls and floors shimmer as if they're painted cards flashing in stop motion. They're never light or dark in the same spots second to second. Meanwhile, torch beams fizzle with noise, and title cards for levels jump with fright at the clap of percussion.

The game's flat graphical representations and kinetic typography are the stuff of Saul Bass. Collaborating with the likes of Hitchcock and Scorcese, Bass was an artist who revolutionised film title and poster design. While marketing in the golden age of Hollywood often used photography or realistic illustration, Bass's art broke images down into base geometry which more elegantly communicated what was happening in the film. Where credits were once formal text crawls, Bass reimagined them as minimalist replications of the movie as a whole, anthropomorphising shapes and writing.

In relevance to Ape Out, it's worth mentioning Bass's contribution to the 1955 film The Man with the Golden Arm. Directed by Otto Preminger, The Man with the Golden Arm tells the story of an aspiring jazz drummer fresh out of prison. Bass also fashioned the intro for Preminger's Anatomy of a Murder, a meet-cute between a cutout of a dead body and playful yet ominous jazz. Again, it's not hard to link that back to Cuzzillo's game.

I find that free jazz and modern art are interests which people often think you need five years in university to appreciate. And a dependable knowledge of theory can boost your enjoyment, but at some level, all art has a sensory component that either jives with us or doesn't. No matter how high-brow the styles Ape Out draws from, we can all see their appeal within the game.

The minimalism is pleasing because it frees us of the heady task of taking in countless data. And the kinetic typography and free jazz are invigorating because they're about tearing up the rulebook and expressing our energy without self-moderation. Pharoah Sanders and Saul Bass can fill our living rooms with joy for the same reason that lumbering through a video game level crackling skulls can: Because freedom is often about acting as the mood takes you rather than performing within a stringent ruleset. Freedom is improvisation. Thanks for reading.

Log in to comment