In the dedicated game design community, it's common to treat tabletop game design and video game design as unified, or at least, closely intertwined disciplines. Video game design classes have students analyse board games, and plenty of studios have prototyped systems for software games using pen and paper facsimiles. But people who don't have an academic or professional connection to games often place an impassable divider between board game design and video game design. They cast them as chalk and cheese, oil and water.

Video Games vs. Tabletop Games

If you are having trouble seeing the common ground between these formats, think about the features that tabletop and computer games share. Broadly, these two media are interactive experiences in which rules and goals mediate our actions. More specifically, examples in both categories have us manage resources, adapt to economies, strategically deploy abilities, and navigate maps. Various video and tabletop games have us commanding units with unique movement patterns or powers with which we can act on an environment or other units. RPG tropes like loot drops and experience points, that have expanded to fill the whole gaming space, originated from pen and paper role-playing activities. What unites tabletop games and video games is their logic and structures; part of what distinguishes them are the interfaces through which we interact with that logic and those structures. Input devices, screens, and speakers with the one format, and cards, pieces, and boards for the other.

I think professionals and audiences disagree about the symmetry of these media because we're approaching video games from opposite ends. The software designer experiences the game systems first, creating and tuning every one of its mechanics from the ground up. They're conscious of their game's rules, incentives, and goals and can see parallels between them and the rules, incentives, and goals of tabletop experiences. The player experiences the game interface first, with much of the underlying systems obscured.

For video game developers, it's often extra labour to externalise information about their games' internal workings to players. They also don't want to overwhelm or confuse the user, have their game appear systemically cluttered, or surface information that would work against the game's aesthetics or compromise its challenges. Therefore, the typical player is only aware of the information they need to play a game and the interface for interacting with it. Data like spawn rates or AI routines go under the radar, and otherwise abstracted game design concepts are presented to players in a way that is easier to understand and often fits into the style of the game. Therefore, audiences see what video and tabletop games don't share (their interfaces) but not what they do (their systems).

Given their shared rules, when we learn about tabletop games, we can learn about video games. But why bother with tabletop specifically? Why not just study video games via video games? It all comes down to how these games do their processing. Every game changes states in reaction to player decisions and sometimes autonomously as well. Within their systems, entities change position, certain values alter, the status of units shift, etc. In video games, a computer executes these state changes. In tabletop games, they're managed by players who shuffle cards, move pieces, add and remove counters, etc.

So, tabletop games have a lower cap on their potential complexity because humans can't process the billions of variable changes per second that a computer can. The relative simplicity of tabletop games makes it easier for novices to understand them in their entireties. Additionally, because audiences have to operate tabletop games, those experiences must be systemically transparent. Manuals and cards relay their complete rules to players, leaving them open to study. Whereas, to get into the guts of a video game, we need to take them apart in an involved and highly technical manner. When we can disassemble a video game, often it's only people familiar with design and computer science that can interpret the data. Returning to our thoughts about the perspectives that people approach games from, you'll notice that the player managing the tabletop game simultaneously grasps the systems and interface, getting a view on it not unlike the video game designer on the video game.

As proof of the overlapping principles between tabletop and computer game design, I want to pick apart one of my favourite board games. Ticket to Ride is a classic in the European board game style. Don't let its colourful plumage fool you. Alan R. Moon's masterpiece is capable of producing searing tension, and through it, we're going to understand how games, in general, can leave us in a state of suspense. To save on "ifs" and "buts", this description will only talk about the rules and dynamics of Ticket to Ride for sessions of three or fewer players.

The Rules of Ticket to Ride

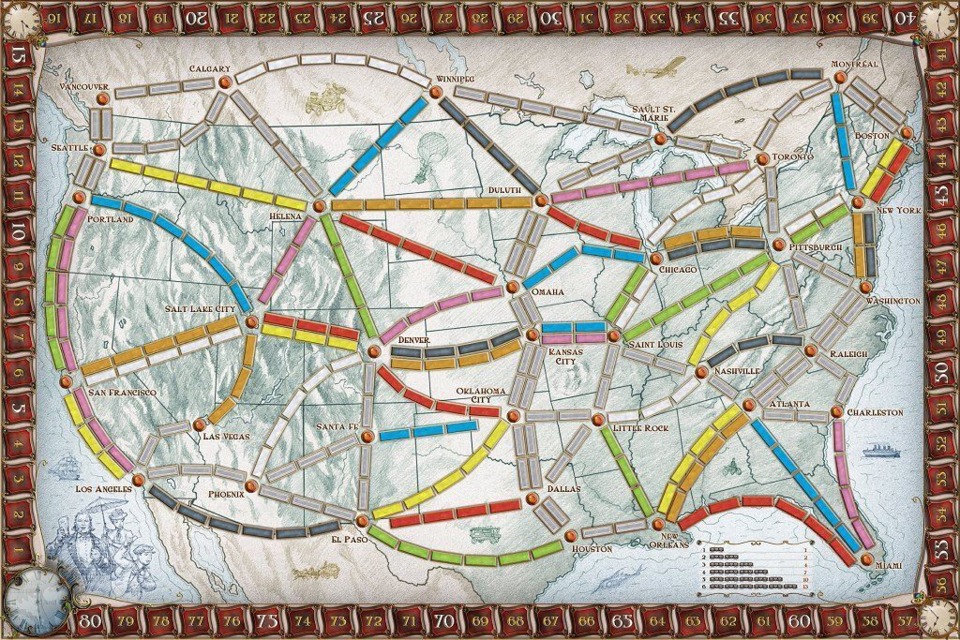

If you've played Ticket to Ride recently, feel free to skip ahead to the next section of this article. Otherwise, the rules are easy enough to learn. The game map is a partial cross-section of North America, with routes connecting major cities. Each of those routes has a colour and a length. Success in Ticket to Ride is measured in points, with players tracking their points using counters which move around the outside of the board. Whoever has the most points at the end of play wins.

The player can score in a few different ways, but the most straightforward method is claiming routes on the map. To claim a section of track, they must discard a number of carriage cards from their hand equal to the length of the route. All cards they spend must be of the same colour, and unless that route is grey, they must also be the route's colour. So, to take a route made up of three green spaces, the player must discard three green cards from their hand. For a five carriage grey route, the player could lay down five orange cards, and so on. Players indicate that they own a route by placing some of their coloured plastic train cars on it. When a player connects two cities, no other player can take a route that makes that exact connection. So, if you travelled the path from Dallas to Houston, another player cannot snag the parallel track that connects those two cities. Different route lengths score different points, but we'll discuss the scoring scheme later.

Players start the game with a handful of carriage cards (the cards they discard to claim routes) and a selection of tickets. Each ticket bears the name of two cities and a points value. If the player's routes connect the two destinations on the card by the end of the game, they earn the score listed on it. If they fail to connect those cities, that quantity of points is subtracted from their score. Players keep their tickets secret from each other until play is over and do not calculate how the tickets affect their scores until then. For example, if I hold a ticket for "Vancouver - Santa Fe" with the number 13 on it and I make a contiguous line of trains from Vancouver to Santa Fe before the end of the game, I win 13 points. Otherwise, I lose 13 points.

Each turn, a player can either claim a single route, pick up some coloured carriage cards, or draw more tickets. Say they want to nab some of those sweet carriage cards. They have some options about how they do that. There are always five face-up coloured train cards on the table, as well as a face-down deck. The player can pick up two cards on their turn, either of which can be from the face-up buffet or the draw pile. When a player grabs a face-up card, they replace it with another from the top of the deck. A player may also be able to take a "locomotive" card that can fill in for any train colour, but if they pick one from the selection of face-up cards, they do not get to take a second card.

If a player procures tickets, either at the start of the game, or voluntarily, on a turn, they receive a set number of them. There is a minimum quantity of tickets they must keep in each case, but they may also choose to retain more than the minimum. For example, if a player uses their turn to draw tickets, they pick the three from the top of the ticket deck. They must keep at least one of these cards, but they may keep two or all three.

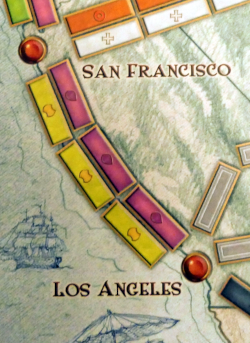

If this description of the game sounds a bit abstract, here's an example of what a couple of turns in Ticket to Ride might look like: Let's say I have a ticket that demands I make the journey from Duluth to Los Angeles, and I've claimed most of the routes between those two cities. I just need one more connection: San Francisco to L.A. If we look on the board, we can see that there are two possible routes I can take to make that link. One consists of three pink spaces and the other consists of three yellow. Therefore, I need to collect three pink carriage cards or three yellow carriage cards to claim the route.

In my hand, I already have one pink card but no yellow cards. So, I figure it will be easier to build towards the pink route. I declare that I will use my turn to take more carriage cards. There's one face-up pink carriage card on the table, which I collect, replacing it with a card from the top of the deck. The replacement card is white. There are now no pink cards I could take from the face-up set. I choose to draw from the deck, hoping I'll pick up a pink, and I'm lucky enough to have my prayers answered. On my next turn, I can discard those three pink cards from my hand and lay three of my train carriages on the pink route from San Francisco to Los Angeles. A three train route is worth four points, so I move my player counter up four spaces. As my "Duluth to Los Angeles" ticket is worth 12 points, I also know I'll receive 12 points at the end of the game. The game's final round is triggered when any player is left with two or fewer plastic cars.

Tension in Ticket to Ride

Every rule I've discussed contributes to the air of apprehension and anticipation that underscores the game. Firstly, look at how the route scoring scheme encourages risky play. Here is the table that shows how route length converts into points:

| Trains in Route | Points Awarded |

|---|---|

| 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 2 |

| 3 | 4 |

| 4 | 7 |

| 5 | 10 |

| 6 | 15 |

The correlation between the number of trains you place in a turn and the points you score is not linear. For example, the jump up in points between a two carriage route and a three carriage route is two, but the difference between a three carriage route and a four carriage route is three points. Here are the scores for each route length plotted on a graph:

The more carriages you add to your route, the steeper the points curve gets. Say you're in a position to construct a two train route; there's a strong incentive to hold out for a third card of the same colour because you'll get double the return. If you're in a scenario where you can lay down a five train route, it's tempting to wait for that sixth colour card because you'd get 50% more value. This is always a risk because the more of a colour you remove from the deck, the less likely it is that it will "spawn" again. Worse, the longer you wait to lay your route, the higher the chance that someone else will take it from you.

If someone else steals your route, there might not be another one of the same length and colour for you to grab in its place. For the six carriage paths, specifically, there is only one in each colour on the board. Notice that this becomes a bigger problem with an upward curving points scale rather than a linear one. Let's imagine that when we laid a route, we got the same number of points as the number of trains we placed: One point for one train, two points for two trains, and so on. In that case, if we were targeting a six train route and someone else took it from us, it wouldn't be a huge setback. We could take our six carriage cards and split them up to make a four train route and a two train route. It would take double the turns, but turns aren't that precious, and we'd still get the six points.

With the scoring scheme Ticket to Ride actually uses, we can't recover the same amount of points by dividing a long route into two shorter routes. Laying a six train combo is worth 15 points, but the combined profit from a two train route and a four train route is only 9. So, someone stealing a six train route from you is a big deal, and there's a reason to put yourself in harm's way to claim it. The disproportionate value of longer links then creates new conundrums for the player. If you were aiming for a four or five train route and then someone robs it from you, do you pursue a similar alternative route or try for another kind entirely? Both options stir tension in their own way.

It also bears mentioning that you're not usually trying to put down sticks on any route on the board. Usually, the optimal way to play is to take routes that help complete your ticket. So, if you're gearing up to connect two specific cities and somebody else does it first, there's probably not another route of the same colour and length on the way to your ticket destination. And in general, if another player blocks your passage, you're going to have to go the long way round, spending more trains and turns doing so. If it's too inefficient, you may have to abandon your ticket entirely and take the hit to your points. But when do you call it quits? At what point is a ticket "ruined"? There's always the potential you've abandoned a trip you could have rescued or wasted your resources on a journey that will give you fewer points than an alternative.

Often, players become flustered when opponents start laying carriages in the general vicinity of where they plan to place their trains. The opponent's placement suggests, but does not guarantee, that they may have a journey that overlaps with the player's. There are plenty of tickets that run through the same rough areas on the board. You could try to prevent a clash by picking tickets with shorter journeys that are less likely to conflict with others' and that won't carry a severe penalty of points or turns if left uncompleted. However, you may want your route to conflict because it will let you block other players from finishing their tickets while awarding you points. There's also no promise that when you take tickets, you'll draw shorter trips or that they won't clash with opponents'.

Plus, much like with the routes, there is not a 1:1 correlation between the length of a ticket journey and the points you receive. If the origin and destination on Ticket A are twice as far apart as the origin and destination on Ticket B, Ticket A will not be worth twice the points of Ticket B. It will be worth much more than twice the points, so there's again a risk in all choices, and that risk creates tension. There are other reasons that picking your tickets can evoke anxiety.

Ideally, when you draw tickets, many of your journies will overlap, letting you complete more tickets with fewer routes. So, each time you dive into the ticket pile, you'll have some anticipation to see that happening. But those tickets may not converge and could even demand that you make journeys far across the map from each other. This would be a trivial setback if there were no points penalty for failing tickets. You could ignore the goals that are awkward to pursue and focus your efforts on the lucrative ones. It would also be a non-issue if you could discard any tickets you picked up, but you have to keep at least two of the tickets you draw at the start of the game, and at least one when drawing tickets at any other time. So, when you draw tickets, you're always investing in the outcome of at least one, no matter how inconvenient it is to fulfil.

Taking fewer of these cards can reduce the chance you'll end up with incomplete routes and pay the fine. However, you need to make sure you're completing a healthy amount, or other players will do so instead and fly past you in the scoring. Therefore, you are pressured to draw more tickets. If you could see your opponents' stubs, you'd be more secure in choosing whether to take on longer and more journies, but you can't. You can only make educated guesses about the state of your opponents based on their behaviour.

If you are worried about opponents eating your lunch, you could always install your routes as quickly as possible, precluding them from capturing the same territory. You would place a route, take many turns to gather the cards to tick off another, and repeat. The problem here is that you're cluing your adversaries into where you intend to build and giving them plenty of time to cut you off. Therefore, the strategy of holding back placements until you can make many of them quickly becomes tenable, even if it carries the risk that someone will sweep the rug out from under you in the meantime.

Planning where and when to place is stressful, but you might think that the simple act of drawing cards is at least a more placid phase of the play. What could be tense about picking a couple of new items off the table and putting them into your hand? As it turns out, quite a bit. Drawing from the deck builds some tension because you don't know whether you'll get what you want, but also consider the face-up carriages. Sometimes there will be two cards you need just sitting in the open for you to collect. There are eight different colours in the game, plus locomotives, meaning a good chance that one of the five public cards will hold some value for you.

Yet, often, you'll find face-up cards that might help a bit but aren't ideal. Say you're trying to collect the carriages to make the trip from Salt Lake City to Denver. There are two different routes between these locations: one that requires three yellow cards and one that requires three red cards. Now, imagine you had two yellow cards in your hand but no reds. However, there's one red card face-up next to the deck, but no yellows. You could pick up the red card because that at least guarantees you progress towards the route, but it comes with the disadvantage that you'd need two more reds to complete it. If you draw from the deck, you'd only need one yellow to finish your route, but there's no guarantee of getting a required card from the deck like there is when you take the face-up carriage.

Face-up locomotives create a similar dilemma. Pick up one of these wild cards, and you'll have a resource you know you can use, regardless of the route you're tracing. Locomotives also provide insurance against other players blocking your travels. If you were going to use your handful of black cards to lay a route and a player snatched it from you, those black cards might now be useless to you; you have nowhere that advantageous to spend them. However, if you were going to use a locomotive to contribute to a route and it is stolen, you can simply transfer it to another colour route. The superpower of the wild card is its flexibility.

Yet, if you choose to pick this rainbow card from the table, now you're only getting one new carriage on your turn when you could earn two. It's common to need another card for a route but not find it face-up on the table. The locomotive is though, posing a difficult question: do you settle for taking that one card from the table or do you gamble by trying to draw two random cards from the deck? Again, the design is making you sweat a little because significant points could ride on finding those cards.

Just as it's tense watching your opponents lay routes, you often can't relax when your opponents are picking up cards. There may be face-up carriages you need on the table, and with each opponent's turn, there's the chance they'll secure those resources. Even if they don't, them picking up certain cards suggests that they may be building routes where you wish to. If you need to fill in those four orange rectangles and your opponent starts picking up oranges, you could be in trouble. And your opponent may be getting nervous because maybe you've figured out where they're placing and are thinking about getting in their way. But notice that none of these clashes is assured; there's always a chance you're still in the game.

Even working out whether to lay cards or take cards can create some friction. Hesitate, and you could lose your place, but place, and you could miss out on picking up face-up cards that are useful to you or other players. Keep in mind, the whole time that competitors are scoring points, they're moving their counters around the edge of the board. It's possible to play Ticket to Ride without performing real-time scoring; you just add everyone's points up at the end. But not only are opponents' scores valuable data for strategising; they also turn up the heat on you. You can see that a fellow competitor is seven points ahead of you or just three steps behind. Because the score is displayed in this spatial medium with a counter and a path rather than as an abstract number, it is realised in a concrete sense that has the power to elicit more emotion. Play becomes a frantic chase rather than competitive accounting.

Ticket to Ride can organically produce moments where players suddenly catch up and slowly fall behind. If a player is traversing shorter routes, they're going to move their counter up frequently. Players working on longer routes won't be scoring as often as they need time to collect cards. And so, those travellers taking the lengthier trips can feel the strain as they watch rivals inch ahead of them. But when they finally construct a set of many of the same colour, they can suddenly leap forward. They may jump over players who've been able to squeeze in front of them. If they don't, they may at least be breathing down the other player's neck. Miraculously, even when you learn how this elasticity is baked into the rules, the game only becomes more tense, not less. Because now, if you've got a clear lead on another player, you're more aware of the possibility that they'll catch up, and vice versa.

And the score counter is only a prediction of how the game will end. Not only will scores fluctuate while play continues, but tickets stay secret until the dust has settled. That confidentiality is paramount for keeping players uncertain of the game's outcome unless one player is leagues ahead of everyone else. You might have held your own when it came to direct scoring but have come up short on ticket score without knowing. Or you could have earned only pocket change when placing your routes but have a colossal lead on your ticket points, unbeknownst to you.

Vital for maintaining that uncertainty is tickets not only awarding points but also confiscating them. If you could only receive points from completing journies, then during the late game, you might add up all your tickets and find it's not possible to catch up with a player in front of you. However, if you know there's a chance they could move backwards in addition to you moving forwards, you're aware you could still beat them, raising the stakes.

Abstracting from Ticket to Ride

So, that's how Ticket to Ride creates tension. To take lessons from this design that we can apply to other games, we need to look for patterns in its play. The more abstract the patterns, the more widely applicable they are. I think the broadest lesson we can fish from this pond is that tension arises when we feel simultaneously close to winning or losing something that matters to us. As such, it is a product of our investment in a game and is a very close cousin of engagement with a game. We feel apprehension when another player might take the carriage card we want because we care about getting enough cars to build our route. We get a sinking feeling when seeing an opponent's counter gain ground on ours' because we would like to win.

If we thought we were guaranteed to lose because we'd fallen far behind or that we had a 100% chance of winning because we were so far ahead, we'd feel no suspense. It's at the point that our success or failure looks fragile that the tension begins. It may seem impossible for there to be more than a few potential turning points in a game of Ticket to Ride, and to some extent, players aren't constantly threatened. But the suspense persists because Ticket to Ride is full of non-commital hints that the player might be in danger. Someone whose score is meagre during play could be holding onto a killer hand of tickets. You probably can't count them out of the running. When an opponent picks up a colour you want, you don't know they're working towards the same route you are, but they might be. Genuine threat cannot be ever-present in the play, but its suggestion can be, pushing the player to remain vigilant and put their best foot forward.

The game can create the lingering impression of danger regardless of your exact circumstances by surfacing some, but not at all, information about your opponents' states and intentions. If we could always see our opponents' completion, goals, and resources, we would be privy to some schemes that could interfere with our own, which creates some tension in its own right. However, we'd also have a clear tip-off of their plans. Plus, if we knew that they were steamrolling us, we'd be able to resign ourselves to failure.

If the game worked on the opposite extreme and we had no information about other players, we might grow a little paranoid, but it wouldn't realise the threat of our rivals on the board or in the cards. Their enmity would feel a little unreal. However, Ticket to Ride comes down in the middle. It shows us where an opponent is building their current line but doesn't reveal where their ticket has them travelling overall. We can see what they take from the face-up cards but never their full hand. Their potential to damage us is palpable, but the damage is loosely defined, prompting us to fill in blanks in our knowledge of the game with disastrous or brilliant scenarios. The inverse pressure is present in the game in that there is no way to advance our plans without exposing actionable information to our opponents. Every route we paint and face-up card we collect is an errant transmission of our intentions that they could use against us.

Further, Ticket to Ride makes the small tasks matter through a trickle-down importance. If you care about winning the game, then you care about scoring points. If you care about scoring points, then you care about completing tickets. If you care about completing tickets, then you care about laying trains. If you care about laying trains, then you care about collecting carriage cards. If you care about collecting carriage cards, then you care about what you can pick up from the table. All tasks you can perform in the game contribute to the ultimate task, whether indirectly or directly. Crucially, the relationship between those smaller tasks and our success overall is self-evident. Through the game's simple mechanics, we can all understand how each choice we make plays a role in our chance to win.

Lastly, Ticket to Ride generates tension by keeping all players in constant competition for the same limited resources: carriage cards and spaces on the board. This tiny stash of goodies inevitably ignites micro-competitions within the larger competition. That conflict means that players do not simply feel like they are working on competing projects alongside each other but clashing directly with each other, which is a higher pressure state to be in.

This competition further antagonises us by pitting us against agents hungry to take away the resources we require within some indefinite timeframe. There is a fuse on every one of the valuables in the public pool, which can again produce leisurely stress. That tension appears in both the most minute decisions and in the bigger picture, which means that it exists both in the short-term and long-term.

Let's reiterate our key findings from Ticket to Ride:

- Players experience tension when they feel there is a fair chance of either winning or losing something that matters to them.

- Even when there is no direct threat to the player's success, games can create tension by selectively hiding and revealing information to suggest the player is in danger.

- If the long-term macro-level tasks in a game evoke tension in players, and more immediate micro-level tasks transparently determine player success at those macro-level tasks, those micro-level tasks will also create tension.

- Designers can create tension by making players compete for limited resources.

Once you start looking for a few simple ludological principles like these, you'll see them everywhere. We extracted them from a board game, but I can show you how to identify them in a card game, a video game, and a sport. In each example, feel free to skip ahead to the line break if you already know the rules.

Generalising Beyond Ticket to Ride

Example #1: Bohnanza

Bohnanza is a card game about rival bean farmers. Players have two plots of land and can plant one bean species in each, with all beans represented by a card. Any beans of the same species can be stacked atop each other in a plot, but if a player wants to plant a new species, they must "harvest" (i.e. Discard) all the cards in one bed to lay their new card. When players harvest a bean field, they gain a number of coins dependent on the quantity of produce they harvested, as indicated on the cards. E.g. If you harvest two chilli beans in one turn, you get six points, but if you can harvest three, you get eight points. However, picking a lone bean always yields nothing. The winner is the player who has the most coins at the end of play.

Each player's turn consists of three phases:

- They plant the frontmost card of their hand and, if they choose, the card behind that. They may have to harvest a bean field to place the new card, even if they don't want to.

- They draw two cards and place them face-up in their "trading area". They may then trade those face-up cards and any cards in their hand to opponents. All traded cards go into a player's trading area, and when the active player declares the trading session over, all players must plant the cards in their plots. Again, even if this means harvesting current crops.

- The player draws cards from the deck and places them at the back of their hand. Note that players can never re-order their hand.

___

So, let's take our sources of tension from earlier and see where we can find them in Bohnanza.

The possibility a player will win or lose something that matters to them.

At any one time, a player is never that far from potentially planting more of a species of bean they are already growing, winning them some coins. However, they also constantly contend with the threat of them having to plant a new species in one of their existing fields, discarding their current crop before it can grow to be highly profitable. It's not unusual for there to be one of the species of beans you want to sow further down your hand, so you're trying to eke out the turns until you can. However, you're always drawing cards you may be forced to plant, especially if you can't offload your junk cards in the trading phase, so your plots are always in jeopardy.

The game selectively hiding and revealing information to create the suggestion of danger.

We saw a basic paradigm in Ticket to Ride, which carries across many tabletop games: the table plays host to information public to all players, but players also have a hand of cards that only they can view. Participants also cannot observe cards in a deck, keeping the future uncertain, and therefore, making the present tense. Both Ticket to Ride and Bohnanza sort neatly between information known to everyone, information known only to select individuals, and information known to no one. This effect arises in Bohnanza in forms that it doesn't in Ticket to Ride due to how Bohnanza has players order hands and trade cards.

Because players can see the upcoming cards they can plant and know there will be phases in which they're forced to play cards, there is a clear impression of impending doom. Those problem cards may not ever get placed into a plot. The player might be able to trade them off and acquire cards they want from other players or the deck. However, as both the deck and everyone else's hands exist behind an impenetrable veil, the player can see much of the curse but little of the cure.

Micro-level tasks clearly feed into important macro-level tasks.

This one is usually pretty easy to detect in games because they want you to know how and when to get ahead and when you're succeeding. In Bohnanza, collecting the right cards and trading away the wrong ones can help you plant only the ideal beans. If you plant the seeds you want, you can harvest a bountiful crop of beans, earning you a fortune of coins, which is how you win.

Players competing for limited resources.

One reason a lot of games feature markets is that markets are about battling for limited resources. In Bohnanza, farmers all want certain beans from the deck. However, there are only so many of each to go around, and Bohnanza makes competition very direct through these trading windows in which players must hash out who gets which materials. Of relevance, bean cards display how many of them you'll find in the deck. So, the rarity of the resources is always disconcertingly staring you in the face.

Example #2: X-COM: Enemy Unknown

Let's be real; you probably know this one. In X-COM: Enemy Unknown, you defend the Earth against an army of malevolent alien invaders. Your war is fought across multiple turn-based strategy battles, with varying difficulty and rewards correlating to that difficulty. You don't have to fend off every attack, but you do have to make enough headway to expel the invaders eventually.

A "fog of war" hangs low over maps, keeping units hidden unless one of your agents has a line of sight to them. As your small handful of operators defeats enemies and emerges victorious from missions, they can earn upgrades. However, should any one of them die doing their duty, they're not coming back.

___

The possibility a player will win or lose something that matters to them.

Because X-COM is divided into these discrete battles, there is always a win or loss coming in the mid-future. As you can lose a skirmish and still ultimately progress, X-COM can also make it so that you have a reasonable chance of being defeated in each match without ruining the game's forward momentum. Outlasting any one clash is your squad. X-COM gives you these tactical assets you can spend hours training and equipping, potentially forming a sentimental attachment with. Because you must invest ample resources to get a highly capable soldier, they are very difficult to replace if you lose one. The game then keeps your heart in your throat by dropping you into clearings and cityscapes where one bad ambush is all it takes to have them erased forever.

The game selectively hiding and revealing information to create the suggestion of danger.

Not only does X-COM employ fog of war, but it will also make you aware of roughly where in the nearby fog enemies are moving and fortifying. Aliens may even retreat into the darkness when wounded. So, we know vaguely where belligerents could lurk but not their exact location, or until we find them, their stats and weapons. That's scary. The game will also drop new extraterrestrial types into the fray with no warning. So, there's the possibility that, skulking in the shadows, is a monster you have no idea how to fight.

Micro-level tasks clearly feed into important macro-level tasks.

Upgrading and equipping your units to create a well-rounded team is essential to performing in battles. Within those frays, unit placement and actions can also be the vital ingredients that let you defend against specific enemies. Overcoming those enemies then enables you to win the battle, contributing to the war effort. Win enough fights, and you eventually complete the game.

Players competing for limited resources.

I'm using X-COM as an example here, in part, to show that you can't have players compete for resources without players, simulated or real. In Enemy Unknown, the user faces off against the computer for advantageous spaces on the map like cover and higher ground, and each party wants to preserve their units.

Example #3: Soccer

Put the ball in the net.

___

The possibility a player will win or lose something that matters to them.

Your team wants to retain possession of the ball. More generally, you want to keep it in a certain area of the pitch because it's your and your opponents' tool with which to score points.

The game selectively hiding and revealing information to create the suggestion of danger.

Sports tend not to have a lot of confidential information. The explanation for that gets a little complicated, but it's generally true that the more physical the game, the less it involves tactically deploying certain assets and abilities. And it tends to be those assets and abilities that strategy games hide. Yet, uncertainty always exists: mostly uncertainty about the future state of the game. Although you don't always know what your opponent is going to do next, you can infer possible outcomes from their positions on the pitch, the location of the ball, their previous actions, and even their body language. Supporters of a team tend to get vocally nervous when the ball moves towards their goal because of what it suggests will happen.

Micro-level tasks feed into important macro-level tasks.

Dodging around players and successfully passing keeps the ball in your possession. Keeping the ball in your possession allows you to move it closer to the opposing team's goal, moving it closer to the opposing team's net makes it easier to score, scoring earns points, earning points helps you win.

Players competing for limited resources.

Specific spaces and the ball are both limited, contested resources.

___

To explore all sources of tension in these three examples would take more dissecting than we have room for here. This article is already about 7,000 words. But hopefully, you can see how recognising the universality of game design concepts allows us to expand our understanding of the medium. When we see video games as only related to video games, we have a considerable knowledge base to draw from. Yet, when we can analyse video games through the lens of board games, card games, pen and paper games, or many other formats, whole new universes open up to us. Thanks for reading.

Sources

- Game board image taken from Ticket to Ride page on Board Game Geek. Ticket to Ride by Days of Wonder, submitted by Fawkes, borrowed under Fair Use.

Log in to comment