It's been a little over three years since Frictional Games released Amnesia: The Dark Descent. Frictional has been making horror games for years, but Amnesia was something else, a horror tour-de-force that ditched combat and focused on players hiding from creatures in the dark.

For many, including yours truly, it was a revelation. Horror games have struggled for an identity since AAA games left scares behind in pursuit of a larger audience with action and set pieces. It's been a long time since Resident Evil's dogs jumped through the window, but we've gained a set of talented creators with a new bag of tricks.

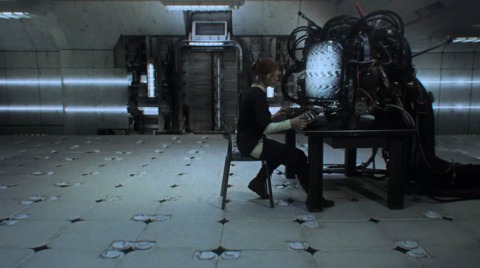

It would have made sense for Frictional to develop a sequel to Amnesia, but that job was passed off to Dear Esther developer The Chinese Room. Amnesia: A Machine for Pigs was more of a Dear Esther follow-up set in the Amnesia universe than a proper sequel, but that's because Frictional has been focused on SOMA.

SOMA has been teased for the past few weeks with a series of live-action scenes setting up a world where it's unclear who's human. The very concept of the soul is a question at the heart of SOMA, as Frictional co-founder Thomas Grip explained to me last week. Sadly, we won't be playing it until 2015.

Funny enough, we hadn't planned to talk about SOMA. I'd booked time with Grip about the development of The Dark Descent, but the first teaser for SOMA had been released that morning. After agreeing to push the interview back to the game's reveal, we covered both during our near hour-long conversation.

If you'd like to hear our whole chat, head over to the Interview Dumptruck.

Giant Bomb: Do you get nervous when you get ready to start talking about a new project, or there is more excitement about how you can stop being mysterious about it?

Grip: It’s a little bit of both because I’ve been wanting to talk about this project for two years or something like that. It’s a great relief, “now, finally, we can talk about something here!” So that’s great. But it’s nervous, as well. It’s always a problem about what you think other people are going to find exciting about a project. Obviously, since you’re so deep into it, what you find exciting about it might not be what other people are most excited about. When you first start talking about it, you try and feel the waters and get a nice feel for what’s interesting to other people, and how you want to approach it all. You’re sort of worried that you’re going to have an approach that’s not interesting to people. And all the reactions to everything--that’s always something to get nervous about. I’ve been super nervous the entire day, and have trouble [working]. “Oh, shit, the server’s going to go down” or whatever. [laughs] I’m just glad it’s all out there now. Now, stuff feels a lot better.

GB: What’s different about this project versus Amnesia: The Dark Descent is that Amnesia has had a pretty profound impact on the horror genre. You must have thought about that while planning your own next thing.

Grip: Yeah. You always have extra pressure because of that. I’m not sure how much impact we had, but we at least started out the whole first-person horror thing. But I think, perhaps, it would have come on its own. But, yeah, there’s a little bit of pressure there, wondering where to take it next. For this project, of course, we wanted to see what’s interesting, what are the next interesting steps here? You also have to be a bit careful in what you want to refine and what you want to do differently. You have a core of the game that needs to be retained, and I think that we did that.

Even if there’s tons of changing from Penumbra to Amnesia, there’s also a lot of similarities. This is not only for audience, [to ensure] they’re going to like the game, [and] they know that they’re prepared for the experience. They have the right expectations for it. It’s always that you need to be able to make the game in an environment that you’re familiar with. There’s a lot of feeling towards what we know, where’s our knowledge, what we’re good at, and what can we expand upon? Getting a feel for that is a pretty tough decision. We’re working a lot on this project. We’re trying new things. Didn’t work? Scrap that.

We did a similar thing for Amnesia. We started out doing a Super Mario horror game almost. [laughs]

GB: What do you mean by Super Mario horror game?

Grip: I think it’s just us being exhausted with doing these sort of games. They are very hard to do. Every single bit in a game needs to be coded specifically, so you have a specific logic for every little last thing in the game, with puzzles, scripted scenes, etc. We always sort of think “oh, this is too hard to make games, we need to make simpler.” For Amnesia, we actually thought “why can’t we have...in Mario, you have these bouncing platforms that you can bounce on and what not. We can have this small set of elements that we can just place and have in interesting combinations.” We tried building levels in that very early stage, so we have bridges you put down, you had ropes you can pull with levers, and platforms going everywhere. We just tried to build something from that. That didn’t work at all. [laughs] That was the big, first step.

I had an envisioning for Amnesia--and this must be six years back or something like that--that was like Super Mario 64. You go into all these different rooms and you can collect things and you go back to them [and] explore more. Just having this Brennenburg Castle that Amnesia’s set in, being something like that, where you entered rooms, you could solve some puzzles, flee from some enemies, and then go back into that room and you can have new objects and access different things. We tried doing that approach. We have this counter of how much percentage you had discovered and that sort of thing. But it didn’t work out at all.

I think the problem with that approach was that the reality of the situation was so abstract that it works in Super Mario. You have this Mushroom Kingdom that’s abstract and that’s the essence of the Mario world. Whereas in a horror game, you want it to be down-to-Earth, and that gets increasingly difficult the more more strange stuff you put into your level. When you want this sort of Mario-like levels, where you jump around and stuff, that requires these huge rooms that can fill these things. Normally, in horror, you want cramped spaces. It didn’t work out at all for that thing.

The whole darkness system, where you’re afraid of darkness in Amnesia, was sort of...we had that as a core idea, but we had that as a core gameplay mechanic. You were supposed to do a lot of stuff with the lights. Turn on a light here, and that can open a door. Turn on a light there, that keeps enemies away. That sort of stuff. We tried to build a game around that. But the same problem propped up there. The lighting in a horror game is essential for the atmosphere, and once you start using it as a gameplay mechanic, it takes away a lot of the atmosphere. We just scaled down and stuff, and then we went back to our Penumbra core, and thought “okay, what elements do we have these design tests that we can put upon that?” Then, we used that as a foundation to do The Dark Descent.

GB: There’s always this tension of how much agency you give the player. Specifically, when you’re trying to generate scares. The horror genre, typically, generates a lot of that through scripted events--jump scares are an easy way that happens.

Grip: Yeah.

GB: It sounds like you guys tried to find a way to give the player a little more agency over the world, but started discovering some of the limitations that come with that.

Grip: That’s a very interesting point. I just want to point out here that the discussion of [this], we called it afterwards Super Mario Torture Porn--that’s what we were going for. [laughs] We thought “oh, there’s no game like Saw!” So we had this great presentation for a publisher, and it was the best presentation I ever made on a game. The game would have sucked! [laughs] But it was a great presentation.

That was a thing [during] the first half-year. Then, we went back to more traditional horror thing, and started thinking about that. One of the main ingredients for us is we want to have a game where you play from start to end. The player is constantly in control. There’s no cut-scenes whatsoever. Historically, what you’ve seen in horror games, is once you have an enemy reveal--I think DOOM 3 is a good example of this. Every time you have an enemy reveal, you take some of the agency. Basically, having a cut-scene [and] something happens. In DOOM 3, you have the camera [zooming] away on some distant objects, and you see all these things happening. When the creature is there and you’re ready to fight, that’s when you give back agency. But that’s sort of boring. Fighting a monster is not the interesting part of a horror game, it’s experiencing everything up to fighting the monster. That’s the interesting part. The reveal itself is the climax of all this. Taking away agency from all that, that’s not very interesting.

"Fighting a monster is not the interesting part of a horror game, it’s experiencing everything up to fighting the monster. That’s the interesting part."

There's other examples of this from Silent Hill 2. You have this great scene where Pyramid Head is doing crazy business with a mannequin in a kitchen, and you have James, the protagonist, hiding in a closet and just peeking out and seeing him doing all these things. Then, going out of the closet once, Pyramid Head is done doing whatever he’s doing, and then he can explore that environment. I didn’t really like this because we have a game here. It’s supposed to be interactive. Why is the best sequence in the game in a cut-scene? Why can’t I be the one standing in the closet, just looking out? Why does the computer have to take control of that?

That’s something that we wanted to do, and I think that we pretty much [did it]. It’s one of the things I’m most proud of, at least. We have a sequence in The Dark Descent, when you’re hiding, a monster breaks into the room, and there is a closet there. You hide in the closet, and you peek out, and you see the monster wandering around. Then, he walks out of the room again. That’s interactive. You can jump out of the closet at any point! [laughs] Which would be a bad idea. But few players do that, and they’re just going along with the mood. “Oh, it’s a closet hide scene!” And then they’re just hiding in a closet and going along with that mood.

But I think that many game designers avoid this design because “what if the player exits the closet? What are we going to do? We have to have a different scene! What if he dies out there? It’s going to ruin the moment!” But what they’re, in fact, doing is they’re ruining the moment by making it a cut-scene from the very beginning. There’s ton of examples of this in horror games, where you try to do horror movie-like angles and what not all through the experience. “Oh, the player should see a shadow running away in the distance! But that’s just going to happen for a fraction of a second, so we need to make that a cut-scene.” You take away agency from the player, and just let the camera do the work. Show off the shadow, and then give the control back to the player.

What we like to do is set up the situation in a way that the player is looking in the direction where the shadow is gonna be. Then, we can, perhaps--and there’s always a percentage this won’t work--but if the player is looking at the right direction in pretty much the right time--so you have a gap when it’s a good time to be looking at a certain decision--then you have the shadow coming up. If the player looks too late, just play the shadow anyway. They might end up not seeing it at all. You have maybe 10% might not ever see the shadow, but the 90% that do are going to have a great experience, a much better experience than what you would have had if you had gone for a solution that you would know 100% sure that everyone would see. It’s a tricky way there in how you’re going to do this sort of thing, and it’s something that you’re exploring all the time.

GB: When you put the player in control, you can assume most players aren’t going to screw up that sequence, but the tension for the player is the fact that maybe you could screw it up. There is an element of chance that isn’t there the moment the black bars come up, and you realize they’re going for a cut-scene.

Grip: Yeah.

GB: Even though it’s, essentially, still a cut-scene, it’s the fact that you can still move around. You have agency, even if you have no interest in exercising it.

Grip: Yeah, exactly. You can also screw with this kind of expectation. You can have a very controlled situation, but because you know that you might be able to screw it up because there are situations that are screwable, [laughs] then you can have this tension.

Heavy Rain--there’s so much of this good stuff in Heavy Rain, even though it’s flawed on many levels, as well. But you have this death element. You know from the start that you can fail at any of the challenges, but there are only, say, five times in the game when you can screw up and a character dies. But this hangs over you all of the time. There’s one point where it can happen, and you can use that as well, in order to do this kind of stuff. In some situations, of course, when you want to have more exploration, it’s not possible to do it, but you can build upon this tension. If you just let it happen at some points, you can keep the tension going for the rest of the game. The first time you play it, you have no idea. “Is this a situation I can screw up? Is it not?” You can keep the player [on their] toes that way, and throw them a curve ball every once in a while to keep them on their toes. That also extends the feeling of agency. Even though there are a lot of times where you don’t have agency or control over the situation, just because you have had it in the past, it feels like you’re in control in those situations, as well. You’re the one that determines how this is all going to play out.

GB: Games are pretty unique in this way. If a sequence starts and the player fails the sequence, the tension is zapped upon the second playthrough. Even if they have the knowledge on how to complete it, it’s not nearly as scary the second time because some of the surprise is lost. There aren’t many of those sequences in Amnesia, but the chase sequence in the water is famous for that. I managed to finish it in one shot, so I had, essentially, the best possible experience with that--almost dying but not actually dying.

Grip: It is a spoiler, but it is a three-year-old game. We have a mindfuck in there for players. If they die two times, there’s going to be no water monster at all. They can walk through the entire sequence [with] no water monster, go through the gate--no water monster at all. And then you relaxed. “Oh, they just took away the monster!” Then, when you walk through the final door, it just bangs open and it just rushes at you! You can have these sort of things, as well, so that’s a good experience. He’s letting down his guard. “Oh, they removed the monster! It’s easy mode now!” BANG! You see the monster another time. You can work with that, as well.

It was a pretty late decision, I think the last half year. We just thought about it. Why do we have players repeating the same sections over and over again, this sort of trial-and-error? Can’t we do something else instead? Then, the idea there was that we have checkpoints the player goes back to, but we changed some stuff in the level--most of the time we do. Everything they’ve done, the current state, is still the same as when they died, so you have to collect the item or what not. But you have to go through a sequence, as well. Other times, we have them end up in a scary room.

There’s one point--I’m not sure if anyone did it--but you can drop down a well where there’s some splashes coming from. You’re [sitting] in there by this strange monster. Then, you will end up in this locked room where there’s more and more of this strange slime around you. You’re not sure what the hell is going on. You have to work a bit to get out of this room, and it just feels like you’re being devoured. It’s pretty rare the player experiences that, I think, because most people don’t jump down the well. [laughs] But I took it upon myself [to take a] couple of hours to implement a fun thing. This is sort of interesting to me. It might be that someone is very curious about what’s in the well. They’re not trolls. “Ooooooh, what’s gonna haaapppen if I jump down the well?” They’re genuinely curious and genuinely playing the game as it’s supposed to. When they’re at the edge, they slip! “No, I went too far!” And then they fall down the well, and then you have a special sequence. There might be a hundred players, in total, that gets this sequence, but it’s fun that you have [this], even if not everyone gets the sequence.

You have some people out there that are going to have a really cool experience just because of something you implemented. You try and balance that sort of thing. On the whole, of course, you can’t do things that a thousandth of a percentage are going to experience it. You have to balance the probabilities of these sort of things.

But back to your question, when you do you have these repeat sequences? We didn’t have much time to think about it in Dark Descent. We had a few days, in total, where we made most of these death sequences because most of the idea from the start was that you did die and start one of these sequences [over]. But what I think is that it’s when you bring the reality of the situation to the player. It’s the same with Heavy Rain and stuff like that. Heavy Rain is bad in that way because all of these things happen at the end of the game, they should have had characters able to die in the first scene or something like that.

But the same thing for us is that you need to have sequences where the player has to repeat a couple of times in order to finish it. You want them spread out evenly throughout the game. It’s important that they’re not too hard, but it should exist on a uniform basis to keep the tension going. Even if you’re trying to roleplay these kind of things--”oh, yeah, I know I won’t die at these things but it’s still freaky as hell so I’m still going to be scared of them.” You can’t keep that up for that many hours. They know, for instance, in the prison area, where some people went “screw it, I’m just going to run straight at every monster, so I just can finish it” because it’s so oppressing. That’s lost opportunity there. Because, then, you have someone that’s clearly not handling the situation.

As a horror game designer, that’s the best subject. [laughs] You don’t want to let them lose too easily. That’s the situation where you should have had a situation where you just had to repeat this over and over again. “Shit, argh! I can’t run at this monster anymore, I have to sneak here.” Make it a really oppressive experience for them. You have to throw these sequences here and there just to keep the player on their toes, but it’s a fine line. If you have them everywhere, then people are just going to “oh, no I have to game this, I have to figure out the system.” And that’s bad. Then, you’re taking them out of the experience. But if you don’t have them, then the players are going to figure out “oh, I can’t die, there’s no repercussions at all.” You have to have these sequences at some point to keep the tension up.

GB: Frictional’s been making horror games--Penumbra, Amnesia, SOMA--over and over. What brings you back to this every single time? I’ve never made a horror game, but based on when I’ve talked to designers, it’s very draining.

Grip: I’m not sure. There must be something disturbing in our minds. [laughs] Actually, when we started out on SOMA, the new game, it didn’t start out as a horror game at all. We had some thematics we wanted to explore, so we just went full ahead on that. “Oh, we can have some mysterious atmosphere, but we’re not going to go for full-on horror here. The thematics are going to be horrific in their own right.” But, then, as we started developing this, it just went more and more towards the horror genre. I can’t escape it. [laughs] I tried to not make a horror game, and it wasn’t possible. I’m not going to try that again. It takes long, so I’m just going to accept it. It’s going to be horror, whatever I do from now on. [laughs]

Horror is so great at bringing people into this very nice mindset that you just don’t get from other genres. When you’re in the scary situations, your mind starts evaluating the surroundings in a way that you don’t do in other games. When you’re playing a shooter, it’s all “oh, there’s cover there! He’s poking a third of his head out! I know I can snipe now.” You have to mentally, intuitively figure out where the hit boxes are and stuff like that. You don’t care so much about the background itself, you just know there’s cover there, now I have to reload, stuff like that. You’re viewing the game very mechanically. The way that you deal with that in games is that you have a very close overlap with the mechanical systems and the mechanical thoughts they bring forth. So in a shooter game, it makes sense to think about this because if you were a bad ass marine, that’s the way you would think about the situation and think about the environment.

But in a horror game, it’s different. You’re very exposed, and you’re in a situation where you’re not in control and you’re not aware of the mechanics. You’re not just trying to beat the game in a way that you’re trying to figure out how the enemies move and kill them. We experienced that a lot in Penumbra: Black Plague, when we went from having enemies that could be killed and having enemies that were not possible to kill, and you didn’t have any weapons at all. Players start noticing every single sound. It’s great when we saw playthroughs of Amnesia and stuff like that. Players just heard some footsteps, and it’s like “oh, shit! There’s something here! Where’s it from?” It’s just a background sound, but they tried to figure out “how does this figure into the world?” And you don’t do that so much in a shooter game because it’s known. If you hear a distant footstep, “okay, that might be some scripted event, there’s gonna come enemies soon enough, then there’s going to be fighting music, and we’re in our fighting scene doing fighting stuff.” You’re in that sort of mindset.

But in a horror game, you’re not sure what the hell is going on, and what’s going to happen next. Every single bit of the environment is something that you process in your mind model, and what’s cool about that is that in these shooter games, it’s very important that the mechanical mindset has a close relationship to what you’re actually seeing on-screen, and your intuitive view of the screen is very close to what [the] actual mechanical system is. But in a horror game, when done right, your mental view can be completely, utterly wrong when compared to the system that the game actually has.

We found that out with the sanity system for Amnesia. We first had it as something that you could game. You had to keep your sanity up in order to complete the game at all because it became unplayable, basically, if you didn’t have enough sanity. But once we relaxed on those constraints and the sanity system becomes more of a mute feature, player started to come up with their own theories on how it worked. “Oh, he’s doing that, he’s doing that!” That could work throughout the experience, and you have this mental mind model that was the players’ worst fears come true. We never in the game did something happened that challenged that notion, so the player could go on having this mind model that was a lot more terrifying than anything we could have done with a proper game system.

That sort of thing is very, very interesting in horror games, and, I think, why we keep coming back to them. As soon as you let that go and you don’t have this core threat of horror or threat of something hanging around the player and not having a determined way to deal with it, you get much more interesting responses.

Please enter your date of birth to view this video

By clicking 'enter', you agree to Giant Bomb's

Terms of Use and Privacy Policy

GB: Can you talk about the themes surrounding SOMA?

Grip: So the themes in SOMA is something I’ve been very interested in a long time: consciousness. You normally read about this in books and so on. You read about it in third-person. You read about it in neurological diseases and that sort of thing. It always happens to other people. But in a first-person game, we can make this happen to you. We can really make you experience these thematics in a way that I don’t think you could do in any other medium. It’s closely related to the horror, and we found that out later on. It works very well for a horror story. You have to figure out thematics on your own, and you have to build a mind model from them.

The sort of thing that we’re dealing with here is subjective experience, and what does it mean? What does it stand for? Is there a soul? If so, what is it made from? Could you switch to another body? That sort of thing. We have all these themes that go throughout the game, and that’s the core of the game. Putting you into situations throughout the game that deals with these sorts of themes.

We also have all sort of stuff build around this. The monsters--or the creatures--in the game all have different aspects of this. In order for you to combat them, at least as talked about in this mental mind model you’ve built up from listening to sounds and that sort of thing, all those are connected to this theme of consciousness. It raises all these sorts of strange questions in your mind, as soon as you try to figure out what these monsters are and what sort of dangers they can pose upon you.

GB: Can we expect that, mechanically, it’ll work similar to Amnesia? Non-combat? A lot of hiding? Or are you giving the player some new tools for dealing with what they encounter?

Grip: It’s still going to be a lot of hiding, but what we’re trying to do is that every creature in the game should be its own dynamic system. When you encounter a creature, that has a specific sort of system. Think of the sanity system. That’s a global system we had throughout the entire game. But in SOMA, for every encounter that you do, there’s going to be a dynamic system that’s like the sanity system but local to that encounter or species of creature alone. Each time you encounter a new beast or a new danger, you have to figure out how to work.

There’s going to be sort of tools, you could say, perhaps. Or just effects in the game that you have to figure out what they mean, and how to use these tools against them [and] to your advantage.

GB: There’s a movie coming out soon, Gravity, in which two astronauts deal with an emergency situation in space. It’s not something that games have dealt with too much. But space is sort of inherently terrifying, and I’m curious how you feel about it, and what do you think it is about space that puts humans at a deep unease?

Grip: There’s tons about it. It’s utter darkness, for one. It’s the embodiment of darkness because you’re so alone. Any sort of alien environment in that sort of way is going to bring out these [weird feelings] because you’re not sure how to deal with it. It’s just a matter of being utterly alone. In Gravity, they’re in orbit. No one can help you. If you try to return to Earth, you’ll just burn up in the atmosphere. There’s a very inherent scariness to being that alone. Even if you take the furthest reach on Earth, something like Mount Everest, if the weather is good, you could still land a chopper there and bring someone down. [laughs]

You see in stories a hundred years old, like Lovecraft stories, then it’s the Antarctic. Once you were there, there was no going back, there was no one to save you. It’s sort of like that in space, as well. And you have good horror movies come out of that, as well, like The Thing. Space is a step further than that. Because very few of us have been to space, it’s unknown what could be there. You expect anything to happen there, and I think that’s something that makes it very terrifying environment.

I also think the utter darkness of it all [is what’s scary]. You’re floating in darkness, in a sense. That’s just inherently scary.

GB: You have so little control over everything in this alien environment. In Amnesia, you’re in a castle. You have some sense of familiarity. You can breathe! You can flight a fire. There are things you can wrap your head around. But in space, it’s all predicated on technological progress, and the moment any one of a million things goes wrong, you’re at the mercy of something that is well beyond your control.

Grip: Yeah, exactly. The slightest thing can screw you up big time. At the same time, there’s also a bit of problem with space and strange environments. A good game example of this is the first Half-Life. Most of the players, once they get to the alien planet, Xen, then it’s not as interesting and engaging. Even though you’re in some pretty fantastic environments in Half-Life, they’re still grounded in some way.

You can see this in space movies, as well. You always try to ground it. The environment--it has chairs, it has televisions, and people [drinking] coffee or what not. If it’s totally unrelated to everyday life, then it loses some of your scary aspects, as well. You can’t attach to it in an intuitive fashion. You can’t just have something taking place in outer space, where there’s no human life at all. I think that’s just going to lose its scariness after a while because it’s not grounded. “Yeah, anything can happen here!” So you lose touch to it. You need a human touch for the attention to be there. I think that’s a very crucial aspect, as well.

GB: In Gravity, you have these two astronauts floating just above Earth.

Grip: Yeah, exactly.

GB: That grounds you because, well, it’s right there! But it doesn’t help you. I constantly thought of the film Alien while playing through Amnesia in terms of the way they kept the monster in the dark. Plus, in Alien, you go to the alien planet and that’s weird and strange and hostile, but where the true scares happen is in the familiar space back on the ship.

Grip: It’s the fix of familiar and unfamiliar. In Alien, what’s great about it is that when they land on this planet and enter this ship, everything is so utterly wrong. [laughs] You have the Giger designs, and it’s inherently really, really creepy. What happens is that when you go back to normality, that lingers in your head. You’ve just had a brief tour to this strange reality, and then you’re back inside. That contrast adds a lot throughout the experience. You can always refer back to that. What happens is that alien creature is, then, a manifestation of this really creepy environment that you were in before. You bounce off that. It’s sort of the same with Lovecraft novels. The character has these visions of a really weird reality, and that’s spooky and stuff. But the spooky stuff comes when he starts saying “shit, I’m seeing fragments of this strange dream in my own reality.” Then, it starts getting really horrific. The horrific stuff is not the strange reality in itself, but when it comes into your normal life in a way. That contrast might be how you build really good horror.

GB: I know some of the early speculation based on the little teaser that you guys have out there is that maybe there’s some influence from System Shock and SCP.

Grip: Both are actually inspiration. System Shock in a, perhaps, more implicit way. Every single game we’ve made inspired by System Shock 2, at least. [laughs] I mean, with audio logs and that sort of thing. It’s a great way of build a game. I just love the audio log stuff to death in System Shock. Even if it’s encounter-based in System Shock 2, you have this feeling the creatures are wandering about, having their own lives, even if it’s just “oh, you have an event, now let’s spawn some creatures here.” There’s this vibe to it that makes you feel [like that], and going back and forth between environments. Stuff like that. So that’s inspirational, but we haven’t had any sort of thematic [crossover] in terms of setting and stuff like that from System Shock.

"In a horror game, you’re not sure what the hell is going on, and what’s going to happen next. Every single bit of the environment is something that you process in your mind model."

SCP, on the other hand, there are two inspirational bits from that. I’ve discovered [it] fairly recently, and I love some of the stuff a lot. What we did is that we had the idea that “shit, this could be great for teasing material. We can have SCP-like entries on it.” It also had relevance [for the game]. We got stuck. We had, as I said, this thematic underpinning that we wanted to explore the consciousness and the A.I. and that sort of thing. We hadn’t really grasped how to do it because one of the things I didn’t want to do is that you could just have characters babbling about philosophical subjects while they player is avoiding monsters. That wouldn’t be right. That would feel like failure. I could just read a book and have that sort of thing. I wanted to do something that was [where] this could only be done in a game sort of thing.

Then, when we started reading SCP, it just dawned on me, “oh, it would be great--what if the monsters themselves are manifestations of ideas?” You can have this buildup as you have in SCP. There’s so much good in SCP. They start out each entry with just speaking about how you contain this creature. Shit, that’s just--all sorts of stuff springs up in your mind. You have a fleshed out mental picture long before they describe anything at all about the monster. You just weave that into your image, and it becomes so much more scary because of that. So what if you could have monsters like that? When you finally meet them, there’s aspects to them that deal with our thematic underpinnings with consciousness and that sort of stuff. You have to be very aware [of that] and think about [that] a lot when dealing with this creature. That’s the approach we took from that.

It totally transformed how we could approach the game. That was a major breakthrough in terms of “now we know how to approach this game.” We’ve been dealing with the game...it’s been in development for, shit, it’s gotta be over three years now? It’s insane! But we had [a] struggle with getting some of the stuff crossed, and when we finally just figured that out, it was just “Snap! This is how we’re gonna do it.” Both of those games have some inspiration, but it’s not like “oh, we’re gonna make a System Shock game” or “oh, we’re gonna make a SCP game,” but they sneaked into how we felt that we can approach the game.

GB: What’s becoming increasingly interesting as a potential tool for horror games is the Oculus Rift. As someone that’s crafted a lot of first-person horror experiences, have you given some thought to how this might intersect with what you guys have been creating?

Grip: I tried it out almost half a year ago, something like that. It’s a lot more effective than you think it would be, which is also the downside of it. It’s very easy to get sick in it. [laughs] There’s two [sides] to this.

I’m going to start with the bad stuff. For us, it’s two [things] that’s bad about it. First off, it’s visual effects. I’m not sure we could do any of the visual effects that we do. We do some zooming in when there’s a scary moment--we did it in Amnesia. There’s tons of this stuff. You change the field-of-view. I’m unsure how much of that you could really do in an Oculus Rift without making the player really, really dizzy. So I’m unsure. The thing is that those effects are not crucial, and you have other things in front of you when you’re using a Rift, but that’s designing two games in a way. You have to balance that sort of thing.

The other bad part is [considering] how we do interaction with this thing? I’ve tried Among the Sleep. The developers showed their game on the Oculus, and I tried it with their interface and it’s sort of cumbersome to use it. So I’m unsure. I only tried it for a few minutes, so I haven’t tested anything, but it seems that you need to simplify your interaction system in order for the player to be able to play a game for a long while. For instance, just to open a door [is hard], perhaps almost like some Heavy Rain-like [interaction]? When you’re near, an icon pops up in-game, when you’re in front of something. I’m unsure. But something like that, some simplified interaction system. So, again, that also means we have to do a different game, we have to design it from bottom up to be a Rift game.

But, then, on the other hand, there’s tons of good stuff. And the good stuff is VR stuff that, perhaps, not what you think about directly. First of all, it’s the peripheral vision. It’s so great for horror stuff. You can flicker stuff in the peripheral. How our brain works is that you’re very good at spotting movement in the peripheral, but you can’t spot any details at all. It’s exactly the thing we want out of a horror game. We can use that to our advantage. The player could be very aware that there’s stuff happening, but it can’t see it because it’s happening in the field-of-vision where they don’t have any possibility to see that happening. You can leverage that to your advantage.

The other stuff that’s cool is that you’re actually using gravity. You have the sense of balance, which is actually a sense of its own. You can use that to your advantage. For instance, I tried to the rollercoaster. Have you tried the rollercoaster?

GB: Oh, yeah.

Grip: I almost fell! [laughs] I’m afraid of heights, and it was just too much. I had to tear the helmet off me. “Shit, this is insane.” It’s all because of this sense of balance totally flips out on me. You can have this great vertigo scene in an Oculus. This sort of thing could be leveraged in a horror environment. So you could, perhaps, have the floor just slightly leaning. This kind of strange stuff, where you can’t peek up really, but your sense of balance is picking them up. So those kinds of things could be really cool for horror games.

But in the end, what I think is that it’s very important to remember that the best kind of horror--just like when you’re reading a book, it’s not like “oh, if this font was just a little bit crisper. It would be so much more scary” [laughs] Because it’s not happening in the pages, it’s happening in your mind. It’s the same with television and your computer monitor. It’s a feedback loop that you’re giving instructions to the computer, and the computer giving your something back. That collaborative work paints a mental picture in your mind. That’s where the scarier part happens. It’s when we leave gaps for the player to fill out, that’s when the true horror happens.

Even if Oculus Rift is just [has] the sense of presence grow a lot, you have the peripheral vision, you have the sense of balance, the monitor is in your face. Also, you have another feedback loop because your head movements start [influencing the game]. The virtual avatar you’re inhabiting, he reacts to your head movements. That adds another layer into how you’re building up your mental image of it all happening. But at the same time, it’s still the mental image that’s still the most important. It’s very easy to be very reliant on technology to building good horror, while most of the time, the best things are the things you cannot see.

That’s my thought process, but I’m very interested in using it. What we thought about doing, and I’m not sure if we’re gonna do it, but I really would be cool to, at least as a starting point, craft very specific Oculus Rift experiences. Then, have it along with the game or, perhaps, show off at some conference or something like that. That would be awesome. I have some ideas on how to do that. Then, you just do something that’s “this is made for use with this device.” That would be very cool to do. That has to take time from the bulk game, and I sort of want to get it done, as well. We’ll have to see what happens. [laughs]

GB: Speaking of which, are you talking at all about a timeframe when you’re hoping to release SOMA?

Grip: It’s gonna be 2015. I would love to release it next year, but with the quality that we’re going for, it’s not possible. So early 2015 sometime it’s going to release.