Despite its evocative title, the Assassin's Creed series may be more about movement and platforming than it is about elegantly planting blades into jugulars. While these games have a prominent combat system, the acts of getting to and from the combat, and all diversions from it, have you hot-footing it across rooftops and dashing through the open streets. Even the fights themselves are often a contingency for when you fail at stealthily skulking past enemies, and the assassinations are more about the movement system than the combat system. They may inherently constitute a violent action, but you only get to assassinate a target by navigating through the level in such a way that you can situate yourself behind or above them without alerting them. So when Ubisoft rethinks how we move through Assassin's Creed, they fundamentally change how we experience it. We saw this with Black Flag, an addition to the franchise which, by replacing horseback travel between cities with seafaring, felt more pirate-themed than it did Assassin's Creed-themed. Syndicate takes a similar tact, introducing a grapple hook and horse-drawn carts as the traversal mechanics of its Victorian age.

The inclusion of the grapple is a brave choice; it's an admittance that climbing, an activity that had pride of place in previous Assassin's Creeds, got tiresome at a point and is a chore that players are better for being able to skip past. The device further serves as an expression of the changing nature of labour during Britain's second industrial revolution when the game is set. The industrial revolutions were about taking previously manual tasks, and not wholly mechanising them, but at least giving people machines that let them perform those tasks more efficiently. So in Syndicate, we see the toil of manually leaping between handholds to scale buildings replaced by a gadget that allows us to rappel up whole walls with a single bumper press.

The grapple can also be used to create a zip line between buildings, evolving a concept from Black Flag. In Black Flag, abseiling down ropes made you feel that you were soaring through towns like an eagle and gave you a bird's eye view of the stunning surroundings, but there was little player agency involved: you could only ride these rails across pre-defined routes. However, with Syndicate's new tool, you can install a zip line wherever the fancy takes you. Being able to swing directly from rooftop to rooftop helps preserve the flow of the freerunning and banishes the pointless busywork of climbing down one building, running across the street, and climbing up another every time you want to cut across a road.

Both the grapple and the carriages are part of Syndicate's downplaying of the series' traditionally vertical movement in favour of more horizontal traversal. Less time is spent climbing, and the two most developed new tools in the game are mechanics for moving laterally across its simulacrum of 19th century London. The designers were forced in this direction because with each Assassin's Creed game expanding out the borders of the world, the time to travel from one side of the map to the other would have become unacceptably long by the ninth outing without a tool that lets you fast track it. The same logic may have inspired the naval voyages of Black Flag.

Note that Syndicate finds a way to include two methods of high-speed movement without one invalidating the other because they each lend us an advantage the other does not. The carriages are, by raw speed, faster than running and grappling about the place, but the grapple allows us to cut through buildings which is something the horses and carts could never do. Many single-player games empower us by letting us do what other characters in their worlds can't, e.g. Remaining standing in shootouts even when everyone else turns to a pulp or winning every match in a sports league as the teams that face us are doomed to failure. The special privilege Assassin's Creed lends us is the capability to scale the roofs and walls that no other citizen will lay a finger on. In Syndicate, even the air between the buildings is part of the play area. The title also manages to resolve another long-running divisive issue in the fanbase.

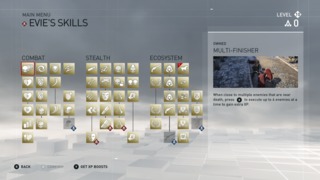

Assassin's Creed has flip-flopped between po-faced protagonists like Altaïr and Connor and more free-spirited assassins like Ezio and Kenway. No matter where Ubisoft plop down new protagonists on the serious-silly spectrum, they're going to be neglecting the portion of their audience which preferred the other kind of main character. Syndicate finds a solution in presenting two protagonists who represent the two different archetypes: The rogueish Jacob and the self-disciplined Evie. Although, we shouldn't ignore that it took nine mainline Assassin's Creed games for Ubisoft to feature one female protagonist, and even then, she's paired with a man to even things out. Mechanically, Evie and Jacob also blur together after a few hours.

The two protagonists share the same upgrade tree with only a few endgame stealth powers being exclusively available to Evie and a complement of fistfighting talents being uniquely available to Jacob. However, the upgrades you make to one of the characters will only imprint on that character and will not carry over to the other. Early on, the optimal strategy is to spec Evie in the direction of stealth and Jacob in the direction of combat because this lets you have all your bases covered while preparing the characters appropriately for unlocking their unique high-level powers. But there will come a time when you've unlocked all the stealth skills for Evie and all the combat abilities for Jacob. The only places left to put new skill points are in Jacob's stealth tree and Evie's combat tree, making them less individual as instruments in the play.

Evie also has a more dazzling late game power than her brother; while a well-trained Jacob is near-undefeatable in a brawl, at the same level, Evie will turn invisible while remaining still. Part of the reason you'd want Evie's invisibility over Jacob's invincibility is that melee tussles in the game are awkward and tiring, but we'll come back to that. We must also acknowledge that even if Syndicate does not pull out all the stops to distinguish these characters from each other in how they play, it does create an asymmetry between them through their differing approaches to problem-solving and thus the different missions they'll accept. Jacob's eye is caught by foolhardy schemes while Evie likes getting lost in research and is taking up the mantle of the Assassin's Guild. As a result, Jacob's missions tend to be more direct and action-packed, while Evie's require a delicate touch.

This is also an Assassin's Creed that has some thematic consistency for its side missions rather than them featuring a grab-bag of topics related to the era. As modern sciences take shape in the English capital of the 1800s, many of the supporting characters of the game offer quests with a rationalist bent. Charles Dickens needs your help dispelling superstitions, Darwin procures your protection while he publishes his theory of evolution, and Alexander Graham Bell wants your support in bringing London roaring into a new technological era. Considering this is a serialised AAA video game, it also takes an unexpected stand for leftist politics in some of these side missions. You and Bell wage war on a monopolising telegraph company with Bell's concern being that they are choking out smaller business and that such monopolies limit free speech. Karl Marx, who is regularly depicted in mainstream culture as a quack and cult leader, is seen by Syndicate as a benevolent and uplifting ideologist, working towards the same end you are. This attitude also somewhat carries over to the main missions: The villains of the game often try to defend their oppression of workers by saying they're the pioneers of society and creators of jobs, a common defence for modern-day captains of industry.

The setting of London is one that resonates a lot with me personally, and this game has been a reminder to me of how Assassin's Creed's format enables cultural representation. Cultural diversity is often used as a synonym for diversity in a cast, and having characters and actors of many different races, nationalities, and orientations can be part of cultural diversity, but the concept also means having a range of cultural settings in media. It's easy to characterise the time-hopping, globe-trotting iteration in the Assassin's Creed series as a cynical grift to reskin the same package year-on-year, but it is a way for people from many different cultures to see their heritage and landmarks represented in the series as opposed to the games being nailed down to one people and one society. Slowly, Assassin's Creed is writing more cultures and histories into the annals of AAA entertainment.

But for every rip in the fabric of the series that Syndicate patches over, there's another it brashly leaves on display or even rips anew. Everyone knows nannying an NPC is no fun; everyone except Syndicate which now contains missions where you must kidnap ne'er do-wells and shuffle them along to a destination at the most tentative pace possible. The game gives you all the controls to move in a soaring, fluid manner and then sticks you with these objectives that are about using none of them. And too many times in this game, you can't make short work of your enemies.

In an attempt to put more meat on the bones of the combat, the designers made it so that unless you're assassinating an enemy, you can no longer kill them in a single blow; striking them face-to-face just wears down their hit points. As a result, you spend a lot of time mashing on X to erode the blood-red bar above gang members' heads, and this creates a scrappy, sordid fighting style that matches the mean streets of a soot-coated London. However, encouraging the player to spam the same button over and over creates sloppy play and fails to put them in the body of these characters. When one press of a button lines up with one character action, you feel in sync with your avatar, but when you're pressing the button hurriedly, and many of your taps on the controller don't line up, you don't get that immersive sense of one-to-one control. Syndicate also has these hiccups where an enemy tries to strike you, but because you're countering another enemy at the time, they bounce off of you like a bar of soap sliding over porcelain. The designers of these fisticuffs have almost definitely played the Batman: Arkham games, but in Arkham, your attacks land consistently and quickly. That's the kind of snappy receptiveness that Syndicate lacks.

Both in confrontations and assassinations, your animations also don't look as clean as they did in past AC adventures. This change is deliberate and helps prevent repetition in the series, but I miss my characters being able to dispatch enemies with an effortless flick of their wrist. It made them feel like they were more on top of their task. Because enemies in Syndicate now have whole health bars you also sometimes get trapped in drawn-out punch outs, although higher level weapons eventually help you quickly cut down thugs. Through both the grapple and streets fights, this game takes quite a bit from Arkham and so feels less like its own person. In fact, Syndicate unintentionally raises a point worth memorising: It's less important that a game introduces new features to a series than it is that it introduces new features to the medium.

The horizontal grapple-based movement of Syndicate is a potentially positive new feature in the field of traversal mechanics, evolving the concept of using rails to travel between buildings the way we did in Jet Set Radio and Sunset Overdrive. However, the combat and vertical use of that grapple feel like a slightly sagging recreation of the fighting and grapple mechanics from Arkham Asylum, while rolling a carriage around London's cobblestone streets is the same thing as the driving from every open-world crime game. It wouldn't reflect on Ubisoft in such a ghastly way if they didn't also release two new open-world titles featuring third-person driving in the year before Syndicate's release: The Crew and Watch_Dogs. And whatever shiny new toys there may be in Syndicate's chest, I wish it would patch leaks in the series' existing elements before moving onto new ones.

For one thing, this is an experience dressed to the nines in stealth mechanics, but one that often won't reward you for using them. Some missions pay out bonus XP and currency if you can complete them without alerting police or Templars, and sometimes being discrete is how you avoid getting shredded to bits or wearied by fights with brutish enforcers. However, many more missions award you no such benefits and what does it say about the combat mechanics that it's a treat to not utilise them? You feel that you have the greatest mastery over Assassin's Creed's systems when you're successfully sneaky and so that's the behaviour the designers should be incentivising most. What's more, because stealth play requires more time, cautiousness, and precision than other flavours of play, players using it deserve a higher salary of XP and money, but in Syndicate and most of this series, they don't get it.

One sequence had me infiltrating the Tower of London to slay a marked woman inside. If there's anywhere that should require a deft hand from a player it's this place. The secondary objective for the Tower was to kill fewer than five guards, which might sound like it incentivises stealth, but most guards were in clear view of others meaning that knocking them out was virtually impossible. To catch my prey, I snuck up to the entry point of the tower, then ran inside, with about fifteen foes on my tail. I stabbed the boss, turned around, and ran back out, the guards still trailing behind me. It was stupid, unorganised play that didn't remotely give the impression of The Tower of London as an impenetrable fortress, but my strategy saved me time, came with no penalty, and fulfilled the secondary objective, so I used it. It's a typical example of how Syndicate often thrusts the pretence of stealth out the window, as does the series as a whole. Assassin's Creed tells you that you're an agent of a clandestine order that must keep itself out of the history books. However, the agents of that order can also get away with being seen murdering in broad daylight and leaving hills of corpses in the middle of the street.

And the problems of the game are not just in design but also implementation. Syndicate wears its glitches like badges of honour. Some of them are harmless enough that there's a case for them increasing the entertainment value of the game, but others can ruin whole missions. These were my personal highlights:

- One quest gave me an NPC to stalk who I inadvertently bumped into, which caused them to freeze in place and permanently stop walking.

- Once, even though my HP was full, I fell down dead for no apparent reason. My best guess is that I clipped through the level geometry.

- Once, the last object I needed to interact with to liberate an area spawned inside a haybale, making it unreachable.

- An NPC I was escorting clipped into the wall and died.

- An enemy intersected with the world geometry and started running in place.

- I now know a simple trick to make NPCs dive through the ground.

- Many instances of AI running into walls.

- A character who I was supposed to be able to speak to for a mission opportunity had no interaction prompt.

- A few times enemies punched me from off-screen.

- I've seen many instances of enemies running in circles.

- I completed a gang fight and had the victory cutscene play before it told me I had failed.

I'm worried that Assassin's Creed: Unity was broken in such a profound way that it overshadowed the technical fuzziness of Syndicate. By comparison, this game is the picture of rosy-cheeked health, but it should have been evaluated by how well it served its users rather than whether it was a step up from the hot mess of what Ubisoft released in 2014. What's more, Unity and Syndicate were not the only titles of their time which saw this company neglect quality control. From 2014-2015, Ubsioft released Assassin's Creed: Syndicate, Assassin's Creed: Unity, The Crew, and Watch_Dogs, all pieces of software that were clearly technically compromised to anyone who played them. One title that drops the ball is a mistake; four is a pattern, but a pattern that slipped past the sensors of most critics. And in Syndicate, even when the glitches are fairly benign, they keep you from suspending your disbelief and leave the game with a tacky feel. Overlapping with this is the issue that the game, the series even, is just janky.

"Jank" is one of those terms we use a lot but rarely define so let's unpack it. Various online dictionaries give a definition of "jank" in I.T. which boils down to "The phenomenon of poor UI design or hang times preventing smooth interaction with a program". Arguably, in gaming, it's also a term for any technical dysfunction of the software, but under either definition, Assassin's Creed remains a museum of jank. There are confusing GUI behaviours, such as how Eagle Vision highlights enemies in red but the interface also uses a red outline to communicate that an enemy is primed for assassination. It sometimes takes a second to see whether an enemy is ready for the chopping block or not which is displeasing when you're often up against the clock while stealthing. And for a game with assassination right in the title, it's frequently unreliable in letting you select enemies for the kill. Plenty of maps have guards stationed next to each other, requiring you to double-assassinate them, but when you sneak up behind them, you're lucky if it marks both of them for the attack. You often either have to reposition as they spot you, or unintentionally stab only one, alerting the other. A few other times, I've found myself sneaking up behind a sniper on a rooftop and hitting "X" only to have Evie or Jacob jump off the roof and slash at a character on the ground below.

This is all adjacent to a more pernicious aspect of Assassin's Creed's interface: The controls. Part of successful context-sensitive control design is ensuring that if you have more than one action assigned to one button, the player won't want to utilise any action bound to that button in the same context as any other action mapped to it. E.g. If you have a mechanic where the player needs to stuff dead bodies into carriages and drive them away to complete missions, but the B button is used for both "Carry Body" and "Enter Carriage", the player is likely to sometimes press B expecting it to perform one operation and get the other. Context-sensitive buttons are meant to strike a balance between encapsulating multiple functions and making it so that one action bound to a button doesn't block the player from accessing another action tied to it. Sometimes Assassin's Creed doesn't get that balance right.

Theoretically, every problem I've discussed up to now could be fixed. Maybe it wouldn't be practical for Ubisoft to do so, but we can imagine different design templates that would mitigate the issues in Syndicate and Assassin's Creed as a formula. But I also wonder if some of the jank that's stuck around since the first instalment is here not because of a poor implementation of the design but because it's inherent in the design. Platforming in Assassin's Creed has always been far too sticky and a little too unpredictable. Sometimes when you try to leap from a ledge, your character will hold fast to it, and sometimes when you try to hop from one platform to another, the game gets the wrong platform. It's an issue of controls so bear with me while we detour to some broader exploration of the purpose controls perform for a game.

We often talk about media such as film or novels having a "conversation" with their audience, but those media formats are only capable of monologuing. They may communicate to their audience, but the audience cannot directly communicate back and witness the piece altering its responses based on that communication. Ergo, there's no direct conversation. The only media that is capable of having a conversation with an audience is interactive media where the audience has some means of broadcasting emotions or intent, whether it's shouting at a stage or pressing a button on a controller. Video games, likely more than any other media, are capable of conversations; they communicate to us using GUIs, animations, and audio cues, and we talk back by manipulating an input device or input devices. The game uses its language to give a response to this input, we use our language to respond to that response, and the cycle continues until we turn it off.

Frequently, when games break down, it's this communication that's breaking down. If developers don't give us a fluent enough language to express what we want to do in the game or if the game's UI fails to communicate vital information then one side is missing critical data and so cannot respond in full to what the other party is telling them. The term "language" may make it sound like the communication methods of media must always express something highfalutin like "Life is suffering" or "Love is forever", but "I'd like to turn my car here" or "Your ammo is almost empty" are part of the typical language of games. It may be that Assassin's Creed is sometimes uncomfortable as a platformer because it doesn't always give us the vocabulary we'd need to talk about where we want to jump next.

You'll notice that unlike most platformers, Assassin's Creed doesn't let us directly control our movement when we jump and instead uses a lock-on feature wherein we point the control stick in the vague direction we want to move, hold down a trigger, and the game makes the jump for us. This system, like many lock-on systems, fails us when it locks onto the wrong targets, and this tends to happen because, if we're moving at speed, we don't have a very accurate way of telling the system where we want to be next. We'd have superior accuracy in our control if Assassin's Creed, like many other platformers, existed on a 2D plane, or if its levels weren't so multi-tiered. Unity gave the series some help in this department, allowing us to hold A or B when freerunning to signal to the game whether we want to jump up or down. However, there are plenty of ways navigation can still go wrong, and even under this system, the code sometimes second-guesses what level of elevation we want to change to.

So why doesn't Assassin's Creed, or for that matter, many other action-adventure titles, give us free movement when we jump? One answer is likely that the floaty free movement jump that platformers like Spyro or Crash Bandicoot employ is too cartoonish to fit Assassin's Creed's brand of pseudo-realistic fiction. In fact, the exaggerated, almost silly look of free movement jumps may be why many 90s platformers were cartoon-themed. The other problems are that it's much harder to use this kind of leap than it is an auto-jump feature and that it would break the flow of the free-running. If you thought landing on tiny platforms in Mega Man was hard, try doing it with an extra axis of movement, without having a clear side-on view of the platforms, and while moving continuously through the level.

Not every 3D game with platforming would be in need of an accurate auto-jump the way Assassin's Creed is; plenty use very wide platforms, so you're unlikely to jump for one and get another. However, Assassin's Creed wants realistic and detailed environments with high degrees of interaction. That means a lot of chimney stacks grouped close together or windows all the way down the front of a building. With so many potential platforms or handholds clustered so tightly, it's sometimes too much for the game to figure out which you want to jump to when you're gesturing in the direction of many of them at the same time. So you try to leap for one, and the game has you jump for another.

That explains that but what about those situations where you go to jump to an environmental feature, and the game leaves you stuck where you are like an insect on flypaper? There may be some semi-obtuse programming reason for why this happens, but I'd wager that some of the time, the design is trying to provide a handicap to keep you from making jumps you'll regret. Just as running to the edge of a roof often causes the game to auto-stop you so that you'd don't plummet to the street below, it may halt your movement at certain ledges and handholds in an effort to stop you careening somewhere you don't want to be. Ironically, this often prevents you from fluidly travelling to your target destination. Unlike the earlier issues we investigated, it's harder to see where the solutions to these problems might reside. In fact, there may be no solutions to some of them.

I try to use these articles to shed some light on how games are constructed and what their mechanics and narratives mean, and I'm aware that I've spent a lot of this article just listing off elements of Syndicate's design and engineering that feel phoned in. But for these formidably well-funded open-world games with enormous scopes, the list of problems is often also so enormous in scope that the only way to get a sense of how much a game like this buckles under player demands is to see the raw number of expectations it fails to fulfil. What sours me on a game like Syndicate is not that it makes quite a lot of gaffs in the average play session (many games do) but that it's still making so many after nine instalments and with an embarrassing amount of funding invested in it. When new series debut, we're willing to look past jank, glitches, and unconstructive side activities if there are enough bright, interesting ideas chaperoning them. However, the more titles you sculpt in that original game's image, the more worn out its once fresh concepts become and the less heavy lifting they do to excuse the experience's flaws. Case in point: Assassin's Creed 2007-2015.

Over this period, Assassin's Creed went through three phases:

2007-2009: The series' fundamentals are introduced and refined over Assassin's Creed I and II. At least by II, reception is glowing.

2010-2011: Ubisoft release Brotherhood and Revelations which are mechanically little more than reskins of II, much to the chagrin of the audience. Without original mechanics to distract from them, the game's functional weaknesses are more pronounced than ever.

2012-2015: Ubisoft comes out with III, Black Flag, Rogue, Unity, and Syndicate. They're entries that vary a fair bit in how much they want to go for a traditional vs. updated version of the series rulebook, but there's a general attempt not to let the series stagnate as it did from 2010-2011.

However, the process from 2012 onwards is one that's still going to create games that are good enough but never exceptional. Ubisoft cannot, under this development model, produce a title that feels breathtaking because even if every system a new entry introduces is perfect, the legacy issues in the game mean you'll never end up with every facet of it feeling polished. For all the rousing nautical fair, for all the opportunities to play head games with guards, for all the breezing between buildings on a zip line, you'll still find the play sputtering and groaning when you try to climb down a storefront or when you attempt to slide a knife into the back of an absent-minded watchman and your character jumps to the wrong handhold and alerts their enemies. Thanks for reading.

Log in to comment