Note: The following article contains major spoilers for Beyond: Two Souls, Fahrenheit: Indigo Prophecy, and Heavy Rain. It also makes mentions of sexual assault and suicide. If you are struggling with suicidal thoughts, contact a suicide prevention organisation near you. For those in the US, you can reach the Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 or find them online at suicidepreventionlifeline.org. If you are in the UK, you can call The Samaritans on 116123 or visit their website at samaritans.org.

If you were here the last time I threw a David Cage project onto the autopsy table, you'll remember me saying that we were never going to get the "Citizen Kane of video games" through developers attempting to copy acclaimed films. To recap, Heavy Rain, Cage's 2010 thriller released at the tail end of a heated debate over when, whether, and how we would get the breakthrough game that elevated the medium to the status of "art". The "Citizen Kane of video games" framing was a questionable inroad to these questions because the advancement of art forms has been a process of them developing their own unique strengths rather than copying any other form. And as critics like Doc Burford and Ian Bogost reminded us, there's only so far a game can resemble a motion picture anyway. Games lack the edits which underpin film, and the two media use the camera to wildly disparate ends.

Now, I want to take that concept a step further by saying that there never was a Citizen Kane of cinema. That is, there's a film called Citizen Kane, but it is not what pop film discussion often implies it is. Around the end of the 00s, many gamers invoked that work because they believed that it was the flawless intervention that turned films from weekend novelties into arresting portraits of the human condition. In this rickety facsimile of media theory, Citizen Kane constitutes a clear demarcation line between the period of history in which films weren't art and the period in which they were. Therefore, a Citizen Kane of video games would do the same for its relevant creative form.

In reality, the maturation of film required so many advancements, both tiny and large, in how they were lit, acted, written, scored, and shot that they could never have all come from one work. While I don't want to belittle Citizen Kane's outstanding contribution to its medium, it was standing on the shoulders of films that came immediately before. Likewise, films came after that developed ideas from Citizen Kane. You'll notice that we'd never try to talk about a Citizen Kane of music or painting because we understand that mastery of those media came together through a collective effort over a long period of time, and that's how film and games shook out too. Artistic evolution is not an event but a continuum.

I'm not going to make you suffer through any "Are games art?" chin-stroking here, but I think you'd agree that video games are, broadly speaking, more emotionally nuanced now than they were a decade ago. And we know that didn't happen because we found an Orson Welles of interactivity; we lay that advancement at the feet of many titles from Journey to Braid to This War of Mine. And even Citizen Kane wasn't seen as a game-changer upon its debut. It was a critical success, but a box office failure, that got archived away like so many others. It wasn't until the 50s, when various experts started to revisit the film's legacy, that its cultural value became apparent. You need some time after a piece of media releases to see whether its ideas propagate through the medium. It's only if they do that you can call it influential, so even if the Citizen Kane of video games could and had crash-landed in 2010, we wouldn't have known it.

At the time, the idea of this unicorn was appealing because it would have immediately and conclusively shot down critical attacks on games as a medium. That was never going to happen because of the collectively constructive nature of art. However, I think that nature makes art and entertainment far more interesting than if you could have a "Citizen Kane" of a format. Instead of a world in which there is only one work that contributed meaningfully to each medium, there is a vivid galaxy of creations that use their formats in varied and creative ways, each pushing the envelope across many separate axes. And while David Cage may have aspired to make a Citizen Kane for the PlayStation crowd, I think it's actually a boon to him that media doesn't mature that way. It takes the pressure off of Quantic Dream. They don't have to reshape all of games overnight to donate something to the format; they just have to add innovations that other developers can pick up and work with.

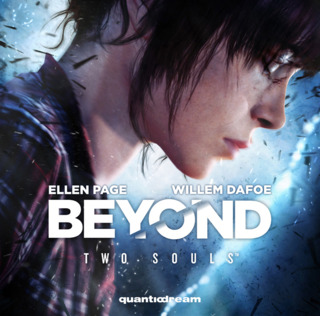

And even before release, something made Beyond stand out from the pack: the involvement of Hollywood's Elliot Page and Willem Dafoe. If Fahrenheit and Heavy Rain were Cage's attempts to adopt cinema's photography and storytelling, Beyond is his attempt to embrace the medium's actors. And they do make a difference. Page and Defoe were never the most venerated stars, but they were something more impressive: two professionals who realised distinct and highly personal performances without getting typecast. Page was known for playing coming-of-age characters in films such as Juno and Whip It, and girls wise beyond their years in pictures like Smart People and Hard Candy. Defoe was best known as the cackling villain in films like Streets of Fire and Once Upon a Time in Mexico but also had the talent in him for playing complex and tortured characters, as shown by his controversial portrayal of Jesus in The Last Temptation of Christ.

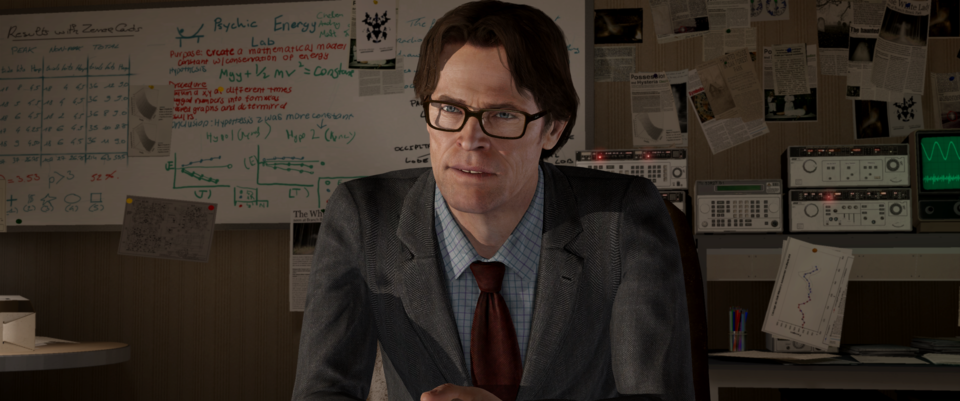

In Beyond, Page plays Jodie Holmes, a girl who has spent her life in contact with an invisible but sometimes troublesome entity called Aiden. This supernatural presence interrupts all stages of her life and causes her to be used and abused by adults in authority positions. Defoe takes on the role of Nathan Dawkins, a scientist who studies Jodie and with whom she forms a bond. Dawkins is controlling but compassionate while Jodie is within his care. Yet, his grief over his dead family eventually reduces him to a disillusioned monstrosity. Both these characters are born of their actors' histories: Page playing a teenager forced to grow up too fast and Defoe being the malevolent and troubled adult.

However, I'm not sure that before this, Page had ever played a character who suffered as much as Jodie, and on the set of Beyond, he contended with an exceptionally demanding production schedule. While most film scripts don't exceed 120 pages, Beyond's was around 2,000, and Elliot reports acting out 30 to 40 pages a day. It makes it all the more impressive that these two leads radiate emotion and show remarkable range.

Dawkins, as a guardian figure, has to be both loving and strict. And because the game is all about Jodie's development and giving the player plenty of chances to decide Jodie's reactions, Page has to ricochet between many conflicting feelings. The full nuance of these performances wouldn't have made it into the game if it weren't for Quantic Dream's sensitive motion capture equipment. Older mocap technology didn't always pick up minute expressions meaning actors had to "overact" to get their emotions across. As we see Cage explaining to Page in one behind-the-scenes clip, Beyond's sensors were up to recording in more detail, allowing for subtle emoting. Thus, Page and Defoe's performances can heighten a stimulating scene and buoy a sinking one.

But in the past, Cage's games weren't held back by low-quality acting. The most significant shortcomings of Heavy Rain, the game Quantic made before Beyond, were its unsolvable mystery, plot holes, neglected secondary characters, and misogyny. Fortunately, this 2013 thriller forgoes the mystery and focuses on one character, making some of those previous follies impossible. It also has a narrative that makes sense. However, its gender politics are all over the place. The game tells its story in non-chronological order, so I'm going to do the same.[1] I could reorganise these events into the order they happened, but the organisation of these chapters has an intractable impact on how we receive each of them, just as editing shapes a film.

The game's first true scene involves researchers placing a childhood Jodie in a testing environment and asking her to manipulate items in another room. Through the ghostly Aiden, she can read cards hidden from her view and even move objects. We then flash forward to Jodie's adulthood, in which she works as a spy. In this scene, she uses Aiden to read classified documents from the safe of a wealthy sheikh. In between these two events, Nathan takes Jodie to a party, but she struggles to fit in with the other children there. When they lock a claustrophobic Jodie in a closet, Aiden helps her break out and may take his revenge on the kids. We then get a scene of Jodie's parents taking her to Nathan's office for the first time and the doctor beginning to understand her incorporeal partner.

We see a teenage Jodie training at the CIA, which hones her into a physical and psychic soldier. Later, she finds herself running from the same agency, Aiden helping in her escape. The two eventually confront a SWAT team. In a chapter of Jodie's childhood, we see her alternately haunted and supported by Aiden. For a brief time, she plays happily with other kids of her own age until one of them bullies her, and Aiden chokes him. Jodie's father explodes at her, and that night she is dragged screaming from her bed by invisible beings. Prior to her CIA training, Jodie is awoken one night by Dawkins, who tells her the "condenser" for a local laboratory has gone haywire. This machine connects the world of the living to an afterlife called the "Infraworld", from which the entities who tormented a childhood Jodie originate. She and Aiden fight off the creatures and seal up the portal.

In the future, Jodie has been left homeless after fleeing the CIA. She falls into depression and nearly dies during a harsh winter but is saved by a man named Stan and taken into a small homeless community. She plays midwife to a teenager in the group, Tuesday, as Tuesday gives birth, and they spend the night in an abandoned building. The group awaken to find the building burning, and it's up to Jodie and Aiden to save them. Jodie is knocked unconscious either during this effort or subsequently by a street gang and spends months in a coma. Coming around to find the CIA still in hot pursuit, she jumps out of a hospital window.

We flash back to the first night Jodie spends sleeping in Dawkins' lab. Here too, the entities attack her, and Aiden may fend them off. We next see Jodie as a teenager, attempting to take a night out from the facility to meet friends. Dawkins forbids her and tries to drill into her that she can't have functional relationships with other people. She uses Aiden to take control of Nathan's assistant, Cole, and sneaks out to a bar. Unless she leaves immediately, a rabble of drunken men try to sexually assault her, and Aiden beats them back. We go back in time to see child Jodie's father telling her that he is relocating for his job and that she won't see her parents again. Aiden may attack her father in retaliation.

Back to Jodie's escape from the CIA, she wanders through the desert until she finds a Navajo family who takes her in. At night, a mysterious force attacks their ranch. Jodie discovers it is an evil spirit summoned by the family's ancestors to fight off colonists. She and Aiden work with the family to rid them of the being, creating a powerful connection between the family and Jodie before she moves onto her next rest stop. We see the day that the CIA recruits our protagonist. Ryan Clayton, the man who was with her at the sheikh's mansion, forces Dawkins to hand her over. In the future, Ryan visits Jodie's apartment for a date and professes his love to her. Aiden may ruin the date, pushing Ryan away, or Jodie may reject Ryan, feeling she's the wrong woman for him. Alternatively, Jodie can accept Ryan's advances. If the men at the bar tried to assault her, Jodie will be unable to sleep with Ryan due to traumatic flashbacks; otherwise, the two have sex.

In the future, we find why Jodie ran from the CIA. Ryan dispatched her into a Somalian warzone to sick Aiden on Sheik Charrief, a man Ryan tells her is a dictatorial warlord. Along the way, she befriends a child soldier, Salim. She uses Aiden to possess a guard at Charrief's compound, who guns down Charrief and his men, himself dying in the attack. Jodie soon learns that the man she manipulated was Salim's father and that Charrief was not a warlord but a democratically elected leader, something the CIA knew and lied to her about. She feels deeply betrayed by Ryan.

After her encounter with the Navajo, Jodie meets up with her old carer, Cole, who has found a probable biological mother for her, separate from the one she knew. She also learns from him that Nathan is now the head of the US government's Department of Paranormal Activities and that, working with the military, they have constructed another condenser. When Jodie finds her mother, she is in a vegetative state. Jodie speaks to her through Aiden and learns that the DPA took her child and drugged her into a dissociative trance to stop the knowledge of her exceptional baby from spreading. Jodie says goodbye to her mother, and the player must decide whether to put her out of her misery.

The CIA finally catches up with Jodie and arrests her and Cole. We see one night in Jodie's childhood where Nathan receives the news his wife and daughter have died in a car crash. As an adult, Jodie awakes in CIA custody, where Nathan has convinced them to go easy on her. He has struck a deal: if she helps the CIA shut down the condenser of Kazirstan, an enemy nation of the US, they will stop hunting her. The US military wishes to retain global supremacy by being the only country with a portal to the other side. Along with Ryan, Jodie infiltrates Kazirstan, destroys their condenser, and extracts alive.

From the time that Jodie wakes up in CIA custody to the time after their mission debriefing, she and Ryan negotiate their feelings for each other, and Jodie must decide whether she loves Ryan and wants to build a life with him. We flash back one last time to a night on which Nathan had dealt with his grief by drinking himself into a stupor. The child Jodie finds him and channels his spouse and daughter so that they can say their goodbyes. In the future, Nathan shows Jodie his new experiment: he has managed to trap his family in an agonising limbo between our dimension and the Infraworld. Despite Jodie's attempts at changing his mind, Nathan remains in denial that his science project is immoral.

The government renege on their agreement to release Jodie, and rather than let another psychic soldier roam free, prepare to mentally disable her, as they did her mother. At about the same time, Nathan releases the safeguards on the DPA's condenser, attempting to merge our world and the Infraworld so that he can be with his family. Aiden, Ryan, and Cole free Jodie and the four go to shut down the condenser, fighting off the entities that lash at them. As Jodie comes upon the heart of the apparatus, she runs into Nathan, who may die but can also try and fail to kill Jodie or successfully kill Ryan. The Infraworld entities may also kill Jodie, in which case the game ends with that dimension consuming our own, and Jodie left to wander the apocalyptic Earth as a spirit, forever contemplating her failures.

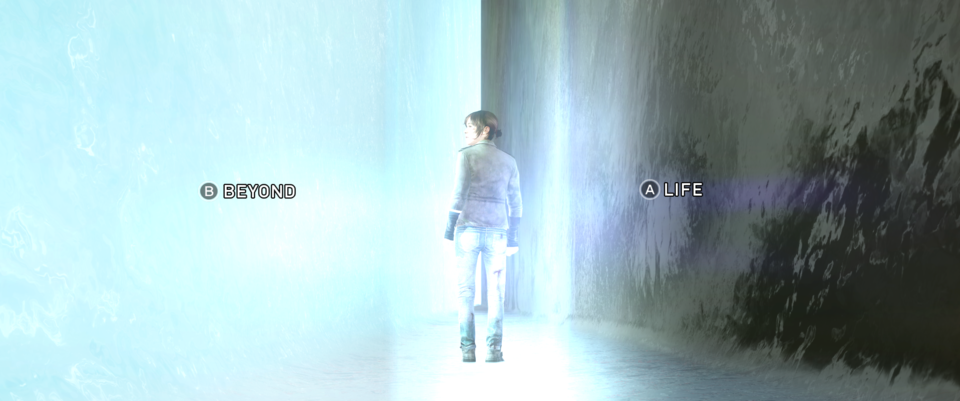

If Jodie lives, then ultimately, only she can enter the machine's nucleus, as Cole is injured or dead and Ryan is dead or has given up his protective equipment to save Jodie. If both Jodie and Ryan are alive, the two share a kiss before she ventures in. On the precipice of the Infraworld, Jodie learns that Aiden was her stillborn twin whose spirit lingered alongside her throughout her life. He passes over to the afterlife, and Jodie must decide whether to do the same. If she does, she experiences a natural paradise where she can exist "everywhere or nowhere" and can merge her soul with others. Our protagonist can see the past and all possible futures. If Ryan survived, he mourns her, and if Cole is alive, she will make her presence known to him. She communicates with and conveys a supernatural gift to Zoey, Tuesday's daughter, just as Aiden once did to her.

If Jodie chooses to stay alive, she spends a year of her life isolated from society in a cabin. This is her lowest point as she suffers the excruciating pain of Aiden's death. In the end, we must choose one of four possible futures for her. She may remain alone, believing that she can never live a normal life. She can move in with the former homeless who took her in, who now live in an apartment together. She can return to the Navajo family and form a relationship with the Native boy, Jay. She can also do the same with Ryan. In the "Alone", "Jay", and homeless endings, Aiden tells Jodie that he is still there, and in all endings, a larger conflict between the Infraworld and our world looms. Jodie, Zoey, or both, step up to fend off the entities and the credits roll.

David Cage's games aren't shy about coming from a father's perspective, and all his dad characters up to this point experienced the loss of loved ones. The traditional picture of a father in our society is a man who enacts violence to protect his family, and through doing so, earns a wife to serve him dutifully. This conception of the Dad worms its way into Cage's writing. In Fahrenheit, Lucas Kane's wife divorces him and takes his daughter, but if he can beat down his enemies and guard a certain godchild, he may save the world and win the affections of a new partner, Clara. In Heavy Rain, Ethan Mars loses one son in an accident, his wife divorces him, and a kidnapper takes his surviving son. If he risks his life and kills the kidnapper, he can win that son back. The female lead, and his potential partner, Madison, exists to soothe and heal him in this quest and may become his new wife. With Beyond, Quantic breaks from this fixation with telling traditional patriarchal stories, but its depiction of gender relations isn't squeaky clean by any means.

The second we see adult Jodie, she's wearing this revealing dress which feels like it has more to do with the assumed audience's desires than Jodie as a character. The game also gives far too much leeway to Ryan. He effectively kidnaps a vulnerable teenager from the closest thing she has to a stable home and forces her through backbreaking training so she can risk her life for an organisation that violently overthrows democratically-elected governments. If Jodie has a traumatic flashback, he abandons her. But the game spends so much time trying to set up a romance between these two, which it displays in no way as problematic. Even when we have Jodie reject Ryan's advances, she is still destined to kiss him in the condenser like that's somehow romantic.

At this point, I want to make it clear that I'm not a woman and so can't give you the definitive sign-off on whether this game is sexist or not. However, for all its faults and from my limited perspective, Beyond has a more humanising view of women because it's told from the perspective of a woman who must live for herself. Cage's previous games mostly granted agency and focus to male characters who the female characters lived for. Beyond also shows where this violent, patriarchal approach to fatherhood often makes a villain rather than a hero. At least for most of the game, Nathan is a sympathetic father figure, but his single-minded quest to reunite himself with his family threatens the people around him. His family's death causes palpable suffering for him, and he is capable of being a nurturing and emotionally available guardian for Jodie. Yet, in his inability to release his grip on his wife and daughter, he puts everyone in his vicinity in danger.

Aiden is also a man capable of being a protective figure in Jodie's life. Still, sometimes that looks like shooting magic missiles at otherworldly ghosts or hostile riot squads and sometimes that looks like choking children or making it impossible for Jodie to have an adult relationship. And Aiden's violence isn't just something we witness; it's something we get to play with, pushing and pulling on other people with mercy or wrath and telling a story of his development toward or away from protective patriarchy. We can make him a violent infant who matures into a more disciplined force as Jodie grows. We can make him start as passive, only to strike out at people as he sees Jodie hurt by them over and over. Or we can decide that Aiden sticks steadfastly to one philosophy through all his time in our world. If the question the game keeps asking us about Jodie is "What is she willing to do to survive?" then the question it keeps asking us about Aiden is "What is he willing to do to protect her?".

The Walking Dead and The Last of Us were two early 10s games that struck a chord with people because they showed emotionally advancing attitudes towards fathers. They talked about the benefits of loving a child beyond protectiveness and the consequences of exposing them to violence. That ran counter to games' prevailing concepts of masculinity. Beyond isn't as artful as either The Walking Dead or The Last of Us. However, it was part of that same generation of games tapping more progressive ideas about fatherhood. Where Fahrenheit and Heavy Rain's attitudes towards men felt outdated compared to how thoughtful those games were, overall, trying to be, Beyond shows a deep-set empathy by refraining from placing the father front and centre. Instead, seeing through a daughter's eyes.

This singular focus also digs Quantic out of the hole they landed themselves in in Heavy Rain. Instead of us getting four player characters, but the game only having time to flesh out two of them, we get one protagonist who lives a full life. Although, when zeroing in on that character's turmoil, Cage still has a penchant for laying it on thick. Rather than having a few tragedies befall them and then a lot of time for reflection on how those wounds may shape their life, the story leans too far towards a conga line of loss and debasement. Jodie is haunted by entities and haunted by Aiden and can't connect with other children and has to shut down the condenser and has her mentor struck down and is ripped away from him, and on it goes. After a certain point, I start thinking, "I get it, I feel bad for Jodie", and the additional disasters just feel like wasted time.

However, it's still more restrained in its melodrama than Heavy Rain was. It's not constantly raining with this oppressive, morose soundtrack colouring all the character interactions. In fact, Beyond is more disturbing than it is sorrowful. The uncanny is always about a distortion of the familiar: something we almost recognise, but that is that bit off. That uncanniness is here in the ethereal, warping Infraworld and Jodie's atypical union with her spirit brother. This story gets to the bottom of what it means to be haunted where many others don't. A lot of writers impart to us that being haunted means for someone unseen to be present, but don't get that part of what can be painful about it is the absence. Aiden doesn't just make Jodie's life difficult because he's always there, risking pushing away the people that Jodie might bind herself to, but also because he's not a full enough person to be a substitute for Jodie meeting physical people. He is just substantial enough for her to be alienated on both grounds.

The game is also disturbing in that disturbance is the opposite of comfort, and Jodie can never get comfortable because there is nowhere she is allowed to fit in. She's always the freak or the guinea pig or that useful piece of military equipment. Jodie is an outsider, and that's why it clicks in this way that feels so obvious when she finds a family in other outsiders: the homeless or the Navajo.

Speaking of the Navajo, their chapter does have an uncomfortable white saviour narrative. An unsurmountable evil plagues these native people until this white girl Mary Poppins her way into their lives. Within a few days, she has inspired their mute grandmother to speak, won access to their inner sanctum, and banished their ultimate adversary. But it works as a beat in the plot by being a surprising but coherent event that changes our notion of what might be possible for Jodie. I got so wrapped up with the commotion of her childhood neglect and eluding the CIA that I didn't think about the outside reality into which she might escape. And the encounters with the homeless people and the Navajo help ground the game. Jodie's affliction might be fantastical, but the idea of society hounding people until they're living on the desperate fringes is not. We can see it in our world because it's happened to people like Stan, the vagrant man, and Jay, the native boy. The desperation of the shunned is also why the "Death" and "Alone" endings suit Jodie so well.

In all but one case, Beyond gets its closing scenes right. It can be difficult for someone writing a branching narrative to make all the options feel like ones the protagonist would take. But Beyond has just the right measure of acceptance and exclusion for Jodie in the first two acts for it to feel like she could believably find a close-knit surrogate family or throw herself off the edge of our cosmos. The non-linear editing and sporadic pacing of the game capture how Jodie is often dragged kicking and screaming into the future. For her, the present is ephemeral, and the future is uncertain. This makes the ending feel transformative because, at last, Jodie can sit in one place for a sustained period through the support of other people who live volatile existences. And the game's morphing nature meaningfully informs what place we pick for her to sit in. We often talk as though a compelling interactive narrative is just one where our decisions affect the world, but there's also meaning in the world's state affecting our decisions.

In Beyond, your unique configuration of living and dead characters can influence your verdict on whether there's anything left for Jodie in the mortal dimension. On my original playthrough, I had her pass over to the other side, and that choice was primarily influenced by Nathan being dead and me not considering Ryan a viable romantic partner for her. In fact, it's Jodie's outsider status that makes the Ryan ending feel so inappropriate. What about this woman's experiences of being controlled and rejected by the status quo would make us believe that she would slip effortlessly into the arms of someone upholding it? That in a happy ending, she'd end up with an ex-CIA stooge?

Cage has always insisted that his games are pushing boundaries, and sometimes that's true. For example, Beyond's attitude towards the military divorces it from American culture's predominant beliefs about foreign policy. This game is rarely recognised for its anti-war stance, but at a time when Call of Duty: Black Ops was one of the most celebrated properties in popular media, Beyond was saying that the CIA are a threat to democracy, the US government exploit their soldiers, and that America is motivated by military dominance of the globe. But the game espouses that the CIA is bad while holding the contradictory position that the man it invented to represent the CIA is good. If Ryan loves Jodie that much, wouldn't he leave the organisation that abused her? Wouldn't he reflect on what he'd done to rip apart her life with Nathan and put her in harm's way?

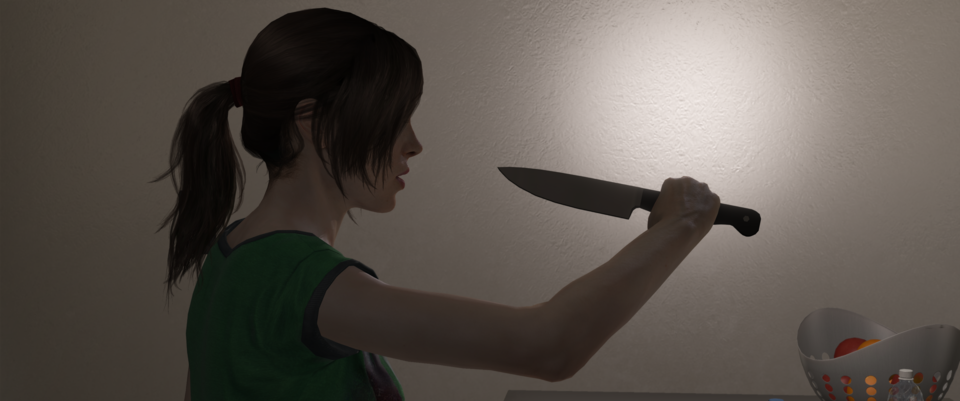

Beyond's insistence on pushing this relationship and smoothing over its toxic elements comes across as an attempt to stick as rigidly within patriarchal boundaries as possible. It overrides Jodie's agency and established character traits to get an ending where the guy kisses the girl and lives happily ever after. And this isn't the only time that it feels like Beyond blunts the excitement by returning to the familiar. The main advantage of the abstract and gestural mechanics that Cage's games use is that they allow us to play in areas that other games don't. When we're firing a gun or driving a car, Quantic's quick-time events can't match the depth and accuracy of feeling that dedicated action games can. But then those action games can't simulate the experience of shaving in the mirror or preparing dinner for your family, which Quantic games do.

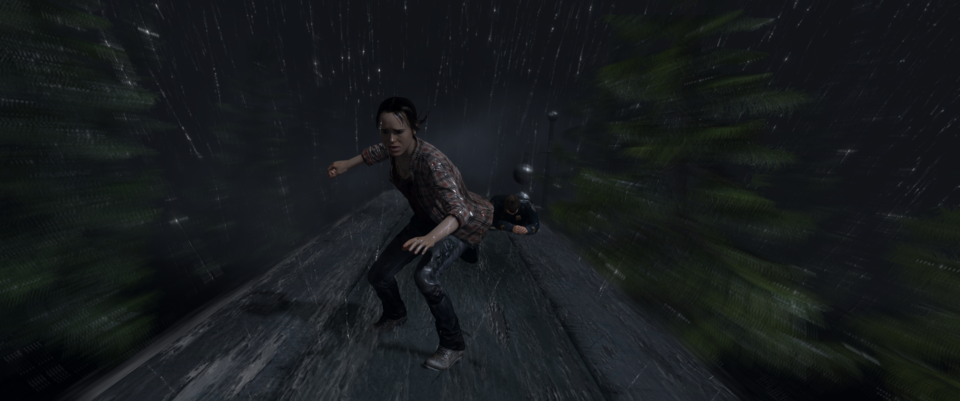

Sadly, Beyond waters down the complexity of those everyday QTEs and includes screens where there's only one correct object with which to interact. It gives us explorable 3D environments but then forces the camera in a "correct" direction as we try to get a bead on our surroundings. Worst of all, it's jam-packed with the action scenes it's so feeble at. This abundance is due to Jodie's job in the CIA and her subsequently having to fend them off. We gun down Somalian soldiers, attack the Kazirstanians, get into a motorcycle chase, etc. There are so many scenes in which we must wallop the Infraworld entities back where they came from, and they consist of performing the same three QTEs until you want to walk away from the console and do anything else.

The quick-time events also fail to realise Aiden as a spiritual being. In Heavy Rain and most of Beyond, the gestural minigames work because they're a simulation of some physical sensation we know from the real world or other media. The act of twiddling the thumbstick or alternating the bumpers isn't meaningful in itself, but if that rotation allows us to dress a wound or that button paddling allows us to swim from a sinking car, they take on meaning. They go from abstract inputs to representing a kind of recognisable contact between player and character or player and environment.

However, we don't have a mental model for the feelings of hijacking someone's mind or using psychokinesis to knock over a water bottle. So, Aiden's quick-time events are representational actions that don't represent anything. They're basic, arbitrary manipulations of the controller that feel empty because they're neither deep nor correspond to any physical motions that we'd recall.

The designers have accommodated for Beyond's increased focus on action in one way, but the implementation leaves a lot to be desired. In a twist on the quick-time event, the systems have us push the control stick in whatever direction Jodie is moving during the current shot. In comparison to Heavy Rain, Beyond features fewer fine manual tasks and more dramatic full-body lurches. So, it tries to find a ludo-cinematography that has us inhabit the protagonist's whole body rather than just their hands. But the timing on some of these prompts feel jarring, and it can be unclear what direction the designers want us to push the stick in during any one shot. If Jodie is moving down and right across the frame, is down a valid input? If Jodie's arms are moving upwards, but her legs are sliding to the right, are we meant to press right or press up?

In the manual tasks it sets us, Beyond plays to its weaknesses. It's not as keen at simulating acts of physical agility as a conventional action game, nor does it make as much time for life outside the action scenes, which is what its QTEs could bring to life. It all comes to a head in that final sequence as Jodie pushes her way into the black hole of the condenser. The scene should meet this dramatic plot point with equally dramatic play, but most of it is just holding forward on the control stick. As designers of game feel, Quantic backslid between Heavy Rain and Beyond. And the ups and downs of this title go beyond just the story they're telling and the mechanics they use to tell it. They're also profoundly interlinked with the structure that it employs.

Non-linear storytelling allows you to pepper up your narrative in ways that would be difficult in a chronological recounting. If the next scene in the character's life is not necessarily the one that would hit the right emotional note, you can jump forward or back in time to a scene that will. If you want to create intrigue, you can skip past a scene and make your audience wonder how a character got into a particular mess. Additionally, some audiences (I'm talking about me) find the process of decoding a non-linear plot to be a delightful puzzle. But that power comes at a price.

Earlier events in a story's chronology contextualise later ones, and as time goes on, the protagonist is likely to become more skilled and get into more trouble. So, when you're telling a story out of order, it's difficult to get it to make sense to the viewer and match the appropriate energy at all times. Remember, on the macro level, the intensity of any story should ramp up as it goes. Yet, in non-linear storytelling, a flashback can easily take us to a scene that's too placid, and a flash-forward can transport us to one that's overblown. And some audiences feel frustrated by the confusion that a non-linear narrative can provoke. You see both the light and dark side of non-linear storytelling in Beyond: Two Souls.

For example, Jodie's childhood consists of a lot of boredom and loneliness; it gives her early life an eerie detachedness. Cage could have written it so that Jodie gets into nasty scrapes even before her adolescence. However, an indispensable detail of Jodie and Aiden's character development is that they don't know how to channel their abilities until they go to Dawkins' lab and then the CIA. So, there's only so much peril she could reasonably have to defend herself from at this time. A quiet, defenceless childhood also explains why Jodie temporarily feels at home in the lab and the agency: they're the only places supporting her in applying her skills.

But if the game told its story in chronological order, the first couple of hours might be so subdued and homogenous that we switch off. On the flip side, after Jodie masters her powers, we get a lot of high-stress action scenes. These terrifying moments are what make Jodie's adulthood so harrowing. Yet, if Quantic told the story as it happened, these latter scenes would eventually overstimulate and bore the player. Because the game alternates childhood and adult events from Jodie's life, it can sustain a pattern of low and high-intensity moments that weaves throughout the whole experience. The first half is not all brake and the second half is not all gas. Instead, we get a non-linear narrative able to introduce each in an interleaving pattern.

The only mentionable exception to that alternation comes with the sixth and seventh chapters: Welcome to the CIA: an arduous training montage, and Hunted: the sequence in which Jodie flees the police. Playing the two back to back is exhausting and not always for the right reasons. Sometimes it's because the QTEs and combat don't stack up. Yet, this editing choice does effectively communicate how Jodie lacks a respite from her tribulations. She's tired of running and fighting but out of other options. Perhaps the best of the game's editing is in the juxtaposition of chapter fifteen and sixteen: Separation: in which Ryan steals Jodie away from Dawkins' outfit, and The Dinner: in which Jodie dates Ryan.

The lack of a segue between the chapters creates an engaging mystery: How does Jodie go from being poached by this man to wanting to be his partner? And remember, Aiden may threaten to ruin the date by harassing Ryan. If Cage had dropped this scene in before we got to know how Ryan derailed Jodie's childhood or if we'd had some time to cool off after that injury, we, as Aiden, might not be so hostile towards Ryan. By immediately following Separation with The Dinner, we get a scene in which Jodie has a reason to woo Ryan, but we have a motivation to sabotage her. You wouldn't achieve this effect outside of non-linear storytelling, and both the "Hunted" and "The Dinner" examples use the combination of interactivity and non-linear storytelling to create unique sensations or choices. Overall, having a plot that teleports us through time with little warning, and contains huge gaps, delivers disorientation that matches the precarity and discomfort of Jodie's life.

But then, I could talk about those same scenes with a less flattering inflexion. The sequences of rising through and then escaping from the CIA convey how beleaguered Jodie is by the end of it all. However, one of the reasons that many stories have these hard-boiled action sequences in the second act is that by then, the audience has hopefully built up an attachment to the protagonist and is invested in them coming out the other side unscathed. By pulling that second act action forward in time, the game threatens a character we haven't had optimal time to invest in.

And sure, at the time, the neighbouring Ryan scenes create interesting choices and conflicts, but the riddle of how Jodie grows so close to him is never solved. I'm not sure what it is about Ryan that Jodie would fall in love with; he's just there. Plus, while the non-linear timeline may be uncanny, it does make clear that a lot of our decisions in the game can't affect the future because the developer has already determined the contents of those scenes. What's more, there are a few folds in how the Beyond arranges the beats that weigh it down.

For example, from the start of the game to roughly the midpoint, the narrative slowly parcels out a childhood Jodie's experiences in the lab. In doing so, it avoids Fahrenheit's mistake of making supernatural elements central to the story but only introducing them at the last minute. But Beyond goes too far in the other direction. It needs to establish that Jodie has a connection to a non-corporeal entity called Aiden that can move objects and possess people, and that this scares other people. It has to teach us that otherworldly ghosts attack Jodie, that Aiden can fend them off, and that they're both studied in a lab for their powers. Where a decent film could communicate this information in a scene or two, it takes Beyond five chapters to get it across.[2] Therefore, when the game should be pulling into fifth gear, it's still stuck laying down these basics. The exposition wouldn't go down so rough if the dialogue in these scenes didn't oscillate between cliched child precociousness and Saharah dry scripting.

The other big structural issue is with Nathan's turn to the dark side. Nathan is one of the game's most prominent characters. We need time to digest what happens to him, and his heel turn would be more unexpected if the inciting incident and the clues that he'll go rotten are carefully sprinkled throughout the plot. Nathan's obsession with possessing his wife and child is nicely foreshadowed in the scene in which he tries to keep a teenage Jodie separated from friends her age. And his mindset in that scene is smartly seeded in the earlier scene in which a childhood Jodie is bullied at a party. But Nathan's fall from grace and reconstitution as an antagonist all happen within the game's last four chapters. And at the end, Nathan's decision to kill himself or shoot Jodie isn't given enough build-up. It's lost as the game hurriedly discards Nathan like a used tissue so it can fry the bigger fish of Jodie's arc and the Infraworld breach. It's typical for video games to rush their endings, but the reason this usually happens is that they're so action-centric that they have little time to develop or wrap up character journies. David Cage is making games that are more narrative-focused than action-focused, so I can't account for this.

Of course, the million-dollar question is: how does Beyond compare to Cage's other work? Is it better than Fahrenheit and Heavy Rain? Well, it's better than Fahrenheit (most things are better than Fahrenheit), but its quality relative to Heavy Rain is hazy. Rather than being better or worse, it's just different. Mechanically cruder, but on average, with fewer gaffs in its scripting. Nathan doesn't get the attention he deserves in the end, the Ryan-Jodie romance is forcefully contrived, and the game is half-asleep the whole time it's performing its setup. But it has a coherent plot, with a couple of truly brilliant moments, and a Cage protagonist that I feel drawn to more than any other. While the miseries of Ethan or Lucas could at times feel hammy, Beyond achieves its storytelling goal of ramming home how Aiden has been both a curse and a blessing for Jodie. And it carries the vicarious panic of being unable to get away from the people who would reject and manipulate her.

Yet, to contextualise Beyond's relative competence, we must return to the topic from the start of this article. Any medium during any era can be replete with tiny revolutions, so it was only a matter of time until Quantic Dream had competition in elevating entertainment software to the level of art. In 2010, Heavy Rain made some legitimate strides, but it was also guaranteed a certain amount of prestige due to the rarity of games with the potential to advance the form. When Sony released Beyond in 2013, they did it in a whole other frontier of video games. Between 2010 and 2013, we got such pivotal titles as The Walking Dead, Journey, Spec Ops: The Line, The Last of Us, Thirty Flights of Loving, The Stanley Parable, Gone Home, and Papers Please. The same period was also a breakout time for new media artists working in games like Anna Anthropy, Mattie Brice, Christine Love, Porpentine, and merritt k. These are games and people that challenged the medium's limits and our ideas about how virtual events could relate to the real world. Whatever else you might say about Beyond, it didn't do that.

A frustrating thing about the funding and attention heaped on Quantic Dream is that there are more obscure creators taking bigger risks that don't receive a fraction of the capital or column space. And I think it was around the time of Beyond that that first became clear. But I am glad I played it because I do believe there are storytelling achievements to see here. And there is a silver lining to this contrast between Quantic's games and the others intending to expand the artistry of the medium. If Cage and company got left behind, it's because of the breakneck pace of advancement at the time. In just three years, the format had transformed in a way that no one predicted. And while Beyond might just be a pretty good game, that it didn't stand up to its peers is proof of just how pioneering the frontrunners of the time were. Video games had had their coming of age. Thanks for reading.

Notes

- This article comments on the "Original" version of the game, not the "Remixed" one.

- Those chapters are, in order: Jodie's ESP test, her attending the party, her parents taking her to Nathan, the chapter in which the entities drag her out of bed, and her first night in the lab.

Log in to comment