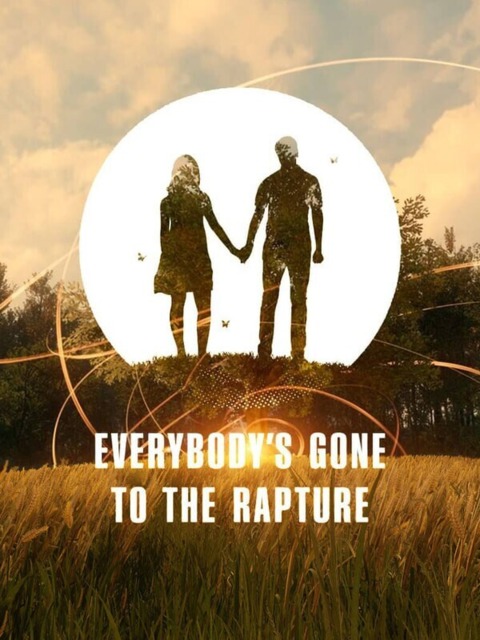

Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture Review – PS4

The air in the fictional Shropshire village of Yaughton, the setting for The Chinese Room’s latest offering Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture, is suffused with sadness. As you walk its picturesque yet empty lanes and streets melancholia lingers restlessly, desperately seeking a soul unto which it can impart its story before time renders it diffuse. Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture is an experience that could not exist in any time but now, yet equally is one that lies squarely within the millennia-old traditions of human story-telling.

“We leave nothing behind but our stories, and the hope that others will tell them”. These words from Iain Banks hounded my time in Yaughton, and more than two days after the credits rolled, I find myself still unable to shake the sentiment. In a period of profound uneasiness over the future of our species on this planet, The Chinese Room have asked us to explore the question as to what our legacy would be if we were to suddenly depart this plain. In the minds of designer Andrew Crawshaw and director Jessica Curry that legacy would be the idyllic rural English villages of their childhood memories.

It is on a glorious warm summer’s afternoon on the 6th June, 1984 that the story of this very British apocalypse unfolds. Something has happened at the observatory and the village finds itself faced with the unusual prospect of being under military quarantine. Played out in audio logs, the explanation as to why Yaughton, and presumably the entire world is so suddenly devoid of life is revealed piece by piece through radio broadcasts and telephone conversations found throughout the village and the surrounding countryside. Many of these snippets of information take time and patience to seek out, but ultimately how much of this you hear is dependent entirely on you and your desire to hear it. You may end your time in Yaughton none the wiser as to what has befallen its people, but in a game that constantly encourages you to look to the skies and use your imagination this should not be necessarily taken as a negative.

However, it is in the tales of its people that the real Yaughton story is told. Revealed little by little through the faint echoes of light found throughout the map, the final day of the villagers is acted out with a warmth and humanity only to be found in the trials and tribulations of the everyday. Despite the military occupancy and rumours of a conspiracy, the interactions between the villagers remain remarkably grounded and even mundane. Beyond one local woman remarking her surprise at there being a soldier with a rifle in Shropshire, the villagers seem at times barely concerned at what is happening around them. There are conversations that do touch upon the greater issues of race and religion, but on the whole the 6th June, 1984 is no different to any other pleasant summer’s day.

Yet, it is also within these quiet moments between the village folk that the greatest emotional impact of Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture is to be found. Be it the fraught and exhausted nerves of one mother too afraid to venture upstairs for fear of what she may find awaiting her, or the unquestioning belief by an elderly resident that the jets passing by overhead are there to rescue them from whatever evil has taken root within Yaughton, it is in these gentle scenes that the heart strings are pulled at the hardest. As you look once again to the beautiful night sky above, it is this time the words of Carl Sagan that feel the most apt: “In our obscurity – in all this vastness – there is no hint that help will come from elsewhere to save us from ourselves.”

The village of Yaughton itself is also drawn with an enviable clarity of vision. Not all of us may be lucky (or unlucky) enough to have been brought up in such idyllic surroundings, but the thick sense of nostalgia dripping from each mantelpiece and rotary dial is tangibly real (at least to those of us from the British isles). Much of this extended mise-en-scène (an occasional Commodore 64 or a menu board listing a bag of chips for just 10p for example), is incidental to the story itself and serves mainly as grounding for the period, but hidden throughout are also numerous other more telling props, placed deliberately with the purpose of adding extra contextual details to events. These props, be they a spilt pot of paint, or a trestle table in the meeting hall covered in half-drunk cups of tea, all lend a heartfelt, yet subtle poignancy to the experience that less thoughtful eyes may have missed.

All of this is executed with a beautifully keen aesthetic. For those of us not spoilt by the graphical capabilities of more powerful PCs, the village of Yaughton and its surrounding countryside, bathed in a Constable-esque summer’s glow, shine warmly and invitingly. From the perfectly rendered side path separating two neighbours’ gardens, adorned with all the vivid colours and flowers of late spring, to the lonely windmill perched atop the gently undulating hills of the Shropshire countryside, every element lovingly brings to mind the exact time and place. They say you should always write about what you know because it lends an intimacy that is wholly welcoming to others, and it is difficult to deny that train of thought when working your way through Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture.

When it finally came down to it, it seems that the end of the world in Yaughton was somewhat of a gentle experience. There was no looting, no mass violence, no roaming gangs of cannibals preying on the weak. There was a determined attempt by all to just carry on and to not make a fuss. The rapture arrived and people decided what was best was to have a cup of tea and put on a play of Peter Pan for the youngsters. It was British understatedness at its most heartfelt and at its very best.

When we depart this planet, what is it we will leave behind? What is it that would we choose to leave behind? Personally, I think we could do a lot worse than leave behind the village of Yaughton.

Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture

The Chinese Room

Robert Hill

Log in to comment