CONSIDER THE ELEPHANT

Elephants should be riddled with cancer.

I don't mean that as a knock against elephants. Whether they're helping Hannibal of Carthage invade Rome, providing impromptu heads for decapitated Hindu deities, or being electrocuted on film to amuse a public in love with the new technology of moving pictures, both history and myth show elephants to be noble, majestic creatures who should be given the benefit of the doubt even if they do see fit to trample the occasional tourist. Rather, when I say that elephants should have cancer, I mean it in a strictly biological sense.

With their vast lifespans and colossal bulk, elephants should be prime candidates for all sorts of cancer because cancer is the result of errors in cell replication, the likelihood of which increases with age and body mass. The fact that elephants remain exceptionally resistant to cancer, so much so that they can have natural lifespans lasting up to seventy years in the wild, is the result of an incredibly resilient, incredibly ruthless system built into their genes.

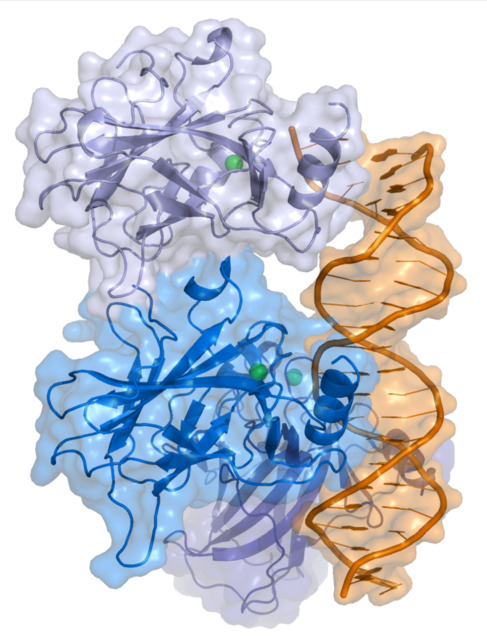

Almost all cells have natural self destruct mechanisms, a process biologists call 'apoptosis' that's absolutely vital to the survival of all multicellular organic life even if it sounds like the name of a boss from Metroid. On an average day between fifty and seventy billion of the cells in your body kill themselves for the good of the whole, a sacrifice that would be extremely noble if it was in any way voluntary and not a product of cold, biological calculation. Since the body of an average adult elephant has somewhere around eighty times the mass of an average adult human, they have eighty times the chance for cell replication to go wrong, for benign cells to mutate into something malignant and tumorous. This doesn't happen, because the rate of apoptosis in their bodies is also a great deal higher. There is a tumor suppressing gene called p53 (this, along with Uranus and Islets of Langerhans, is why scientists shouldn't be allowed to name their own discoveries) that appears in the human genome only once, but makes a whopping twenty appearances in elephant cells. This results in a quite literally elephantine rate of cell self-destruction that shames the paltry sixty billion daily average in the human body, a level of mind-boggling vigilance and merciless attrition resulting in one great, continuous purge of cells that allows elephants to live long, happy lives until a wealthy human shoots them to death for kicks.

Evolution is good at scaling up this way. It's easy to forget the same mechanism that dictated the course of life on this planet when the very first simple proteins emerged 3.7 billion years ago is still chugging along today without any fundamental alteration in how it works—only the scale has changed. It's also easy to forget that, despite the staggering expanse and diversity of life on Earth, there are many things evolution is very, very bad at.

BAD BRAINS

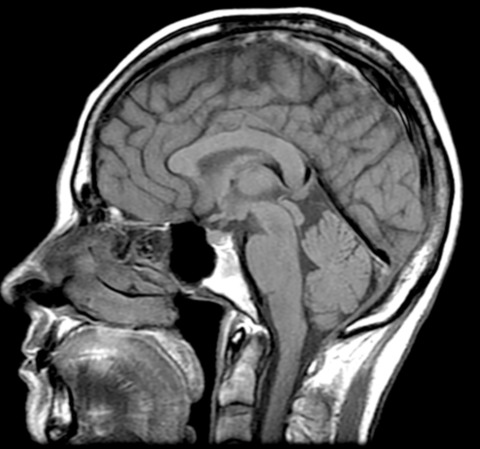

The human brain is the most complex instrument in the known Universe, which seems like a good thing until you realize the amount of things that can go wrong with it is commensurate with that complexity and, unlike how evolution has managed to accommodate the increased size and complexity of something like an elephant, the human brain has no special backup system to deal with the multitude of disastrous errors it's prone to.

There is nothing like apoptosis for neurons, there is only permanent brain damage. This is why something like traumatic brain injuries are such a scourge upon American Football players, since minor head trauma that would be insignificant on its own inflicts irreparable harm when repeated hundreds of times. There is no healing, the damage simply accrues like sand dissolving through an hourglass that can never be turned over.

This also holds true in cases of intentional brain damage. For example, in rare cases of extreme, treatment resistant epilepsy, there have been instances where people have voluntarily undergone surgery where their corpus callosum, the part of their brain that allows their right and left hemispheres to communicate, is severed. This procedure is not done so healthier tissue can take its place, the brain damage is permanent. Healing is impossible, and any adaptation to this new reality will not come from evolution, but from the will of the person whose brain was malfunctioning so badly the only way to improve it was to destroy a significant portion of it.

Like an oversized Swiss Army Knife, the human mind does a great many things, none of them particularly well. As an amateur brain enthusiast (I'd invite you join to our Discord but it's all cute animal photos and conspiracy theories at this point.) I've amassed a small collection of novel ways the brain can malfunction. There's Body Integrity Identity Disorder, which is the overwhelming sense that a part of your body, usually a limb, should not be there, inducing a mental turmoil so intense that sufferers often seek to have the offending limb amputated, even if they have to do it themselves. There's Cotard Delusion, in which a living person believes themselves to be dead. There's Echopraxia, the involuntary imitation of other people's movements.

Musical Ear Syndrome, a form of partial hearing loss that turns everyday sounds into music.

Riddoch Syndrome, a form of visual impairment where the sufferer can only see objects if they're moving.

Koro, where the sufferer is afflicted with the debilitating certainty that their genitals are retracting into their body.

Anton-Babinski Syndrome, where blind people believe they can see and can't be convinced otherwise.

Capgras Delusion, where the sufferer believes someone close to them has been replaced with an identical impostor.

Fatal Insomnia, which is, unfortunately, exactly what it sounds like.

The more I learn, the more amazing it becomes that we humans are capable of any productive functioning and rational action whatsoever, that we manage to be anything more than the sum of our damage, even if it often doesn't feel like it.

BROKEN LIKE ME

A common refrain among those noble souls attempting to comfort the mentally afflicted is “You are not your disease.”, a kind sentiment I've never been able to put much stock in. When your body is sick it is still just as much your body as when it's well, and believing there to be a pure essence to my mind that exists in a way that's somehow distinct from everything that's wrong with it strikes me as equally irrational as any clinical delusion. Still, mental illness certainly feels like something that's fundamentally apart from who and what we are, something we could effectively vanquish if only we could find a way to get our hands around its neck and squeeze; if only we could somehow render it tangible.

Whether it's writing a song about a lover who's done us wrong or fashioning a meme about a politician we loathe, humans are obsessed with externalizing their inner turmoil, since doing so grants us a degree of control over it, or at provides us with an illusion to that effect. The term 'art therapy' is a little redundant, since all art is therapy of a sort, whether it seeks to record truth, flatter a deity, hint at something abstract and intangible, or simply attract attention of any kind. The same holds true for video games, which have grown increasingly willing to address the topic of mental illness as the medium has (sort of) matured. Interactive art initially seems like the ideal way to reckon with such an intimate topic, yet efforts at depicting the human cost of severe mental illness in video games continue to prove decidedly mixed, which only makes it all the more incredible that a game in the Silent Hill series managed to accomplish it with depth and sympathy a lifetime ago.

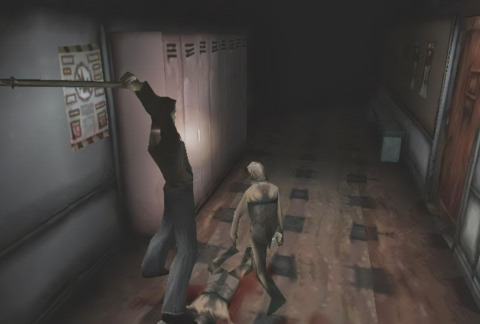

The Silent Hill franchise is, at its heart, a sort of mental illness power fantasy. If you've played a Silent Hill game hearing me refer the experience as a power fantasy may seem odd since you know the parade of milquetoast protagonists the games put you in control of move with all the grace and power of lead marionettes, and even doing something as simple as swinging a pipe to dispatch an enemy is a minor ordeal, requiring you to lash out with all the elegantly orchestrated violence of a rabid wombat.

Yes, the action of Silent Hill, if it can even be called that, is not rip and tear so much as flail and lurch, with your character constantly being no more than a few hits away from an anticlimactic grunt and a death that kicks you back to the last save. Instead, when I refer to the game as a power fantasy, I mean psychological power. The dream is one of being able to physically rip your neurosis out of your head, dragging it into the world of the material where it's exposed as an awkward, shambling thing that can be readily dispatched with some hearty pummeling from an everyday blunt instrument.

However, while the Silent Hill franchise would in time willingly adopt the moniker of Psychological Horror, intentionally positioning itself as the thinking and/or crazy man's horror video game, the first entry in the series is more horrifying than psychological.

The story of the first Silent Hill game is a flurry of interesting ideas awkwardly heaped together into a jumbled, semi-coherent blob. If the Silent Hill development team had possessed the kind of resources Konami allotted to another game of theirs released a scant three months prior called Metal Gear Solid: Tactical Espionage Action, the story might've made a little more sense since every character would've been given a fifteen to thirty minute monologue where they outlined their complex motivations, or at least explained why they don't have skin. Things are only further complicated by the story of the first Silent Hill game appearing deceptively simple at first, so straightforward it can be distilled to the lone sentence: “Evil cult tries to summon their god, to mixed results.” It's only when we look closer that things begin to spiral off into incoherence.

A subplot that's crucial to understanding the events of the first game is very easily missed, virtually guaranteeing that the player will get one of the extremely bleak bad endings on their first play through if they don't seek out a guide beforehand. Even if you do know what to look for, the story doesn't exactly take pains to make itself clear. Silent Hill 1's narrative is classic late 90's-early 2000's CD-ROM video game storytelling: a panoply of arcane lore scavenged from religious esoterica that's unceremoniously jumbled together into an evil cult powerful enough to keep a small New England resort town in its thrall. Add in several illicit drugs, including one that's a simple narcotic and another that that has the power to exorcise demons, and you have a story that spans multiple generations with body swaps, souls being divided in between different individuals, and multiple layers of reality being peeled back to expose a world of industrial ruin and raw viscera seething just beneath the surface of everyday life, a state of affairs that has the added benefit of allowing the developers to include twice as much content on the disc while having to only use enough extra storage space for a palette swap.

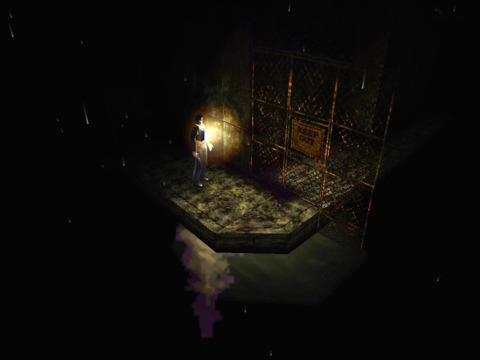

In retrospect it's easy to see how the mentally afflicted came to see their inner turmoil reflected in Silent Hill's gameplay. By creating a world that betrayed the player, with the bottom falling out of reality to strand them in an industrial hellscape that bore a superficial resemblance to the world they knew but regarded them with raw, predatory hostility, the developers stumbled onto a poignant allegory for a multitude of mental illness: anxiety, depression, schizophrenia, and all manner of delusions that distort everyday reality to imbue it with a vicious, hostile edge; however, in what would prove to be something of a trend, Silent Hill fans would have to wait to have the full potential of the series realized, though in this first case it would take only a scant two years and a single console generation.

There are good reasons why Silent Hill 2 retains its status as the series's high water mark despite the passage of lo these many years since its release in 2001. It benefits greatly by being divorced from the series's larger mythology, a ponderous cannon of obscure arcana that the developers wouldn't circle back to until Silent Hill 3. Silent Hill 2 allows the lore that preceded it, including the evil cult, black magic, human sacrifice, mysterious drugs, and tangled narrative of whose soul got split off into which form and deposited in what body when, to all fall to the wayside. Thus liberated, the designers are free to focus their attention on the deeply troubled characters they've populated Silent Hill 2 with, a loose cadre of tortured outsiders who are drawn to the town by the inexorable pull of their profound mental anguish.

The narrative of Silent Hill 2 makes no concrete attempt to explain why the town's reality is so hideously warped, merely hinting that the local citizenry have a rich history of tampering with the fabric of existence when they aren't running a quaint family-friendly tourist destination. Though the characters populating the game do pause at regular intervals to wonder what the hell is going on, the prospect of finding some way to undo the evil infesting the town and return it to normal never occurs to them. Though Konami's Silent Hill obviously draws a great deal of inspiration from Capcom's Resident Evil in terms of gameplay, the agency exercised by characters in Resident Evil is nowhere to be found in Silent Hill, where there is no evil corporation to expose and no secret underground laboratory to blow up.

The problems of Silent Hill take place on a different scale than the bioweapon outbreaks of Resident Evil, the extinct lizards running amok in Dino Crisis, or whatever the hell is going on in Parasite Eve. The characters of Silent Hill 2 already live demon-plagued lives before they set foot within the accursed town's fog-shrouded outskirts, all Silent Hill's occult power can do is materialize the forces already plaguing them. Even if it were possible to perform an exorcism on a municipal scale and effectively cleanse Silent Hill of the supernatural evil warping its reality, such a restoration of the natural order of things would do nothing to help the various mentally scarred individuals wandering its streets. They would still be just as psychologically tormented as before, the forces assaulting their minds no less real for being rendered once again intangible and unable to spit acid on them. The characters of Silent Hill 2 become increasingly aware of this as the game progresses and they experience a dawning awareness that, despite the faceless nurses, the limbless torsos, the hulking individual wielding a giant knife while sporting impractical headgear, and the many things made of meat that should not be made of meat infesting the town, all true horror comes from within, and the physical nightmare surrounding them couldn't exist if it wasn't being fed by steady stream of inner torment.

Nowhere is this more true than in the case of the most tragic character in Silent Hill 2. It's a title there's is no small amount of competition for given the almost universally dire mental state of the game's cast, but among the sad menagerie of lost souls populating the game, Angela Orosco has always stood out to me as a character who is uniquely notable for being especially worthy of compassion, even as she burns away before our eyes.

The Woman Who Wasn't There

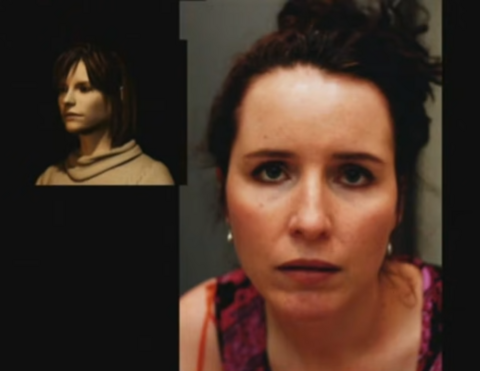

It's obvious that there's something profoundly off about Angela Orosco even before the savage intensity of her mental pain becomes apparent, an unsettling wrongness to her presence that has more do with some inexplicable casting choices on the part of the developers than the character herself.

According to official Silent Hill lore Angela Orosco is nineteen years old. The actress portraying her in Silent Hill 2 is in her late thirties. With neither of these prospective ages seeming to match the Angela Orosco presented to us, we're left to attempt to deduce her age based on how she behaves over the course of the game, but this only serves to confuse the issue even further. The abuse Angela Orosco has been subjected to has rendered her both prematurely aged and emotionally stunted, endowing her with a distorted personality that vacillates between vulnerability and hostility, cynicism and naiveté, apathy and rage, a spectrum of dysfunction further warped by a persistent self-loathing that seethes below the surface and occasionally erupts in hostile outbursts. The state of constant mental upheaval Angela exists in, combined with her being portrayed by a kind of acting that could be generously called exaggerated, results in a character who doesn't exhibit any behavior she can be consistently judged by. Attempting to pigeonhole Angela's state of mind is to play a sort of futile diagnostic Whac-A-Mole that will leave you struggling to reconcile behavior that contradicts itself multiple times over the course of a four minute cutscene.

Fortunately, we don't have to. Applying a specific label to a mental disorder is helpful in the early stages of treatment since it gives those trying to help some notion of what, precisely, they're dealing with, but labels can also be astoundingly useless when one attempts to move beyond the surface and reckon with the deep-seated neurosis of an individual who is, to paraphrase Tolstoy, fucked up in their own special way. Accordingly there are armchair diagnoses we can reasonably apply to Angela Orosco, but attaching a label like post-traumatic stress disorder or borderline personality disorder to her tells us nothing we don't already know; in practice such labels are barely more helpful to us than the antiquated diagnosis of hysteria that early psychiatrists so indiscriminately heaped upon female patents they'd judged to be driven mad by the emotional upheaval triggered by their wandering uteri.

Whatever her precise technical diagnosis, Angela Orosco is character who manages to effectively embody a form of dire, deep-rooted mental illness that's seldom seen in a form of pop culture like Silent Hill 2. Video games are, by nature, a goal-oriented medium, and as such tend to focus on rescuing characters. As a result they usually depict people being dragged out of the darkness, not drifting away into it. Yet despite her tragic story being so antithetical to the way video games typically function, the character of Angela Orosco doesn't just work within the narrative confines of Konami's second entry in the Silent Hill series, she transcends them. The result is a character who had such an impact on me that it's still resonating twenty years later, despite her appearing onscreen for a grand total of ten minutes over the course of a nine hour game. (Fifteen if you're 100%-ing it or as bad at puzzles as I am.)

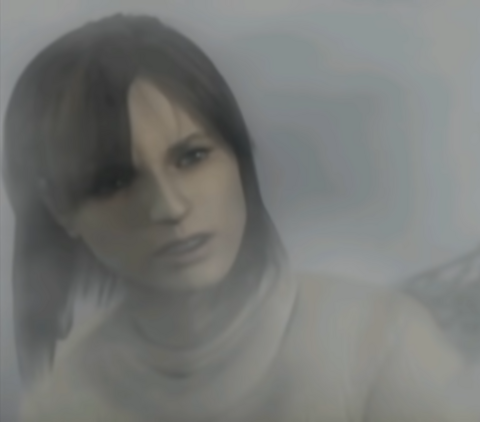

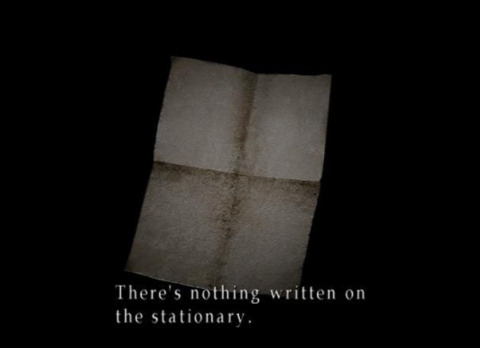

Silent Hill 2 opens by fading in on the game's protagonist James Sunderland gazing at his own reflection inside a highway rest stop men's room, a remote expression on his CGI face as if he's seeing himself for the first time or has somehow become unrecognizable to himself. The camera then cuts to a wide shot to reveal the bathroom surrounding him is bathed in a level of filth so dire you can practically smell it through the screen, every surface encrusted in layers of grime so dense they look like they could constitute their own geologic record.

It's a less than welcoming scene that sets a dual tone for the game, pairing introspection with revulsion so the two are intertwined from the very beginning; clearly communicating to us that, in the course of what is to follow, we will be made look inside ourselves, and we will not be comforted by what we see.

ENCOUNTER ONE — Lost

Angela is the first character we, as James, encounter after this inauspicious beginning. The interaction serves to fulfill some requisite horror tropes, with Angela embodying the classic role of the local native who delivers a warning to the intruding outsider, telling James that there's something wrong with the town of Silent Hill and he should stay away if he values his life. James then fulfills his own duty as the main character by disregarding Angela's sound advice and forging ahead anyway, an act that signals he's crossing the first narrative threshold by moving out of the world of the ordinary and into the world of story with its radically heightened, supernatural possibilities. It's easy to disregard this scene as merely one more recycled horror cliché among many but, as with so much of Silent Hill 2, there are some key distinctions that mark it out as special and reward further attention.

When we as James first encounter Angela Orosco she's staring at a tombstone, a motif the game will cycle back around to when James enters a complex of bewildering subterranean catacombs deep beneath the town of Silent Hill titled, appropriately enough, the Labyrinth, and encounters a cluster of readymade graves for characters who have yet to die, including one for Angela. It is just the most obvious of a litany of messages delivered to us over the course of the game indicating how well and truly damned Angela is, despite the unassuming impression she makes at first. The true, nightmarish extent of Angela's demons will become increasingly apparent over the course of the game, but in this initial encounter she is, if anything, conspicuously normal—at least by Silent Hill standards.

Angela responds to James's initial greeting with a brief outburst of terrified shock that's rendered slightly more plausible by the trademark Silent Hill fog that renders everything more than an arm's length away effectively invisible. After she calms down James tells her he's lost, which elicits a baffled response from Angela, who repeats the word back to him in a slow, skeptical echo, as if she doubts he knows what it really means. The implication of her reaction seems to be that the very fact that James is here means he can't be lost, his presence indicating that some intangible force in Silent Hill has decided he belongs. She's like the Mad Hatter telling Alice that if she wasn't mad, she wouldn't be here, though unlike the brazenly self-aware Hatter of Alice in Wonderland, this knowledge seems confined to Angela's subconscious. Though she's more aware of Silent Hill's danger than James, Angela is, like him, a stranger to herself, and can do nothing more than issue a warning James summarily ignores before allowing him to pass.

Despite establishing where we are and the danger we're facing, it's nothing anyone would judge as a particularly impactful scene, especially in a game where we regularly encounter a homicidal musclebound giant with a huge metal pyramid for a head having violent intercourse with monsters that appear to be crude amalgams of random deformed anatomy.

James Sunderland and Angela Orosco's paths only cross four times over the entirety of Silent Hill 2, with none of the encounters lasting more than four minutes. Just how few and brief these meetings are, coupled with the fact that Angela's story has nothing directly to do with the main character's, makes it easy to forget she even exists in between the rare instances when her's and James's paths happen to intersect. The relationship is rendered even more alienating by how, each new time we see Angela, her circumstances have dramatically changed.

It's a cycle that's already in full motion when James meets her for a second time later in the game, having now finally experienced enough of Silent Hill's unique form of hospitality to understand what she was trying to warn him about back in the cemetery. Angela derives no comfort from being thus validated. When we see her again within a monster-infested apartment building, inside a room that seemingly has no purpose other than to contain a giant mirror, the skittish but otherwise only slightly off woman James met on the outskirts of Silent Hill is gone, replaced with something I, on my first playthrough, had never seen before.

When I first played Silent Hill 2 in its release year of 2001, I had seen many things in the course of my deviant lifestyle choice of gamer. A monster the size of a mountain being shot with a cannon the size of a city. A nuclear armed walking tank stepping on an undead cyborg ninja. The same first three levels of Sonic The Hedgehog several hundred times. One thing I had never seen, right up to this very moment in Silent Hill 2, was a depressed person.

ENCOUNTER TWO — Afraid

When James meets Angela for the second time she's looking into a mirror just as he was when the game began. Unlike James, Angela isn't applying any degree of scrutiny to what she sees. As depicted with astonishing detail despite the limited budget, low resolution, and primitive state of CGI at the time, we can see that the look Angela regards the woman in the mirror with is one of bone-deep exhaustion and crushing apathy. When James announces his presence and Angela identifies herself to him for a second time, she speaks her name in the perfunctory tone of someone who's acknowledging a sorry but painfully obvious truth they've become woefully habituated to: My back still hurts. The car has broken down again. They passed me over for the promotion this year too. I am Angela.

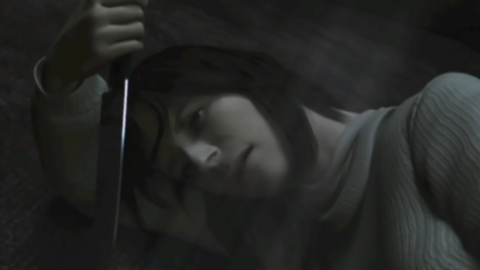

Unlike back in the cemetery when she instantly responded to James's appearance by recoiling in fear, this time Angela can't even bring herself to turn her head to look at James, who responds by crouching down to where she's sprawled on the floor and saying “Angela, okay. I don't know what you're planning, but there's always another way.” giving voice to his assumption that Angela is contemplating killing herself with the knife she's holding, which is quite the leap in logic on his part.

James now knows that the town is infested with hideous shambling monsters whose shapeless forms are motivated by nothing beyond a crude urge to inflict harm, which means Angela has every reason to carry a weapon with her. Even if the town of Silent Hill wasn't a hellscape populated by abominations of demented viscera, holding a knife and using it against yourself are two very different things, and it makes no sense for James to assume one will invariably lead to the other. Taken at face value it's a reaction that defies interpretation, but if we consider it in the larger context of Silent Hill 2, it makes a little more sense.

James recognizes his own self-destructive impulses in Angela. Angela sees the same thing in James and responds to his expression of concern with a wearily skeptical “Really?” followed by “But you're the same as me. It's easier just to run. Besides, it's what we deserve.” James protests, saying “No, I'm not like you.”, which is a lie. James is indeed suicidal, so much so that one of Silent Hill 2's less uplifting endings has him drowning himself. He already directly expressed his indifference to his own survival back in the cemetery when he told Angela he didn't really care if Silent Hill was dangerous.

Though we don't know it yet, in time the game will show us that Angela and James have both killed people, and are both in denial about it. It will eventually be revealed that the knife Angela is holding is the same knife she killed her father and brother with after a lifetime of physical, mental, and sexual abuse, imbuing it with a significance James seems to instinctively recognize, even if he doesn't understand why.

The emotionally walking wounded can have a wicked tendency to find one another. The recognition often isn't conscious, and can have dire consequences as each individual's fundamental damage only becomes apparent over time, at which point both participants are already mired in a swamp of toxic codependence. In Angela, James can see the sick parts of himself reflected back at him, even if he can't consciously admit it. Angela is also in a sort of denial, but unlike James, her denial has given her no respite from her guilt and all the rage, despair, and self-loathing that comes with it, regardless of whether she deserves it or not.

A detail that's easy to miss is, when we as James enter the room and first encounter Angela lying on the floor, she isn't just looking into the mirror, she's also looking into the reflective chrome surface of the knife she's stuck into the floor. We can't see what Angela is seeing in that moment, (given the state of CGI at the time and the budget the developers were working with, crafting such a finely detailed scene was impractical) but we can safely assume the image the knife reflects back at her is a distorted one, a twisted grotesque that may yet seem more real to her than the unassuming woman in the mirror. Angela can't see past her crime and thus can't see herself, the person who was hurt and hurt and hurt until they were pushed beyond the limits of human endurance, the person who deserves sympathy instead of hate.

Angela's responses to James's hesitant overtures in this scene run the emotional gamut, beginning with a depression so crushing she can barely bring herself to respond to him followed by weary skepticism, bemused contempt, severe paranoia, even more severe anxiety, then finally utter terror—and always, like valleys between the peaks, she reverts to the mean of abject depression, at one point going so far as to utter the eternal mantra of the clinically depressed: “I'm so tired.”

The second meeting of James and Angela ends in a paroxysm of fear and shame. Angela offers the knife she's holding to James, saying she doesn't know what she'd do if she kept it. When James reaches out to take it Angela cries out in fear and points the knife at him only to just as spontaneously apologize, saying “I've been bad.” as she drops the knife on a table and retreats to parts unknown, vanishing in an outburst of self-reproach.

It's important to point out that this is just the latest in a barrage of apologies Angela has directed at James. In the course of a meeting that lasts three minutes and forty seconds, Angela says “I'm sorry” to James four times, a vulgar excess of contrition usually reserved for religious penitents. As she apologizes again and again, it becomes increasingly clear that Angela is not apologizing for anything she's done; she's apologizing for being alive, for burdening the world with her continued, repugnant existence.

The traumatic, dehumanizing abuse Angela suffered at the hands of her father and brother has forced a lifetime's worth of anger on her, but unlike Silent Hill 2's other tertiary character, the much more homicidally inclined Eddie Dombrowski, Angela doesn't take her anger out on other people but directs it inward toward herself, a deranged coping mechanism where, by blaming herself for what was done to her, she was once able to feel some small measure of control over the situation, no matter how absurd or virulent. It's a mentality that may have helped Angela survive while she was at the mercy of her abusers, but by the time of Silent Hill 2 it has not only outlived its usefulness, it is eating her alive.

Yet even this scene only hints at the full extent of the mental torment afflicting Angela, the true scope of which will only be revealed to us much later, when we've descended to the absolute nadir of Silent Hill's dark imaginings.

ENCOUNTER THREE — Sick

Silent Hill 2's attempt to shape Angela Orosco's experience into a coherent story is far from perfect, as evidenced by the fact that, the first time I played through the game, I had completely forgotten she existed when I encountered her for the third time, and had no idea what was happening when I did.

I can't really fault the developers, who by the standards of the time were cramming a massive amount of storytelling into a very small package, but it's also true that Silent Hill as a franchise tends to value its sense of atmosphere over narrative coherence. This made it an early beneficiary of internet fan culture as devotees of the series were forced to pool their wisdom in a collective effort to discern what the hell was going on. It's an air of mystery that's good for attracting and sustaining the attention of hardcore fans, but it also does a disservice to characters like Angela Orosco, whose fates can be obscured within a haze of narrative ambiguity when they deserve our full attention. James's third encounter with Angela is already violently surreal enough on its own without seeming to appear out of thin air.

There's a massive amount of gameplay between the second encounter with Angela and the third, during which time the world presented to us has descended to unprecedented levels of existential depravity, and reality has seemingly been shattered beyond all repair. With nothing more than a newspaper article about the murder of Angela Orosco's father to remind us she exists, a note that itself has much of its text obscured by blood, the game does a poor job of preparing us to comprehend the scene the third encounter with Angela presents to us; though it's admittedly difficult to imagine how anyone could possibly be ready to witness what follows.

James's third encounter with Angela is not intended to merely horrify the player but is deliberately calculated to disturb and even literally sicken them. It's no doubt more difficult for younger readers accustomed to at least one atrocity being purposely inserted into every Call of Duty game to appreciate this, but there was a time when major video games simply didn't do that—at least not on purpose. Not only did Silent Hill 2 cross that final threshold, just as importantly, the recipient of the trauma it depicted was not some random, disposable NPC but a thinking, feeling person, one whose suffering is no less genuine for how unreal the world around her has become.

The third encounter begins with a cry in the dark, the sound of Angela begging her father not to hurt her. James follows her screams into a room unlike anything else in Silent Hill 2. Here we again find Angela on the ground, only now she's hunched in a sitting position and being menaced by a monster that... defies easy description. Like so many other monsters in Silent Hill, the thing threatening Angela is not really one thing, but rather several incompatible things joined together. It's an effect where unnatural bodies are rendered even more disturbing by unnatural movements as monsters twist and writhe, contorting themselves in painful, futile attempts to somehow accommodate anatomy that exists in defiance of all reason and logic. The most iconic manifestation of this design philosophy is of course Pyramid Head, or Red Pyramid Thing if you're going by the canonical name, but its most intense expression is the thing that menaces Angela during the third encounter, a creature that bears the official name of Abstract Daddy, which, like every other enemy name in Silent Hill, seems like a placeholder that stuck.

If Silent Hill 2's designers ever take their vision too far it is here, where they willingly sacrifice coherence in the name of dramatic effect. The result is that the Abstract Daddy monster is one thing that is actually three things, one of which may itself be two things.

Abstract Daddy is a bed with crude arms and legs, a large phallus with a human mouth at its terminus, and a bulging, vaguely humanoid mass slouched atop the bed that maintains a persistent thrusting motion like that of someone engaged in copulation beneath an unspeakably soiled sheet. It's impossible to tell for certain if there's another figure below the writhing humanesque form, there are hints of shapes that might be a pair of legs, but there's no way to be sure. You're welcome to look for yourself and draw your own conclusions, but I advise against viewing Abstract Daddy for any extended period of time. I'm not saying just looking at it is going to have a detrimental effect on your mental health, but it certainly can't help.

Abstract Daddy is an incoherent thing, a mass of symbols heaped atop symbols until it collapses under the weight of its own significance. Its mere existence is so abhorrent having it physically accost James seems almost redundant since the impression it makes is hideous enough to motivate the player to kill it on principle, regardless of whether or not it poses a tangible threat.

Its very crudeness is an important aspect of what makes it so horrifying, its nonsensical form giving awful shape to the tangled mass of toxic, contradictory emotions and memories survivors of abuse are burdened with. In its formlessness Abstract Daddy looks like what would result if an abused child was asked to draw what happened to them, something that's so crude as to be incomprehensible yet somehow still manages to disturb, affecting us on a primal level that bypasses conscious understanding.

As Angela Orosco told us at the beginning of the game, she came to the town of Silent Hill in search of her mother. She doesn't say specifically why she's seeking her out during the first encounter in the cemetery, but when James says that he's searching for someone very important to him, someone he'd do anything to be with again, Angela responds “Me too.” She says she's looking for her mama, than immediately corrects herself, saying “I mean my mother.” It's the first and last time she'll bother correcting herself in this way, reverting to using the more childish 'mama' for the rest of the Silent Hill 2.

The game will never explicitly tell us why Angela is looking for her mother, or even why she came to Silent Hill to look for her, since there's nothing to indicate her mother ever lived in Silent Hill in the first place. Instead it seems as if the town attracted Angela via the same intangible, supernatural means it draws other emotionally damaged individuals to it. James Sunderland also seems to have been attracted to the town by his own mental illness since, if we at look the letter he received from his deceased wife summoning him to Silent Hill during the later portion of the game, it's first revealed to be blank, then disappears entirely. The town itself seems to feed on the mental anguish of the broken individuals it summons and isn't above torturing them to get what it wants, even if it does also seem to abide by its own, profoundly deranged sense of sadistic justice.

In the case of both James Sunderland and Angela Orosco, it's effectively impossible to tell where their search for a specific individual ends and their search for some form of relief from their mental agony begins. Angela is literally searching for her mother, but she's also searching for everything her mother has come to represent in her tormented mind: the childhood that was ripped away from her, and the only love she ever received that wasn't totally contaminated by merciless violence. Silent Hill gives her the complete opposite.

Abstract Daddy is the hideous embodiment of every physical and mental evil that has been visited upon Angela by her father and brother. If she was in a better place emotionally Angela may have been capable of experiencing some catharsis by killing Abstract Daddy herself, thus independently destroying the living embodiment of her pain, but even if she still had the knife she surrendered to James during their prior meeting her mind is in no state to fight back, and she can only beg for mercy until we, as James, arrive and dispatch the monstrosity ourselves.

The room the third encounter takes place in represents body horror at Silent Hill 2's most intense. The interior resembles flesh the putrescent color of sallow, jaundiced skin, itself shaded in the diseased hues of bruises and scar tissue. The walls are perforated with circular recesses containing endlessly thrusting pistons in a none-too-subtle portrayal of human sex at its most mechanical and dehumanized.

Through the duration of James's fight with Abstract Daddy Angela remains huddled on the floor, appearing vanishingly small amid the room's vastly repulsive interior. It's only after the fight has concluded and Abstract Daddy slouches defeated to the floor that Angela is able to rouse herself and finally, finally give vent to the rage inside inside her, first screaming as she delivers a series of kicks to the monster, then hefting up a very conveniently paced television and bringing its full weight crashing down on a still perversely living enemy, finally seeming to kill it once and for all. James then immediately tells her to relax, which in a game full of people dispensing ill-timed and useless advice to one another, still manages to rank among the worst. Angela responds with justified outrage expressed via the awkwardly worded outburst “Don't order me around!” James tries to reassure her, but Angela's hostility only intensifies, and she accuses him of only being nice to her in order to garner sexual favors. James's denials do nothing to quench her fury, but Angela's anger can't be sustained, and implodes as spontaneously as it appeared.

Angela tells James to just be honest about what she knows he really wants, dissolving into sobs as she collapses back to the ground and says he could just assault her like her father did. The forces tearing at Angela's mind are made hideously manifest as she begins to retch, though she's unable to actually vomit up anything. James reaches out to touch Angela's shoulder in a misguided attempt at consoling her and she slaps his hand away before he can make contact, crying out “Don't touch me! You make me sick!”

Of course, it isn't James that's making her sick, at least not directly.

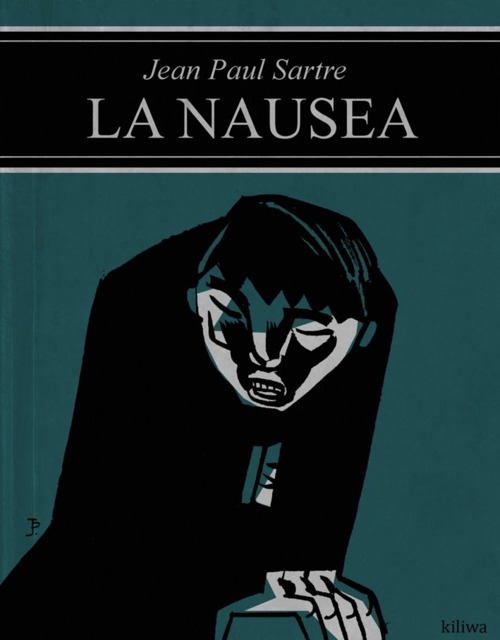

Physical illness as a metaphor for mental suffering has existed as long as human beings have been telling each other stories, but nausea specifically gained special symbolic significance in the twentieth century with the rise of existential philosophy and its focus on the many quandaries and paradoxes intrinsic to the human condition. This change was significant because it was a departure from illnesses that could be easily romanticized such as tuberculosis (consumption) epilepsy (the sacred disease) and fevers to something that was more fundamentally ugly, undignified, and representative of how we as humans must submit to the involuntary whims of our bodies, representing a violent uncontrolled outburst that immediately dispels all our pretenses to human exceptionalism, reminding us that we are not only mere flesh and blood but other, more disgusting substances we prefer not to think about.

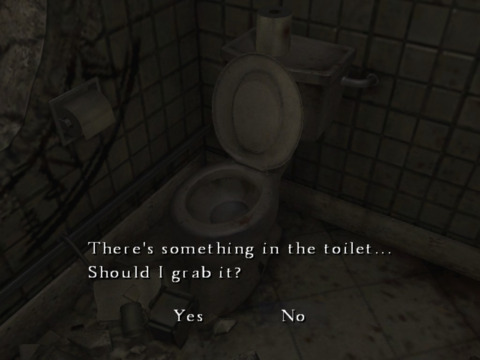

At this point in the game Silent Hill 2 has already liberally indulged in using the act of vomiting to signal character traits. The entirety of James's first encounter with the game's other tertiary character Eddie Dombrowski consists of Eddie colorfully regurgitating into a toilet. Unlike Angelia his emesis is quite productive, as illustrated by the barrage of wet sound effects the player is treated to over the course of the exchange.

It's tempting to hope that Angela could somehow physically expel the trauma inside her, but as the game demonstrates with Eddie Dombrowski, who remains a homicidal maniac despite his copious purging, it isn't that simple.

Unlike Angela, by the time we encounter Eddie he has already willingly relinquished any claim to being a victim and given himself over entirely to his violent impulses, killing every person he senses a hint of disrespect from, a trait his paranoid mind eventually perceives in everyone. Angela Orosco's mental agony is even more intense than Eddie's, but unlike him she holds all her pain inside herself. Even when she manages to express her anger she redirects it at herself immediately, superciliously inviting James to hurt her the same way everyone else in her life has, unable to imagine anyone regarding her as anything other than a thing to be used and discarded. Even this is a kind of deranged coping mechanism: Seeing herself as a victim worthy of compassion would force Angela to come face to face with the sheer magnitude of the evil that was done to her. By blaming herself Angela is, in a sick way, protecting herself from a truth that's too horrible to contemplate, even if a significant part of herself knows where the blame truly lies.

Disgust is a key theme in Silent Hill 2 which, let us not forget, opens in a roadside bathroom, a location that, in terms of pure squalor, ranks below only slaughterhouses, outhouses, and your average fast food kitchen. (Carl's Jr. is the exception, they run a tight ship. Hardee's, however, is soiled beyond imagining.) The bathroom was the first room modeled by Silent Hill 2's art director and was deliberately used as a template for the rest of the game's design philosophy, something the environmental artists could refer back to when considering the mood they intended to cultivate.

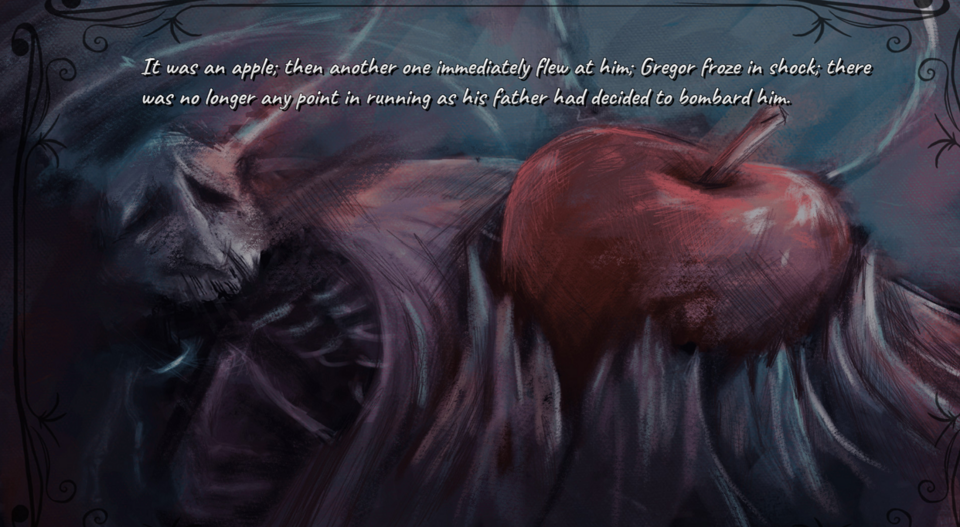

The narration that opens the game comes from the letter supposedly written to James by his deceased wife Mary. It begins “In my restless dreams, I see that town. Silent Hill.” The line is a direct reference to the novella The Metamorphosis by Franz Kafka which, depending on your translation, opens with the sentence: “As Gregor Samsa awoke one morning from restless dreams he found himself transformed in his bed into a gigantic insect.” (The word for 'restless', 'unruhigen' in German, has been variously translated as uneasy, unsettling, troubled, and agitated.)

The Metamorphosis, in brief, is the story of a man who spontaneously transforms into a giant insect for no tangible reason. He hides in his room from the world and his increasingly resentful family, eating garbage and retreating under the sofa until he is gravely wounded by a piece of fruit thrown with deadly accuracy, and ultimately starves to death. Like everything else by Kafka it's more fun to theorize about than actually read, though I always thought it would make a good multi-camera sitcom; like ALF but with actual jokes.

There's much disagreement on what The Metamorphosis truly means, but one popular school of thought interprets it in terms of existential despair, holding that Gregor Samsa's spontaneous and inexplicable transformation into something unbearably repulsive is a vivid illustration of the human condition, something we are all faced with when we are confronted with aspects of our lives and ourselves that are repugnant to us, be it mental illness or just the creeping suspicion that we are nothing more than meat with a high opinion of itself.

Such is the implicit accusation of all body horror, and Silent Hill 2 is no exception. In the room containing Abstract Daddy the game's themes of disgust and dehumanization reach their abject extreme, and we are finally able to behold the full scope of Angela Orosco's suffering in its full, hideous intensity.

Pretty much anything that followed such a savage barrage of human misery would be an anticlimax, but Silent Hill 2 does itself no favors by ending the cutscene with Angela instantly recovering from her mental and physical breakdown, delivering some exposition, and unceremoniously leaving for parts unknown. She twists the proverbial knife one last time, telling James she knows what he did to his wife. At this point in the game her declaration means little to us, the player, since we ourselves don't know what James did to his wife. It's only when James and Angela meet for the fourth and final time that the full scope of who Angela Orosco and James Sunderland are and what they've done will be apparent to us, though it isn't the revelations themselves that are important so much as the way the game chooses to deal with them, denying us easy answers in a scene whose final poignancy transcends cliché and turns the character of Angela Orosco into something truly exceptional that continues to resonate with me to this day.

ENCOUNTER FOUR — Love and Hell

If it wasn't for the stairway scene, I wouldn't be writing this and you'd probably be reading something begging you to care about Legacy of Kain: Soul Reaver right now. (It was the first time I heard someone use the word 'altruistic' in a sentence! Also the time traveling ghoul/vampire was neat.) Its faults notwithstanding, the power Silent Hill 2 manages to imbue Angela's character arc with over the course of three brief scenes is incredible. Still, all that judiciously cultivated empathy and uncanniness could have been squandered if the developers failed to capitalize on it in her final meeting with James. Instead Silent Hill 2 presents a closing scene that gives full weight to everything we now know Angela Orosco has been through, even as it's colored by the fresh revelation that James killed his wife after three years of watching her endure a chronic, intractable illness. In doing so the fourth encounter manages to overcome the storytelling limitations intrinsic to the medium of video games at the time and create a full character who feels achingly, indelibly real, her ultimate fate cutting to the bone even as the main narrative accelerates to its conclusion and one of four different endings.

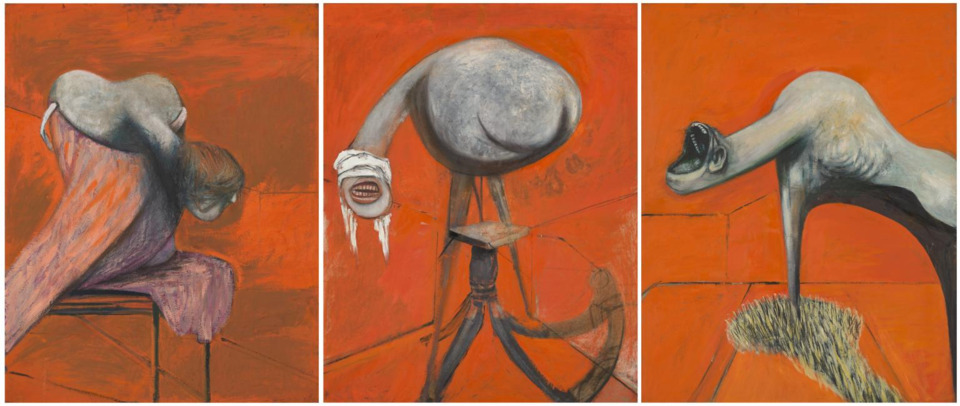

The last encounter between James and Angela takes place in a stairway with its walls engulfed by flames that, like those of the various hells described by religions throughout the world, burn but do not consume, leaving that which they touch intact in a cycle of endless torment. When we as James enter at the bottom of the enclosed stairway Angela is standing unmoving about ten steps above us while silently contemplating a large frame hung on the wall, an objet d'art the flames seem to purposefully avoid. Contained within the frame is the flayed skin of what what appears to have once been a man, its hands and feet gone, its face reduced to a vague smear, a bloody stump where its genitals once were. It's a tableau that pays direct homage to the hazy anatomical nightmares of the painter Francis Bacon, and though it isn't explicitly stated in the game, it constitutes the remains of Angela Orosco's father.

James ascends the stairs, his presence again going unnoticed by Angela until he's just a few steps away, and finally draws her attention. She cries “Mama!” in an outburst of joyous relief and, for the first time in the game, voluntarily approaches another human being. This time James is the one who retreats, withdrawing back down the stairs as Angela eagerly advances, saying “Mama I was looking for you! Now you're the only one left! Maybe then... Maybe then I can rest.” Though it's unclear at first, 'now you're the only one left' is in reference to her dead father as well as her brother who, though we can't initially see due to the angle we're viewing the scene from, is likewise framed on the wall opposite from where Angela's father is hung, his flayed and mangled remains stretched in the same pose of crucified agony.

The question of why, after having already encountered Silent Hill's monstrous embodiment of her father in the form of Abstract Daddy, Angela is again faced with a manifestation of her father in the form of the skinned, maimed thing in the stairwell, can be explained by referring to another dual manifestation Silent Hill 2 presents to us, that of Mary and Maria.

Though it's easy to forget, the town of Silent Hill is a place of dreams as well as nightmares, and the cruelest thing it does, far worse than simply terrifying and killing you, is giving you what you think you want.

James receives such a cursed blessing in the form of Maria, a woman who looks almost exactly like his deceased wife Mary, with several key differences. Where Mary was restrained, Maria is open. Where Mary was sexless, Maria is flirty. Most importantly, where Mary did everything she could at the end of her life to push James away, Maria openly, unabashedly needs him. Of course, Silent Hill only gives Maria to James in order to rip her away in as vicious a manner as possible, executing and resurrecting her again and again. After realizing he killed his wife James is able to conclude that Maria was born from the conflict inside him, the incompatible compulsions of concern and resentment, love and anger. The flayed manifestations of Angela's father and brother are the product of a similar inner conflict in her, but they're even more violent than what James experiences, the result of a mental turmoil that's even more intense and unresolvable.

Angela's flayed and castrated father and brother are the closest things to idealized versions of them her tormented mind is capable of manifesting. Without hands and feet they have nothing to strike her with. Without bodies they have nothing to move against her with. Without genitals they have nothing to violate her with. Even the faces burned into her mind are erased. Here, finally, are a father and brother incapable of hurting her, not so much objectified as aestheticized, reduced to abstract representations that she can safely behold up close like pieces in a gallery—though, like Maria's impact on James, these figures do nothing to soothe Angela's mental illness or the pain accompanying it.

Angela Orosco's psyche only deteriorates over the course of Silent Hill 2. There is no upswing, however fleeting. The lone trace of hope comes from us, the audience, as we watch her fall and ever more desperately yearn for someone to reach out and catch her, even as it becomes indisputably clear that that is simply not the story we are being told.

By the time of the fourth encounter in the burning staircase, Angela's mental state is so degraded that she initially mistakes James for the mother she came to the town of Silent Hill in search of. It seems like an error that's more a product of desperation than delusion and, as with so many of her other precarious mental states, it disappears as quickly as it appears. Angela makes physical contact with James only to realize her mistake and recoil, retreating back up the stairs as she delivers yet another apology. What follows is the most grudging expression of gratitude in video game history as Angela forces herself to say “Thank you for saving me.” then follows it with “But I wish you hadn't. Even mama said it: I deserved what happened.” revealing even the love of the mother she came to Silent Hill in search of is poisoned by abuse.

Angela's guilt and self-loathing is rooted just as much in her feeling responsible for the sexual abuse she was subjected to as it is motivated by anguish for stabbing her abusive father and brother to death. There seems to be no hint in her mind of the possibility that her violent acts could be justified as self-defense. She holds herself equally responsible for both the abuse and the killings, perceiving both as consequences of her own personal failings.

When James disagrees with her about the abuse being her fault, she brushes him off. The cutscene switches to a first-person perspective that looks up at Angela as she turns away and says “Don't pity me. I'm not worth it.” in a move demonstrating how mental illness is, by nature, immune to reason.

It's at this point that the game does something that's both incredible and unforgivable. Silent Hill 2 does to us, the player, exactly what it's been so mercilessly doing to its characters over the course of the narrative: It gives us what we think we want.

Angela Orosco turns back, looking us directly in the face as she says “Or maybe, you think you can save me. Will you love me? Take care of me? Heal all my pain?”

This is precisely what we, the player, have been hoping for. Angela's appeal for help is no less real for her cloaking it in a protective layer of acerbic sarcasm. She's finally doing what we've yearned for her to do all this time, the only thing we can ask of any severely mentally ill person: She's appealing to another human being for help. It is at this point that reality comes crashing down upon us.

We can't help her.

The switch to a first-person perspective is a vital element of what the game is trying to communicate. Angela is a few steps higher than us on the stairway, but she is not above us so much as apart from us, the perspective not implying superiority but distance, a profound remoteness that makes us feel like, even though she's only five steps away, she inhabits another plane entirely, one forever unreachable.

This is not James's perspective. When the first-person shot ends and the game cuts back to a two shot it's revealed that James has already looked away from Angela, allowing his head to fall so he's staring at the ground. If we were looking at Angela from James's perspective, the first-person shot would end with us looking at the stairs, not her.

Angela is not just making her appeal to James, she is making it directly to us, the player, asking us if we, who have invested so much hope in her recovery, have the capacity to dedicate a significant portion of our own lives to helping her maybe find a form of existing in this world that's slightly more bearable than the unrelenting nightmare she's currently trapped in. However, at this point in the game, both we and James have become the unwilling custodians of an awful truth.

We know that love is finite.

By now James's denial about the fate of his wife Mary has been washed away and he knows that, after three years of living with her as she endured a wasting and incurable physical illness, he killed her.

James has learned from firsthand experience that you can't heal someone by loving them, no matter how selflessly or unconditionally. That the thing that's consuming the person you love can just as readily consume you if you remain too close to it for too long.

Angela's appeal for help is met with the deafening silence she anticipated. Sarcasm becomes contempt as she mutters “Hmph. That's what I thought.” and returns her gaze to the mangled human remains hung on the wall, the closest thing to a real human relationship she's capable of experiencing.

James continues looking away, fixing his eyes on the stairs until Angela turns back to him, extends a hand, and says “James, give me back that knife.” signaling her renewed intent to end her life. James refuses, unable to be party to another death even if he knows Angela's intended suicide isn't the result of a wish to die so as much as a radical form of pain relief in which death is a tragic side effect.

After his refusal to return the knife Angela asks James if he's saving it for himself and, just as he did during their second encounter in the apartment building, James lies, saying “Me? No, I'd never kill myself.” demonstrating how, even after learning the truth of what he did to his wife, he still can't bring himself to acknowledge his own self-destructive tendencies.

In no shape to argue, Angela turns and walks away, ascending the stairs with the grim resignation of a woman marching to the gallows. Flames rise to fill the space between her and James, rendering her physically as well as emotionally unreachable.

“It's hot as hell in here.” James deadpans, establishing that the fire hurts just like anything else despite its supernatural nature, the hope of saying anything helpful or constructive now gone as we're reduced to stating the obvious, even as we watch Angela drift off into darkness.

She pauses, turning back to us one last time.

“You see it too?” She asks, which taken on its own seems like an odd question since Angela knows James has already witnessed—indeed, killed—the Abstract Daddy monster, one of the most unbelievable things Silent Hill's ever produced. Instead it seems as if Angela is not directly referring to the fire so much as what it represents, the force that's conjuring it.

Angela Orosco is a person who is very accustomed to other people not seeing the pain she's in. Perhaps that's the reason she's looking for her mother in the first place. Maybe she didn't come Silent Hill in search of love, which she knew she wouldn't get from a woman who blamed her for her own abuse, but because her mother would at least know what she'd been through and be able to see the pain she's in, even if she'd do nothing to relieve it. Sometimes we're so desperate to be with someone who knows and understands what we've been through we'll do anything to be with them, even if they played a part in what was done to us, even if it's still true that all they do is hurt us.

Despite all the supernatural insanity both she and James have witnessed up to now, Angela finds it remarkable that another person is able to sense the hell she exists in. Still, if anything, the distance between her and James is even greater than before, salvation even more impossible. Angela's last words before leaving us for the final time are definitive.

“For me, it's always like this.”

It's a line that requires no commentary from the likes of me.

There are many theories scattered amidst the flotsam and jetsam of Silent Hill fandom concerning the ultimate fate of Angela Orosco. The general consensus appears to be that she died, but that doesn't concern me. My fear is that Angela is alive in hell, a hell that isn't the organized chaos of Bosch or the frozen wasteland of Dante or the social paradox of Sartre—rather I'm afraid that the author Walt Williams was correct when he wrote “Hell is a small room and enough time to think about how much you hate yourself.”

My nightmare ending for Angela has her returning to the empty room in the apartment building where she met James for the second time and gave him her knife. In my nightmare she is again lying on the floor, the only difference is now her back is to the mirror, her glazed eyes permanently fixed on a bare spot on a featureless wall, her mind entombed in the absolute certainty that there is no need for her to ever look anywhere else, that there will never be anything in the mirror worth seeing.

The cutscene concludes and control of James Sunderland is returned to us. We can attempt to follow the receding figure of Angela, but all that means is being repelled by a wall of flame. There is nothing to do but turn around, nothing to do but finish our own story and leave Angelo Orosco forever behind, even as the questions raised by her fate endure within us.

Silent Hill 2 asks us to examine how, as the imperfect creatures we are, we are fundamentally limited in our capacity to love and care for another human being, now matter how much we want to.

When people say that Silent Hill is better than Resident Evil, this is the kind of thing they're talking about.

Then again, Resident Evil 2 does let you play as a giant lump of tofu.

Let's just say both franchises have their strengths.

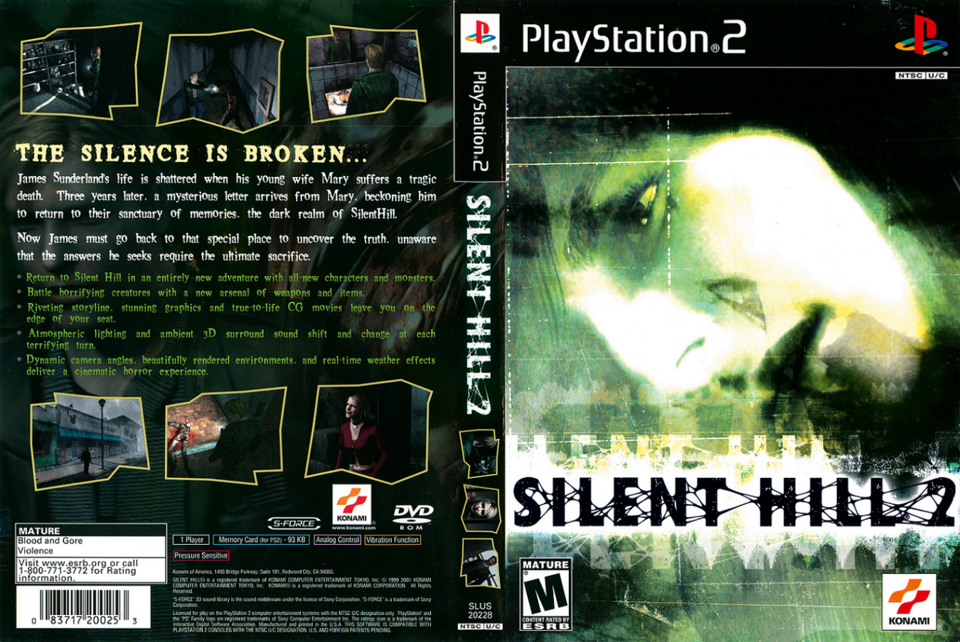

COVER GIRL

The possible ways the conclusion of Angela's story could have been mishandled are legion, yet not only do the game's designers manage to not fuck it up, it's such a resonant scene it can make the end of Silent Hill 2's main narrative feel a little underwhelming, even as we're forced to battle two Red Pyramid Things at once and re-kill our freshly not dead wife.

The impact of Angela's four brief scenes will naturally vary for each person who plays the game. There's plenty of mind-shattering human misery to go around in Silent Hill 2, and which story resonates the most depends on where each individual player chooses to focus their attention.

Part of the thing that makes Angela's story so special is it simultaneously being so incredibly affecting and, in the context of the larger game, so incredibly easy to overlook. Angela is a character who rewards our attention, her story shining through as something truly special even as it attacks our heart with the savage gusto of a boxer pounding away at a speed bag. The people involved in the creation of Silent Hill 2 seemed to understand that they'd managed to fashion something incredible with Angela, given how they saw fit to overlook the main characters and instead put her face on the box, despite her having no significant impact on the game's main narrative.

In a fate that oddly mirrors that of Angela Orosco's story within the game, the image on the cover of Silent Hill 2 is easy to overlook if you aren't paying attention—and why would you? As with so much else in the town of Silent Hill, itself a liminal space enshrouded by fog and darkness and madness, the portrait of Angela is obscured. It's a closeup taken from the CGI cutscene of her that's shown during the second encounter when we find her lying on the floor inside the hotel, but half of her face is cut off and, with the notable exception of her left eye, every other part of her is partially or completely hidden. The image is too bright in some places and too dark in others, both overexposed and underexposed so that much of her face is not shown but rather implied in a haze of abstract shapes. If you only glance at the cover your mind tends to automatically fill in the gaps so you get the impression of a complete portrait. It's only when you apply your full attention that you begin to realize just how little is really there, that her nose and cheek are indistinct blobs reminiscent of phosphene afterimages, how her mouth and chin are gauzy shadows. Even her eye, the only clearly depicted feature, is utterly empty, glazed and hollow as it stares fixedly at nothing.

By the time Silent Hill 2 was released the Atari golden age of compelling, beautiful cover illustrations was well and truly consigned to the dustbin of gaming history, with box art serving little purpose beyond identifying the game within. The whole Silent Hill franchise has a long and storied history of putting obscured human faces on their games, but the Silent Hill 2 box art stands out for its artistry and its subject. Not only does the featured character have no direct impact on the game's main story, but the specific image the artist chose to feature is that of Angela stranded in the darkest recesses of despair. Once we play the game, we know.

The box art of Silent Hill 2 is the image of someone contemplating suicide.

As far as I can tell it's not intended to shock, or be some kind of morbid joke. It seems the artist simply found something powerful in this specific image of Angela Orosco, something real that was worthy of attention and elaboration. It's a study in ambiguity that illustrates one of the fundamental contradictions of human relationships, how the closer we get to someone, the more aware we become of how there are parts of them we'll never truly know; sometimes because they're unaware of it themselves, and sometimes because there are things that simply can't be fully articulated due to the inherent limits of communication. It's places like this where art attempts to fill in the gaps, allowing us to hint at things that would otherwise remain forever obscure.

The more intense a feeling, image, or idea is, the more desperate we become to find some way to express it. It's tempting to think this might be one of the reasons why artists so often harbor some form of mental illness, however it's also often true that the people who create some of the most disturbing, nightmarish imagery known to man turn out to have kind, gentle personalities, while artists who maintain a transgressive, Byronic persona were usually assholes to begin with who use their art as a convenient way to justify their assholery after the fact.

Art without sympathy for the human condition can still be fantastic, but will by nature fall short of the sort sublime transcendence we instinctively seek. As the endlessly quotable Albert Camus said: “A man's work is nothing but this slow trek to rediscover, through the detours of art, those two or three great and simple images in whose presence his heart first opened.”

Then again, he also said “It was better to burn than to disappear.”

As Angela Orosco's fate demonstrates, there is only so much burning any one person can endure before the prospect of disappearing becomes, not attractive, but an act of final, desperate recourse.

Silent Hill 2's story takes pains to avoid either endorsing or denouncing euthanasia and suicide. Instead it chooses to focus on the circumstances that drive people to such extremes of behavior and how, in the aftermath, survivors do or do not manage to endure. The genre of horror is uniquely suited to explore the more... let's call them 'unpalatable aspects' of human existence, the parts of ourselves and our environment we desperately seek to escape even as we continue to harbor a perverse interest in them we can never fully banish: Mortality. Madness. Cosmic indifference. Hearing about someone who got their toenail ripped off by a screen door. These things are relatively easy to tap into on their own, the real trick is injecting some humanity into them, finding some trace of compassion amidst the chaos of a world that stubbornly resists our efforts to force it to make sense or, at least, take our feelings into account.

ALL THOSE WE CAN'T SAVE

Every horror story is about someone encountering something they are unequipped to deal with. This is why 1979's Alien is a horror movie while its 1986 sequel Aliens is more of an action movie. In Alien the characters have no notion of the danger they're in until it starts bursting out of their chest and cramming tightly rolled magazines down their throat. By contrast, in Aliens, the characters at least know enough to send in a group of heavily armed space marines and a less homicidal android to resolve the problem of an alien infestation, even if they ultimately prove to have grossly underestimated the strength of their enemy, as well as the pure evil that is Paul Reiser.

This phenomenon isn't limited to the Alien franchise. If the titular Rosemary of Rosemary's Baby knew she was giving birth to the Antichrist from the very beginning the movie wouldn't be horror but a comedy about wacky neighbors. The Shape of Water is romance instead of horror because its heroine has the mental fortitude to look beyond her piscine paramour's uncanny appearance to see all the things about him that are worth loving.

All the horror movies cited above are about reality turning hostile, but there is another way to move the needle into the realm of horror, and that is madness. Many—indeed, even most—horror stories like to mix the two, having characters question their sanity as the reality they inhabit warps around them in unnatural ways. Unfortunately this trick is often used as nothing more than a way to fill time between scares, and if you cut out all the scenes of people prevaricating over whether or not someone is insane or facing a real objective threat, most horror movies would be half an hour long, not to mention vastly improved. Movies where insanity itself is the sole source of horror are relatively few in comparison, but there are examples: 2001's Session 9, 1965's Repulsion, and 2006's Bug, to name a few.

It can take remarkably little to convert one into the other. With a few changes to the script 1973's The Exorcist could become the story of a girl who is suffering a severe mental illness instead of being possessed by the devil, a shift that would probably make it less entertaining but more disturbing. The opposite is also true. Crave, the 1998 play about love and mental agony by Sarah Kane, contains the line “I try to pull it out but it gets longer and longer, there's no end to it. I swallow it and pretend it isn't there.” an expression of psychic anguish that could just as easily be a flash horror story.

Exactly which mental illness frightens us most changes with the times. Senile dementia has become a popular topic for horror as people live longer and it touches more and more lives. Meanwhile, as things like anxiety and schizophrenia and post-traumatic stress disorder become less stigmatized, they drift out of the realm of horror and into more dramatic, award-bait fare. Still, one of most common mental illnesses is conspicuously absent from the realm of popular entertainment, not due to stigma or disinterest, but because it's so damn difficult to make it interesting. I speak, of course, of everyone's favorite: depression.

Depression is naturally resistant to artistic interpretation since all art is, on some level, entertainment, and must make the audience feel something in order to attract attention. This is the antithesis of depression, where all feeling goes to die. Constructing meaningful art out of depression is like trying to get high on anesthesia. How do you take something that's so defined by its crushing, unrelenting sameness and render it captivating?

It's certainly not impossible. William Styron's memoir Darkness Visible, the aforementioned plays of Sarah Kane, and the poems of Philip Larkin are some examples of depression being successfully incorporated into art. Such art is never going to capture the wider public's imagination, but that isn't necessarily a bad thing. If a play containing lines such as “Only love can save me and love has destroyed me.” and “I'm evil, I'm damaged, and no one can save me.” and, of course, “I am so tired.” became as popular as the Harry Potter series, I would be more concerned than delighted.

This is partially why Angela Orosco is so exceptional, why she's made such an indelible impact on me. When I watch her the intrinsic weaknesses of Silent Hill 2, the cheesy acting, the dated graphics, the odd casting choices, the awkward plotting, all of it is rendered irrelevant by a character whose mental anguish, particularly her depression, is so meaningfully rendered.

I'm naturally biased, of course. We all desire to see our own experiences represented in the art we consume, even as we attempt to use it to bridge the gaps between ourselves and other people. Enhancing this feeling and forging mutual interest into a community is the sort of remarkable thing a dedicated fandom can accomplish when it isn't exclusionary.

Or pedantic.

Or hateful.

Or completely toxic.

I'm sure we'll get there one day.

Anyway, there's a deep comfort in seeing something that's had a profound effect on you resonating just as deeply with other people.

The fourth and final encounter between Angela and James is powerful because it's so illustrative of the divisions that haunt us. There are times in my life when I've been Angela and times when I've been James, when I've been the one who leaves and the one who is left. However the scene isn't just about how relationships implode and we're forced to leave one another behind, but how we so often end up divided against ourselves, how there are parts of us we're forced to conclude we'll never be able to fully repair and must instead adapt to, attempting to grow around our damage like a tree gradually enveloping a scar over the course of years and decades.

I'm not only interested in Angela Orosco because I sympathize with her emotional plight. I have an unwholesome obsession with deeply flawed tragic female characters that I should probably tell my therapist about, and there's something about studying the trajectory of how people find their way to ruin that I find compelling.

Everyone's road to Hell is different, every brick composing it a unique instance in the annals of dysfunction. It often takes a lifetime to look up and see the truth.

The road to Hell is a circle.

One that can expand forever without leading anywhere.

Such is the language I resort to when struggling to define mental suffering. There's no vast lexicon to detail the pain of depression. Physical pain comes with a glossarial universe: shooting, itching, sharp, dull, aching, and stabbing, to name but a few. Despair is just despair. If you want to get technical you can use the psychological term negative valence, but that's it. The mentally afflicted are forced into the role of poet if they hope to effectively convey some measure of the true scope of their agony, something they're often too busy suffering to do. As all of us, the mentally ill and mentally robust alike, grope for some way to define what's going on inside us to one another, there is one word I'd like to circle back around to, one I've found to be remarkably versatile: Burning.

Fire can be a metaphor (or simile, if that's your kink) for pretty much anything: destruction, passion, change, pain, rapture, fear, renewal, chaos, and so on. As my rambling paean to the character of Angela Orosco and what she means to me nears its conclusion I would like to heap one additional meaning onto the pile, one I came up with on the fly during therapy while grasping for descriptors: Depression is like fire in that it takes a million different things and converts them all into the same heap of ashes.

It's a fate Silent Hill 2's Angela Orosco allows us to escape, however briefly, by giving shape to those parts of ourselves that are so often hidden, scavenging meaning from emotional ruin. It's no coincidence that two of the most poignantly beautiful pieces of music in the entire Silent Hill series are deployed in James's second and fourth encounters with Angela. The first piece is a light yet resonant piano score, a simple repetitive theme circling back back upon itself while being accented with sparse glockenspiel notes whose rhythm is subtly buoyed by an airy synthesizer, the sparse instrumentation combining to foster an impression of elegance and mystery that should be completely out of place in a scene where someone is contemplating hurting themselves in a dingy hotel room, yet somehow it works. The second piece is another short repeating piano theme but this time the accompaniment soars above it, an aching yet sinuous violin score alternating with gently chiming glockenspiel, all underlain by the ambient diegetic murmur of crackling flames to foster an undercurrent of churning primal uncertainty.

The music goes a long way toward elevating these scenes, keeping them from becoming crass or exploitative by attaching something beautiful to something unbearable. Such unions of the personal and universal are something we naturally recognize as embodying the contradictions that make us human, something we instinctively seek out since seeing how the same thing affects other people differently can help us learn something about ourselves, and give us occasion to indulge the hope that we may yet somehow manage to cling to some slim fragment of everything we've lost, without it dragging us into oblivion.

- Fanart Links

Angela Orosco Stairway of Fire art print

For Me, it's Always Been Like This