I've been batting around a game design observation that I don't have a name for yet ("something something confluence", but to paraphrase BioShock Infinite the mind struggles to create puns where none can exist) but pertains largely to crafting, survival and "life-sim" games. Chiefly, that these games present a concrete, primary objective and then gives the floor to any number of optional modes and practices that the player might partake in. Of course, some if not most of these games lack any kind of central encompassing prerogative, expecting players to "make their own fun" instead, but I'm less concerned with those for the time being.

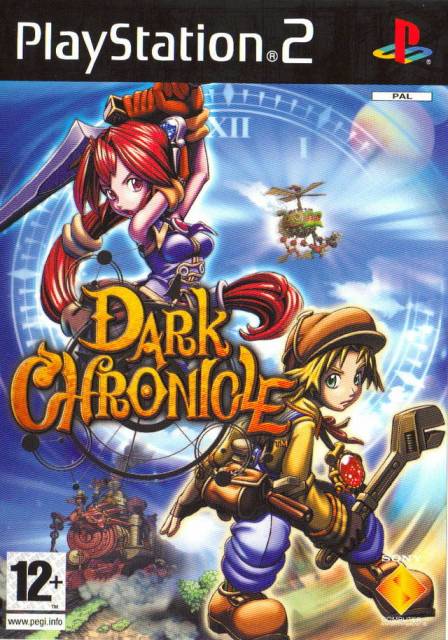

With those games that do have that focus, there's a central pillar that everything flows into, like a conflux of rivers and streams. This might be to defeat a big villain or hit a certain milestone with your crafting, and if the game is designed right every other distraction the game presents will allow you to move closer to completing this objective by one means or another. Dark Cloud 2 is a game I'm often fond of invoking in cases like these: the goal of Dark Cloud 2 is to complete all the dungeons and prevent the world's destruction. Building up towns via the Georama system is beneficial to this purpose because it unlocks new items to use, fishing provides money and healing items, photography provides new inventions which can lead to better equipment and consumables, and even the golf-like mini-game Spheda provides all sorts of useful rewards. Ditto with Persona, where everything you do in the real world - developing social links, buying and upgrading items, completing side-quests - directly feeds into the game's dungeon-crawling core. This idea isn't unique to crafting and life-sims of course - you could apply it to almost any type of open-world game or RPG with a large enough mini-game/side-activity quotient - but it's more pronounced in those games that purport a greater variety of freedom to do whatever you want, while also ensuring that you're ever so gradually moving towards an end-game state in case you ever felt like bowing out of the game and wanted some closure to help send you on your way.

The next step for something like this would be a game design nexus: instead of benefitting a single central objective, every gameplay mode benefits a different one, enticing you to explore the full spectrum of what the game has to offer. This prospect is contingent on the player actually wanting to do everything on offer - little point giving them rewards to be applied to a mode they don't ever want to touch, like a new fishing rod for completing a sidequest when they'd prefer to never cast a single line - but it's the sort of reward-rich gaming experience that corrals players from one attraction to another, like a tour guide at a theme park.

Not every game can do all this well, and it seems exceptionally hard to do so, so I'm always impressed at the games that actually do pull it off. It's why Terraria is my favorite Indie game and Dark Cloud 2 is my favorite console RPG: they're not just great games with plenty of varied content, but they pull off the challenging juggling act of maintaining interest in several different gameplay modes at once, offering so much to do while also ensuring that there's a central through line to stop their players from becoming too distracted or intimidated by choice. I've heard that a lot of MMOs are built on similar techniques, and it's why I can understand when Rorie or someone else tells me they've spent a good portion of their lifetimes playing WoW.

Talking of player choice, you have the choice to review the following two blogs. I'm kidding; if you've read this far you're actually legally obliged to do so. Sorry, I don't write the rules:

- The final Indie Game of the Week for July 2018 was Puzzle Puppers, a breezy puzzle game in which you direct one or more stretchy doggos around a maze of food bowls, optional meat collectibles, and stage hazards. The game suffers a little from having a very gentle difficulty slope and little in the way of variance - as far as I recall, it doesn't change the background or music once throughout its eighty stages - but it was definitely on the right side of solvable up until its memory-intensive final stage. Eminently disposable if I'm being brutally honest, but I always appreciate a puzzle game I can actually complete. (Conversely, its closest equivalent Snakebird was a game that stumped me after only an hour or so.)

- We turn the spinning table once again to reveal the antidote to the poison you just drank, if by poison I mean "lack of anything to read" and antidote as "some interesting history to read about the Sega Mega Drive". Look, I'm still working on my analogies and metaphors, OK? The tortoise and the hare didn't build Rome in a day. Mega Archive: Part V covers a formative period of the Mega Drive's lifespan: November 1990 saw both the introduction of Sega MegaNet, a nascent subscription-based digital distribution service, as well as the arrival of the Mega Drive's greatest nemesis and rival - the Super Nintendo Entertainment System (or, to be more precise, its Japanese equivalent the Super Famicom). We're also seeing the increased presence of EA, which for all its faults helped the console find greater purchase in the American and European marketplace with their realistic sports simulations. All that and more frickin' shoot 'em ups await your perusal in this fortnight's Mega Archive.

Addenda

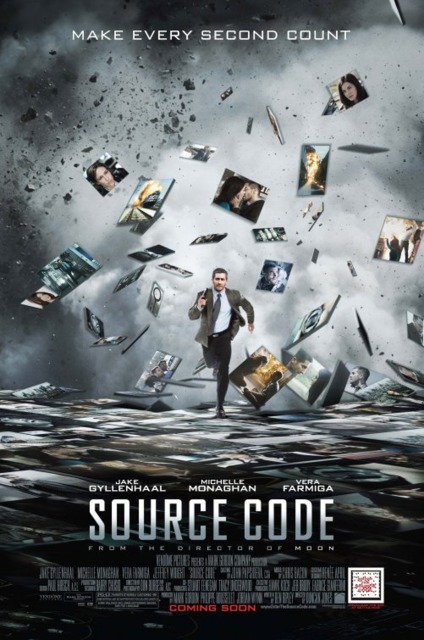

Movie: Source Code (2011)

A man wakes up on a Chicago commuter train midway through a conversation with the woman sitting opposite him. He's disoriented - from his perspective, he's an army helicopter pilot currently stationed in Afghanistan - and searches the train for answers only for it to explode after eight minutes killing everyone on board. It's a great way to start a sci-fi movie, dropping the audience into the action at the same moment as the protagonist in a similarly bemused state, and it almost reminds me of the cold opens Star Trek: The Next Generation would have where everything's different and you'll need to stick around until after the intro credits to find out why.

Captain Colter Stevens, played by Jake Gyllenhaal, is actually part of the secret military Source Code project: a means of reliving the final eight minutes of a person's life through some manner of quantum entanglement. Rather than going back in time and reliving the experience, the volunteer is taken to an alternate reality to live out the same period of time as a different person. Stevens's goal is to determine who planted the bomb on the train that caused it to explode, as there's evidence to suggest that an even larger dirty bomb is set to explode in the heart of Chicago. Stevens is told not to worry about the particulars and to focus on the mission by the project leader Dr. Rutlege (Jeffrey Wright) and the sympathetic Air Force Captain Goodwin (Vera Farmiga), jumping back again and again Groundhog Day style to further his investigation.

I was impressed most of all by just how compact and clever the movie is in its construction. It doesn't necessarily feel the need to dawdle or screw around with the Groundhog Day concept - for one thing, time is still passing normally outside the Source Code machine, so there's a literal ticking time bomb to keep things moving - yet manages to find time for the occasional moments of humanity. It's definitely a touchy-feely sort of movie at points, like when Colter is adamant that he get in contact with his estranged father once he realizes his situation, or how his paranoia about his fellow train commuters causes him to make a few "politically-motivated" (as in, vaguely racist) mistakes. I also appreciate the way it establishes the rules of hopping into these alternative timelines and the repercussions it has for those particular realities. It's not so much a movie with an ending but one with a lot of endings, and not in the LOTR: Return of the King sense: each reality has a different outcome due to Stevens's actions (though most still involve the train exploding) and given that the Source Code protocol also exists in many of those realities, the potential for stopping terrorist acts or other large-scale tragedies is potent indeed.

Source Code is the second feature from Duncan Jones, and displays many of the qualities as a filmmaker I've come to expect from the erstwhile Mr. Zowie Bowie. I've been meaning to watch Source Code ever since I watched his previous movie Moon - which was also hard sci-fi dealing with an outlandish sci-fi concept in a naturalistic way, asking questions about the nature and inherent value of humanity along the way - but I guess it wasn't until this year's push to watch more movies that I finally got around to it. I'd happily recommend Source Code to anyone who enjoyed Moon (and vice versa, of course) - it's sharp, concise, contemporary sci-fi with a great premise that doesn't lose sight of its human players in the process, while still staying clear of overly mawkish sentimentality. I'm less interested in Warcraft and Mute, Jones's less-regarded subsequent movies, but I am hoping he bounces back for his upcoming Rogue Trooper: an adaptation of the 2000AD comic book, a staple of my childhood.

Game: Starbound (2016)

I bought Starbound to cheer myself up after an unfortunate situation earlier in the week, and have been glued to it ever since. Starbound wears its Terraria influence on its sleeves, particularly with the game's aesthetic, but attempts to one-up the terrestrial simulator by going extraterrestrial.

Rather than building the game's difficulty curve and progression through a gradual descent to the planet's molten core, Starbound is set across multiple planets with increasingly more challenging foes and more valuable minerals with which to craft better equipment and resources for the battles ahead. It's far more focused on combat as a result, and even has these set-piece missions in pre-generated dungeons that cannot be edited or demolished - rather, it's a traditional 2D dungeon crawl with keys and lock puzzles in the vein of something like Zelda II: The Adventure of Link. The difficulty curve is that much more pronounced also, and you really have to take your time mining newly available resources whenever they appear for the extra edge they can provide.

I don't necessarily agree with everything Starbound introduces. For one, it decided to include a food/hunger survival system that was lacking in Terraria with good reason. It's a hassle to keep the protagonist's hunger gauge in check and to maintain a farm back at your homebase, which is why the game offers a "casual" difficulty move that excises this feature as well as negating any death penalties. It's also a little more corraled than Terraria was for better or worse, dropping you into an intergalactic mystery concerning "The Ruin" - a multi-tentacled space monstrosity that has already devoured the Earth and threatens to do the same for all other sapient-occupied planets - and a collection of MacGuffins scattered across space which are, of course, the only means of stopping its assault. As you explore planets to gather hints to the locations of these artifacts, you can also decide to spend your time elsewhere, either mining lifeless moons for valuable ore deposits or building up a settlement on whichever rock you've decided to inhabit for the long-term: it's not entirely unlike No Man's Sky in that regard, where you can warp back to your "home planet" no matter where you and your ship happen to be in the galaxy and work on building rooms and extensions and crafting stations and inviting NPCs to join you.

To tie this back into the introduction to this week's Sunday Summaries about game design confluences, Starbound excels partly because all of its modes and features are complimentary: if you decide to wander off and catch fish or bugs for a while, they'll still have some beneficial effect on your main objective. Developing and upgrading your crafting stations, or your traversal "tech" (Starbound cutely allows you to acquire a double-jump and a morph ball technique, the utility of which can be tweaked further), creating desirable settlements for handy NPCs, or completing side-quests all provide boons you can take with you wherever you boldly go.

Starbound is pretty much all I wanted from a sci-fi Terraria variant, with a staggering amount of content to look forward to and a core progression that may take me several dozen more hours to complete. More so, it scratches the itch of wanting to play more No Man's Sky with all the current dialogue around its NEXT update - while I enjoyed my time with the game and didn't quite reach its end state, I have the platinum trophy and was happy to leave it behind. My only issue is that Starbound kinda runs like garbage on this laptop, and I've been busy troubleshooting ways to lessen the FPS drain, from modding out the game's dynamic lighting to reducing the cache strain. Still, it's been worth the hassle so far.

Log in to comment