This is a party to which I’m about seven years late, I know. But this weekend, I finally watched School Days, an anime series from 2007 that was based on an adult visual novel of the same name from two years earlier. Some of you may have already seen it. Others of you may only be familiar with the show through a meme that spawned from footage aired in the original time slot of its delayed final episode.

The content of the show’s ending is what in part led to the delay of its airing, and to the meme. But another event unrelated to the show itself, specifically a real life murder that was prominently in Japanese headlines at the time, was what resulted in the delayed broadcast. Ancient internet memes aren’t what I’m here to talk about, though.

Having watched the full twelve episodes myself, there’s actually a lot more to the show than just an internet joke or an ending shocker, and it’s actually had me thinking quite a bit. Not just about the show itself or the visual novel that spawned it, but about games in general, and what they could learn from it. School Days is a show that’s known mostly for how it ends, but the path it takes to get there is just as important as the final few minutes.

(Major spoilers for School Days follow.)

Introduction

The basic premise of the game, and the anime, follows Makoto Itou, a high school student that develops feelings for fellow student Kotonoha Katsura. His classmate Sekai Saionji helps introduce the two and encourages their relationship, despite the fact that she has hidden feelings for Makoto herself.

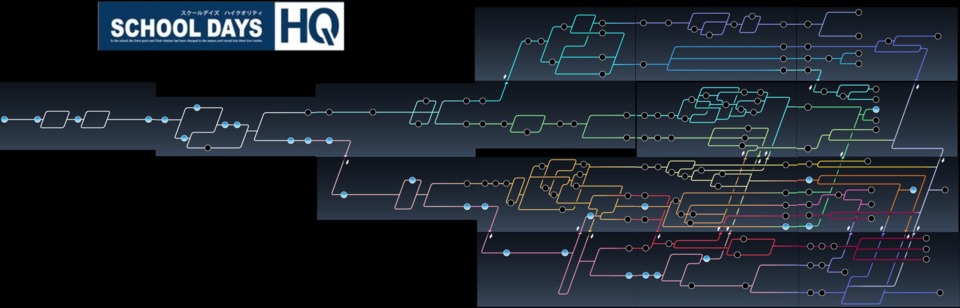

From this set-up, the game has over twenty endings; most of them are good, some of them are bad. But what makes the game somewhat notorious is that the bad endings take things to the extreme, with one or more of the characters meeting their end in death. And the producers of the anime took this fact to heart.

The Plot

On the surface, School Days feels similar to other anime series that are romantic comedy-dramas set in high school. The opening credit animation hints at the love triangle that serves as the core, but is otherwise seemingly innocuous. The series is also not above going to some of the most worn clichés of its genre, with an entire episode set at a water park and all of the girls in swimsuits, the school festival serving as the setting of major events later in the story, and numerous gratuitous shots of breasts and panties. And yet, in retrospect, it feels as though these tropes are only present to instill familiarity and to keep the viewer watching as the real story plays out.

The series begins with an indecisive, inexperienced Makoto pining for the demure and quiet Kotonoha, going so far as to be on a first-name basis with her as they finally start to date and forge a relationship. But Makoto is entirely dependent on his classmate Sekai, who constantly feeds him advice on how to advance the relationship and not screw things up. She even encourages him to practice his advances with her, though she has her own interests in mind as much as if not more than Kotonoha’s.

But just as Makoto makes real headway in his relationship with Kotonoha, having been invited to her home and entering a comfortable first-name basis with her, he grows tired of her. He prefers to spend more time with Sekai, abandoning the pretense of “practice” for a more truly physical relationship. And though he feels like Sekai is more and more the girl he prefers, he refuses to officially break things off with Kotonoha.

What follows in the plot plays out as if someone played a visual novel and constantly made poor decisions. Though Makoto starts off as sympathetic and somewhat likeable despite his indecision and mistakes, he becomes worse and worse as a person as time goes on. Makoto eventually starts falling for other girls. Just as he leaves Kotonoha hanging as he cheats on her with Sekai, he cheats on Sekai with another girl, and then others. It becomes clear that he has no interest in the needs of those he’s with, more concerned with momentary pleasure than forging relationships.

This sense of betrayal is best exemplified by Kotonoha’s plight. She’s bullied by her classmates, whom all assume that Makoto had broken up with her (despite his never telling her), and as Makoto spends more and more time away from her, she grows more despondent. The strain on her emotions, and her concern over whether she did something wrong, eventually causes her to crack. Sekai, too, is devastated by the betrayals, taking a long absence from school after she falls into a severe depression. And when she starts feeling ill, and possibly gaining weight, she fears that she’s pregnant.

Eventually, everything comes crashing down, as Sekai tells Makoto the news and chastises him to take responsibility. Word spreads through the whole school, and soon no one is willing to speak with him or return his calls. But true to form, Makoto refuses to take responsibility for his actions. Instead, he’s frustrated with Sekai for ruining his life. He by chance stumbles across Kotonoha, who despite his treating so poorly is blissfully ready to accept him as though nothing happened.

But Makoto makes one bad decision too many. He continues to treat Sekai poorly, and she snaps, stabbing him to death in his apartment, only for Kotonoha to arrive later and find his body. Kotonoha in turn arranges a meeting with Sekai using Makoto’s phone, and with one last twist of the literal knife, kills Sekai and cuts her open to see if she were truly pregnant. (She was not.)

Analysis

Overall, the plot of the show is like one long tear-down of the very genre it’s adapting. Makoto goes from immature, inexperienced, and indecisive to being a callous, promiscuous idiot. His attitude destroys his relationships one at a time until only the highly unstable love triangle is left. And then, well, I already explained how it ends. Badly.

And it’s not as though the ending comes from out of nowhere. There are hints, some subtle, some not so much. The first and last episodes begin with their title cards shattering like glass. Kotonoha’s descent into obsession and madness is highlighted with moments such as a prolonged shot of a knife beside her in the kitchen, or her “correcting a mistake” in her knitting by calmly unraveling the entire project. Sekai and others refer to Makoto early on as an idiot. At one point, in a rare moment of meta-commentary. Makoto himself derides the protagonist of a video game in what could have otherwise been a throwaway line of dialogue. From the very start, the show is geared toward taking its characters, and its audience, to the worst possible conclusion, but hides its intent behind standard elements of the genre and humorous moments that play counter to the nature of how the story ends.

Though the show may be remembered in the long run for its ending and for a “nice boat,” it’s also inspired. It goes in directions that most video game adaptations would never go. That the production staff made the conscious decision to adapt a bad ending path and to take it as far as they did, is in some ways worthy of applause on its own. The show isn’t perfect, by any means, but it stands out by taking one of the most formulaic of anime formulas and turning it on its head.

What Games Could Learn

School Days is hardly the only visual novel out there to feature bad endings that are as bad as they are. But the fact that such endings are possible, and even the fact that its anime adaptation went that route itself, is something that I feel more games and even their adaptations could learn from. Video games that offer the player choice, particularly moral choice, rarely deliver true punishment for making poor decisions.

Yes, some games do penalize the player for making certain choices. In Dragon Age: Origins, Alistair will straight-up leave the party if you take it easy on his arch-enemy Loghain and conscript him into the Grey Wardens. In Persona 4, the game ends in a premature bad ending if you fail to give the proper responses to calm your other party members down. But in the former, you’re essentially exchanging one character for another of the same basic class, and in the latter, it’s easy enough to try again from the last save point. The penalties they present are minor and easy to recover from.

So what if Persona 4 were structured somewhat differently? What if the relationships formed had a more meaningful impact in the party and in the world? Intentionally or not, Yu Narukami comes off as a playboy capable of romancing multiple girls at once, and what little penalty there is easy to recover from. What if the player could only be locked into one specifically romantic relationship, and being caught cheating resulted in more dramatic, drastic effects? I’m not saying that Yukiko should fly into a murderous rage at seeing Yu cheat on her with her best friend…

…but what if the penalties were more severe, both in terms of the gameplay and in terms of the story? What if cheating on Yukiko led her to become distrustful of Yu and abandon the Investigation Team? You lose her Social Link and the Personae associated with it, as well as her abilities as a party member. And what if losing her in turn made it more difficult to rank up in the Social Links with Chie and other characters?

Or as another example, what about the Mass Effect series? Imagine for a moment the possibility that every bad decision and self-serving action that Commander Shepard makes over the course of the first two and two-thirds of the trilogy come back to bite him in the final third of Mass Effect 3. What if the ultimate ending weren’t based on the Crucible choice and certain relationship options, but on how Shepard’s actions had shaped the galaxy to that point, for good or for ill? What if being a colossal space asshole actually had ramifications that stripped you of the possibility of even having the chance at saving the galaxy? Three games of selfish actions and poor choices, all building to a finale that doesn’t reward you, but instead informs you of how unworthy you are as both a potential galactic savior and as a human being.

I understand the realities of game development. The more complex the design, the more difficult and time-consuming it is to implement. But if games wish to present moral choice and relationships with a sense of actual complexity, then the poor decisions the player makes should be properly accounted for, up to and including the negation of a possible "good" ending. What if Yu was a two-timing jerk and his actions were seen as a horrible betrayal? What if Shepard went too far and alienated everyone he depended on to fight the Reapers? What if Yu and Shepard’s worst enemies were the player’s inability to make choices that take the needs and feelings of others into account?

What if recovery isn't as easy as simply reloading from the last save point and trying again?

In Conclusion

It’s in this sense that visual novels, with their simpler designs, seem apparently able to take more risks with their choices and narratives than a standard big budget title. School Days is a simple premise that grow wildly out of the protagonist’s control to his own detriment, and it’s in that direction that both the game and anime are more recognized for. If other games from different genres that offered player choice had the means to send the player into an unrecoverable downward spiral of their own creation, then that would actually be an improvement, as paradoxical as that sounds.

Though it’s only an adaptation of a game, the School Days TV series is a clinic on how making poor player choices in games can be taken to their extreme. Throughout the series, every decision Makoto makes is terrible. He hurts those that love him without thinking about it, takes advantage of others for his own physical pleasure, and though it could be argued that he didn’t deserve to die, he pays for every last poor decision he makes with his life. And the only one that cares for him in the end is hugging his severed head while sailing on a nice boat.

Log in to comment