Note: The following article contains major spoilers for Halo: Combat Evolved. A special thanks to lunaramethyst, who helped me source information on its naming.

In 1999, a group of game developers and branding agents gathered around a whiteboard in a Chicago office. On that board were potential names for Bungie Studios's sci-fi war game set to release on the Apple Mac.[1] Those names included some cosmically bizarre choices like Hostile Environment, K3, The Crystal Palace, and most perplexing, Santa Machine.[2] But against the noise, one name stood out: "Covenant". Bungie's creation would be defined by its primary antagonist: an alien religion waging genocide against humanity.[1] Or it would have been if Bungie had followed the advice of the branding firm.

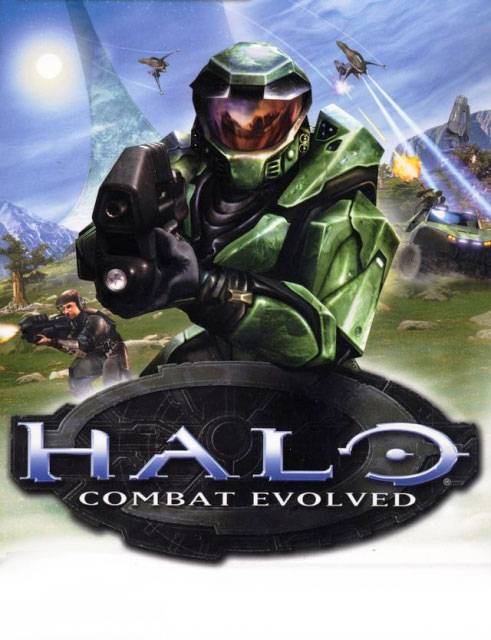

Artist Paul Russel had another name in mind, one that was not popular among the team: "Halo". Despite the lack of internal enthusiasm, "Halo" stuck. Microsoft, Bungie's eventual publisher for the game, bristled at the title. Shooters didn't have names as cryptic, religious, and god forbid, feminine, as "Halo"; they had violent, pithy monikers like Doom, Quake, and Counter-Strike. But in an act of independence and vision typical of the studio, Bungie refused to budge on the name. Eventually, Microsoft came up with a compromise: a subtitle. The game would be called "Halo: Combat Evolved", a nod to its ambitions of radically reshaping the action genre. Despite some consternation, Bungie agreed, and Halo: Combat Evolved released for the Xbox on November 15th, 2001.[1]

The battle for Halo's name reflects both the originality Bungie enshrined in the series and all the times that Halo's development almost took another path. Before Combat Evolved, Bungie was a team of roughly twelve to fifteen developers and was best known for delivering to the niche market of Mac gamers.[1] By the time they'd be done, they'd have expanded to a team of forty people plus testers and act as the flagship studio of Microsoft, Apple's sworn enemy.[3]

To see where Halo got its start, we have to go all the way back to 1997. During this year, Bungie conceived of a proto-Halo after putting a bow on their fantasy RTS Myth: The Fallen Lords. The studio was looking to create something fresh in the real-time strategy space: an experience that would emphasise physics and terrain in a sci-fi package. Soon, they also became concerned about releasing a game that could refill their coffers.[1] In 1998, the company shipped Myth II: Soulblighter, only to learn of a bug in the game's uninstaller that removed every file on the user's PC. Recalling the product had cost this mid-tier developer at least a million dollars.[4]

However, Halo grew away from its strategy roots when engineer Charlie Gough strapped a camera and controls onto one of its tanks. The developers got direct agency over one of the game's jeeps not long after through the same means. They discovered that driving a vehicle in the engine was gratifying enough without the bells and whistles of strategy play. So, Halo settled into a new role as a hybrid shooter-strategy game in which players controlled a faceless cyborg protagonist.[1][4]. Unfortunately, this blend of tactics and action revealed itself to be untenable, leaving the studio to develop the game as a straight third-person shooter.[4]

Halo was first unveiled to the public by Steve Jobs at Macworld 1999. But Microsoft representatives were standing in the metaphorical wings of the conference, watching. They poached Bungie out from under Apple, looking to build out the first-party lineup for their upcoming console: the Xbox.[4] I'd say that leap from the arms of one industry titan to another would be impossible today. Yet, Bungie also managed to wriggle out of their contract with Activision in 2019, still holding the Destiny IP, so maybe a wizard works there. Around this time in Halo's development, the creators started edging the camera closer and closer to its starring soldier. Under the insistence of director Jason Jones, Halo eventually went first-person, with Bungie believing it would let players better embody their one-man army of a main character.[1]

The title's arrival on the Xbox breathed life into Microsoft's console, not just as a singular machine but a lineage of platforms. The existence of the Xbox 360, One, and Series X was contingent on the success of the initial Xbox, and it's hard to imagine that console getting off the ground without Halo 1 and 2. There simply were no other exclusive titles for the machine that came anywhere close to being as popular as Halo, especially in the early days.[4] And Halo didn't just influence the console market. Even two decades later, the storytelling, structure, mechanics, and production quality of AAA games bare genetic markers that link them back to Bungie's brainchild. It is twenty years to the day since the release of Combat Evolved, and I want to do something I've been thinking about for a long time. I want to give a complete review of Halo 1's campaign from end to end, chronicling what worked, what didn't, and crucially, how Bungie's shooter forever changed the face of the medium. This is a Halo: Combat Evolved retrospective.

Pillar of Autumn

There's an elegance to Halo's opening cutscene: it imparts a lot of information without overloading you. It starts by introducing the militaristic faction that humanity has banded around in the future: the UNSC. This cinematic is also where we first see The Covenant: the religious alliance at war with our people. We join Captain Keyes, the no-nonsense commander of the UNSC ship, Pillar of Autumn, and the Cruiser's cool and collected AI, Cortana, as the Covenant storm the vessel. Keyes orders the opening of the "hushed casket", a cryo pod containing our main character and cyborg supersoldier, the Master Chief. "Master Chief" is not a goofy fictional rank but is an abbreviation of the goofy real US Navy rank, Master Chief Petty Officer. Bungie chose that role for their protagonist as its the highest non-commissioned officer rank in the service.[1] They are the most senior person you could imagine in that institution who's still deployed on the battlefield and not sitting behind a desk somewhere.

Bungie is a software house with a rich internal mythos that their games habitually refer back to, and the Pillar of Autumn pays homage to Marathon: a trilogy of shooters Bungie developed for the Mac. We also explore Marathon from the perspective of a highly-armoured gunslinger, and like Halo, Marathon 2: Durandal opens with the protagonist waking from stasis. In Marathon, we work under the UESC, and In Halo, under the UNSC. In both Combat Evolved and the original Marathon, we begin by fending off aliens who've suddenly boarded our ship, with the games in their entireties tasking us with battling extraterrestrial collectives. Both games also have us carry out our tasks with plenty of help from intelligent AI and an on-screen motion tracker.

Combat Evolved's opening, unfortunately, hitches a little as the Master Chief goes through a debug process. The game pauses the action to let us set look inversion and give us a quick tutorial on our recharging shield. Nonetheless, it's not long until you have an Assault Rifle in your hand, a Pistol on your hip, and a sinking ship to save. Traditionally, games going big on worldbuilding don't open without a lot of bootstrapping of their universe and plot. Even today, when a game does land running, it usually backtracks to some sort of explainer soon after. But Halo knows that you don't have to write out every tiny detail for your audience. There's no loquacious story setup performed in this level; the FPS trusts that its players are smart enough to infer all they need from their first-hand experiences. And it starts in media res. We're let loose in a maze of blaring sirens, scattered barricades, and dying marines, so it grabs our attention instantly.

To touch on a related issue, many critically acclaimed films and TV shows have characters stand around educating each other on facts that anyone living in their universe should already know. By refraining from tortured infodumping, Combat Evolved gives us a setting that feels organic and lived-in. Still, the best writing in the world wouldn't have saved Halo if its gameplay was subpar. Fortunately, as our muzzle flash lights the bulkheads of the Autumn, it becomes clear that we're not playing the shooters of old.

Conventional wisdom was that a quality FPS couldn't work on a console, and Halo was busting that myth. There'd been confusion over how you'd allow someone to move their character and reticle in any direction at any time using a gamepad. Halo popularised using the left stick to walk and the right stick to aim. This control scheme was previously employed by Argonaut's Alien: Ressurection and EA Los Angeles' Medal of Honor: Underground, both put out on the PlayStation in 2000. But the scepticism over console shooters extended beyond disbelief that you could map inputs appropriately for them.

It was common opinion that they could only ever be pale imitations of their PC superiors because a control stick could not deliver the accuracy of a mouse, and accuracy was everything in gun-led combat. What's more, a keyboard supports more unique inputs than a controller, and so, it seemed to be the only peripheral that could accommodate the multitude of weapons and verbs found in most late 90s FPSs. Halo utilised a less sensitive control peripheral than the classic FPSs with fewer receptors to let players express their intent. Yet, the play felt as responsive and meaningful as it did in PC action games, if not more so.

Bungie made the FPS fit a console container with a couple of creative affordances. Firstly, an almost imperceptible smoothing of player aim and movement. The code nudges a reticle that's just off of a headshot over a few pixels and makes subtle course corrections in player movement. This input-post processing can largely be credited to designer Jaime Griesemer.[1] These systems sit on the razor's edge between abandoning you to the slight imprecisions of gamepad manipulation and wresting control of the Chief from you. While the Xbox controller can never be as accurate as a mouse and keyboard, Halo demonstrated that that doesn't matter nearly as much as you'd think it would. While we often see entertainment software's job being to execute on the player's inputs directly, Halo shows the worth in intuiting the player's intention from their inputs and acting on that instead.

Bungie's second vital modification to the FPS was a streamlining of player abilities. There was no chance in hell of comfortably mapping every option in one of Valve's or id's shooters onto Microsoft's controller. So, Halo doesn't try to be a game with that many inputs available at once; it finds the right quantity for the input device it's using. A PC shooter might have controls to equip one of ten different weapons and to twist our protagonist's body in a multitude of patterns. In Halo, we can hold two types of grenade and two types of firearm at once, and the only powers we have outside their use is to melee, jump, turn our torch on and off, and that's it. The designers prevent this reduction in player verbs from killing variation in the gunplay partly by allowing us to swap the weapons we are holding for those we find in our environment.

What we see in Halo is a decluttering of the FPS inventory. In other games of the genre, you could have eight weapons strapped to your back and rely on only three of them. With just two weapons to employ, you can't be so wasteful. You also don't have to fumble through a multitude of tools to select the one you're after. You have one off-weapon, and as soon as you hit Y, you're holding it. Changing weaponry is simple and immediate, keeping up with the rapid pace of combat. My only criticism would be that when you have to scavenge for new toys, it can be a little finicky to sort through the pile of them left at the end of a skirmish.

On higher difficulties, the game organically pushes us to conserve ammo and change weapons often, keeping the play from growing stale. Enemies have more health, so we must pump more rounds into them to kill them, potentially draining weapons much faster. The motivation to conserve ammunition is also a motivation to be more precise in our shooting. We need to make every shot count.

The two-weapon system is more restrictive than letting the player amass a warehouse of guns over time. However, it's often restriction that challenges us and forces us to make strategic commitments. Interesting things happen when you're not working with your favourite firearm, just the gun you've got. A subtly brilliant wrinkle in the design is that it's always faster to switch weapons than to reload or let them "cool down". So, we frequently have to make the difficult decision of whether to try and stay out of harm's way while our boomstick catches its breath or whether to switch to a gun that might not be suited for our task.

Notice also that grenades do not fill a weapon slot, so players can always carry them. The availability of grenade attacks is relevant because we can use them to control space and flush aliens out of cover, regardless of whether we're carrying a weapon suited to those purposes. There are two grenades in Combat Evolved: a more traditional Frag that levies fairly severe damage over a wide area and the Plasma Grenade that trades a smaller range for a guaranteed kill if it lands on an enemy. When picking the proper grenade for the job, the player must think about whether they want to focus damage on one foe or many. They must also consider whether they want to risk a throw that would require deft precision or play it safe for less focused damage. There is more nuance to using the grenades than just deciding to deploy an area of effect attack.

While we're analysing munitions, let's have a look at the Assault Rifle and the Magnum. They're the default weapons for this mission and many others. One is a spray-and-pray implement, while the other is made for pinpoint accuracy, offering something for both novice FPS players and those with some experience. The Rifle is a short-medium range weapon, while the Magnum is for medium-long range, so you have all bases covered. The Halo 1 Pistol is fondly remembered for its blunt force. When you fire it, you get this booming sound effect, and if you kill a smaller enemy with it, it will send them tumbling backwards.

There would appear, at first, to be a cookie-cutter strategy for the Pillar, only constrained by how much ammo you have: use the Magnum when an enemy is far away and the Rifle when they're relatively close. However, Halo complicates the decision of which firearm to use when by throwing enemy shields into the mix. You can kill Grunts or Elites, which are smaller and larger enemies, respectively, with a headshot from the Pistol. However, you can only take a headshot on an Elite once you've chewed through their thick energy field. At short to medium range, the Assault Rifle is more effective at dropping shields than the Pistol. You often have to face Grunts and Elites simultaneously, at the same range, and so, are torn between the use of the Rifle or the Magnum.

As we fight only Grunts and Elites on The Pillar of Autumn, this level is a perfect training ground for matching weapons to enemies. However, even with just two guns and two enemy variants, there's a lot of factors pulling you in different directions when it comes to picking your weapon. And, of course, there are plenty of guns besides the Pistol and Assault Rifle to steal from Covenant corpses. The "correct" tool for the job changes a lot based on the details of the current battle. Your strategy is less cookie-cutter and more bespoke, keeping you paying attention to the action and letting Bungie vary encounters. The wealth of tactical agency in Halo's gameplay may be a vestige of its RTS origins.

The Covenants' behaviours also express the personalities of these zealots and establish refreshing combat dynamics we must adapt to. Grunts do not, generally speaking, dodge incoming fire, but if you kill their Elite masters, they'll scatter to the corners of the room. Elites show no such cowardice, ducking and diving out of the way of your shots, and even clobbering you with their rifles. Sometimes, the Elites respond to their shields dropping by screaming to the sky. This outburst suddenly relocates their weak spot but leaves them unable to attack for a split second. From their engagement styles, we can tell that the Elites are skilled and proud combatants, while the Grunts are weak-willed and dependent on their sergeants.

The behaviour of the Grunts and Elites may affect the order in which we eliminate them. There's no perfect strategy here as the ideal player behaviour is subject to our proximity to enemies and the level geometry. Elites are more of a threat than the Grunts, but if there's lots of cover nearby, killing an Elite may motivate their minions to run into these more defensible positions. Engaging an Elite in melee combat might typically be risky, but sometimes our angle of approach makes it easier to get behind them. One punch to the back is also a one-hit kill.

YouTuber Noodle made the neat observation that if you attach a Plasma Grenade to a Grunt, it will run around terrified. So, you can often stick a Grunt with one of these explosives and watch it endanger its own squad. A stuck Elite, however, can charge you, trying to take you with it. There's a risk-reward relationship here, where the closer you get to an Elite, the easier they are to stick, but the more likely you'll get caught in the grenade blast. To add to Noodle's points, if you kill any enemy just before it throws a grenade, the explosive will fall to the floor, creating an immediate hazard for everyone in the vicinity. Useful if you're far away from the grenade but demanding some fancy footwork if you're breathing down that soldier's neck.

The Plasma Grenade is a classic example of Halo's weapons in that it does not create a universal outcome when unleashed on an enemy. The result is affected by who you use it on and when and where you use it, meaning that your patterns of engagement must also change based on context. Again, level design can play a role as you probably don't want to stick an Elite or drop a grenade to the ground in tight quarters, but you might be able to use the same limited space to trap an enemy with an explosive. Because encounters vary wildly based on your weapon, opponents, and surroundings, the designers can change one thing about a combat scenario and get a totally different engagement for you.

I'm not going to let us leave the ship without discussing another core Halo mechanic: the shield. Not the Elites' shield, but the Chief's. This is the design component that launched a thousand recharging health systems. Halo was not close to the first game to include regenerating health; the mechanic originated in the RPGs of the 80s and later saw fame in titles from Ys to MIDI Maze. However, game design isn't just about inventing new things; it's about knowing what pieces fit where and implementing them correctly. It was through ticking those boxes that Halo was able to set the standard for video game vital essence.

Strictly speaking, shields and health aren't the same mechanic. When you run out of health in a game, you fail or enter a downed state. If you run out of shield energy, enemies get a shot at your typically limited HP. These mechanics are also presented very differently: health is the physical fortitude of your character, while a shield is a space-age defensive skin. Some gamers are very particular, even smug, about making this distinction. However, it is important not to mistake the narrative wrapper for a mechanic for the mechanic itself. We also shouldn't get too hung up on technicalities.

Halo does not costume the shield as a form of health, yet the shield plays roles that health does in many other games. Enemy weapons deplete it, and we must preserve it to stay alive. As we frequently have to stay out of harm's way, waiting for our shield to recharge, Halo has slightly more downtime than some other shooters. However, the shield system does solve a problem from earlier FPSs. If the designer doesn't know a player's health value as they enter a room, it's almost impossible for them to set the correct difficulty for that zone. A chamber that is just right for a player on 50 health might be a cakewalk for a player on 100. The same area could be a nightmare for a player on 10. There's no way to adjust a level like that to not exclude someone somewhere on the spectrum of health, warping the difficulty curve and the stage's pacing.

Because Combat Evolved has a max shield value that the player will always enter an area with, the designers have a much better handle on the challenge any one room will pose and can shape it accordingly. Plus, a player can't feel cheated one way or another because they showed up to a standoff with too much or too little health. Critic Doc Burford expounds on how the shield allows us to take risks like socking an enemy in the face: If we know that any damage incurred in combat is semi-permanent, we're likely to be highly cautious in our approach to it. If, however, we know that after a moderate failure, we have a good chance of falling back and recovering our lost stamina, we're more inclined to make bold, spectacular moves on the battlefield. That confident and daring attitude is part of what gives Halo its zest.[5]

With our arsenal of two and our inexhaustible energy shield, we tear a path through the Pillar of Autumn, but it's not enough to stop the Covenant from taking the ship down with them. This opening level establishes a simple truth: when the UNSC and Covenant battle, the Covenant usually come out on top. Us being on the back foot stops Halo from being a one-note power fantasy. The Master Chief is, fortunately, a tough cookie. With Cortana hitching a ride inside his head, he makes a swift exit from the craft and crash-lands on a ring-shaped world of unknown origin: Halo.

Halo

Halo will be our home for the remaining nine levels of the game, and the version of it we see in its eponymous stage is rocky and verdant. This Xbox shooter was not the first piece of fiction to include a ring-shaped organic habitat. Famously, sci-fi author Larry Niven published a book about a habitable circular world back in 1970: Ringworld. However, the concept of a ring-shaped space station can be found in literature as early as 1929, in Austrian engineer Hermann Noordung's Das Problem Der Befahrung Des Weltraums.[6] Bungie frequently keeps us conscious of its ringworld as a physical entity by having its geography conspicuously transform the play. The Pillar of Autumn's level design exists as a complex of corridors punctuated by moderately spacious atria. Such was the design template for the 90s FPS. This second mission marks the series' introduction of expansive landscapes on which to duke it out.

Some shooters before Halo had large outdoor spaces, but they were often relatively featureless, sometimes flat areas with myopic draw distances. Halo has undulating hills and valleys pockmarked with natural setpieces, and they all seem to stretch on for miles. We can majestically scale ridges and experience a 3D relationship with the terrain and combat that wasn't present in many earlier darlings of the genre. The need to think about movement along the Y-axis is why Halo has a jump that catapults you into the air.

The abundant trees and rocks in these outdoor environments mean more places for the Covenant and us to hide, while vantage points allow us to scope out enemy squads and literally take the high ground. Of course, they can do the same. As Combat Evolved's designers lay down surfaces at multiple heights, they're often able to fit more level into a smaller footprint. The fluctuating topography of these maps is a remnant of Halo's gestation as an RTS, one in which terrain was meant to assume a prominent role in the gameplay.[1] It's also a faint throwback to Bungie's Myth, in which units could take advantage of elevated ground.

Modern games often use scale to wow audiences, depict impossible spaces, and even showcase the power of computer hardware. All of which, Halo did; you can see how Combat Evolved acted as a tech demo for Microsoft's first console. However, through upsizing environments, Halo also created new gameplay possibilities. The conflict is not limited to close quarters; battles can take place across a variety of ranges, with weapons to suit each distance. Large plateaus and valleys can also provide enough surface on which to drive a vehicle. For modern shooter developers, there are no changes left to make to environments that open up as much possibility space as Bungie did.

It's unlikely to be a coincidence that the spacious Halo is the mission where the series first introduces its iconic LRV: the Warthog. With a lightweight chassis and two-wheel drive, the Warthog emphasises the shape of the land under it. That terrain reciprocates, spotlighting the handling of the Warthog. The car's back end whips around when turning corners, it exhibits drag as it trundles uphill, and a small ramp is enough to make it take flight. The Warthog achieves such a vivid physicality partly because it is slightly out of our control, at the mercy of its own weight and horsepower. The impression of vehicles with palpable physics was also a core concept in that pre-Halo RTS, and you can see how a whole game could have emerged from this military jeep.[1]

During the level, we can get in and out of the Warthog at any time. The environmental design often prompts us to do so, with huge expanses that the Warthog can motor through in no time and some tight spaces it has no hope of entering. The idea of seamlessly transitioning between vehicle and soldier play was novel in 2001. Just don't let the AI drive. It's not that your fellow marines are any dumber than the average video game NPC of their time; the problem is our reliance on those computer-controlled characters. It's no skin off the player's nose if the enemies are less than geniuses; that works in our favour. It's also acceptable if our brothers in arms make a blunder when fighting alongside us. After all, we're the ones meant to be saving the day. But when we have to place our life in the hands of a soldier that can't drive straight, it gets frustrating. This issue will persist through Halo 2 and 3.

To test our newfound driving and gunning skills, this mission introduces an enemy not present on the Autumn: the Jackal. Short and raptor-like, Jackals typically attack with small arms and hold a shield in their off-hand. You can direct so much raw firepower at their shield that it breaks, but that's an expensive tactic. In a few cases, we can position ourselves to the side of or behind this enemy and get a clear shot at them. Else, a dexterous player can shoot the hand with which they hold their shield, forcing them to stumble, and then go for a headshot or otherwise damage them. Notice that the Jackal doesn't just change up what a headshot means with a uniquely positioned weak spot but also by frequently requiring a two-stage approach in which the target moves. Again, dynamics and unique behaviour come into play as Jackals are the one infantry unit that can block a grenade with their shield and will raise their guard over their head in an emergency.

What's most surprising about this mission, however, is just how much quiet there is. It's not all plasma fire and running down Covenant. Sometimes there are moments where we just get to breathe in our natural surroundings unaccompanied by music. They feel almost like they belong in more recent minimalist exploration games. Think Firewatch or Proteus.

The Truth and Reconciliation

After recovering the first band of survivors from The Pillar of Autumn, we must infiltrate the Covenant Cruiser, Truth and Reconciliation. The aliens have taken Captain Keyes prisoner on this ship. After a level of claustrophobic corridors and one of open spaces, you might think you've seen every configuration that Halo's environments can exist in. However, The Truth and Reconciliation shows a third face to the game. It begins with us exploiting the cover of night to make a raid on the extraterrestrial craft. Direct confrontation is risky, especially on higher difficulties. So, our allies prescribe keeping to the shadows, using a Sniper Rifle to pick targets off from a distance. In the case of Grunts, we can sometimes sneak up behind them and melee them in the back.

Note that if we're hit while aiming the Sniper Rifle, the scope zooms out. This means we can't use it to dig in and one-shot enemies while under fire; we must embody the spirit of the level by finding adequate cover or remaining unseen. Otherwise, the scope will keep retracting, and we won't be able to train the Rifle on distant targets. As we cut deeper into the canyon, "Active Camo" pickups make us all but invisible, increasing the number of positions we can take without drawing fire. This section is also a stellar example of how Halo challenges us to divide our attention when facing enemies. While the Elites always pack a punch, we must also remain wary of Grunts occupying Plasma Turrets and Jackals perching on cliff tops. It's easy to get tunnel vision when staring through the scope of a sniper, but neglect one group of sharpshooters for too long, and they will punish you.

As we approach the Cruiser, the game plays with our expectations, making us believe we have a clear path to its loading elevator before deploying squad after squad of enemies from it. The energy of the level changes as we go from sneaking our way towards the ship to fighting in a wave-based format. When we have dispatched all other Covenant, we face a fierce new opponent: The Hunter. With their Plasma Cannons and skull-cracking melee charges, these warriors can do devastating damage both at a distance and in close quarters. Worst of all, almost their entire front is encased in armour that blocks incoming fire.

Your best chance at felling a Hunter is usually to get behind it, but the further you are from it, the wider the turning circle when you're trying to shimmy around to its rear. At anything more than a moderate distance, the Hunter will turn faster than you can strafe, so you want to get in close. Plus, if you can force the Hunter to take a swing at you, you can one-eighty and shoot the supple meat on its back. The combat now moves from long-range to right in the enemy's face. Again, grenades work differently with a different species: your Frags aren't just there to clear many foes in one blast. Instead, a viable strategy to damage a Hunter's reverse is to throw a grenade behind them.

And, of course, inter-enemy synergy still plays a role. Hunters come in twos, with one covering the other's back to mean there are no easy shots. Tussling with these juggernauts feels like nothing else in an FPS; there is a tense dance that we must commit to to sidle around the Hunter while dodging bolts of fire and aggressive lunges. Unfortunately, you can execute a Hunter with a single Pistol round to the back: a quirk of how Combat Evolved processes headshots.

The existence of the Magnum exploit is unfortunate in that it takes a game that's usually about there being no perfect gun and changing weapons often, and gives you a clear and ideal strategy that encourages you to haul a Handgun all the way through levels. Still, if you want to keep that sidearm loaded, you're going to have to exhaust your primary weapon often, pushing you into collecting new weapons more frequently. A wonderful detail here: you'll notice that the Hunters' orange blood makes it obvious when we're damaging them, even in the dark. Combat Evolved goes heavy on painting the environments with colourful alien viscera during fights, giving us a Splatoon-like agency over our surroundings.

Once we ascend into the Truth and Reconciliation, the tables turn. Now, we're on the Covenant's home turf, and they're the ones using stealth to their advantage. Transparent Elites rush at us with Energy Swords drawn. On Normal and higher difficulties, they can kill the Chief in a single blow, and unless you're lightning fast on the defence, you'll start seeing your marines drop like flies. With cramped corridors and cluttered cargo bays, the ship ups the difficulty by taking enemies we must inch around like Jackals and Hunters, and giving us less wiggle room with which to do that. This area also possesses a lot of verticality. It's not that it has as many ramps and dips as Halo, but we often need to move between floors to get ahead or will take fire from enemies on more than one story at the same time.

In the belly of the Truth and Reconciliation, we get a taste for how alien the Covenant is. Concept artist Shi Kai Wang turned to the strangest creatures of our world: the subaquatic, to find an aesthetic for this army from beyond the stars.[1] Halo has a potently assertive visual identity; you can look at a vehicle or building and immediately know the faction it belongs to. While the UNSC's creations favour straight lines, blocky architecture, and military greys and greens, Wang lent the Covenant a curved, iridescent style, soaked in purple. You can almost imagine the Cruiser swimming out of some deep ocean trench.

Ideally, media uses all its means of expression to represent its characters. If Halo is a shooter, it makes sense to project its themes and aesthetics through its guns. So, not only does the appearance, sound, and behaviour of the Covenant communicate who they are, but so do their weapons. Where UNSC firearms are comparable to our modern-day armaments, the technologies and operation of the Covenant tools are foreign to our species.

Most of our adversaries' guns don't use rounds, and so, don't need to reload. However, they can overheat if their operator fires them too frequently in too small a window. UNSC weapons can generally be used continuously with a guaranteed period of dormancy when the clip runs out. When firing Covenant guns, you can avoid a long period of inactivity, but only if you use them with restraint. Therefore, you don't just know when you're using a human or alien weapon; you can feel it.

Often the firing modes of the Covenant weapons are also eccentric. Halo's Plasma Pistol is comparable to Marathon's Fusion Pistol. While it has a standard fire that can plink away at enemy minions, we can also charge it to release a high-powered blast that drops their shields instantly. This EMP also causes the gun to overheat. Notice that the Plasma Pistol's design encourages switching weapons. We can use it to disable an enemy's shield and then switch to a firearm that can deliver damaging fire to finish them off. The exact dynamic of the Plasma Pistol combo depends on what that other weapon is, increasing variation of experiences. Then there's a firearm like the Covenant Needler, which launches pink spikes at a target that explode after a brief delay. The more needles you can burst on a foe at once, the more damage you can do. Again, we must change our strategy to use this gun, not peeking in and out of cover taking potshots, but getting one extended blast at our opposition.

Having a religious union as the antagonistic force is somewhat unusual for a sci-fi game. It's common for a homogeneous alien faction to have a religion, but not for the enemy to be a diverse group of aliens united by their spiritual beliefs. Halo story lead, Joe Staten, saw how large-scale alliances over human history were often the product of religious ties and speculated that a conglomeration of alien races might also coalesce around doctrine.[1] When we free Keyes, he has news for us, gained by eavesdropping on his captors: The Covenant holds Halo to be sacred and believes it is a destructive implement that could determine the fate of the universe. It feels only too appropriate for an FPS that the object we're ultimately seeking to control, and even the world itself, is a weapon. As the writers will later put it, Halo is "The gun pointed at the head of the universe". There is a refreshingly surreal concept at the core of the games: a WMD with a beautiful and vibrant ecosystem covering its surface.

The Silent Cartographer

In many action games, it's around this fourth mission mark that the urgency evaporates from the plot, but Halo keeps us invested with a time-sensitive, high-stakes problem for the UNSC. The organisation is now in a race against the Covenant to gain command of Halo, and the aliens have better intel on it than we do. Before either party can breach the array's control room, they need to know where that room is, and so, they battle to lay hands on Halo's high-tech map: The Silent Cartographer. Bungie has a knack for poetic names.

The Silent Cartographer is easily the most open of Combat Evolved's levels, yet it's satisfyingly self-contained. The mission is set entirely on an island, with a zippy Warthog to get us from A to B. We can even drive the full circumference of the landmass if we want. After opening on a sci-fi interpretation of the classic "storming the beach" scene, we make our way around the sands. We then weave a route into the temperate heart of the island and venture into metal-lined bunkers nestled in the rocky cliff faces. Notice that we generally move downhill as we spelunk through these bases, making us feel that we are journeying somewhere deep and mysterious to unlock Halo's secrets.

This mission is representative of Halo's level design: scattering objectives around an open environment rather than establishing a linear stage with goals to clear every quarter mile. We fight through hub areas and backtrack where we've already been, and combat feels like something happening in the space rather than the space being contrived for combat. However good your worldbuilding is, the player will not be convinced of your setting if it appears as a collection of levels rather than a universe, and The Silent Cartographer is most assuredly part of a universe. The developers recall that once they got this mission up and running, a vision for the game's design began to take shape. It served as a proof of concept that motivated them in development.[3][4]

One pioneering concept this stage shows off is load-free transitions from interior to exterior. This was rare in games back in 2001, and as we see in The Silent Cartographer, the silky move from inside to outside creates unfettered pacing and a sense of a contiguous environment. What's more, there's a certain subtext to us finding a lot more of Halo underground than we can see on the surface. The Silent Cartographer also stands out as the one mission in which the Halo theme plays.

The music of other levels cribs melodies, instruments, and drum parts from the theme, but during play, The Silent Cartographer is the only level to get the full theme treatment. While Martin O'Donnell is recognised as the Halo composer, Michael Salvatori also aided in fashioning this piece and the soundtrack as a whole. Halo's theme was not composed for the game itself; instead, it came about when Bungie was preparing to debut Halo at Macworld 1999. As the game then had no working sound engine, Joe Staten asked O'Donnell to come up with music to back the demo. Marty and Michael did it with a deadline of just three days, with the former composing the main melody during a single car ride.[7][8]

Just as Halo's title is unusually religious for a first-person shooter, so is its music. Before Halo, major FPSs mostly used intense and contemporary sounds to match their bone-snapping violence. Doom, Quake, and Duke Nukem had all garbed themselves in some genre of metal, and Half-Life was playing off of 90s club sounds. Combat Evolved's theme, and the songs spun off from it, use rousing orchestral sweeps overlaid with singing styles that stretch back to humanity's distant past. Before every adventure film used rogueish, driving strings, they were here in O'Donnell and Salvatori's composition. And vocal forms like pseudo-Gregorian chanting and Qawwali, which were almost unheard of in video game music, headline Halo.

Games as Literature observed that Halo's score sets itself apart from even that of many films of its time by not including horns in its heroic main theme. Listen to the music in movies like Lord of the Rings, Independence Day, or anything scored by John Williams, and you'll hear them use brass instruments for their traditional purpose: to announce something important and celebrate somewhere grandiose. Halo's theme feels stripped back, raw, and historical through its exclusion of horns. Adding to that effect are the tribal drums, which, along with the strings, are often able to force us forward through levels, providing dramatic clashes of instruments as a backdrop for our victories.

Halo's anthem further uses quasi-Gregorian and Qawwali singing to emphasise scale. These are vocal styles designed to echo off the walls of churches and mosques, referencing somewhere and something greater than the listener. In Halo, they can highlight both the visionary volume of the environments and the setting of space. The soundtrack sounds like it's bouncing around these enormous areas. As O'Donnell has said, this music is ancient and mysterious.[8] It is reminiscent of an epoch when instruments were less available, and religion was an inescapable organiser of human culture. It is expressive of the primaeval nature of Combat Evolved's setting, the religious zeal of the Covenant, and the intrigue of its story. It's all part of this series pushing narrative and worldbuilding to the forefront.

It's not every day you hear a catchy monk chant, and no doubt Salvatori and O'Donnell's time in the marketing industry helped them create something that would get stuck in peoples' heads. Prior to this, the duo's most famous composition was for a Flintstone's Chewable Vitamins advert.[8] Marty has said that when writing the theme, he was creating Halo's "jingle".[1] He has mentioned The Beatles' Yesterday as an influence on Halo's opening bars, but a more obscure inspiration O'Donnell has nodded to is 20th-century composer Samuel Barber.[7][8] Listen to the mournful choral vocals at the start of Barber's Agnes Dei, and you'll hear something of Halo in it.

Essential to the soundtrack's push on us is Bungie's sparing use of it. Some parts of the game can actually feel a little sparse in terms of scoring. However, O'Donnell rightly recognised that in most games that have continually looping music, the soundtrack becomes background noise.[9] In Halo, the deployment of the score only at the most emotional moments of the game ensures you're fully conscious of it. It was likely Marty working close to the level designers that created a consummate relationship between the music and level sequences.[7] In fact, the way the senior members of Bungie talk about the game, the same people often wore many different hats during its development, which might be why it's so cohesive.[1][3]

Before Halo, video game soundtracks didn't typically get released independently from the game. However, the demand for a CD of Halo's music was so great that Microsoft complied. Now, every beloved title, and even a few hated ones, are expected to see soundtrack releases. In part through Halo's influence, it's also become normalised for shooters to use orchestral scores. See Call of Duty and Battlefield, among others.

Assault on the Control Room

Now knowing the location of Halo's trigger, we make to wrap our finger around it. Meanwhile, Keyes is off sniffing out a hidden weapons cache. As if to match the increasing adversity of the war, the closer we get to Halo's helm, the more forbidding the weather becomes. The whiplash journey from a tropical island to a frozen wasteland is also a reminder that the ring's nature is engineered rather than organic. Assault on the Control Room pulls its design cues from throughout the previous four levels with tight interiors and gaping canyons. Weaponry includes the short and long-range, the conventional and esoteric, with all of the game's firearms, bar the Shotgun, making a cameo.

This mission does, however, include a new architectural feature: bridges. Slightly wider than a corridor and with metal emplacements across their length, these courseways challenge us to move up steadily, using the cover to buffer ourselves against enemy shots. There is also a Sword Elite who suddenly appears at the end of one of these passes, causing the enclosed space to become a liability. Later, enemies on walkways alongside ours mean that cover in front of us is no guarantee we won't get shot at. We must balance our fire between the road ahead and pests off to one side.

In the chasms below those bridges, we wage epic vehicular battles. Assault on the Control Room is the only level to include the Scorpion, the Halo tank with a devastating and thunderous cannon. After struggling against the ground troops on foot, it's devilishly satisfying to destroy whole squads of them in one shot. But we need all the firepower we can get when the Covenant pull out their best and most bizarre craft to face us. Banshees swoop in low and sting us in the back with plasma pulses, while the Wraith hover-tank shoots explosive munitions in an arcing pattern.

I want to take another moment to borrow from Burford's analysis of Halo: Combat Evolved. A lot of shooters have enemy weapons that effectively hit the player the second that they fire. When that happens, designers punish us for not dodging a hazard without telegraphing that hazard beforehand, which can feel unfair. But the Covenant use munitions that fly through the air slow enough for us to react to them, from the soft homing of the Needler spikes to the bolts from a Plasma Rifle. These perceptible projectiles make the environment feel alive with glowing, flying shots, and allow the player to display finesse in their movement as they dart and flank their way out from Covenant blasts.[5] It's also worth noting that the Elites' and Jackals' classic "dodge" move is built to play with such rounds.

When we don't have all hell raining down on us, Assault on the Control Room plays some of the soundtrack's more chilled pieces. Perilous Journey uses staccato strings and high-tempo drums to create a laidback and playful tension. While, a Walk in the Woods is Halo's music at its smoothest, using ambient synth and a funky bassline to create a sense of effortless and exact operation.

As we finally have Cortana interface with Halo's helm, she tells us that the construct was created by an ancient alien civilisation called the Forerunner. The question to ask now is "how does the game not run out of steam when we've already secured our prize halfway through?". The answer lies in a threat to humanity direr than even the Covenant. A panicked Cortana tells us that Keyes isn't headed for a weapons cache at all and that we must stop him before he releases something much more sinister.

343 Guilty Spark

The murky swamps at the outset of 343 Guilty Spark set the mood for the mission to come. Scattered Covenant ground troops hiding in the fog establish a theme of hidden danger on the horizon. We head into a Forerunner facility which, like Truth and Reconciliation, uses narrow corridors and many two-floor areas, but with the difference that it's now often possible to move directly between the floors. Soon enough, the supply of Covenant dries up, and we're walking eerily empty and quiet territory.

We stumble across a marine undergoing a psychotic break, and not long after, find Keyes' party dead, the floors stained red with their blood. The Master Chief plays back their helmet recordings to learn that they were killed by lifeforms the likes of which we've never seen before. Their murderers were tiny featureless sacks with writhing tentacles that threw themselves at their prey. We'll later learn their name: the Flood.

Fans who played Halo at the time frequently speak of this scene as terrifying. Twenty years on, the reactions of the marines come across as too hammy to produce any authentic scares. The section after also somewhat undersells the Flood by having our first encounter with them go unscored. Still, this mission does convey the sublime threat of this species. Remember that in 2001, memory limitations meant that most games didn't have many living enemies on the board at once. That makes it uncanny when the same aliens you saw besieging the soldiers, the Flood Infection Forms, just keep coming in greater and greater numbers. They are a flood; a sea of them fills the floor in front of us. Halo keeps us engaged in its second act by throwing this new antagonist into the mix and making their AI behaviour less than typical.

Individually, Infection Forms do such paltry damage that it often doesn't matter whether or not you dodge one. In fact, sometimes acting as a punching bag for an Infection Form is the easiest means to get rid of it: a unique strategic choice. But the sheer numbers they arrive in mean they can deliver death by a thousand cuts. And remember, taking any damage while our shield is down causes its recharge timer to start over. So getting hit by an Infection Form creates a longer window of vulnerability that burlier enemies could exploit. Notice that the game could not achieve this effect without a recharging shield system.

After meeting the Infection Forms, we get the pleasure of greeting their big brother: the Combat Form. The Combat Forms are poor shots, but with a mean right hook. All Flood use proximity attacks and always rush towards us. Their single-minded advance means we must constantly put distance between ourselves and them, and backing away from these necrotic abominations can lead us into other enemies. We are forced to rethink our tactics, remain spacially aware, and never get too comfortable in one position.

Narratively, the Combat Forms are the reanimated corpses of other species and why the Flood poses such a menace. They take over living beings and use those possessed bodies to kill more animals, giving them more bodies. One Flood can become two, can become four, can become eight, and so on. Unfortunately, this zombification isn't represented in the game mechanics. It's not like letting our marines die or killing Covenant makes more biomass for the Infection Forms to take over. It's a shame because the game otherwise uses its play to realise its characters memorably.

The nature of the Flood is, however, alive and well in their use of weaponry. While the Covenant have firearms that we can understand them through, the Flood have no weapons of their own; they just steal everyone else's. That creative choice paints them as a parasite and a race even more alien than anything in the Covenant. The species further conveys a horror aesthetic by coming and finding us when we're trying to crouch behind cover, recouping our shield.

On the plus side, their frequent proximity to us makes the Shotgun the perfect weapon for dispatching them. This firearm probably wasn't present in Assault on the Control Room because we will get more than enough use out of it from this level onward. However, using it against the Flood creates tense standoffs where we can't knock down the enemies making a beeline for us until the last second. Perfect for horror villains. As the tone of the combat takes a turn, so does the music. Our encounters with the Flood are coloured by an unsettling audio backdrop. Familiar elements of the soundtrack, like the strings and choirs, become dissonant and tortured. New off-key synths join them to make a shambling, contorted electro-classical symphony.

The Library

Between the Flood and the Covenant, the UNSC is so outclassed that the only relief has to come from outside. 343 Guilty Spark is an AI built by the Forerunner, the same extinct aliens that architected Halo, and he finds us in the thick of danger. He explains that the Forerunner held the Flood on the ring for research purposes; that's why they were imprisoned here. However, Halo is also the sword with which the Forerunner slew the zombie parasites. All we need to do to start Halo is find its key: the Index.

Guilty Spark cryptically refers to us as "Reclaimer", and despite having never met us, views it as our job to activate the ring. While Halo's interiors are mostly cold mineral, you can see something human in them. They use large blocky shapes and a lot of straight lines, just like the UNSC's design. But there's also plenty of ecclesiastical architecture and glowing panels, suggesting a civilisation we have something in common with but that is more advanced than ours.

Halo's subject matter of galactic destruction and armies of the undead could make the story pitch-black in tone. However, it keeps its proceedings light enough for an empowerment fantasy game through playful dialogue and lively characters. It's a Grunt seeing a dropship appear in front of it, and running, squealing, in the opposite direction. It's Cortana watching Master Chief crash a Banshee and then saying, "You did that on purpose". 343 is the most comedic character yet.

Intelligences from advanced alien societies usually have an air of being above it all. They often have a peace and focus that mean they don't worry about the affairs of us lesser mortals. Combat Evolved finds the comedy in that idea, making Guilty Spark farcically immune to panic. He guides us in our war against a genocidal army of the living dead, all the while pleasantly humming and monologuing about protocol on the ring. It's the only respite we get from what is otherwise a high-pressure level.

The Library is notorious, even among gamers who aren't diehard Halo aficionados. Part of its dark reputation is down to it combining with the mission 343 Guilty Spark to form one of those midpoint horror intervals you'll find in so many action games. The unsealing of the Flood is Halo's equivalent of Half-Life 2's We Don't Go to Ravenholm or Uncharted's The Bunker. But The Library has also become a go-to example for directionless, confusing level design.

Much of this archive consists of wide, identical thoroughfares with an exit somewhere before their back wall. Sometimes that exit is a door far off to one side, and sometimes it's a ramp in the floor. However, no two corridors place the exit in the same location, and many paths in the stage are red herrings. Where Halo so often rewards smart tactics, here, there is no method to navigate intelligently. Advancement is a guessing game, and if you guess wrong, the Flood can trap you and flay you to death. When you die, you may find your last save point is further back than you'd anticipated.

See, the code only checkpoints us when we've gotten rid of all nearby enemies, and the premise of this level is there's more Flood than we could manageably eliminate. They appear to spawn endlessly, and then they get in uncomfortably close, so you're often prohibited from checkpointing. It's remarkable how the "Anniversary" version of Halo: Combat Evolved completely eliminates navigation issues in The Library with a simple texture fix. It just draws arrows on the floor, showing you where to go. There's not a lot of subtlety in it, but it's light years better than leaving the player frustrated and aimlessly wandering.

Truth be told, getting hopelessly lost is not an experience unique to The Library. Across the board, Combat Evolved has very open levels and objectives that often spin you around and set you back the way you came. You pursue those goals without explicit and sustained instructions on how to orient yourself. There are no breadcrumb trails, no maps, and despite Halo's reputation, not that many waypoints. It doesn't help that Bungie often replicate the same rooms and even sometimes outdoor landscapes throughout levels. So, yes, The Library can feel like a contrived maze. Still, it's also not unusual to chase your tail in the service tunnels of the Pillar of Autumn, try to work out whether you've gotten turned around in Assault on the Control Room, or find yourself lost on any number of other missions.

Fortunately, when we have a sense of direction, the intense and engaging personality of a level like The Library can shine through. This mission takes that principle of the Flood acting as an organic tidal wave, ups the scale, and dedicates a whole stage to it. These scenes are a slow-motion chase sequence in which our enemies pour perpetually from the walls, forming a moving barrier that is only ever a few steps behind us. Resistance ahead can spell death as there's the risk we will get sandwiched between the two hordes. As mentioned, it's unlikely we'll be able to kill them all; there's too many Flood and too little ammo on the ground. So, we must use a combination of sharp spatial awareness and target prioritisation to make a safe retreat. The designers periodically raise the temperature by making us stand our ground against a wave of Flood while Guilty Spark fiddles with a door.

To make matters more harrowing, The Library introduces the third and final Flood variant: The Carrier Form. Carriers are waddling bags of Infection Forms that explode and release their cargo if they get close to the Chief or sustain injury. These enemies present a few interesting tactical options. Do we fire away at them to clear the level of one more obstacle? Do we dodge around them, tricking them into exploding without expending ammo? Do we use them as red barrels with which to attack other foes in close proximity? All become viable options at some point.

Two Betrayals

As grateful as we might be for Guilty Spark's help, the writers can't very well have an oracle descend from on high and do all the work. Our heroes have to earn their victory. Halo uses a time-tested technique for building an atmosphere of peril. It vends a fake "bottom of the second act", making it look much more pessimistic when you get to the real nadir of the story. If you thought that the prognosis was grim when we unlocked the Flood's prison, you haven't seen anything yet.

When the Master Chief returns to the control room with the Index, Cortana tells him she's discovered that Halo doesn't directly kill the Flood. This galactic pesticide works by killing the Flood's food source: all life, to starve them out. Our priorities and alliances immediately change. To prevent humanity's extinction, we must destroy Halo. When we resolve to do that, Guilty Spark turns against us, his prime directive being to protect the ring and eradicate the Flood.

Even by the standards of Halo 2, released three years after Combat Evolved, this game's plot and characters are primitive. Their wobbly definition is exaggerated by a lack of articulation on the models, which means that when they try to express themselves, they move stiffly and overact. Just watch Cortana try to emphasise the urgent need to obliterate Halo by waving her arms around without moving her fingers. Having said that, the developers shrewdly avoid any grievous animation blunders involving the Chief and Guilty Spark by making them faceless. They can never fail to arch an eyebrow or sync their mouths with the dialogue because they don't have eyebrows or mouths.

And whatever narrative flaws Combat Evolved might harbour, Bungie delivers the cutscenes with attention to cinematography and thoughtfulness about hitting the right beats at the right time. Halo's script and camerawork feel closer to a Hollywood film than that of most earlier computer games. It's also noteworthy that the story gives us more concrete and varied objectives than just "kill the bad guy", imbuing the play with a sense of purpose. That was also one of Marathon's strengths. A supporting pillar in this narrative design is that the storytelling doesn't stop when the cutscenes end; characters continue to converse and interact during levels. The game isn't trying to cram all its exposition and development into three-minute interactions in between each mission. It can make full use of its runtime and retains a sense of character throughout. More commonplace now, a lot less so when Combat Evolved released.

If there's another action game published in 2001 that gives Halo a run for its money, it's Grand Theft Auto III. With GTA III, Rockstar North was able to more successfully execute on many of the goals Bungie had set for Halo. The Scottish-based developer painted a 3D open-world with seamless transitions between on-foot firefights and vehicular thrill rides. In comparison to Halo, GTA III's story is more complex, and its character portraits more humanising. Of course, Halo has GTA III beat on enemy design, weapon design, and visual design, but they are both landmark strides in the staging of video game conflicts.

Despite the skinny profile of Combat Evolved's story, a couple of thought-provoking ideas shine through. Firstly, it matters that it's a mystery tale. We land on Halo with no knowledge of the construct, allowing the game to continually reveal new information about the world, which informs the Master Chief's goals on the ring. It is able to establish a pattern of setting us an objective, letting us achieve it, or at least get within a hair's breadth of doing so, and then presenting some piece of data that causes the Master Chief to change direction. We continually discover that vital nugget of truth that shifts our terminus.

Secondly, in Combat Evolved, and the series as a whole, Halo embodies the theme of events coming full circle. The humans of its universe have apparently left religion behind for a soft secularism, only to find theists and biblical concepts like "the flood" in their spacefaring future. The Flood overran sapient life in the past and threaten to do the same in the present. The Forerunner activated Halo in ancient times, and it may be fired once more. Even the ringworld itself is cyclical, and the play full of elements from Bungie's former projects. This theme of recursion also makes its way into the game's structure.

Development of Combat Evolved was far from smooth sailing, and to make up a full magazine of levels, Bungie had to recycle some maps.[1] To get to this checkpoint in the campaign, we fought through the Pillar of Autumn and then infiltrated Truth and Reconciliation to find Keyes. We then stormed the control room, accessed the Library, and teleported back to Cortana. Now, in Two Betrayals, we will return through the area from Assault on the Control Room. In the next mission: Keyes, we will once more set foot on Truth and Reconciliation to find the Captain. In the final stage: The Maw, we will blast our way, grenades flying, weapons spraying, back through The Pillar of Autumn. This reverse run gives the game a pleasing symmetry and means its ending ties the events up in a neat bow. While there would also be advantages to making every environment unique, a campaign presenting "new content" at every opportunity could not appear as the rounded whole that Combat Evolved does.

It's just, retreading familiar territory gives Two Betrayals a tedious character. Don't get me wrong; it doesn't hurt the believability of the game. You're going to expect any facilities designed by people to repeat the same templates even if those people are ancient alien gods. And when we see recurring patterns in the environment, it helps to project this uncanny characteristic of the Forerunner's creations in which the line between the natural and synthetic blurs. And in the same way that multiplayer maps can provide hours of fun because players make different choices every time, you find Bungie can recycle these campaign levels, mixing up enemy types and placements, and the combat on them will play in a wildly different way. A lot of that is down to the varied enemy design and attention to game dynamics.

However, there are only two levels in between Assault on the Control Room and Two Betrayals. Compare that to the other intervals between encountering the same environments. There are five missions separating The Truth and Reconciliation and Keyes, and eight stages dividing The Pillar of Autumn from The Maw. As synthetic environments tend to, the Forerunner missions reuse a lot of their structures, and we just spent two levels inside the chambers the Forerunner built to enter a stage that has plenty more. Two Betrayals, specifically, is about flying to three identical facilities and disabling a generator at each using the same method. So, during this mission, it feels like a game that has been so inventive and diverse is starting to run out of novel settings and level design.

With such rote tasks, the mission begins to drag. That's especially true when you're encountering constant setbacks. Its icy tundra and cramped refuges are replete with Combat Forms holding Shotguns and Rocket Launchers. Lightning is often dim, screens are busy, and both the Flood and the aforementioned weapons use muted colours. So, Rocket Launchers and Shotguns can blend into the scene right up until the second that their wielders are unloading their salvo at you. You can be speeding along, kicking ass and taking names when one of the Flood runs out of nowhere and takes down half your shield and all your health in one blow. Shotguns are hitscan weapons, so there's no dodging, while Rockets are scary-fast projectiles that can kill you in one hit, which is not much better. Such unforeseeable deaths make Two Betrayals feel unfair on Normal and an exercise in masochism on Heroic or Legendary difficulty.

However, it's not all misery. After being cooped up inside Halo with only the Flood for company, the Covenant are almost a welcome face. You're plunged into the midst of this absolute chaos as UNSC, Covenant, and the Spark's Sentinels all fight it out against each other. Halo gets a lot of mileage out of letting you stumble on the armies fighting amongst themselves. That they have their own military concerns and don't just spend all day standing in a room waiting for you to show up makes them feel more real. Again, see Marathon for where Bungie previously developed this idea.

Later, Two Betrayals will pull its opening trick in reverse, as it surprises us with the Flood after a clean run of Covenant. And look at how the design forces us to adjust our aim with all these different enemy types in play. Not only have you got those weak spots on the Covenant to seek out, you have to aim up to hit Sentinels, at about shoulder height to headshot Elites, roughly knee-height to nail Jackals and Grunts, and below that when Infection Forms crawl in. Halo is challenging you fully in each of its three dimensions. This is also the mission with the most verticality, this time bringing it to the vehicles. Flying our way to our objective is a refreshing means of self-transport, and having to drop our shield to disable the generators leaves us on the pulse-pounding edge of safety.

Keyes

By throwing a wrench into Halo's power grid, we temporarily prevented Guilty Spark from firing it. Still, the only way to guarantee humanity's continued existence remains to destroy Halo. Cortana has a plan to do just that: detonate the fusion reactors on the crashed Pillar of Autumn, and break the ring. However, the Autumn's computers won't authorise that without Captain Keyes' security codes. Cortana tracks his ID tags back to Truth and Reconciliation.

In one of Keyes' most memorable scenes, we snake through a Covenant ship to encounter a gaping hole where the hull should be and a pit of coolant far below. A wave of Flood charges us from behind, forcing us to make the jump into the liquid. Much of the early level consists of pools of glowing green, which we can hide in if threats on the surface are getting too overwhelming. Beyond that, the mission has us take many of the same narrow, curving paths leading to the Cruiser again, but with less illumination. The lack of a Sniper Rifle and the ceaseless proximity to the Flood refocus the area around close to mid-range fighting. Inside Truth and Reconciliation, we find a testament to the ruinous influence of the parasite: They have infested and destroyed the Covenant's former flagship, leaving the troops running scared.

Truth and Reconciliation is, once again, a lot of tight corridors, but that's a greater liability on this return visit. Not only are Flood spilling in from all angles, but we must also contend with one of Combat Evolved's favourite toys: explosives. If a Carrier Form bursts in one of those corridors, or a grenade goes off, or a Grunt's methane tank ignites, it can start a chain reaction of detonations that does spectacular damage. Dying to one of these fireworks shows feels a little unforeseeable, but you can also strategically trigger them against the enemies. These chain reactions are one of the most invigorating sights in the game.

When we find Keyes, the Flood have taken him. We pull a chip from his brain, retrieving the codes and mercy killing him one fell swoop. The void where the inside of Keyes' head used to be is actually pretty disturbing in the Anniversary version.

The Maw

At long last, we are on the home stretch. Without many Rocket enemies or walls of Flood to get trapped between, The Maw is manageable to a degree that the last three missions weren't. But it's not exactly a day at the beach either. The Pillar of Autumn has been overrun by the reanimated marines who perished in the battle with the Covenant. These resurrected servicemen are a macabre reminder of who has been lost in the war over the array. After Keyes, they're also an indicator of how the UNSC and the Covenant are equally susceptible to the Flood. They'll take over a human or alien ship all the same. The title of this level calls to mind the insatiable consumption of the species.

By the time we make it to the bridge, 343 Guilty Spark, the Covenant, and the Flood have pulled out all the stops to halt us in our tracks. Sometimes you can hide in a maintenance tunnel while two of these factions butcher each other, but most of the time, you're surrounded by every enemy in the game's bestiary. Yet, there comes an exciting anticipatory point where it looks like we can turn the tide. We take a trip to the Pillar's armoury, where we load up on Grenades and Rocket Launchers. These explosives are powder in the kegs we're going to blow in the engine room.

Breaking the Autumn's reactors could feel like nothing more than shooting enemies near a new objective. Instead, the developers make it come across as the process of sabotaging a mechanism. For each engine, we must extend a metal strut, stand on it, and fire rockets or throw grenades into a vent. The means by which we destroy the engines entwines with their engineering. All the while, both the Flood and Sentinels try to execute us. Oddly, this section also pushes us to learn the crouch jump. It's a lot easier to get around the engine room if you know how to do it.

With the Pillar about to go up in flames, we reach perhaps the most famous scene of the game: the Warthog run. Halo would later become known for its linear vehicle action sequences, and this moment, more than any other, presses them into the clay of the series. The undulating waves of the ship's tunnels make for the most stupendous jumps we can achieve in the Warthog but also the maximum chance of tipping over. That's a panic-inducing situation to be in because we're racing against a timer. The dynamic between our avatar and the enemies changes entirely during this sequence as they move from being a source of incoming fire to being obstacles to dodge. The explosive Carrier Forms, in particular, shine in their dual purpose of flipping our vehicle.

Many games choose to end with the greatest challenge they can muster, and relief comes with conquering that challenge. But Combat Evolved doesn't want us to spend our final moments throwing ourselves endlessly against a brick wall; it wants to go out on a sequence of tension but one that has forward motion. Something not stuttering and inscrutible, but daring and heroic. Two final times, Halo pulls the trick of yanking our objective that bit further from our grasp, prolonging the tension.

Our destination is a bridge from which the pilot Foehammer can pick us up, and a UI marker tells us exactly how far we are from our goal. There's enough time on the clock for us to reach the extraction point with plenty of breathing room, but when Foehammer arrives, a Banshee pursues her craft and shoots her down. Thinking quick, Cortana locates a jet we can flee on, but it's more than a kilometre out from our position. The ratio of distance to time is now considerably less generous. At the very end of the track, we reach a wall of barrels that forces us to abandon the Warthog and run for our escape plane. We have little time left on the clock, and we're going slower, maximising the stress. The designers are playing with us a little; the trigger to exit the level is closer than it looks. If we can reach it, the Master Chief and Cortana break free of the ring's gravity as the Pillar of Autumn goes critical.

___

In 1999, a group of game developers and branding agents gathered around a whiteboard in a Chicago office. On that board were potential names for Bungie Studios' sci-fi war game set to release on the Apple Mac. When they picked the name "Halo", they were forced to modify it by a publisher that believed the public would not associate it with gripping and forward-thinking shooter design. When its sequel released three years later, it did so without a subtitle because, by that point, there was no confusion in the gaming community about what "Halo" meant. The title had become synonymous with diverse, thoughtful play, rich worldbuilding, and ambitious action sequences. This is all without talking about it having the best multiplayer you could find on the Xbox.

Even today, Halo's play and visual design leaves many new AAA shooters in the dust. We see the same gun archetypes recycled between all the experiences, we go up against enemies who all have the same weak points, or at least, don't have complex combat dynamics. Strategy is reduced to using the right gun at the right range and hiding behind cover at predictable intervals. Too often, action campaigns are about just getting to the next area or picking up the next McGuffin without any meaningful shift in our perspective. Halo: Combat Evolved is something different, something greater, with its reactive enemies that challenge us to play intelligently, its truly alien weapons, its beautiful dance of combat, and its purposeful narrative.

It's therefore surprising that after the original Halo, the development of a Halo 2 was not assured. While designer Jaime Griesemer talked about his fellow employees' hunger for a sequel, director Jason Jones didn't like follow-ups. Composer Martin O'Donnell didn't see another Halo in the cards, designer Paul Bertone went off to work on another project, and art lead Marcus Lehto doubted that Halo would become a series.[1]

At the end of Halo 1, the ring shatters in response to the nuclear blast from The Pillar of Autumn. The destruction of this circular installation is symbolic of the UNSC preventing history from repeating. They stop Halo firing and life in the universe meeting its end as it had before. With the annihilation of their titular setting, Bungie, too, looked to be cutting ties with Halo. But like the Forerunner, the studio had built something bigger than itself, something that would guide its destiny.

In the final seconds of Halo: Combat Evolved, the Master Chief looks out across the stars, surveying the wreckage of the once-mighty ringworld. Soulful orchestra fills the background. Cortana whispers in his ear, "Halo, its finished", but in his characteristically gruff voice, the Master Chief responds, "No. I think we're just getting started". Thanks for reading.

Sources

- The Complete, Untold History of Halo by Steve Haske (May 30, 2017), Vice.

- Seven Steps to World Domination by Bungie Studios (September 25, 2007), Halo 3 Legendary Edition.

- Halo: Combat Evolved Developer Commentary by Bungie Studios (September 25, 2007), Halo 3 Legendary Edition.

- O Brave New World by Bungie Studios (August 4, 2011), YouTube.

- The Unusual Excellence Of Halo's Most Iconic Level by GB Burford (September 5, 2014), Kotaku.

- Noordung, H. (1929). Das Problem der Befahrung des Weltraums: der Raketen-Motor. Richard Carl Schmidt & Co. (p. 137).

- Just the Right Sense of "Ancient" by Carlson (2007), Xbox.com.

- IGN Unfiltered Interview: Halo and Destiny Composer Marty O'Donnell by Ryan McCaffrey (March 24, 2016), IGN.

- Donnelly, K.J., Gibbons, W., Lerner, N. (2014). Music in Video Games: Studying Play. Taylor & Francis (p. 125).

All other sources are linked at relevant points in the article.

Log in to comment