(If you have not played The Walking Dead up through episode three, do not read this. Spoilers abound!)

We’re now more than halfway through what’s hopefully the first of many seasons for The Walking Dead from Telltale Games, but even if this is the only season we ever get, it’s been a hell of a memorable one so far.

It’s been a few weeks since we spoke with Telltale about the series, in which we talked about the moments in each episode where the player is handed a decision about the death of a character. There are plenty of other weight decisions in The Walking Dead, but the moments where a life hangs in the balance tend to be ones that stick around.

With the Gary Whitta-penned episode four, Around Every Corner, not far off (no, I don’t know when, but it’s very soon), it seemed like the right time to sit down with Telltale to reflect on episode three, Long Road Ahead.

That moment with Duck is starting to come back to you now, right? Damn. Damn.

I recently chatted with project lead Jake Rodkin (co-project lead Sean Vanaman was busy with a recording session), designer Harrison Pink, and director Eric Parsons about those moments and more. The team has taken great joy in watching YouTube playthroughs of the last episode, especially when players are confronted with Carley’s death.

“Whenever a new one of those comes out,” said Rodkin, “it immediately gets sent [around] and you can see it on everyone’s computer. ‘We got another one!’ We take a fair amount of thrill watching people who are hit as hard by that one, by the deaths that are going on in this game.”

The tonal shift between episode two and three is significant. Episode two is akin to a horror film, with our heroes pitted against a suspicious foe that turns against them. In episode three, the team didn’t want to release the tension, but focused on pressing a different set of buttons. The player had much less control over who lives and died, and instead had another set of challenges.

“Arcs are beginning and ending all throughout the series,” said Pink. “[With episode three], it’s the episode where many arcs ended and some arcs began. It was a conscious decision to say ‘alright, in this episode, you won’t get any control over any of that stuff.’ But the idea that a lot of these things in world are out of Lee and the player’s control and this is just how the world is is a conscious decision for sure.”

It’s also an episode where early design decisions made became more entrenched. The Walking Dead often allows players to say nothing, usually represented with an ellipses (“...”) as a dialogue choice. When asked to make a decision about the future with Clementine, 4% of people were totally silent.

“In three, I consistently had people coming up to me and say this was the first time they just really didn’t know what to say,” said Pink. “Especially with Clementine, when she asks these really difficult things about what’s going on in the world or what we’re going to do and all sorts of stuff like that.”

One moment of Telltale catering to the whims of passive players was a moment where the player, as Lee, could choose to be engage in a fight with Kenny aboard the train. Then, for whatever reason, they could also back down. The sequence Rodkin describes next never happened to me, and, for a while, I thought he was joking.

“When you’re in the train car with Kenny and he’s trying to get you to fight him,” said Rodkin, “if you just dilly-dally and don’t confront Kenny and you just keep trying to play it down the middle, he eventually throws you out of the engine cab and back out onto the walkway. When you go back into the box car, you realize you’ve spent so long doing jack shit with Kenny that Duck has already died, turned, and killed everyone in the train, and kills you. Apparently it’s referred to as the Duckpocalypse.”

I’ll have to go back and try that, but that’s for another day. Let’s kick things off with the episode’s first big decision.

GB: When the episode opens, the first one you’re presented with is a fairly classic horror trope of “do you let this girl continue to scream and distract the zombies while you loot and plunder, or do you take her out?” This one actually ended up 60/40, so while not 50/50. The vibe I got from it was the game telling me “you should just leave here. C’mon, she’s gonna die anyway.” I’m curious how much of that was my own projection.

Rodkin: For me, I actually always got the opposite read.

Pink: Yeah, Kenny tells you to leave her.

Rodkin: At that point, especially when we were working on episode three, I had just come off of working on episode two, and kind of had gotten tired of Kenny. Kenny telling me to leave her personally made me want to say “go fuck yourself.” I don’t know if that was the intent or not in that scene, but me personally, I was feeling a little overexposed on Kenny, so him telling me to do anything made me mad at him. For us, it was a little bit of--if you put a video game crosshair on top of a character in a video game and give you a shoot button, how many people aren’t going to shoot? We’ve thought about it in terms of the dog who’s trained to sit there salivating while there’s a bone resting on its nose, and that didn’t quite play out in that way as much as we thought. It’s probably good. I think we thought everyone would shoot that girl.

Parsons: The balance we were hoping for was the instinct to pull the trigger when there’s a crosshair on a person’s head versus somebody behind you yelling “don’t do it, don’t do it, don’t do it!” I guess it got sort of close.

Pink: I remember it being somewhat different way earlier. I think it was this exact point of “if you give someone a gun, they’re going to want to shoot it in a video game.” And making sure that didn’t seem like the right [choice]. Obviously, we don’t want there to be a right or a wrong choice, but what is it that the don’t shoot her choice means? What does it mean to Lee? What does it mean to the player? We definitely sat and spun on how to make sure the not shoot her [option] actually felt like a real choice, and it wasn’t just Kenny going “don’t do it! That’s a bad thing to do! You should let her escape!” but making Kenny more pragmatic. ”If we leave her alive, this is what it will mean to us, this is what it’ll to our survival. It’s better for our survival.” But, then, Lee sort of being the more emotional side. “Well, we should put her out of her misery.” It’s the emotional versus pragmatic, which always leads to really interesting choices.

GB: When these moral quandaries come up, it seems the game’s very deliberate to make sure the characters aren’t by themselves, they’re always with someone else. It seems to serve a dual purpose. A, it’s more interesting when there are more opinions. B, it allows you guys, as designers and writers, to voice both viewpoint the player finds themselves presented with. If it was just Lee trying to figure out if he should shoot that girl, it wouldn’t be nearly as compelling if there wasn’t Kenny to the side.

Rodkin: I think if we get to a point where Lee’s going back-and-forth with himself, the game might have gone to a weird place.

Rodkin: I don’t remember where I read this, but it was about stores that started putting a picture of a set of eyes on the front of all their cash registers, and they noticed it reduced shoplifting.

Pink, Parsons: [laughs]

Rodkin: People act differently when they think they’re being watched, and that’s really interesting. Especially with some of the stuff we’re doing in episode four, it’s come up a lot, actually, in meetings and reviews for these things. When is someone watching you? When are you acting alone? It’s a thing that we ask ourselves a lot across these different situations of “how is the player going to feel in the game if someone is standing over their shoulder watching them do this?” versus “are they thinking there’s no one there and they’re going to get a way with it?”

In episode two, we talked about that when you kill that brother with a pitchfork, and the camera suddenly whips over and shows Clementine watching you. People feel so differently about it when they think they’re alone in the barn versus someone is there who matters.

Pink: That guilt shift is really interesting to see. Now, everyone is really paranoid that Clementine is sneaking through to watch them. Playing through episode three, there were tons of decisions where [you go] “if I’m alone, I’ll pick this, but I don’t know if Clementine is going to whip around and show me Clementine again, so I have to consider if she’s sulking in the shadows watching me do this stuff.” It’s really interesting. Even if she’s not, even the threat--well, threat is the wrong word to use. Even the idea that she could be nearby and observing this, even if the camera’s not showing it, really makes people second guess. “This the right decision for now, but I don’t want Clementine to see it, so what does it mean to Lee and me?”

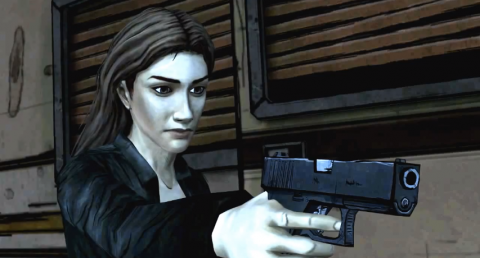

GB: The second major moment is when you have the unfolding conflict between Carley, Lily, and Ben--or Doug, depending on your decisions. The shock value of that moment is pretty incredible. I turned off the notifications that tell you when a character is impacted by a decision, but I was watching the different YouTube playthroughs, and realized the game says, just before Carley gets shot, “Carley will remember that.” Then you fucking kill her! I have to imagine that was a very deliberate choice to have one last sleight of hand.

Everyone: [laughs]

Rodkin: That was kind of choice notification trolling on our part for sure. I didn’t know that was there because I also don’t often play with choice notifications on, but I was really happy. I thought that was a really good use of that system to pacify people for a half-second longer than they might have otherwise been because it goes against what was going on. It’s the weird game UI version of the Joss Whedon thing where he puts a character in the credits of Buffy the Vampire Slayer two episodes before they die.

Pink: I remember putting that in. Even with Katjaa, the stuff with her and giving her water for Duck, it says “she’ll remember that” and she’ll appreciate your kindness. I thought it would be really weird [to not have it]. It’s such an emotionally charged moment. To not be getting feedback that people are remembering would just feel dead and weird and suspicious. I don’t think I put that in there to troll everyone. I felt that if I didn’t know what the story was going to go, this is where I would put in a choice notification with Carley remembering stuff, so I tried to play it that I was ignorant of what was going to happen after 10 seconds of gameplay. You just said something really mean to Carley, and and she goes “What the fuck, Lee?” That’s true, Carley is going to remember that. I don’t think it was a “ha ha, I’m going to get the player with this!” but a thing where you’ve built the player to expect these notifications to pop up, and what that’s going to mean going into further episodes. I don’t think that was the original intent, but I’m glad that it shook out like that.

Rodkin: I’m actually really glad that it went in there. I feel like act one of the game, for people who know how these sorts of stories work, when Duck suddenly becomes a wacky crime investigator and Carley plants a kiss on your cheek, if you know what’s going on, you know these characters are going to eat it by the end of the episode because they just became nice to me. I like that the choice notification, for a lot of people, was maybe the moment where their initial suspicion was gonna be proven true.

Pink: I wonder if that’s where people all thought they could save Carley. Everyone at PAX came up to us and said “seriously, though, how do you save Carley?” Maybe that helped [make people think] “there’s gotta be a way to save her, there’s gotta be!”

GB: I was reading through the comments section of an IGN story, and there was this really long discussion over “well, they wouldn’t have put that in there unless there was some combination of dialogue choices to save her.”

Rodkin: Yes. [laughs]

GB: Another thing that struck me as interesting was how the game plays with the time mechanic. If you dilly-dally on making a choice, the game will either make a choice for you due to a timer or it’ll happen in the background as a way of surprising you. That’s what ended up getting me in the moment with Carley. I was immediately convinced that “oh, if I’d just done this a different way, I would have saved her.” Because I chose to be indifferent, this was a moment where the game said “go fuck yourself, you chose to not take a side, so we’re going to choose one for you.”

Rodkin: The Carley choice is definitely a choice where Carley--or Doug, if Doug’s alive in your playthrough--is a pretty heavy fixed point in the story. It’s a place where we had this trade-off of the mechanics of “do we support a character alive for a while, or is is more interesting to us to say Carley or Doug dead is a fixed point in the story because what’s interesting is using that as the mechanism to put the characters into a new and interesting place and move everything forward.” I’m having trouble phrasing what I’m trying to say.

GB: What happens after this, and as the setup for Duck becomes pretty obvious, you’re basically pressing reset on a lot of these characters. A bunch of the hangups they’ve had for the last two episodes no longer exist, and you can make this clean break to a new characters, new sets of challenges.

Rodkin: It’s safe to say that their short-term effects maybe had a reset hit, but I don’t think we’re wiping the slate on characters, even if it seems that way. In the course of episode three, everybody gets a pretty heavy jolt because of what happens, but over the rest of the season, a lot of that stuff--characters have time to deal with it in the context of everything else that’s happened. It may feel like in the short term that these guys got knocked pretty hard, but that’s not to say what happened earlier isn’t going to come to bear on the story later on.

For us, with Carley, we knew it was going to be a fixed point in the story, but we went out of our way, or at least tried very hard, to make sure that even though that point was going to be the same--Carley was always going to get a bullet in her head--the things that you did and the things that you said leading up to it really make that feel unique to you. Like you said, “I felt like because I was indifferent, Carley got shot.” I know that you can, then, rewind and find out “oh, because you did it a different way, Carley got shot,” we still want to make sure that moment tightens itself up around the choices that you’ve made and the way you’ve been playing so that when you get to that moment, it still feels like it’s your own, even though Carley will always eat it. She probably had it coming, not matter what!

GB: Even though my indifference made me feel like I had sacrificed Carley, my indifference continued because I refused to leave Lily on the side of the road. It felt like the game, then, was deliberately saying “well, if you’re going to continue to be indifferent, we’re going to let this bite you in the ass again because she’s going to take your van.” It’s a situation where, yeah, I can go back and look at how it can play out, but of my own playstyle, at least in the very moment, it feels real.

Rodkin: That’s very much the way we think about it when we make these. Given that we know there are some things that are going to happen no matter what, we want it to feel like “if the player did this and this and this, what is it going to mean when this happens?” Even within those fixed points, when the characters actually discuss them and contextualize them in the game, you would probably find them surprisingly different in a few places. Even though the big events don’t change, all of the flavor around them is [different]. We thought to ourselves “what would Patrick Klepek do?”

GB: As most good game developers do.

Rodkin: We tried to write just to you! But, hopefully, I could be doing this interview with a lot of different people and use that same joke and it would work.

Everyone: [laughs]

GB: I’m going to start going through every interview you’ve done in the last six months.

Rodkin: I’m going to blow your mind in episode five when Clementine turns to the screen and says “Hello, Patrick.”

Everyone: [laughs]

GB: The way the last big moment plays out is not telegraphed, but the moment Duck starts to get sick, you know where this is going. You’re not sure if this is going to play out in this episode, but you know things are going to go bad, decisions are going to have to be made. I’m curious how you guys figured to tip your hand on Duck being sick. From that point, it gets the player mind rolling in a certain direction.

Rodkin: We’ve known since before we wrote a single line of dialogue in episode one that Duck was going to get bit and die within episode three. That was one of the really, really early pieces that we had. Episode two’s lynchpin moment that we knew was there from day one was Larry getting his head bashed in a meat locker, and we knew that episode three was going to be all about everyone being super bummed and, over the course of the episode, Duck was dying. As far as within the specifics of episode three, I don’t really remember when we started figuring that out.

Pink: Honestly, the way that played out was pretty fluid. Not all the way to the end, we locked it down at some point, but there was a time [where] the amount of time that passes between the initial bite and the discovery of the bite to the group and, obviously, the event in the clearing when you have to make the decision--how all this played out was fluid, making sure it had its own place in the story. We didn’t want it to be Carley got shot in the head, oh man! Duck got bit, oh man! We definitely wanted to make sure each of those events could emotionally wrap up, and give time for Lee and the player to digest them and go “holy crap” before we smacked them over the head with another insane thing. We definitely moved them around to make sure each important thing had its due. It took a while to get right.

Parsons: It also didn’t change all that much. All those pieces were pretty well established.

Rodkin: We knew we wanted all those things to happen, but the order of...Duck gets bit, then the RV breaks down, then you discover the train, then Duck gets killed.

Parsons: I think there’s post-it notes shuffled around somewhere. [laughs]

Rodkin: When is Duck bit? And how do we present that so that it’s feels it’s something that starts pressing on your mind, but isn’t an immediate emergency, so it still feels like it’s okay for Lily to have her crazy breakdown and shoot someone. And it also feels okay to wander around and get a train going, and only once you’re on the train does Duck take his final turn. Having that order of events...we freaked out about that quite a lot over the course of development, and there were probably earlier story structures where it was just deal with Duck then deal with Lily or deal with Lily then deal with Duck. Getting all that stuff interwoven was actually a fair amount of story juggling.

Pink: We definitely had a discussion about how we allow the player to wander around a broken train while Duck is dying and feel okay. [laughs] That was definitely several days worth of a conversation.

GB: In terms of the actual moment, where the player can choose to take care of Duck for Kenny, was it always the intent that the player would have control over a reticule?

Rodkin: The short answer to that is no. Duck’s death is actually a scene [that] we knew from the beginning was going to be the biggest moment in the episode, or, at least, was the one we had been thinking about the longest. Actually, because of that, it meant for a really long time, it had a tendency, as a lot of moments that have been around for a long time do, to just become auto-piloted. It existed unchanged in design for almost a year. We started the story for this a ways before episode one, and it wasn’t actually until we started getting the game built we realized Lee, as a completely passive observer, was not actually all that interesting.

Pink: Originally, you do pretty much the same thing, but once they go off, you just hear it happen. Obviously, the discussions you had were mostly the same, but once the actual event happens, it was very much [that] Lee wasn’t a part of it at all.

GB: It’s handed off to a cutscene, and the player just implies everything else.

Pink: That’s how it was for a long time.

Parsons: It was also a lot more vague. Katjaa and Duck walk out into the woods, and you hear a gunshot and nothing happens for a second, and then zombie Duck walks back out.

Rodkin: That was it!

Parsons: And then Kenny gets sad and everyone gets back on the train, and that was the end of the scene. The two big critiques, now very rightfully so, were that “wow, that was way too vague, and the player has nothing to do in this scene.” So all the stuff about making the first decision of who is going to go out and do this, and the second decision about who has the gun in their hands, all came relatively late compared to the knowledge that Duck was going to die.

Rodkin: That’s a pretty good example of [where] we knew that story moment was there from day one, but how it actually plays out in detail got pretty heavily shuffled around. We’re pretty happy with how that turned out, but it’s a pretty big overhaul from what was originally just a sad cutscene moment, where you could talk to Clementine a little bit, and then Kenny cried.

GB: When I was presented with the reticule, it wasn’t as easy as “oh, okay, I guess I’ll just pull this trigger.” It was a lot different than the axe moment, where a lot of people were like “oh, hell yeah, I’m gonna chop that leg off!” At least if you’re taking the game semi-seriously, this is a moment of pause. I played the game co-op with my wife, and we sat there for a while thinking, “well, maybe if we wait long enough, he’ll turn into a zombie and we’ll feel less bad if he’s attacking us. Otherwise, yeah, he’s getting sick, but he hasn’t undergone the transformation into this evil creature.”

Rodkin: That’s actually a detail that we also talked about and went back-and-forth on a lot. Where we ended up settling was that we thought about letting Duck go to the point that he turns, but that actually came off as “can’t we spare players and let Duck turn?” And the answer is no because you’ll feel less bad because you’re killing a zombie. Where we ended up landing was that if you do wait long enough, Duck stops breathing. When he stops breathing, you still get a second to pull the trigger if you want, but if you wait too much longer, they just say “we can’t do it,” and leave, which very few people did. And then no one shoots Duck.

GB: When I was looking at the stats, it only has Lee shooting Duck or Kenny shooting Duck, and didn’t realize there was another option.

Rodkin: It’s another one where there’s a very small percentage of people who do it, but the game does support it. If you wait long enough, either Kenny or Lee says “let’s just go,” with Duck just laying there versus zombie Duck, who is now amassing a horde of zombies on his quest for world domination.

Pink: There’s a lot of people who say “I don’t like this character, I’m not going to feel bad when he goes” and to the extent of “I can’t wait to kill that kid!” But when you actually put a gun in someone’s hand and you’ve said “Kenny, I’ll do it,” a lot of people that I spoke to said “I was ‘no problem, I can handle this’ until the reticule came up and I went ‘whoa, this feels a lot different than I thought it would.’” Or they would shoot, and then walk away saying that, either right before or right after. “I thought I was totally okay doing that, but actually being presented with the reticule and this little sad boy’s face, I thought it would feel like a video game, and I felt not the way I thought I would about that.” That was always really interesting to hear.

Rodkin: I’m sure there’s always a silent contingent somewhere that doesn’t mind blowing away Duck’s face, but we hear pretty often from the people who have suspension of disbelief going on to the point that it actually matters that they’re pointing a gun at this little kid. It’s kind of cool.

Parsons: I got more confident about my ability to execute this scene after hearing feedback from episode two. The people that in episode one who said “oh, man, Larry, the first chance I get, I’m taking that guy out,” and when episode two rolls around [they said] “oh, man, I couldn’t do that.” Hearing that, I was like “okay, I think Duck’s safe.”