Broken Glass: Stories Untold and Anthologies

By gamer_152 5 Comments

Note: The following article contains major spoilers for Stories Untold.

If you've read a lot of sci-fi and horror literature, you'll have sifted through plenty of short stories. In horror, a shorter story length allows an author to push their characters to the end of their psychological and mortal rope faster. In science fiction, banging out a lot of short stories instead of one long one permits a writer experimentation with many different cultural and technological hypotheticals. Traditionally, publishers haven't sold these works separately because printing, binding, storing, and shipping a book with one short story in it didn't make economic sense. An alternative was to collect a series of micro-novels into a single tome, grouping them by author, theme, or mood, and that's how we got written anthologies.

By contrast, video game anthologies haven't been as prominent. If you're thinking of an anthology in video gaming right now, then chances are it's a collection of classic retro games ported to a modern system rather than an original package. There were a lot of those "100 Games in 1" cartridges, and they did contain original creations, but they tended to repurpose masses of code and assets between their games and were not taken seriously by video game connoisseurs. We have Warioware, but its "microgames" may be short enough to disqualify it as an anthology. ISLANDS: Non-Places is an anthology, and none of its content has appeared in works prior, but you'll also notice that it doesn't have an explicit story; narrative anthology games are one in a million. What Remains of Edith Finch and McPixel come close to being narrative anthologies, but they're more like sets of discrete scenes that don't ludically link back to a "core gameplay", but still narratively do, which means we can't count them as story collections.

The big reason that anthologies are more prevalent in literature than in game dev is that such compilations are reliant on creators authoring original characters, settings, and MacGuffins, and then five to ninety minutes later, throwing them away and starting the creative process over again. Someone working in literature can take that task in their stride as creating whole new worlds doesn't come with a lot of burdensome production work; it just means typing out a new set of words on the page. For a game developer, crafting new worlds means fabricating unique models, animations, audio assets, and likely code. Throwing away and replacing all of your work in each of these areas every sixty minutes or so could incinerate enough production resources to kill the whole project. When you play video games, you see the same crates and barrels everywhere, you hear the same gunshots and audio barks all the time, because it's only through reuse of content that such a strenuous undertaking as building a computer game becomes viable. The anthology format would upset that cycle of reuse.

This isn't just a problem for entertainment software, but any production-intensive medium. Charlie Brooker, the creator of horror sci-fi anthology Black Mirror, has repeatedly spoken about the challenges of producing each episode from the base up, having to hire new actors, make new props and costumes, and film in new locations each time, unable to transfer over the actors, props, costumes, and locations of previous chapters. But a significant difference between TV and video games is that gaming audiences place a premium on "value for money" because unlike with literature or television, the price of entry averages much higher. A TV viewer is going to pay practically nothing to watch a whole series of Black Mirror, so its producers don't have to worry if production limitations mean customers only receive three episodes per series. An indie developer selling a narrative adventure with full 3D environments might charge, say, £15, and they might have to choose between recycling some content in their game and producing an eight-hour experience, or creating original assets for every scene and ending up with a four-hour experience. Most gamers aren't going to exchange £15 for four hours of play, so most developers can't put out an anthology without upsetting a lot of people and possibly bankrupting themselves.

Today, writers more frequently release individual short stories outside of anthologies. Not only is the world wide web stuffed to bursting with fanfiction, but you can also buy sixteen-page ebooks that don't have an equivalent in physical novels. This is, of course, because the internet allowed for a cheaper replication of media which meant that you could sell one story on its own without stapling it into a collection. For an author, this format may be preferable because they can provide a more constant flow of writing and let their fans pick and choose which stories they want to dive into. Whereas physical anthologies are released slowly and audiences may have to buy stories they don't want to get to the ones they do. The same principle applies to games as hundreds of more protracted interactive experiences hit Steam and itch.io every year.

So, now that the anthology is no longer necessary packaging to market-proof a piece of entertainment, is it obsolete? I don't think so. Stacking a series of stories or games back-to-back means that the audience is going to absorb them differently than if they experienced them as isolated works. Readers or players can more naturally compare how different segments of the anthology speak to the same themes in a way that's hard to if you have to search out all those pieces separately. No Code's 2017 game Stories Untold is an excellent example of how the juxtaposition of stories changes how they scan. Using the tagline "Four stories. One nightmare.", Stories Untold presents itself as a horror sci-fi anthology, which is surprising when we know that the games industry generally avoids the anthology structure. The title is made up of four chapters, and we're going to talk about them in order.

Chapter 1: The House Abandon

Psychologists tell us that part of the appeal of horror lies in being able to mentally experiment with dangerous concepts in a context where we are none the less safe from them. If you're enjoying a teen slasher flick, that's at least partly because the film suggests that you're in danger enough to get your endorphins pumping. However, it's the knowledge that the threat is fictional that keeps it from slipping over the line from fun to traumatising. The horror of The House Abandon is that of the fourth wall vanishing and an audience member being directly subjected to the depravity behind it.

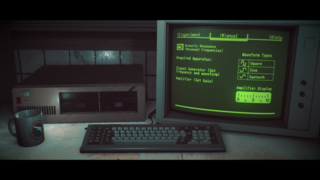

The story starts by baiting us in with emotions of 80s nostalgia rather than fear or anxiety. We sit in front of an archaic bedroom PC late at night, and on it, we play a text adventure called The House Abandon. The program starts with us in a stationary car, reading a note that cordially welcomes us back to our house. Our visit is framed as a return to a childhood home of peace and comfort: the house is quiet, the garden is well-maintained, and stuffed toys are laid out over our sister's bed. Although, given the genre, there is a lot of the PC telling us "I'm sorry, I don't understand". Then, within the text adventure, we find the same computer we're playing on in the 3D world, as well as a copy of The House Abandon. The power goes out, and the game reboots to a corrupted title screen.

On this second pass, we fall out of the warped door of our car in front of a house that is grotty and neglected. This time, our note is accusatory and condemning, and as we head through the house, the text on it changes. Both that letter and the door to the utility room are daubed in blood, and a carcass rests on the kitchen table. The eyes on the family photos are crossed through, and our sister, Jennifer's room, is boarded up. This time, as we take actions in the text adventure, the house we're sitting in in the 3D environment undergoes corresponding changes. For example, when the video game character turns on the generator behind the house, our lamp flickers; when they enter the home, we can hear someone walking around downstairs. As a future loading screen tip will remind us, sometimes we need to look beyond the screen to progress. The chapter ends when we tell the text parser that we want to open the bedroom door and the text adventure and larger game merge into one. We see a silhouette of someone over our shoulder, and the CRT reports that we are witnessing ourself sitting in front of the computer. The program displays a confession of guilt from someone to Jennifer and their parents, and makes us type the phrase "IT WAS ALL MY FAULT" before it will end.

In addition to commenting on the fear of fiction morphing into reality, The House Abandon is also about the horror of confronting the self. It's not clear until we're approaching the ending, but the footsteps and flickering lights that spooked us so much were all us, and the terror is in our awareness that we are the operator of the game, even if non-diegetically, you know you are the operator of the game. Furthermore, the chapter speaks to how horror isn't just about reacting to external stimulus but also about having us scare ourselves.

Chapter 2: The Lab Conduct

In The Lab Conduct, we don the white coat of Mr. Aition, a researcher performing invasive experiments on a biological sample of unknown origin. That sample is locked securely inside a steel safe, but we can see it through a blown-out video feed on which it looks unsettlingly like a wet heart. A nearby computer communicates a plan of action, and from it, we learn what settings we need to tune our bank of monitors, modulators, and other electronic equipment to. We x-ray and laser the muscle at the behest of the soft-spoken Dr. Alexander, looking to elicit a response from the bloody mass. When it does finally show some sign of life, it's it beating faster and faster until it explodes. Inside is a metal orb which we drill into.

Alexander then tells us to open up the box which causes the sphere and its probing torch to float right out into our face. As it turns out, the organ is a storage device that the organisation recovered from a UFO crash site. The initial experiment wasn't about checking the biological material's reaction to stimulus; it was about us forming a link to that alien biology via the orb. The tether then allows us to play back the extraterrestrial's memories of watching a researcher recover it from the wreckage and strap it down to a cold laboratory table. The orb also inflicts on us visions of a woman's face, a readout of an ECG, and the view from the driver's seat of a car. Our boss tells us that we're "doing well", and that they're aware how hard the process must be, but shows no reticence in forcing us through it. Alexander soon realises that the alien is not dead and that the psychic umbilical has brought us to identify with the creature. We feel what it feels and have shared experiences of mistreatment at the hands of the unnamed organisation. The lab has inadvertently put us in the perfect position to free the extraterrestrial, as we are both the captor and the captive. So we uncuff the alien, and as it, wreak revenge on the researchers. The doctor tells us that one day, this will haunt us.

What I admire about the writing in The Lab Conduct is how it's able to build on the concepts of the first story and explore the same set of themes as it while still providing a wholly original narrative. The House Abandon introduces us to the possibility of our inputs into a computer affecting the real world, and within that story, those effects constitute a twist, but the writer can't pull that twist again now that we're wise to it. So, what he does is put us into a scenario where we already know our manipulation of the electronics will translate into the manipulation of real-world objects: a biological experiment. At first, it appears that now that we understand we can use a computer to alter our world, we have mastery over the process of that alteration, and can safely leverage digital technologies towards whatever nefarious purpose we want. This is, of course, the game luring us into a false sense of security to set up its horror sting.

In The House Abandon, we believe that us assuming the role of player and the subject we operate on being fictional will protect us from harm, but that turns out to be a false assumption as we learn that our subject can physically disturb us. In The Lab Conduct, we think that assuming the role of researcher and operating on a subject of research guarantees us safety. After all, plenty of scientists have performed and continue to perform experiments where they create some degree of distress in the participants safe in the knowledge that they won't have to endure it themselves. Much like in The House Abandon, it's shown to be only hubris that props up this belief, and the barrier between researcher and subject very literally breaks down as the safe opens, and we psychologically combine with the subject.

In both The House Abandon and The Lab Conduct, the game also dissolves a more metaphysical barrier between the operator and the person being operated on. The House Abandon challenges our conception of the player and protagonist as distinct entities by giving us a story in which they're one and the same. We can interpret this first chapter as saying that fiction cannot be locked away in its own little box separate from real-life because it reflects reality and pushes with emotional force on real people. The Lab Conduct suggests that researcher and test subject are not as far apart as you might think by showing that they're both tools at someone else's disposal and that their roles could easily be switched. In both cases, we reach these realisations through the confrontation of the self, and in The Lab Conduct, the literally alien comes to be familiar. The idea of the extraterrestrial as disquieting invader gives way to the view that if eggheads at Roswell had been dissecting little grey men, that wouldn't just have been "creepy", that would have been xenophobic butchery.

In the first story, we attempt to detach ourselves from another person while manipulating them, and we initially fail to recognise the self, which leads to disturbing consequences down the line. The second narrative flips this concept on its head. It shows how empathising with a subject and confronting the self can lead to a mutual liberation. Where the opening tale is about coming to recognise the self as a painful and fear-inducing process, the game's sophomore story has us go through that same experience but then overcome that pain and fear to reach a place of empowerment in self-recognition. And where story number one shows how a computer program affecting the outside world could have chilling consequences for us, The Lab Conduct suggests that we can also weaponise the power of computers against people who would use them to hurt others.

Chapter 3: The Station Process

The game fizzes with symbolism as we round out episode two, but there's not nearly as much depth to be found as we embark on The Station Process. In this third chapter, we assume the role of a J. Aition, a pencil pusher at a numbers station in a remote tundra. As one of our colleagues tells us, we could do this job in our sleep. We play by decrypting signals that come in over a radio and then executing protocols from our handbook based on the result. The protocols all have cool names like "Jennifer", "Drive", "Chevron" or "Whiskey" and each has us inputting commands into a computer for some ambiguous purpose.

For its first three chapters, Stories Untold dials up the opaqueness of our tasks bit by bit. In The House Abandon, we immediately recognise our subjects and our method of interaction with them. Our subjects are a video game character and world, and our method of interaction is a text parser. In The Lab Conduct, we're familiar with our method of interaction but do not initially clock who or what our subject is. We know how x-rays, cameras, and drills work, but we're given no information about the target we're using them on. In The Station Process, we don't, at first, understand our method or subject. We're clear on the set of rules we must abide by to achieve "success", but don't know what our computer does once primed with the inputs we give it.

| Method of Interaction | Subject | |

|---|---|---|

| The House Abandon | Understood | Understood |

| The Lab Conduct | Understood | Not understood |

| The Station Process | Not understood | Not understood |

Between some sightings our coworkers make, a few computer outputs along the lines of "Launch Initiated", and a distress signal telling us "New York has fallen", a picture of world events emerges. Dangerous humanoids are taking over the planet, and with our data entry, we're initiating nuclear strikes to eradicate them. One of those humanoids appears over our cabin, and later, we find ourself unable to continue launching as a nearby electrical hub goes dark. We must steel ourselves and walk out into the raging snowstorm where we'd expect to come face-to-face with one of the monsters, but we never do. We see some crashed cars, spy some barrels with the phrase "WARD 4" on them, and get the power flowing. As we head back, our colleagues transmit strange messages to us, telling us they can't feel their legs, or that everyone is waiting for us to wake up. It's not even clear how they're talking to us if we're away from our station. At last, we open the door to our shack again, and inside is the bedroom from The House Abandon.

Like The Lab Conduct, The Station Process starts off describing how we can use the world-altering powers of computers to cause suffering, but where The Lab Conduct is about how we might do that on purpose, The Station Process is about us damaging the world through digital technologies while being oblivious to our actions. It's the abstraction inherent in these mechanisms, both actual computer systems and the gameplay system that models them, that leaves us unable to tell what the systemic interactions we perform do. Computers allow the efficient translation of straightforward plaintext instruction into a series of codes, and in a Chinese Room scenario, we don't need to understand what those codes represent to do our job, we just need to know which responses we must give to each item of data. We know what input corresponds to what output, but once we produce that output, it's lost into a void of computer networking beyond our range of vision. That lack of clarity is symbolised via the snowstorm that clouds our view of the world outside the window. While DEFCON is a game speaking to the guilt of perpetrating a nuclear apocalypse, The Station Process suggests the scary concept that a person could bring about a worldwide genocide without even knowing they're doing it. But that's all the subtext you can extract from The Station Process; the story doesn't have as much to say about its topics as The House Abandon or The Lab Conduct do about theirs.

One reason that The Station Process lacks depth in comparison to its peers is that the first two chapters give you plenty of time with the computer equipment, letting you see it morph into new and challenging shapes, but in The Station Process, you get up and leave the monitors and keyboards about two-thirds of the way in. At the point that these other stories are undergoing their second major shifts in how we perceive their technologies, The Station Process is having us stagger about in the blizzard. It's a twist that we, for the first time in the game, must get up from the computer chair, but we can see it coming from the moment we're told that whatever we do, we shouldn't leave the cabin. Trudging around a level is also something we've already done in the large majority of games which prevents it from being a mechanically fascinating twist. It's just wasn't worth the developers implementing it when you consider how far it drags us from the objects of interest in the game.

Another cause of the shallowness in this chapter is that, for structural purposes, it has to remain obscure to the end. The previous two stories immediately revealed consequences to our behaviour: in The House Abandon, they were the state changes in a text adventure game, and in The Lab Conduct, they were the provocation of a biological sample. Because these levels establish a pattern of cause-and-effect early on, they then have plenty of room to evolve our initial understanding of that cause-and-effect. The Station Process is not open about the knock-on effect of our actions until the episode is almost over, and so, has less space for exploration or reinterpretation of that effect. But we've reached the limit for how much we can analyse The Station Process without describing the next chapter because No Code designed this tale as a doorway to the next.

Chapter 4: The Last Session

At risk of being labelled a misleading narrator, I have to point out that I didn't ever say Stories Untold is an anthology. I only discussed anthologies and said that Stories Untold presents itself as one. In reality, there is a metanarrative that underlies chapters one to three and that the game unveils in chapter four. We learn that we are James Aition, a hospital patient awoken from a coma who has been participating in a series of therapy sessions with a Doctor Alexander. These sessions have him recalling events which led to him landing alone in a hospital wheelchair in "Ward 4" of the facility, the phrase printed on The Station Process's barrels. James is an avid watcher of a Twilight Zone-style television show called Stories Untold and has been attempting to bury the harrowing memories of his recent life under fantastical premises inspired by the programme. This is what the previous three chapters were and why Stories Untold's tagline is "Four stories. One nightmare": there was only a single plot despite the tetrad of narratives. However, every time James dissociates, the truth behind the fiction still eventually bleeds through.

In The Last Session, the dam breaks, and James confesses both heinous crimes and agonising trauma to his doctor. This confession comes in the form of us running back through the previous three sections, but this time, seeing the reality that underpins them rather than the fiction James tries to paper over them. Starting with The House Abandon, we learn the titular house was James's family home. One night, the Aitions threw James a going-away party there where he drank until severely impaired, tried to drive his sister home, and rammed into an oncoming car, hospitalising her. In the original House Abandon, James tried to regress into the older, more nostalgic image of his home: a place where he could still sit down in his bedroom with a spooky video game. When we play back through it in The Last Session, we can see the accident coming a mile off. Many players are going to have the natural response of wanting to keep James sober and driving at a sensible speed, but the game will not honour those actions, sometimes printing to the screen that they're "Not what you did". Here, the player attempting to enact narrative autonomy and being unable to is a metaphor for someone wishing they could change the past but finding their history already determined.

The collision fatally injures Jennifer, and afterwards, a police officer arrives at the scene, prompting us to plant a bottle of liquor on the driver of the other vehicle. It's James's paralysing inability to face what he did to his sister which is why, in the second version of The House Abandon, Jennifer's bedroom was boarded up, the house held a horrible atmosphere, and James was so disturbed by his own presence. The red X on the utility room door marked the place from which James borrowed the bottle of whiskey he placed on the other driver, the body on the kitchen table was most likely his sister's, and the blood on the letter was probably Jennifer's. "I'm sorry, I don't understand" was the standard response that the text parser in The House Abandon used to indicate an unknown command, but this is also what James's mother said upon finding out that her daughter had died from her injuries. James's family subsequently disowned him. The "real" events also explain the protagonist's confession of guilt at the end of the original House Abandon, and you may have noticed that one of the drivers in the game's credits is a James Aition.

There's a moment in the hospital where we're being wheeled towards the exit but are suddenly turned left, imprinting on us James's longing to escape from this nightmare but freedom being just out of his reach. There's also a scene where we wake up in the department's utility room, again, referencing the alcohol, and where we find a pair of keys "heavy" in our hands because they reflect the car keys, an object of guilt. James uses the keys to unlock a door in the hospital he's never entered before; symbolising him visiting that troubled part of his mind he'd feared to go to. As that one loading screen tip said, sometimes we need to look beyond the screen to progress; James needs to get away from the TV and come to terms with reality. At one point in the return journey to The House Abandon, we see the CRT in front of us break. It's symbolic of James's windshield smashing during the car crash, but also of a fourth wall break in which the depressing reality behind these fictions pierces through the ameliorating fantasy that James tries to drape over them. The original House Abandon introduced us to the idea of a regretful audience member using media to escape their shame and The Last Session trucks that camera back one more time.

In the new Lab Conduct, we learn that the "alien autopsy" was actually conducted on James and was the emergency surgery that doctors performed on him following his vehicle impact. Attempting to awaken the alien organ was a metaphor for defibrillating James's heart and drilling into the orb mirrored the trepanation that the staff used to relieve pressure from a haemorrhage in James's skull. The voice which calmly coached him through the experiment was that of his doctor. What James did with The Lab Conduct was to take this procedure in which he was a helpless victim and reorient it so that he was the person in control and the one inflicting the pain. However, he ends up back in the position of being operated on, and again, discovers that he is petrified and alien to himself.

The process of loading memories from the black box reflects his recollection in the therapy. Doctor Alexander's dialogue as we start the final session is identical to what the Alexander in The Lab Conduct said as we prepared to commune with the proxy. Many of the images we saw within the orb were then ripped straight from real-world circumstances: Jennifer's face, the driver's seat of the car, and the heart monitor. The alien sitting by their crashed ship, watching the researcher bare down on them with a flashlight was also a sci-fi reinterpretation of both the police officer finding James after his crash and the psychiatrist recording James's therapy session. The memory replay process is retribution for the pain he caused the alien, and he comes to empathise with that humanoid through his psychic link. Similarly, we can frame the real surgery as James's payback for violently killing his sister, and through being gored himself, he understands the violence he inflicted on her during the car crash. The extraterrestrial does turn on the researchers at the end of The Lab Conduct, but at best, this is a metaphor for James rejecting the help of the doctors.

Then there's The Station Process, James's fictionalised digestion of his family playing numbers games with him while he was comatose. When our colleague told us we could do this in our sleep, that wasn't a figure of speech, James really was unconscious. The codenames of the protocols in this segment all refer to triggers of his distress: "Jennifer", the "Chevron"s on the road, the "Whiskey" he had on him, etc. Notice that "Alexander" is the final code he uses in the launch puzzles. Unable to keep up this illusion, James finds voices from the hospital seeping into the hallucination and even sees the car wreckage out in the tundra. After wandering through his mental wilderness for a while, he arrives back at his own home: the springboard of his guilt. In the game's denouement, James runs through the hospital from the alien orb as it imitates the voice of his sister, chastising him for killing her and failing to take responsibility. You'll notice that the blinding lights, the camera, and the tape deck used to record James are all methods of literally seeing the true James better, either illuminating or watching him. But despite our keener perspective on who this man is and who he's hurt, at the end, our protagonist returns to the soft glow of the television. He still seeks escapism instead of internalising the reality of who he is and what he's done.

Likely due to the production constraints we discussed earlier, Stories Untold can't be an anthology; it has to recycle. However, it feels like No Code is attempting to incorporate that recycling into the plot. The studio knows that they'll have to make the player revisit scenarios and environments they've already explored, and so, they write a story that's about psychologically flashing back to the same places, and where the growth of the protagonist entails them confronting familiar scenarios. The ending reveal of an overarching reality is brave because it's essentially employing the "it was all a dream" switcheroo. Such conclusions can easily enrage your fanbase by suggesting that the events that seemed like they could alter plot and character arcs couldn't really. The resolution isn't rooted in character efforts or established elements of the world, and so, is a deus ex machina. The bet that the author is usually making with such meta-twist endings is that any loss of satisfaction created by the unforeseeable curveball is offset by the elegance and depth introduced by the new framing.

I should mention that when Stories Untold pulls this twist, it's not as simple as it invalidating all the plot that came before because it's not that the previous chapters weren't real in some way. It's just that they weren't real in the way we thought; often, their stakes were less than they led us to believe. There was no chance of us being possessed by an alien in The Lab Conduct, and we weren't bringing about armageddon in The Station Process. And the reveal of the previous chapters as part of an omni-narrative factors into Stories Untold's presentation as an anthology. Before the introduction of the metanarrative, each of the sections had its own personality and messaging, providing the game variation. However, that variation is wiped from the game when the chapters are reworked to all be a singular story.

It's that need to set up the overriding narrative which drowns out the character's voice in The Station Process. Unlike the first two stories, The Station Process can't be a complete narrative with twists and arcs that belong to it because its surprise reveal is the existence of The Last Session. It can't flesh out its protagonist because this would give away that J. Aition is really sitting in a wheelchair on a hospital ward instead of launching nukes from the epicentre of a snowstorm. Overall, the metanarrative version of Stories Untold isn't more compelling than the anthology version. But then, the game isn't about living in the most entertaining of all realities; it's about attempting to find escapism and only getting despair. If, like me, you're disappointed in Stories Untold's concluding chapter then the game has successfully gotten you into the headspace of James, someone who attempted to use fantastical media as an ejector seat from their life and instead unearthed feelings of pain and regret. We can't view chapters one to three the same way now that they've been recontextualised and he can't see his life, family, and home the same way for the same reason.

Although, even with that interpretation in mind, there's a couple of things Stories Untold falters on. Firstly, in comparison to the other chapters, The Station Process doesn't tell us about anything important happening to James. The House Abandon and The Lab Conduct are about landmark locations and events in his anguish. The former is centred on the home he can no longer feel comfortable in because it's where he prepared to kill his sister, and the latter depicts his agonising surgery and therapy. The Station Process is meant to be about James's family trying to play numbers games with him while he is vegetative, but those communications don't have relevance to James's manslaughter, hospitalisation, or abandonment which are the events that carry the meaning and emotional weight. In fact, when James's relationship with his family is now defined by them refusing to talk with him, I don't know why the game has a whole chapter about them attempting to connect with him.

The title also fails to tie the overarching narrative to the initial arcs in never fully explaining the theming of the chapters. Every time that James pulls the wool over his eyes, he does it via electronics: A retro PC, operating equipment, or a numbers station. But we never learn why he chooses that framing. Circuits and retro UIs are not pertinent to his car crash or the events that followed, and we don't know of any personal affinity that James had for technology. The fourth chapter wants us to leave with the impression that every knob we turned and odd phrase we heard from an official were not sci-fi novelties but meant something to an average human being. But making all the details mean something doesn't necessarily mean that when people stand back and look at the larger picture of your game that that picture will be pertinent to any deep personal experience or philosophical subject. In Stories Untold, theme frequently does not connect with plot.

Conclusion

The search for narrative anthology games goes on. Stories Untold is, truthfully, not one, and in what it is, it doesn't entirely hang together. However, the title is deeply fascinating to me because it repeatedly finds fresh ways to discuss the dynamics between human beings and both fiction and technology. Like DEFCON, Stories Untold looks at where computers facilitate emotional distancing so that horrific actions may be ignored or even perpetrated. But unlike DEFCON, it suggests a futility in attempting to use screens and systems to censor out other people or parts of yourself. Computers and fiction may allow us to disconnect from ourselves for a short time, but in Stories Untold, they always ultimately force us to confront how we relate to the world and people in it.

Horror stories can take our focus away from our own pain and allow us to study someone else's instead, but the monsters in horror represent real-world fears which we may have to combat. Lab equipment ostensibly allows a sterile and objective means for one person to experiment on another, but if we have the optics to get a vivid picture of another person, then we are going to recognise that they are a person, and we are the same. Stories Untold understands the real horror. It's not sensational axe murderer tales, extraterrestrials, or mysterious humanoids floating above our shed. It's contrition over hurting people close to us, it's an inability to introspect because we fear what we might find, and it's echoes of communication with loved ones we've lost. Thanks for reading.