Get Back: The Beatles: Rock Band and the Group's History

By gamer_152 5 Comments

In 2006, George Harrison's son, Dhani Harrison, found himself at a party on a tiny, sunlit Caribbean island. At that party, Harrison had a chance meeting with Van Toffler, then president of MTV. Dhani told Toffler that he'd been up long into the wee hours, the night before, playing Guitar Hero, and described his idea for a version of the game which included drums and a microphone alongside the guitar. Toffler told him his dream title was real and in development. Whichever way it played out, the MTV head honcho was impressed enough to put Harrison in contact with Alex Rigopulos, the CEO of Harmonix, and the two began to discuss the possibility of a rock rhythm game based around the music of the four boys from Liverpool. Dhani took his own initiative, introducing Rock Band to Apple Corps, The Beatles' record company. By 2008, Harmonix had a prototype of the game which they demoed for the Harrison family, Yoko Ono, Ringo Starr, and Paul McCartney. They all gave the build the green light. Creative Director on the game, Josh Randall would later describe the development as "The hardest thing I've ever done in my life".

It goes without saying that the work that Harmonix and Apple Corps collaborated on would be heralded as a masterpiece of the music game genre, but it would also represent a landmark for The Beatles' catalogue. Apples Corps was notoriously protective of the band's discography, to the extent that even well into the age of internet commerce, their music wasn't for sale on any online platform. That the company was prepared to issue the first digital releases of The Beatles' work represented a landmark for them, but they showed particular respect for the medium of games by doing it through a Rock Band entry. And that to that entry, Apple Corps would also add rare footage and photos of the group, as well as previously unreleased recordings of their studio mutterings, only increasing its historical worth.

The way that Harmonix talk about it, the success of The Beatles: Rock Band was down to a mutual respect that they and Apple Corps held for what they were creating. They viewed the project not just as another vehicle for the tunes of the 20th-century's most prominent pop act but as a piece of art celebrating that music. The developers hoped that the fans keeping The Beatles' torch lit would see the title as an appropriate veneration of them and that the group's sublime talent might enchant Rock Band players who'd not yet met them. This leaves me walking against the wind because I don't think it's easy to learn an appreciation for The Beatles ground-breaking upheaval of rock from this game.

If you're anything like me, you first heard The Beatles decades after their reign, and you probably found that a lot of their early music was in love with most of the generic rules of pop. However, it comes across that way precisely because The Beatles set many of those standards, in the first place. These songs are now half a decade old, and both because of the generation gap and because The Beatles form a horizon beyond which early pop history fades out, it takes some explaining to get an insolent 90s kid like me to understand why they were king. But as Josh Randall, said: "It's not a history lesson". Art Director Ryan Lesser told us "We could have just gone point for point for point and kind of recreated their time together, and that wasn't exactly we wanted to do. We wanted to breathe some new life into this world".

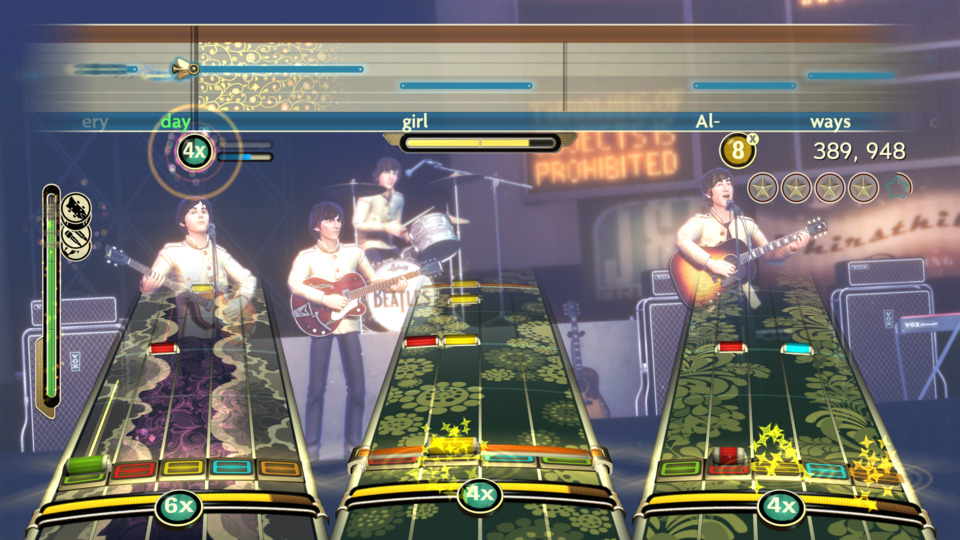

The title isn't meant to be about an educational experience with The Beatles, but a sensory one. There is not a single scene of dialogue in the story mode, nor are they animated doing anything apart from performing their songs or acting out their lyrical content. The game's fanzine cutscenes whisper the look of a time, place, and people rather than its raw chronology. For better or worse, it makes for an impersonal portrayal of the band. Critically-acclaimed homages to music acts in film, TV, books, or on stage are seldom this abstract; it's only once in a blue moon that you'll find an example of one that isn't narrative-driven. Video games have traditionally been more comfortable eschewing explicit narratives to leave only naked theme and feeling, as a lot of music does. This is how Rock Band had always played it, and Harmonix wasn't going to stop with The Beatles.

This approach means the game can leave newcomers to The Beatles mystified about their relevance to rock music, and it makes the structure of the virtual band's career feel positively mutant. There's an established trajectory for becoming rock gods: You start out torturing chipped, second-hand instruments in your garage, then you play some local gigs in cramped, stuffy venues. You graduate to something like a state or county-wide festival and go from becoming someone your friends brag about knowing to someone strangers want to know. Then you push your way up through the national and international circuit, squinting over the stage lights to throngs of adoring fans at stadiums and concert halls, eventually playing the world's largest capacity arenas like Wembley or Madison Square Garden.

Reflecting their rebellious fashion, The Beatles' career in this story mode unfurls nothing like this. The band starts off playing an underground venue, quite literally, rocking the faces off of youngsters at Liverpool's Cavern Club in 1963, but here, the game skips past the first three years of the group's history. Afterwards, instead of climbing a steep ladder to global acclaim, you're immediately catapulted to it as The Beatles play The Ed Sullivan Show in '64 and follow up with New York City's Shea Stadium in '65. Then, as quick as The Beatles took to the road, they leave it, as in 1966, you play a chapter glibly called "The Last Tour". The Beatles are the most popular music act in the world at this time; we still have half the game to go, and yet, against all logic, they're never going to play a show again.

Three out of the four remaining chapters are spent recording at Abbey Road Studios, reflecting The Beatles' in-house work from '66-'69. Cut off from the roaring crowds, consigned to an undecorated beige box for the next three years, this would seem to be a prison sentence. Instead, it begins a journey of cosmic proportions. Our first song in the studio is Yellow Submarine from the Revolver album. As its guitar moves from sustained notes to duplets, the screen begins to quiver as though the visuals are being refracted through water. Then, when it breaks into the chorus, our field of vision fills with bubbles, and we see The Beatles standing atop a coral reef, the titular submarine taking laps around them. And it continues like this: you can see star constellations paint the heavens behind them during Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds or watch light burst through the clouds as the band play on a grassy hillside in Here Comes the Sun. All the time, the quartet's music is becoming less conformist and more imaginative.

Up until this point, Rock Band had only ever shown you what it would look like for a group to perform a song. The Abbey Road sessions are Harmonix, for the first time, rendering what it feels like to listen to a song, as well as the imagery it causes to appear in the mind's eye. This also means that whatever the menus might tell you, it's not entirely appropriate to refer to the in-game stage for these three chapters as just "EMI Studio 2". The stage is also an Octopus's Garden, a bandstand in a park, or a serene meadow. The songs decide the setting, and so, the settings change when the songs do. But then, just as The Beatles' live shows came to a sudden halt with no warning, so does the band.

It's 1969, just six years after these wunderkinder started harmonising together, and most of us will know that the tracks we're hearing are ferocious commercial successes by the fact that they've echoed down the ages. So there doesn't seem to be a reason for The Beatles to go their separate ways, but they are. The venue for the final performance is curiously humble. If the world's most successful pop group broke up today, promoters would immediately spit their coffee at their newspaper and scramble to find a stage big enough for that act's swan song. However, The Beatles sunset an unparalleled career by playing a concert nowhere more prestigious than on the roof of their company building. The game puts it beautifully: "The ideas kept growing wilder: maybe they'd play aboard a ship or in the middle of the Sahara. Another idea was to perform at sunrise in a North African amphitheatre. [...] In the end they opted just to go up the stairs". It's hard to draw a line of influence from the music at the end of the Abbey Road recordings to what the band play from the dizzy heights of the Apple Corps HQ roof. The songs before were pushing the envelope, LSD trips and meditations immortalised in vinyl. These numbers from '69 and '70 are a little more middle-of-the-road, a little less offensive. And then, with no further fanfare, the game ends. The four men who did the most to revolutionise the pop music of the 20th century see their light blink out on top of a pile of bricks in Mayfair one cloudy February day.

These unexplained left turns in the story let you know that there are driving forces behind its facade that it's not talking about. Playing through the career mode is like seeing a fin sticking out above the water but not being able to see into the murky depths below. I want us to understand the history that the narrative in The Beatles: Rock Band arises from and talk about why the band honoured in this game changed the face of music forever. So, let's take a look below that fin.

For the working class, post-WWII Liverpool was not accommodating. If you were a woman, you were reliant on the income of a man, and if you were a man, you worked a back-breaking manual labour job for a pittance, if you were lucky. If you were unlucky, you were one of a generation displaced from their profession by the deindustrialisation of the area. It's against this backdrop that in 1956, John Lennon forms one of the most important bands there's ever been: The Quarrymen. The Quarrymen were typical of the material conditions in Liverpool at the time in that they were a skiffle band: a troupe that uses household and improvised items such as jugs and washboards as instruments, typically due to the poverty of the members.

Over time, the grade of instruments The Quarrymen used would improve, and they would make numerous changes to their membership, including hiring the fresh-faced youngsters Paul McCartney and George Harrison. McCartney and Lennon had a unique hurt to bond over; they both lost their mother at early ages. McCartney's to an embolism, while Lennon's was run down by a drunken police officer. Over the years, The Quarrymen tried on multiple names, including Johnny and the Moondogs, The Silver Beetles, and finally, at a point in 1960, The Beatles. There's no single change we can pinpoint that made The Quarrymen into The Beatles; instead, the original band fades into the other as its components are changed out one by one. You might not consider The Beatles of 1960 to be the true ensemble anyway. John, Paul, and George are there, but this was before the group brought on Ringo Starr as their drummer. At that time, they had Pete Best on drums and Stuart Sutcliffe as a dedicated bassist.

As "The Beatles", the band received early praise in Hamburg where they initially worked in a strip club called the Indra, playing six days a week, five hours a night. They slept in the windowless storage room of a nearby cinema and would wash in the public toilets which would sometimes overflow into their lodgings. The owner of the Indra, Bruno Koschmider, later promoted them to the Kaiserkeller, a venue where the stage was made from wooden planks slung across beer crates. They'd go on to play The Top Ten, and finally, The Star Club, all of these locations being part of Hamburg's red-light district. However, The Beatles' contract with Koschmider stated that they wouldn't frequent other venues, and Koschmider claimed that he was frustrated with the band for their troublesome antics in his place of business. He retaliated against the group by firing them and alerting the authorities to the fact that Harrison was working in the country underage, causing him to be deported. McCartney and Best got their revenge by lighting a small fire in his place of business, which then got the remaining Beatles deported. They returned to Germany, not long after, where they would play for violent mobsters and appear on bills alongside Little Richard. Closer to home, The Beatles became a favourite at their local haunt, Liverpool's The Cavern, despite rock 'n' roll having been banned from the club when they started playing there as The Quarrymen.

In July 1961, the band lost Sutcliffe as he returned to the art world from which The Beatles had first procured him, and he handed the bass to a reluctant McCartney. The following year, Sutcliffe would die of a brain haemorrhage. In November 1961, The Beatles were discovered at The Cavern by Brian Epstein. Epstein served for a short while as the band's unofficial manager, before the position was made formal in January 1962. He would go on to become possibly the most famous manager in pop history despite him having had no experience in the job pre-Beatles.

The boys needed someone taking care of the formalities, in the early 60s, no one as much as sneezed in the UK music industry without the say of the big labels. On New Year's Day, 1962, Epstein presented one of the big seven, Decca Records, with an audition from the band. Decca turned them down, and while there's no decisive agreement on the wording of their rejection, it went something along the lines of "They're not that good, and guitar music is on the way out". Their statement about the coming trends of popular music was as far off as you could be, but their low opinion of The Beatles might have been justified. When Epstein found those Liverpudlians in The Cavern, they were not the most skilled performers, relying instead on a fiery rapport with the crowd, and based on their performance for Decca, Epstein said he wouldn't have hired them either. He did, however, usher them into the halls of EMI Records. Here, George Martin would start putting their sound to vinyl, beginning his stint as the long-time producer for the band.

Epstein also got The Beatles out of leather jackets into suits and tailored their sharp early 60s look. As Lennon has discussed, there was a classist prejudice at play here. The working-class background of The Beatles was a potential liability in wider society, including the entertainment industry. The suits, garments with middle and upper-class associations, helped combat that. The band had Epstein fire Pete Best who Ringo Starr, formerly the drummer for Rory Storm and the Hurricanes, replaced. Rory Storm and the Hurricanes had previously shared the Kaiserkeller, that beer crate club, with The Beatles. Fans were incensed by Ringo's hiring, enough for them to hold protests outside of Best's house and for one to punch George Harrison in the face.

For the longest time, The Beatles's clean-cut TV appearances and innocent lyrics made me think they were coming from somewhere more naive than many later rock bands, but their early history is proof that they knew what suffering was and were no strangers to the seedier side of entertainment. Their on-camera presentation was just that: presentation. We also can't bring too many of our modern pre-conceptions to The Beatles' lives when it meant something very different to become a popular music act in the early 60s than it does today. The Beatles were both a pop and rock quartet, but the electric guitar and the use of the term "pop" to describe a distinct style were relatively recent developments. And rock was a genre still evolving out of the primordial soup of rock 'n' roll. Rock 'n' roll could chart, but it was a sound developed by African-Americans, built on the back of earlier black music such as rhythm & blues and jazz. There were widely-enjoyed white rockers like Ritchie Valens and Buddy Holly, but they were adapting music from black people, and many other stars of the format were African-American musicians such as Chuck Berry, Billy Preston, and Sister Rosetta Tharpe. Every industry gave the cold shoulder to anyone non-white, so intrinsically, there was weighting against many forms of rock 'n' roll.

Bands were also commonly backing acts for charismatic faces rather than cohesive units where everyone took the limelight. Some of the most famous examples being Cliff Richard & the Shadows, Bill Hayley & His Comets, Gerry & the Pacemakers, and Rory Storm & the Hurricanes. Additionally, the UK mainstream music scene was largely considered a grainy photocopy of the U.S.'s which had given rise to such hit artists as Elvis Presley, Frank Sinatra, The Everly Brothers, and Johnny Cash. The UK simply didn't have equivalents of these figures with anywhere near the same panache, and some acts were even purposeful store brand rip-offs of trendy American musicians. Across the board, mainstream music acts played whatever the record company told them to. Lucrative business came through a synergy of producers knowing what would sell and the showpeople realising that product. And these sultans of the stage were only too polite to interviewers.

If you need some idea why The Beatles are seen as revolutionary, start with this: They broke every pattern I just mentioned. The band covered then-contemporary black music from artists such as The Shirelles, The Miracles, and Little Richard, although their favourite for own-versions was Chuck Berry. Billy Preston also contributed keyboard to the band on tracks from the Abbey Road and Let It Be albums. He did the same for their final concert, but Harmonix omitted his appearance from the game. African-American rock 'n' roll also became an influence on the group's original compositions, and in playing these songs, the band pushed rock further into the public eye. The Beatles are sometimes credited with inventing or saving rock 'n' roll which is somewhat over the top, but they were vital for establishing rock as a genre.

They also didn't break themselves down into this frontman/backing band dichotomy. They weren't John Lennon and the Beatles, they were just The Beatles, and the same people singing were the ones playing the instruments. The same people playing the instruments were then also the ones penning the songs. Young people in 60s Britain had a little more disposable income than generations previous, and that spending could be the rocket thruster which could launch one of these bands to the stars. However, when most of the pop scene involved studio representatives trying to formulate commercially successful songs, they often lacked heart. The Beatles were a group of young people who knew what other young people wanted to hear and were making that music from an authentic place.

They didn't rise to fame coddled in cotton wool or designed by executives; they were a self-made band from as normal a background as you could find. It only increased their relatability that when they spoke with interviewers, they didn't talk to them like they had been called up to see the school headmaster; they fired off witty jokes and talked amongst themselves in a friendly manner. The band also appealed to many sonic tastes simultaneously by writing music which was influenced by a whole gamut of styles from blues to ballads. Plus, while other great acts had their music flow from the mind of a single astounding writer, The Beatles had three extraordinary composers: McCartney, Lennon, and Harrison. McCartney would later describe how a collaborative approach to composition would make them more than the sum of their parts.

Even once I understood the splash they made in pop music, I did have a lot of trouble seeing why people in the '60s were descending into red-faced outrage at the group. How could their polite bows and innocent refrains like "I wanna hold your hand" have convinced people that they were corrupting the youth in the same way they'd later accuse renegades like The Sex Pistols of doing? It makes more sense once you realise The Beatles were a little less reverent to the press and had slightly shaggier hair than their contemporaries. A lot of people also saw the screaming girls, an image which The Beatles: Rock Band takes every opportunity to emphasise, as vulgar and inappropriate. This was pre-sexual revolution, and Britain was still prudish to the point of self-parody. A lot of parents bristled at the thought of young women forcefully expressing their enthusiasm for a group of boys in public.

These possessed female fans became the poster image of "Beatlemania", a love affair with the band that swept the length of the UK. It's important to remember that music is not just an industry, but a hand that pushes on the whole culture of a society. In the America and Europe of the 1960s, The Beatles were promoting a culture of empowerment and joy amongst young people. Here are McCartney's words:

"I think that, particularly in the old days, the spirit of The Beatles seemed to suggest something very hopeful and youthful".

In 1963, the band released She Loves You, which is rarely thought of as a classic now; it appears neither within The Beatles: Rock Band's pack-in tracks, nor in any of the DLC. But when it came out, it broke the record for longest run on the UK's singles charts and would become their best-selling record, going on to rake in 1.9 million sales total. This brings us to roughly where the Rock Band game starts, and you can see much history Harmonix leaves on the cutting room floor. But this is a prime place to kick the story off: Americans were now clamouring for a British pop act instead of it being the other way around. In 1964, The Beatles shattered the record for most simultaneous top ten singles on the Billboard 100 chart. America's ravenous appetite for The Beatles is what led to the Ed Sullivan performance and blowout Shea Stadium concert that we see in the game. This began the period of U.S. music history known as The British Invasion. The Beatles had kicked down the door of the U.S. industry and in rushed The Rolling Stones, The Animals, and a menagerie of others. America was now taking the UK seriously as a source of rock music as they never had before, and it's an attitude that would last all the way up to the present day.

As for The Beatles' decision to put the kibosh on touring, the causes range from the technological to the meteorological. The band were getting bored, and even long before their last concert in 1966, they were miserable on the road. While a Beatles live show might last only a hasty fifteen to thirty minutes, in their short history, they had played over 1,400 of them. You can see their weariness register in the title of their 1964 album Beatles for Sale, as well as the cover which has the usually chipper four looking uncharacteristically stoic. Towards the end of the live shows, the audiences also didn't get to hear the four bringing their A-game. Being the most popular band there'd been, ever-vaster stadiums were required to provide enough seating for all The Beatles' followers. However, as the locations got bigger, their sound had to be projected further to be heard by everyone. That's not something that the amplifiers of the 1960s were up to, especially not with all those screaming girls in the stands. As melodic as the Shea Stadium performance might sound in the game, in the real Shea, no one could hear it. And the band competing against that racket had dulled their musical faculties. Here's John:

"There were times your voice was so bad (through losing your voice) you virtually wouldn't be singing at all, and nobody would notice because there'd be so much noise going on".

And Ringo:

"Nobody was listening at the shows. That was OK at the beginning, but it got that we were playing really bad, and the reason I joined The Beatles was because they were the best band in Liverpool. [...] My plan was to keep playing great music. But it was obvious to us that the touring had to end soon, because it wasn't working any more".

America was also a country with a lot of locales prone to chaotic weather, and the 1960s was a time of great political unrest for the nation, placing the band smack dab in the middle of riots and hurricanes. In '66 Lennon also made his controversial comment that The Beatles were bigger than Jesus, meaning that their U.S. tour that year left them inundated by protests from the KKK and violent threats. If you can believe it, their stay in the Philippines was even scarier. It included armed soldiers separating them from their staff at the airport, their promoter being taken by police in the night for a three-hour interrogation, and monarchist thugs beating Harrison, Starr, Epstein, and their chauffeur. So, the band's 1966 tour of Germany, Japan, and the Philipines would be their last.

And there was one more factor: going ahead, new modes of production would make it more difficult to ever remove The Beatles' music from the studios where they recorded. The conventional conception of production was that voices and instruments made the music, and tape machines and mixing decks were just there to capture it. But on The Beatles' 1966 album, Revolver, they imagined the studio as its own instrument which also brought producer George Martin into the fold as a musical collaborator. We take it for granted now that the way someone produces tracks is going to have a formative effect on the songs themselves. We live in an age where many rap and electronica producers are effectively the creators of the tunes with their name on them, but that wasn't how things were in the 60s.

Out of Revolver came the popularisation of backmasking: the technique of reversing sound on a record, and ADT: Automatic Double-Tracking. It was common for vocalists to record their lines twice and for the first recording to be manually layered over the second to give a more "filled out" sound. Lennon, tired of having to repeat his vocals, requested that the EMI engineers invent ADT, allowing him to perform only one take and the technology to overlay it with itself. Music production has never looked back. The Beatles couldn't play these songs live because at a live venue you wouldn't be able to overlap your singing and instrumentation many times over or be able to play your music backwards or pull off many other auditory tricks that you can in a studio.

If I can gush about one Beatles song from the Abbey Road days, it has to be Tomorrow Never Knows, a track on which the new production approaches come through loud and clear. It makes extensive use of tape loops, most consistently in the compressed drums that repeat underneath the rest of the song for its full length. It's uncannily reminiscent of the drum sampling in modern hip-hop and electronic music. There are also echoing atmospherics introduced by the sitar and tambura, and needless to say, hearing Indian or Eastern-European stringed instruments would have been outside of the comfort zone of UK pop listeners at the time. The lyrics open with a line from Timothy Leary's influential book The Psychadelic Experience and generally reflect psychedelic imagery and eastern metaphysical concepts. This was pioneering as even the term "psychedelic" wasn't yet part of the popular public lexicon. Either side of the core song, we get these flashes of instrumentals and vocals looped, sped up, or reversed, like cars passing us on a highway. Every time I listen to this track, I'm flabbergasted that it was written and recorded in 1966; without knowing, I would have guessed it was from decades later. It's a far cry from palatable ditties like Paperback Writer.

The version of Tomorrow Never Knows in The Beatles: Rock Band is an immaculate example of the game's power to intermingle its graphics and its music, but is also the one example of the game using a reworking as opposed to an original or slightly altered version of a track. The game pinches a Tomorrow Never Knows/Within You Without You mashup from the 2006 Beatles remix album, Love. Within You Without You originally appeared on the Sgt. Pepper's album with Harrison adapting it from a thirty-minute piece by sitar sensation Ravi Shankar. For Revolver, The Beatles performed it together with The Indian Music Circle even if they're nowhere to be seen in the game.

The Rock Band level for Tomorrow Never Knows/Within You Without You opens with Lennon in black and white, sounding out that famous mantra: "Turn off your mind, relax, and float downstream". He fades into colour, and as he continues to sing, the studio fills with little pink and purple orbs. Then Ringo's rhythmic drumline kicks in and the walls fall away into a void of light. Neon mandalas become the band's halos and the track phases into Within You Without You. The two songs are linked through the Tomorrow Never Knows drum loop sustaining through the Within You Without You section, and if you are playing the guitar, you get an entirely unique experience in the Rock Band series. Not only do we play a dilruba, another Indian stringed instrument, through the guitar controller, but as George's vocal melody follows the tones of the dilruba, you get the surreal illusion of being able to control Harrison's voice through the peripheral. This is how much Harmonix cared about the detailing in The Beatles: Rock Band.

The use of the Tomorrow Never Knows/Within You Without You mix backed by such transcendent imagery also lets the game more broadly represent The Beatles' forays into Indian classical music and their promotion of worldviews derived from eastern religion. That last point is particularly culturally freighted. The evolving hippie movement, The Beatles' philosophical readings, and later, the band's sojourn to see Indian mystic Maharishi Mahesh Yogi all inspired them. In turn, the group contributed to the western popularity of anti-materialism, eastern spiritual teachings, and psychedelic art styles. But it would be their next album that would become the most esteemed of the century.

In 1967, The Beatles unleashed Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band, an album which cast the group as members of a fictional technicolour marching band. Pepper's is sometimes tagged as the original concept album, but that's a questionable assertion. There are earlier candidates for the title, and more damning, Lennon rejects the notion that Sgt. Pepper's is a concept album at all. He notes that the title track, the introduction to A Little Help from My Friends, and the reprise at the end of the album are all canonically sung by the colourful band, but that the other songs on the record are unconnected to this theme and could have appeared on any Beatles release.

However, that's not to say that the work's format didn't affect its composition. McCartney has said that stepping into someone else's shoes for the recording process allowed the band an inventiveness they otherwise wouldn't have had. They didn't have to write for The Beatles anymore; their songs came from new personas entirely. And even if it was driven by faulty perceptions, the reception of Sgt. Pepper's as a holistic work implanted a respect for the concept album in the public culture. It also drove a new regard for the album as a form. When The Beatles started up, there were pop albums, and albums were well-respected in other genres, but in pop, the album had always played second fiddle to the single. The single, being cheaper and easier to consume than the album, sold more, and pop music was all about quick consumption. With Sgt. Pepper's, The Beatles had recorded pop that the masses wanted to consume in album form, and pop albums were taken more seriously as a result.

This release also helped remove the perceived barriers between pop songs and more "refined" music, as well as between pop culture and high art, in general. The album's cover represents this; it's a class photo of combined influences for Sgt. Pepper's that range from well-known entertainers like Marilyn Monroe and Oliver Hardy to members of the intelligentsia like H.G. Wells and Oscar Wilde. In the sound, the high art vibe makes itself known through orchestral flourishes in tracks like Sgt. Pepper's and A Day in the Life. The Beatles used a 40-piece orchestra of musicians selected from the London and Royal Philharmonic for this purpose. You'll also hear Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds on the tracklist, perhaps the most beloved piece of surrealist music ever written. With its initials famously spelling out LSD, this track, The Beatles' other more left-field songs, and their use of recreational drugs in the creative process, encouraged the liberal attitude to psychoactive drugs that arose in the late 60s. The album released just before the famed Summer of Love, the zenith of western hippieism.

For those of us that weren't around when these songs originally seeped into the airwaves, I don't think there's a way for us to feel what it must have been like, hearing them for the first time. Imagine a middle of the road, hyper-accessible boy band suddenly releasing songs about zen ego death and Daliesque dream sequences, and telling you they're part of a non-existent marching troupe. They're going from innocently strumming out guitar songs about train journies to playing guitars backwards and riffing on Indian music. The closest comparison I could make for the modern day is that this is like if Ed Sheeran or some of the One Direction kids started dressing up in walrus masks and singing about yellow matter custard dripping from a dead dog's eye. But even that doesn't get across how it would have been received because it's now somewhat normalised for a popular act to get weird, in part, because of the legacy of The Beatles. In the 1960s, it was all new, and given how mind-blowing that must have been, you can see why people felt an inherent link between the experience of listening to a song like Tomorrow Never Knows and taking acid. Although, while Sgt. Pepper's is almost universally praised now, at the time, this surreal turn alienated some diehard fans.

The Beatles continued this pattern of the psychedelic and experimental on subsequent albums through songs like Strawberry Fields Forever, Octopus's Garden, and Revolution No. 9. Films like Magical Mystery Tour and Hard Day's Night which featured The Beatles in scripted adventures alongside their music were critical precursors to the music video, and many, if not most music historians, identify Helter Skelter as the first metal track. And then we get up to that Apple Corps rooftop. The public had incorrectly suspected that The Beatles were on the verge of dissolving, even when they were concocting some of their most ground-breaking work. This time, however, the four really were approaching the end of the tunnel. It's true that this final concert took place in 1969 and that The Beatles didn't announce their official breakup until 1970. However, that announcement was a formality for a band who hadn't been working together for months. They did put out an album in 1970, Let It Be, but they'd recorded it before their '69 album, Abbey Road.

The in-game performance is mostly composed of tracks from Let It Be, which, after the fever dream of the Beatles' albums from '66-69, might sound like a surprising return to a singer-songwriter past. This was deliberate; feeling that the studio experimentation and far-out styles had taken over the music, The Beatles and many of their peers aimed to strip back their songs for a more down-to-earth character. In the game, this is wonderfully embodied through us returning to a real, public venue with no flashy effects or dreamscapes swirling around the men. It's just them staring out over the London which they have forever changed.

Just as there was no one reason the band ended their tours, there's no one explanation for why they disbanded. When it came to composition, the members always had different interests, but those poles were repelling more strongly than ever. McCartney had traditionally used his songs to spin yarns about other people: Eleanor Rigbys and Penny Lanes, and liked using music to cheer people up, such as on Hey Jude and Getting Better. He wished to stay in this groove. Lennon more often used his songs in an autobiographical capacity and was more comfortable in the neutral or downbeat, e.g. on Sexy Sadie or Nowhere Man. His art and mindset were also getting increasingly avant-garde (e.g. Revolution 9), and political (e.g. His later solo work such as Imagine or Working Class Hero). There are examples of each of these men wandering into every category of song I mention here, and it was normal for them to write together, but the aforementioned patterns are correct on average.

Being a Beatle was also becoming an increasingly stressful profession. The death of Epstein through a drug overdose in '67 was cutting for all involved, and McCartney alienated his bandmates by warning them against exorbitant spending on Apples' dime. To him, this was attempting to plug a leak in their sinking record company; to them, he had an excessive focus on wealth. The group had set up the label in 1968 to publish their records and joined solely as musicians, but they were now also finding themselves in the seats of businessmen. And that business was getting contentious as a disagreement broke out over who should manage The Beatles. The Beatles, or at least, The Quarrymen, were formed by John Lennon, but he felt that it was increasingly McCartney's band. Sgt. Pepper's had, primarily, been Paul's pet project.

Now, Paul was arguing for new managers for The Beatles that would appear to hand him unilateral control of the group. To resolve their negative cashflow, McCartney wished to bring on board attorneys Lee and John Eastman who were the father and brother, respectively, of Linda Eastman, his partner. But before you judge Paul too harshly, John, George, and Ringo's pick for manager was music rep Allen Klein whose company had previously failed to file tax returns and was again under investigation by the IRS. Inspectors would eventually bust Klein for tax evasion in 1977. Then there was the encroachment of Yoko Ono, John's future wife, into The Beatles' inner sanctum. A boundary-pushing artist, Lennon brought Ono into The Beatles' sessions without the consent of his other band members and her creative suggestions were frequently unwelcome. Eventually, a bed was installed in Abbey Road so that Ono could lay on it and make comments about the band's concepts and performance.

New tapes found by music historian Mark Lewisohn, and first-hand testimony[13] by writer Hunter Davies suggest that The Beatles' last recording sessions were more convivial than we've traditionally perceived them, but for all the reasons above and more, The Beatles went their separate ways. The grand finale of a Rock Band game is where it will deploy its Green Grass and High Tides or its Free Bird, but The Beatles don't have any stadium-shaking epics that could be used to cap off the career mode. Instead, like The Beatles, the game just fizzles out.

There is one more loose end we haven't tied up here, and it's how these albums became entertainment software. See, a Rock Band song requires a track for every playable instrument because, if a player misses notes, the game must be able to have that instrument cease playing while the rest continue to sound. Additionally, if a player activates overdrive, the system must be able to apply effects to the instrument they're playing on, and only that instrument. This is a problem because the '60s music production setups The Beatles were using didn't capture every instrument on its own track. The early recordings weren't even in stereo, so how were Harmonix going to split out the sound for each player? There were people who'd encountered this problem before. Remember that 2006 remix album I mentioned? George Martin, and his son, Giles, produced it. They mixed the compilation as the soundtrack for the Cirque du Soleil performance, Love, and to do it, they had to work out how to separate out the tracks of many of these songs. The answer lay in software better known for its applications by the police.

Say you're a forensics expert and you have an audio file which you suspect contains incriminating speech, but background noise in it makes that talking inaudible. Else, imagine that you wanted to isolate out the sound of a gun in a crowded room to help identify its model. Audio forensics programs enable you to filter that speech or that gunshot out. If you applied this tech to a Beatles song, maybe you could isolate the drums or the lead guitar, or any other instrument. It took Giles Martin and other engineers at Abbey Road many months to extract the stems for each song, but they did it using these tools. The concept art from Love also became the concept art for many of the dreamscapes in The Beatles: Rock Band. Although, Apples Corps only permitted Harmonix to work with inferior quality versions of all recordings until near the end of development, fearing that digital versions of The Beatles' music could leak.

Harmonix frequently shared their work in progress with the record label and the people who were closest to The Beatles, allowing them to weed out any inaccuracies. Project Lead Josh Randall describes an occasion on which Yoko Ono visited Harmonix and gave some frank feedback on their failure to reanimate Lennon. Her blunt criticism was a blow to them, but her directness allowed the developers to understand the issues clearly and remedy them. On September 9th, 2009, the public played The Beatles: Rock Band for the first time. While its sales were a shadow of Rock Band 2's, it still shifted upwards of 2 million units, more than any Beatles record.

From where I'm sitting, the game admits more than it means to about the changing quality of The Beatles' music over time. Chalk it up to when I was born, but the twangy pop of the early Beatles is, on the whole, too safe and shallow for me, even if I know that the men behind it were anything but. Where my ears prick up is when they start modernising their production and dabbling in the surreal. It's songs like I Am The Walrus and Come Together that give me shivers. I see a Beatles: Rock Band that's in agreement. The first four chapters of the game are fine, but the art isn't exactly bending over backwards to show you how special the band is. It's sepia-tinted shots of four boys in suits on a stage. What everyone remembers from the game are those enchanting dreamscapes during the Abbey Road sessions. The graphics explode with a vividness and creativity that matches the band's songs from roughly '66 onwards.

None the less, I appreciate all of the game for introducing something old to new people. Here, we've looked at a lot of facts and context for the career of The Beatles that The Beatles: Rock Band doesn't include itself. Based on that, one way to look at the game would be that it is deficient of details about who John, Paul, George, and Ringo were. But I don't think of it that way. When making media about artists, you can approach it like a Lennon, or you can approach it like a McCartney. You can use your platform to be attentively biographical and talk about the sorrowful moments as much as the joyous ones. Or, you can try to tell a story that cheers people up and omits life's drug overdoses and overflowing bathrooms. I don't think either answer is the right one, but it is clear that the Rock Band series lends itself to adapting the heart of the music as opposed to the spirit of the people who made it, and The Beatles: Rock Band follows that tradition. It could be more didactic, but by using minimal educational content and zeroing in on the tunes, it remains accessible for those who are solely there for the songs and raises just enough questions to pique the interest of anyone who might want to go on to a deeper dive into the band.

As for The Beatles themselves, they weren't just an influential band; they were a cultural whirlwind. They changed the music industry, music production, attitudes towards sex and drugs, the popularity of rock, the band format, consciousness of eastern philosophy, and the reputation of pop culture media. So, whether or not you're a self-professed fan, if you've loved pop and rock made in the last fifty years, or even if you've just been a part of western culture in that time period, you've taken a bit of The Beatles and held it close. Thanks for reading.

Sources

- Video Games: Will The Beatles Rock MTV? by Tom Lowry (August 06, 2009), Bloomberg.

- The Beatles Make the Leap to Rock Band by Jeff Howe (August 12, 2009), Wired.

- How the Beatles Changed the World (2017). Directed by T. O'Dell. Vision Films, Symettrica Entertainment.

- A Day In The Life: Creating The Beatles: Rock Band by Ryan Lesser, Dare Matheson and, Josh Randall (March, 2010), GDC Vault.

- The Harmonix Interview: Josh Randall by Harmonix Music Systems (December 15, 2011), YouTube.

- The Beatles Anthology (1995). Directed by Geoff Wonfor and Bob Smeaton. Apple Corps, Capital Records, Granada Television.

- The Beatles (2000). The Beatles Anthology. Cassell & Co.

- Forget Liverpool. Hamburg, Germany, made the Beatles into the band they became by Dean R. Owen (May 12, 2019), Los Angeles Times.

- How Hamburg changed the Beatles by The Local (August 16, 2010), The Local.

- Mark Lewisohn (October 10, 2013). The Beatles - All These Years: Volume One: Tune In. Hachette UK.

- The Beatles: Rock Band Unlockable Facts by Harmonix Music Systems and Apple Corps (2009), The Beatles: Rock Band.

- Why the Beatles Broke Up by Mikal Gilmore (September 3, 2009), Rolling Stone.

- Something in the way they grooved by Hunter Davies (October, 2019), The Oldie.

All other sources are linked at relevant points in the article.