Into the Wild Blue Yonder: Sonic Generations and the Sonic Series

By gamer_152 0 Comments

Debates about the quality of the Sonic series always follow a script: Someone makes the observation that the 2D Sonic games were fun, but the 3D ones are some combination of boring and obnoxious. Responses then typically come in the form of a large crowd agreeing, some people saying that the early 3D Sonics were decent, and some others saying that Sonic was never fun. There is also a community out there who are passionately in love with modern Sonic, but they're not that well-represented in general gaming discussion spaces. Most of us agree that the games after Sonic Adventure 2 are too childish and janky to be worth our time, but the consensus on that issue can sometimes lure us into thinking that there's more agreement on the overall series than there is. This degree of division over the games is one that you can see Sega tying itself in knots to try and reconcile. Even if you put aside the relatively small number of Sonic players who never enjoyed the series, you've got an audience who loves 2D platforming and hates the gimmicks and chirpy anthropomorphs of the current 3D Sonic. You've then got an audience of bleeding-heart modern Sonic fans who want every new game to be following up on the cinematic and mechanical qualities of Sonic Adventure, and it's derivatives. Finally, you've got a lot of the potential audience somewhere between the two poles.

Deep down, the cause of this division is that Sonic is and always was a novelty. By that, I don't mean that Sonic was created to be a shallow toy; I mean that he and his games were always designed to be novel. Mario was a throwback to retro Disney figures and other characters from the early-mid 20th century. That the characters Nintendo based Mario on lingered in the public consciousness for decades suggested that they had a timelessness to them that would also keep Nintendo's mascot from weathering over the years. So, Mario feels just as classic in this day and age as he did in the 1980s. But Sega designed its spiky blue rodent during the 90s as an up-to-the-second alternative to Nintendo's platformer protagonist. Because Sonic was invented specifically for the early 1990s, he's always going to feel stuck there, and yet because being cool and cutting edge is part of his character, Sega is always fruitlessly trying to drag him away from that point of origin. This is as true technologically as in the character of Sonic.

When Mario transitioned into 3D, Nintendo's nostalgic outlook had them developing the new Mario games to stay true to the roots of the series instead of trying to capitalise on every new feature that the latest technology allowed. The electronic limitations of the Nintendo 64 also helped keep it humble. Mario 64 begins with a short voice-acted speech, the environments and movement are 3D, and Mario has a few new jumps, items, and enemies to frolic about with, but the game is more of a Mario with a Z-axis than a new species of game featuring the same character. But Sega was concerned with making Sonic as modern as possible and using him to sell the Dreamcast on the point of raw technological prowess. That's a big part of why Sonic is so fast and so modernised in the first place: he's meant to represent that his console, in comparison to the competition, is fully up to date and has formidable processing speed. So when it came to turning Sonic 3D, Sega took advantage of all the latest developments in video game tech to bring us a more filmic mascot platformer with plenty of cutscenes, new forms of play, a wide cast of voiced characters, and a detailed open-world city, at least, by the standards of 1998. After all, "Sega does what Nintendon't". While Mario has maintained minimal speech and emotional expression, an attribute that works for kids and adults alike, Sega, in flaunting its technological tailfeathers, pinned Sonic and friends down to a certain style of speech and actions that aren't going to appeal to everyone. Mario's mechanics also turned out to be far more adaptable to 3D play.

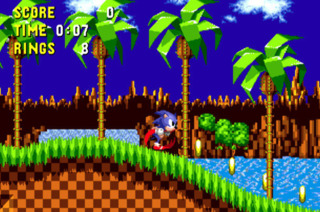

I want to dispel a popular myth: Sonic was never just holding right and watching the game play itself. That may be the image of Sonic that burned itself into your head because, for many, the unbridled sprints through loops and over bottomless pits were the most iconic events in the games, but even the first act of Green Hill Zone in Sonic 1 was more textured than that. In all 2D Sonic stages, you need to slow down and take your time if you want the maximum rings and power-ups, and by as soon as the second zone, having one foot on the brakes becomes mandatory. Levels reverse direction, try to bait you into spikes and robots, and force you to stand and wait while platforms float into place, all of which means you have to slow down now and then. This is why you often hear people say that speed is your reward for completing the more leisurely-paced sections instead of just saying "Sonic is about speed".

Because the games house so many level segments with more relaxed pacing, whether you enjoy Sonic has a lot to do with whether you find its more deliberate platforming fun. It's also influenced by how you react to the levels' stomach-lurching shifts between wind-in-your-hair rollercoaster moments and measured precision movement. Even if you connected with both in the 2D games, the series' 3D makeover amplified the issues of both. Sonic's propensity to dash across the screen at a moment's notice and his uncomfortably floaty jump are aspects you can just about control in 2D, but trying to accommodate them with an extra axis of movement involved often makes Sonic feel slippery and unwieldy.

For this reason, 3D Sonic often squeezes potentially spacious environments down to linear corridors because having the levels be wide open and movement be omnidirectional makes it awkward to navigate at speed. It's also probably why few of the games after Sonic Adventure 2 had explorable hub worlds or let you turn Sonic on a dime. It's as though Sonic wants to be a 3D experience because that's what's been in since the late 90s, but it keeps cutting back on 3D gameplay elements because it's aware of the unfortunate hindrance they are on the early 90s high-speed stylings of the series. We then have to contend with the fact that even for what they were, these 3D games were often under-developed with physics and level geometry falling out from under you when you needed them most. I wonder if this is because, knowing that Sonic was no longer taken seriously by most AAA fans, Sega began pushing Sonic games out of the door as cheaply as possible, hoping to hook the people who'd buy it for the name and characters alone.

The publisher habitually threw back to the genesis of the franchise to reclaim the alienated early Sonic fanbase. You saw this with homages like Sonic the Hedgehog 4: Episode I and II, Sonic Mania, Sonic Advance 1-3, Sonic Rush, and Sonic Rush Adventure. Sega also originally conceived of Sonic the Hedgehog (2006) as a tip of the hat to old school Sonic, but not only did the studio frequently fail to hit the spot with these retro revival projects; its dependency on them was its own red flag. The company continually gnawing at the leash of 3D Sonic to escape back to its halcyon days suggested that, on some level, it knew Sonic's best years were long behind him, and it was the sighing and groaning over titles like Sonic 4 that rekindled the debate over whether Sonic was ever fun. What's contemporary for one generation is the subject of nostalgia for the next, and while we reminisce over the good old days, we also develop past them. It's for these reasons that Sonic is stuck at an intersection. It's a series that was designed to be up to the minute but is grounded in dated cultural and design concepts, and so, can't help taking longing glances back over its shoulder, aware of the other Sonic it can never square itself with.

Sega has never acknowledged the gulf between the eras of Sonic games and the diverse expectations of its fans as directly as it did in Sonic Generations. Released in 2011, on the 20th anniversary of the franchise, Generations takes place across nine worlds, each representing one of the mainline Sonic games from 1991's Sonic the Hedgehog up to 2010's Sonic Colors. Each world has two acts: one played entirely in classic 2D and one that flips between 2D and 3D action. The former stages are played as the rounder, more child-like Sonic of yore, while we enter the latter in the body of modern Sonic, complete with his cocky grin and Goku haircut. The level select screen is also a separate micro-stage which enshrines each Sonic game as a setpiece. Those setpieces start off eggshell white, but as 2D and 3D Sonic complete the stages related to them, vivid hues return to their faces. The implication is that it's only with the Sonic of the past and the Sonic of the present that the full magic of the series comes alive. There's a good chance you disagree.

Generations' experiment in reuniting Sonic's two major audiences is one that would never be repeated and was arguably doomed to fail. But let's not be too cynical; the game was a rare response to many of the common criticisms of the series. Veteran Sonic fans hated Sonic's plucky, technicolour sidekicks, so Generations trots them out for the opening and closing cutscenes but otherwise pushes them into the background. Knowing that many spurned ex-fans felt that Sonic should have stuck to 2D, Sega gives you that alternate history version of titles like Sonic Heroes and Sonic Unleashed where you can play a portion of them in side-scroll view. You can also revisit early 3D Sonic with the more obedient camera and directional controls of later 3D games. The phrase "Green Hill Zone is the best part of every Sonic" had been echoing off the walls of the internet for a long time, so Generations aims to find the Green Hill Zone of every Sonic release and have that be the only bit you play. Its 3D interpretation of the first Sonic 1 world and its revamp of Sonic Adventure 2's City Escape are two of the best Sonic levels ever produced.

However, this format is fertiliser for a fresh crop of issues. It might offer a taster of every variation of Sonic you could want, but when stages whiz by at lightning speed, the kind of Sonic that you're showing up for might only be a sliver of the experience as a whole. A lot of the development time and resources for Sonic Generations were probably consumed producing assets for nine different Sonic games at once which likely meant that the dev team couldn't spend as much time building levels, which I'd bet is why there are only two stages per world. This also means that Generations risks being a couple of afternoons of play sold at full AAA price. The designers can't eliminate these problems, but they do make some decisions which mitigate them. In addition to the two main acts, each world has five 2D challenge acts, and five 3D challenge acts. In them, you run back through a portion of the level with a new goal, ability, or hazard added. These bonus sections have you collecting a target number of rings, strong-arming your way through extra enemies, racing the computer, and much more.

Instead of presenting stages that have one or two routes through them but that the player will devour in a few minutes, Generations uses surprisingly lengthy and layered environments because it wants you to keep passing through the game's revolving door and dashing back into those levels. In a lighter version of the level design philosophy that Hitman (2016) would use five years later, Sega offers few stages with more play as opposed to more stages with little play. Sonic feels at its smoothest when you can achieve near-uninterrupted runs through its levels, but you can't do that without some substantial knowledge of their layout and hazards. These challenges let you learn the zones and re-experience your favourites without the platforming becoming stale and while letting you continue to make marked progress.

Generations even demonstrates that 3D Sonic brought in a mechanic that would have been a godsend to have back in the retro days. Something that I've never enjoyed in the side-on Sonic games was squashing enemies. In Mario, you get this quick hop on and off of foes, but Sonic wants you to be able to cover long distances with its jump which is why that jump is so floaty and feels ill-suited for landing on anything directly in front of you. Trying to hit targets with that leap would have been downright impossible in three dimensions, and so, from Sonic Adventure onwards, the games included a homing attack. It does wonders for the flow of these experiences; you spend less time having to slow down and participate in the boring precision platforming. You can, instead, speed up to a group of enemies, homing attack between all of them, touch down, and keep on running. In Generations, not only can you use this move in the 3D sections, but when those 3D levels compress back down to 2D, they keep the homing attack in play. It allows for more fluidity than the 2D Sonic games ever had.

Unfortunately, even Generations' positives draw attention to its negatives and call back to the splits in the fanbase. Some players are going to want to talk to Amy and Silver and all those characters and not just see them pose against the scenery like theme park mascots. And as cringeworthy as modern Sonic's chums can be, it's also hard not to feel that the developers miss a trick by having the original Sonic characters meet their current versions and then doing nothing with it. There's a lot of possibility in there for Sega to playfully explore how those characters have grown and changed over time, and it doesn't take advantage of that. Perhaps, again, because of the enormous production burden developing the base levels takes up. Although, in one cutscene, modern Tails does look out at the monochromatic Green Hill Zone and say "It's like something sucked all the life and colour out of it" which is an unintentional but pretty on-point commentary on where the series went.

And even though Generations has something for you no matter what kind of fan you are, by the same token, anyone who's just there for the side scroller Sonic has to suffer through the behind-the-back play, and anyone who wants the full polygonal Sonic has to grit their teeth through the classic sections. At least when you buy a Sonic Colors or a Sonic Rush, you can guarantee it's the flavour of experience you're after from top to bottom, but that logic doesn't apply here which is likely why Sega didn't make another game like this. And fundamentally, the concept of a throwback Sonic is in conflict with what 21st-century Sonic is.

By the time Generations came out, this was an annualised franchise, and one that wasn't too concerned with stitching the mechanics and graphics of one game to the next. Mario is a series that took pains to stay close to home and whip up the same swirls of iconography and feelings every time, but by 2011, there was no codified theming or look to Sonic. There was a different hedgehog with a different gimmick for every year on the calendar. In 2005, we got to fire guns in a Sonic game; in 2008, Sonic was a werewolf; in 2009, Sonic was a retelling of the Legend of King Arthur for some reason. It was the logical endgame of creating a series based on novelty: there was a rejection of continuity, a franchise amnesia, which allowed Sonic to be contorted into whatever was cool that year rather than the developers making any attempt to stay true to an essential Sonic. And the longer you continue that strategy, the less of an essential Sonic there is.

One edge this lent to the company was that if a year's given Sonic flopped, they could shrug it off. They didn't have to marry themselves to the ideas in it and even if fans felt they'd been hoodwinked, they knew there'd be a totally unrelated Sonic along the following year. Annualised franchises generally lean in this direction, although few to no games are as fond of reinventing themselves as Sonic. By dredging up the many incarnations of Sonic from over its history and laying them end to end, Generations counteracts this strategy. Series retrospectives can be flattering if the works involved have cleared a bar of quality year after year, but in the case of Sonic Generations, the prolonged flashback sequence is a reminder of just how far the series fell and prevents the franchise distancing itself from blotches on its record such as Sonic 06 and Sonic Unleashed. There is no way for me to exaggerate how gross this game's Crisis City level looks.

Generations also reminds you of all the reasons why players may have rage quit out of the Sonics of the past. In both the prior games and this one, sometimes blindly hurling yourself off the right side of a platform is the optimal or only correct move and other times it will get you killed. Sometimes a homing attack fails to lock on, and you fall to your doom; sometimes you dash into a wall and the physics bug out, causing you to fly off the level. Sometimes pressing jump on an incline also flicks you off of the track. Sometimes holding right is just what speedrunning involves and sometimes it will lead you right into a spike trap or a robot. Sometimes those enemies shoot you from off-screen or start an attack while you're in the middle of a jump and you just have to take the hit.

Sometimes I think that we're a little too harsh on old Sonic, but no, the games actually care this little about the player. That the 3D levels keep reverting back to 2D also suggests the designers know that the side-on play is Sonic in a superior form. Maybe you wouldn't notice every metaphorical creaky floorboard and leaky pipe in each stage, but the challenge system has you scanning and rescanning every inch of every level to learn where all the jank is. Hitman maps benefit from lengthy inspection because they're built with depth and integrity in mind, but you don't want to invite that degree of scrutiny if your environments don't have the same longevity, stability, and reward for player experimentation.

And finally, because Sonic is powered by novelty, it's excruciatingly hard for a developer to fit all its historical gimmicks into one package. We have to remember that every Sonic had a different approach to storytelling from the environmentalist bent of Colors to the medieval fantasy of Secret Rings to the Final Fantasy-like presentation of Sonic 06. Their settings were also given character through their hub worlds; indispensable nexuses that tied their environments together. Video game retrospectives have almost always involve jamming a bunch of executables onto a disc and having very little crosstalk between them. Sonic Generations was being pioneering by having reimagined levels from previous games all lead off of a purpose-built hub world and run within a contiguous and original narrative context, but in doing so, it overrided the original core environments and narrative shells which are so important to the 3D Sonics.

We must also acknowledge the daunting task Sega had of honouring all the different forms Sonic has taken as a play experience over the years. Rising to that challenge involves not only splicing in the standard Sonic mechanics like spin dashing and acceleration pads, but also incorporating the team formations from Sonic Heroes, the werewolf transformations from Sonic Unleashed, the swordplay from the Wii Sonic games, and the wisps from Sonic Colors. I'm not going to say a game couldn't combine all these elements in some way, but I'm reticent to make a statement on it because it's such uncharted territory. The developers do make it a little easier for themselves by excluding the Wii Sonic games from this anthology, as well as Shadow the Hedgehog. However, Sega is still forced to mechanically prune the games left to the extent that they're giving you the opening stage from the title where Sonic famously morphs into a werehog without the bit where he turns into a werehog. It's like shipping a version of Billy Hatcher and the Giant Egg without any eggs in it. It makes it all the weirder when you reach the final world, Sonic Colors, and it does have some of the unique wisp mechanics from the original experience, as well as a colour palette that's drastically more saturated than that of the other environments.

At a certain point, implementing mechanics for an anthology of modern Sonic levels doesn't make production sense in the same way that implementing all the assets is a drain on the studio. Imagine adding one-off mechanics and characters and crafting whole new cutscenes for all six 3D Sonic games featured here when you've only dedicated two stages to each of them. Generations probably couldn't be a more expansive retrospective on the series for the same reason that the series it focuses on often comes up short: The expectations for AAA games pulled way out in front of what Sonic was capable of on an annual basis.

We can also aim valid criticism at Generations' technique of compiling Sonic experiences from over the years by using individual levels as vertical slices of those games. It's that method which means that Generations only ends up being a salute to those levels instead of to the games in their entirety, and there is a difference. No matter how fun you think Seaside Hill is, you can't reduce Sonic Heroes down to that one stage any more than you can compress Taxi Driver down to the scene with the mirror or whittle Sgt. Pepper's down to Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds. And how richly the studio recreates the core mechanics affects how true to the old Sonic games these levels can be because level design is always a response to what the player character is and is not capable of.

For a better example of a game that celebrates a series' history, and makes a little go a long way, I'd point to Super Mario Maker. The comparison between that and Sonic Generations isn't wholly fair; Mario Maker came out four years later, and consequently, was always going to have more content and higher production values. However, there were conceptual choices that Nintendo made with its game that cast it as a loving portrait of its respective series with a long shelf life. Sega could have made some of those same choices with its series retrospective. Firstly, Mario having more codified artistic and mechanical styles meant that its retrospective had more consistency, and it using minimalist stories meant that its creators didn't have to develop lavish new cutscenes to honour that series. Secondly, Mario Maker managed to stop its developers spreading their labour and resources too thin, or leaving the game too short, because it had the players create the levels instead of the studio. Thirdly, the customisable element of Mario Maker means that even when players are coming to the experience with different desires and expectations, they can still find levels that will fulfil them. And lastly, by focusing purely on the 2D Marios, Nintendo made sure that they presented one style of Mario game perfectly instead of unveiling more than one style in a half-baked form. Mario was both better primed for anthologising than Sonic, and the anthology that was created was more conscious of its limits and how to work around them.

But for all the disagreements Sonic and Mario have had over what a mascot platformer or a series retrospective should be, there is one thing that their retrospective games do agree on. It's that when looking back over a series, rose-tinted glasses can be a development strategy. Picture-perfect snapshots of a game from twenty or thirty years ago can invoke nostalgia and serve an invaluable purpose by archiving the medium even as it marches forward, but our bar of quality for games changes over time, and so there's room for games that don't just replicate but reimagine. While copying older games to modern systems can preserve the literal reality of them, revising those games can preserve the feelings we had when we first played them. That revision can happen in the form of letting players create harder and more varied levels as in Mario Maker, or it can be about fixing up the physics and cherry-picking which stages to bring back, as in Sonic Generations. Unfortunately, it's where Sonic Generations doesn't make changes as much as it where it does that show the benefit of anachronistic retrospectives. Generations has a main character optimised for fast, heedless movement but often punishes you for indulging in it, and by charting the arc of the Sonic series over time, it only becomes clearer how it's spoiled over the years and how disposable each entry has been for Sega. Thanks for reading.

0 Comments