Mythical: Video Games on the Blockchain

By gamer_152 0 Comments

Blankos Block Party is a F2P action-adventure in which you can acquire, trade, and play as off-brand Funko Pop NFTs. If you didn't understand any of the words I typed, I am so sorry for what you're about to learn. I first discovered Blankos Block Party when a twenty-minute segment on the game aired on the official E3 Twitch channel. The thing that really stuck in my head from the preview was its opening question. Mythical Games, the studio behind Blankos, asked, "Do you really own your items in games?". My initial reaction was, "No, but so what? Inland Revenue isn't coming to tax my Medal of Honor arsenal and baliffs aren't going to repossess my Roblox mansion". But the more I thought about this question, the more substance there was in it.

In the physical world, we'd generally say that ownership of an item constitutes the right to do what we want with it. I am free to use my possessions however I like, as long as it's not for something illegal or otherwise unacceptably transgressive. We have the right to modify, sell, gift, or trade what we own. In video games, we can freely exchange some goods with other players, but other items, we can't. Designers can also modify or rescind our items at their discretion, and almost never are we allowed to trade our in-game possessions for real-world money or to reprogram them.

Video games are not free markets, but I also don't see any inherent problem with that. Real-world markets and regulations are not optimised to bring us the fairest and most gratifying experiences, but video games can be. With some deleterious exceptions, like micro-transaction-driven games, the restrictions on the items we own in games reinforce the aesthetics of those titles. I can't buy as many water filters as I want in Subnautica, but if I could, it would ruin the urgent survivalism that is its bread and butter. Blizzard removed some of the older currency items from World of Warcraft, but in doing that, ushered in a less grind-based economy. Restriction, after all, is the essence of structure and challenge, which are both core concepts in many compelling games.

However, we must remember that not only do we own goods within the fiction of games but that games and their modular components are real-world goods that we own. The realities of our economy often undermines both forms of ownership. Think about MMO shutdowns. In massively multiplayer experiences, you appear to own all your items, but every one of them can be taken from you with no compensation if the servers go offline. Or you may have bought games a while back that use the SecuROM or SafeDisc DRMs that you can no longer play. Their anti-piracy software prevents them from running on many modern PCs. Some players have bought games complete with a soundtrack only to have that music expire years into the future. That's what happened with Grand Theft Auto IV and 92% of Guitar Hero LIVE's music library.

And what about intellectual property? There's an ocean of entertainment software that includes creative tools to make our own art, from custom characters to car decals. But it's unheard of that we walk away with the rights to that art. We can't sell it or license it or give it away. In many cases, our creations enhance the value of the games we create them in. This profits the companies behind the games, but we don't see a cent for it. You can see an argument that if we're performing labour that benefits a company, we deserve pay for that work.

As it stands, publishers and developers hold a vice-like grip over many of our games and their contents because, effectively, we're borrowing those items rather than truly owning them. Even if these companies wanted to give us the rights to our assets, it's not immediately obvious how they'd allow the exchange and transfer of them external to the game. Players would need universally accessible and absolute confirmation of who owns what without a patent office and outside the purview of any one company.

Thirteen years ago, some very bright engineers were grappling with a similar question. They wanted to know how people could trade over the internet without some central authority processing all the transactions. See, libertarians believe that the centralisation of economic authority in our society prevents power from being distributed among the people. After all, who controls the money, has the power. Central banks, in particular, earned the ire of right-wing libertarians as they saw a conflict between a society in which absolute authorities mint and regulate the money and the citizens achieving freedom within their own economics. The question naturally formed, "What if the people could develop their own money and their own network of trade outside of the state-controlled markets?".

The internet stood out as the most efficient medium through which people could manage and trade currency, but the outlying problem remained verifying transactions. Without a bank or payment processor to confirm users' real account balances, what was to stop anyone claiming they owned any amount of money? One answer is that we can track individual balances by keeping a list of every trade made on a network. For example, if I start from 50 credits, then I spend 20 credits, then I'm paid 10 credits, I have 40 credits.

In a computer network, everyone can be aware that I made those transactions and know how much money I have because the system can broadcast every transaction to every user. If each trader keeps a ledger of all transactions, they implicitly retain a log of every user's account balance. Of course, now the crafty businessperson would move to spoof transactions. For example, by lying and saying someone else emptied their whole wallet into the malicious actor's account. So, how do you stop people from doing that? "Digital signatures" have long existed to verify that data really came from the person whose name was stamped on it.

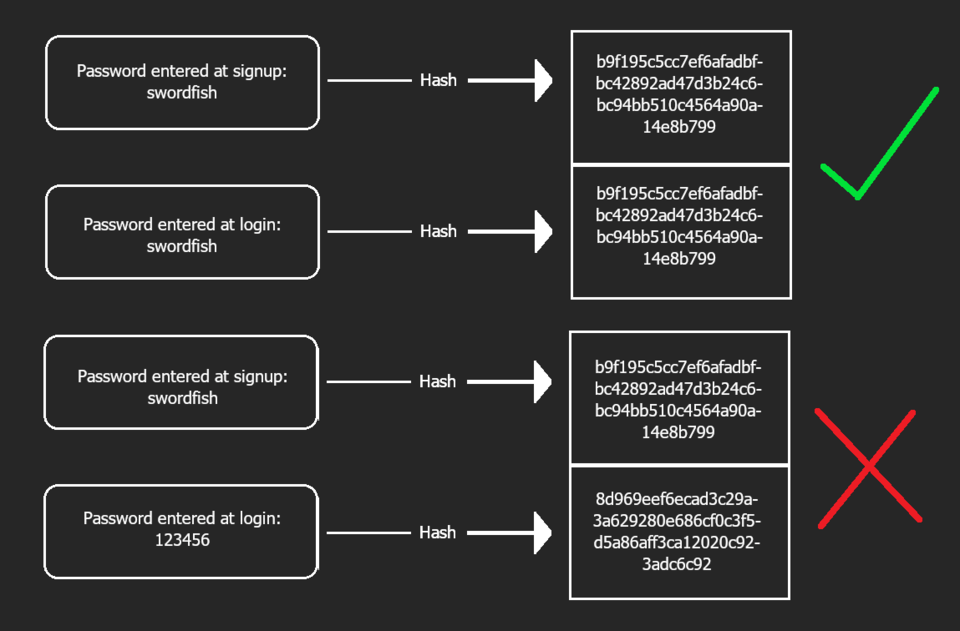

Digital signatures employ a type of mathematical operation called a "cryptographic hash function". Cryptographic hash functions take any kind of data input, be it text, numbers, images, or something else, and output what looks like a string of random characters. "Looks like" is the operative phrase here because anyone can put the same data through the same hash function and get the same result. That result is called a "hash" or "digest". If you've ever wondered why there are almost no news stories of people at tech companies breaching the password database and stealing peoples' accounts, it's because websites don't save your password; they keep a hash of it. They only know the password you tried to log in with is correct or incorrect because they compare a hash of it to the hash of the password you entered when you first signed up. If the hashes match, the password is correct; if they don't, then it's wrong.

It is also possible to stitch together chunks of data and then hash them. Let's say I had a bank safe that I wanted my employees to only be able to open at exactly 9:00 a.m. with the password "golden". When the user inputs their password, the system could then add the time to the end of that password and run the whole thing through a hash function. If you hash "golden0900" using the ubiquitous SHA-256 algorithm, you get:

a69c8fc79a79aa7abbcf35664cb484777c10355bcbd33ac60ba74eb26bb7b03a

So, the system could only unlock the safe if it sees this particular hash. Crucially, there's no method to reverse reliable hash functions. A computer cannot look at a well-generated digest and get anything more than the vaguest clue about the original input. We also have communication forms that use jumbled characters to provide secure verification over networks. In asymmetric cryptography, everyone gets two randomised strings of characters, inextricably interlinked. One is their public key, and one is their private key. One they distribute for everyone to see, the other they keep for their eyes only.

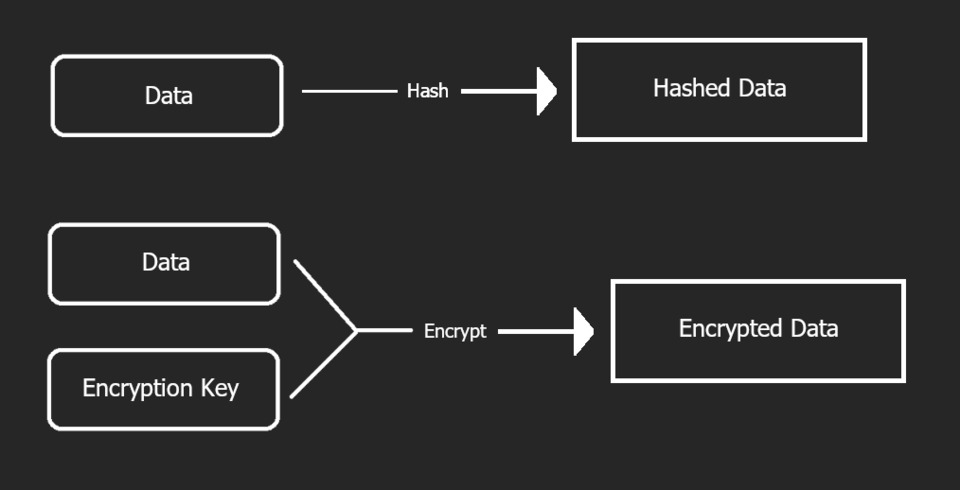

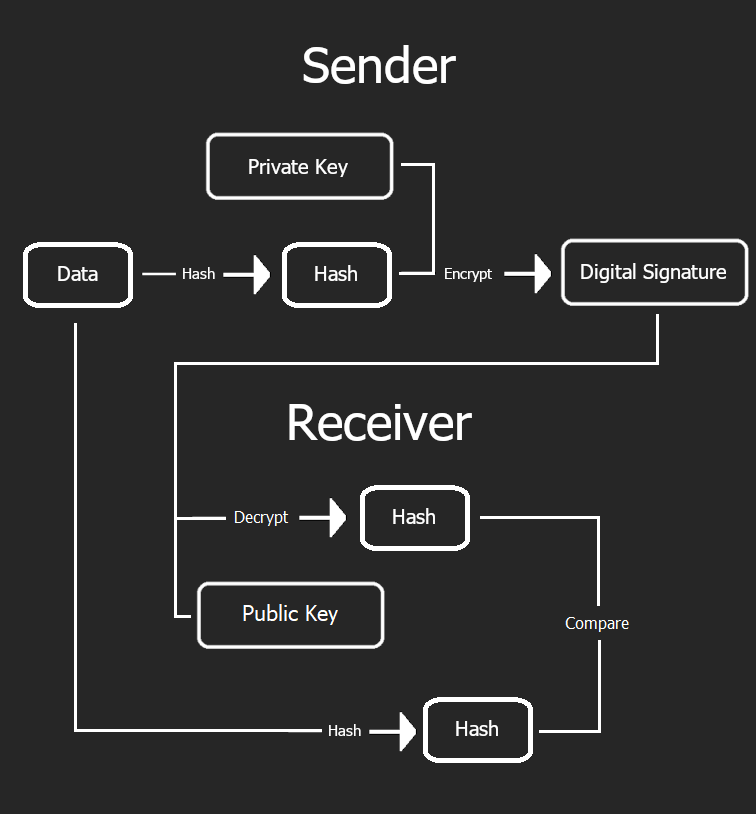

When they want to send data to someone else, they hash that data and then encrypt it with their private key. Encryption algorithms are comparable to hash algorithms: When encryption is properly implemented, the output is always the same for each pair of inputs. However, encryption algorithms use data and a specific encryption key to produce an alphanumeric output, whereas hashes only take a data input. Unlike with a hash, you can revert encrypted data to its original state, but only if you have the corresponding encryption key.

The sender's encrypted hash is their "signature". They send their unencrypted data and their digital signature to another party. The receiver can then decrypt the signature with the sender's public key to get the hash out. They can also hash the unencrypted data themselves. If both the hash of the data and the decrypted hash match, you can be sure that the data came from who it says it came from and is personally endorsed by them.

I know that's difficult to get your head around. The key idea to take away is that digital signatures can mathematically guarantee a specific set of data was approved by a specific person. In a digital currency system, users can and do use encryption keys to confirm that their address sent a certain quantity of money and the time at which they sent it. But again, a malicious actor can find a workaround. They can copy and paste lines on the ledger. Say that you paid me 10 credits at 6:01:45 p.m. on Friday. If I copy that line, complete with your digital signature, and add it to the record again, then it looks like you sent me 20 credits at 6:01:45 p.m. on Friday and signed the transaction. This anomaly is called "double spending", and preventing it was the last barrier to an authorityless, verifiable currency exchange system. Up until October 2008, no one knew how to prohibit double spending.

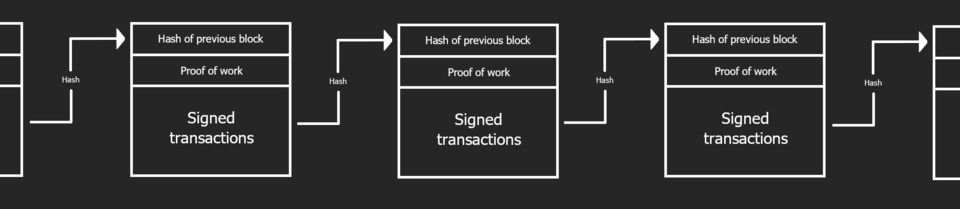

That month, a person or persons using the pseudonym Satoshi Nakamoto published a paper called "Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System". In the document, Nakamoto showed that you could split the ledger into discrete "blocks", each containing a fixed number of transactions. Those blocks would include a number such that if you hashed the whole block, the result would start with a long string of zeros. Now, no one could tamper with the contents of a block because, if they did, the resulting hash of it wouldn't start with all those zeros. Remember, different input into a hash function, different output out. That number in the block that forces its hash to start with all those zeroes is called a "proof of work" or "nonce".

But how does this protocol stop you from faking a block? What's to prevent you from making your own list of phoney transactions and then placing the appropriate proof of work at the end of it? Well, in Nakamoto's scheme, blocks do not exist in isolation. They are chained together, with each block starting with a hash of the previous block. With new transactions come new blocks. This ever-growing inter-dependent sequence of blocks is called a blockchain. Let's imagine that someone tries to edit or remove a block on the blockchain. If they do, then the hash at the start of the next block will not match the hash of the block that was edited or deleted. Users on the network will be able to tell that that version of the blockchain is fake.

There's one last piece of the puzzle before we can get a working blockchain. Remember the nonce? Well, we said earlier that you can't reverse engineer a hash. This means you can't look at a block of data and know what nonce you should add to it to get a hash that starts with a run of zeroes. All you can do is effectively guess proof of work numbers that might give you that figure when combined with the block data.

Guessing the correct nonces, every time, is not something that a single person could reasonably do. The volume of calculations, even for someone with a server farm, would be astronomical. You could, however, find proofs of work relatively quickly if you had a lot of computers making guesses at the same time. Their operators just need an incentive to set them on that track. So, in the Bitcoin system, users who find a valid proof of work for a block are allowed to add a transaction to that block meriting them some currency. It's like a slot machine where you put in computing power for the chance to win Bitcoin. This RNG to discover nonces is known "mining", and currencies backed by cryptography, like those traded through the blockchain, are known as "cryptocurrencies".

In a nutshell, this is blockchain finance. Users make transactions in blocks and digitally sign their transactions to prove their authenticity. Miners then add the proof of work, a sort of super-signature, to the block to prove that the whole sequence of transactions is legitimate. Each block then contains a hash of the previous block to prove that the chain hasn't been tampered with. If anyone doubts the veracity of a transaction or a block, they can run the relevant hashes for themselves to check they match those on the blockchain.

In around 2010, Nakamoto vanished, never to be unmasked, but their creation had an earthshattering impact. At the time of writing, the richest man in the world, Jeff Bezos, owns $201 billion, but in July of this year, Ars Technica reported that the total value of all cryptocurrencies stands at $1 trillion. The strongest proponents of the blockchain laud it as a fast-track to wealth for anyone willing to invest. They also describe it as a revolutionary technology that could underly everything from marriage to voting to video games. It is our supposed liberation from the draconian authorities of our time.

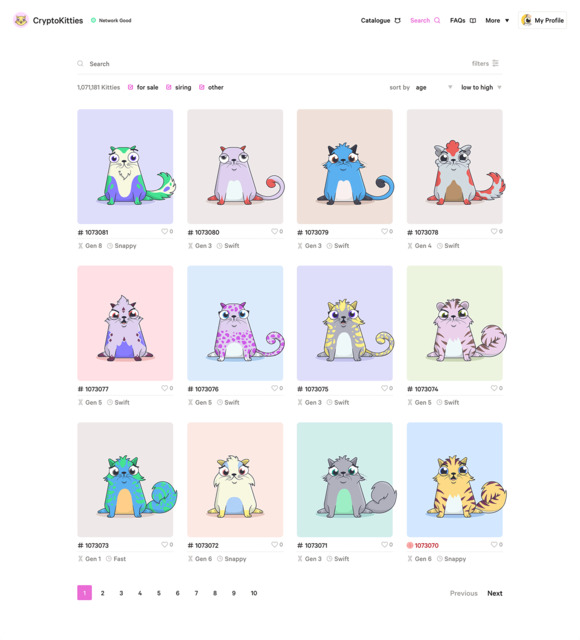

No matter your opinion on the blockchain, it has shaped and been shaped by gaming. The most influential blockchain video game was undoubtedly Cryptokitties, launched in 2017 by Dapper Labs. While the blockchain had, up to then, mostly been used to exchange currency, there's no reason that you couldn't use it to trade goods. In Cryptokitties, players can buy, sell, and breed exotic cartoon cats on the blockchain, swapping them for a popular cryptocurrency called Ethereum.

Items like Bitcoin that represent some value are called tokens. Economists would say that units of cryptocurrency are "fungible", meaning that any one is the same as any other. This concept is true for all money. No 20 peso bill serves a different function from another 20 peso bill; they're all interchangeable. But many goods aren't fungible. Paintings, plants, shirts for dogs: they're all different. So, if you were to represent these items with digital tokens, those tokens would be Non-Fungible Tokens or NFTs. This is how Cryptokitties are traded: each represented on the blockchain by a non-fungible token. That game popularised the concept of NFTs, which are now a booming market in their own right, with the most popular tokens selling for millions. Transferrence of NFTs is logged on the ledger in much the same way transference of cryptocurrency is.

NFT optimists say these tokens solve an old problem in the art market: determining provenance. The provenance is the record of ownership for a single piece of art. Who the artist traded it to, who that person traded it to, who that person traded it to, and on down the line. If you can track a piece of art back to its creator, you know it's the real McCoy. If you can only track it as far back as one owner, maybe it's because it didn't come from the supposed creator and is a forgery. But verifying that the alleged trades of a work happened is a tough investigative endeavour.

NFTs potentially solve this problem by giving you a cryptographically assured list of trades that's trivial to access. Any artist can make a unique work, valuable because there's only one of it or a few of it, and any traders of it can prove a line of ownership that runs back to that artist. The system can further allow the originator of a work to earn royalties each time it is sold automatically. Purportedly, any digital artist could see an economic windfall through this system.

While I used Blankos as an entry point to talk about NFTs, plenty of other titles picked up and ran with Cryptokitties' concept. Lost Relics is a Diablo-style RPG where the loot is bound to NFTs. Axie Infinity is a cross between Cyptokitties and Pokémon, where the creatures have NFTs. Upland is a digital landlord simulator where you buy NFTs representing real-world properties. And The Sandbox is a creation game that allows players to build Lego-like models and buy and sell tokens mirroring them in an NFT marketplace. This is big business. The Sandbox has, for some reason, featured tie-in content for The Walking Dead, Rollercoaster Tycoon, Care Bears, Avenged Sevenfold, and even Hell's Kitchen. In all cases, the blockchain's affordance of verifiable exchange allows the players an unusually high degree of ownership over what they trade.

So, we can jailbreak content from video games, right? The blockchain will allow us to finally take back ownership of what's been kept from us for so long. Well, you might have noticed that despite the best hopes of the crypto crusaders, the world banking system has not collapsed. The large majority of people do not own cryptocurrency or NFTs, and only so many of those who do are experiencing a significant bump in material control. So, we should be highly sceptical that playing games based on the blockchain will give us ownership over our items, products, or intellectual property.

Before I get to the inherent flaws of blockchain, I want to tackle a common criticism of it that only selectively applies. People say that NFT and cryptocurrency dealing are morally unacceptable because of their environmental costs. Bitcoin consumes more energy than The Netherlands one paper told us, headlines talk about it derailing the climate goals of the entire nation of China.

A lot of blockchains are power hogs because of all those machines guessing the proof of work number. Guesses require processing power, and processors require electrical power. Many of today's popular mining computers consume about 72 kilowatt-hours of electricity over the course of a day. The average American home only uses 30. And keep in mind, miners tend not just to use one of these machines but to cluster them together, pushing for the best chance they can get at extracting a coin.

However, it may be impossible to put a number on the carbon output of any one blockchain. You can find out how much work is being done on what blockchain, but different mining machines consume different amounts of power to do the same amount of work. In that list of popular Bitcoin rigs I linked, kilowatt-hour usage varies from 1.3 to 3.5, and you can't know what share of the mining operation is using what model. Simply looking at the power consumption of these units also doesn't tell us how much electricity their owners use for peripheral operations like cooling. What's more, the amount of power dedicated to crypto mining is likely to drift as electrical prices do.

Even if you can work out how much energy it takes to feed any one blockchain, that's not the same as determining their CO2 emissions. Different regions of the world use different mixes of renewable and non-renewable energy. So, depending on where you're mining or transacting, your carbon footprint is going to be pretty different from those in other locations. That's not a problem if you can tell exactly where the mining rigs are situated, but the users are under no obligation to fill you in. There's no global data for the location of miners. For the information that researchers can access, they can try to geolocate machines using IP addresses, but users can always connect through middlemen, obscuring their true IP. Therefore estimates of Bitcoin's carbon load are all over the place, and there are so many cryptocurrencies, most researchers aren't looking at the large majority of them.

Estimates of power demand and carbon output are further complicated by many cryptocurrencies forgoing proof of work protocols. Cryptokitties pioneered a scheme called proof of authority. In proof of authority, transactions are verified not by finding a hashable number but by a trusted individual or individuals. In this scenario, the authorities' incentive not to commit fraud is that their reputation is on the line. In proof of stake systems, a wealthy individual from the user pool is chosen to verify transactions, with the penalty of losing their currency if they're found faking trades. Remember, you don't have to remove money from someone's account to confiscate their crypto; you just change the consensus about how much money they have. If the network believes they lost $50,000, then they lost $50,000.

The Ethereum Foundation, which manages the world's second-most popular cryptocurrency, estimate that even using proof of work, Ethereum is upwards of thirteen times more efficient than Bitcoin. They will soon be moving their product to a proof of stake scheme that they believe will further shrink its energy consumption by over 99.9%. Even assuming a very high margin of error in both cases, that's a far cry from the inherently apocalyptic impression we usually have of crypto's climate effects. The next four most valuable coins after Ethereum also use some alternative to proof of work.

I don't want to downplay the damage here. While these proof of work alternatives deescalate the climate threat posed by blockchain transactions, it's difficult to tell exactly how much better they are without a clearer picture of crypto's effect on the climate overall. They also introduce new problems. They constitute an elaborate way to centralise an economic system that was meant to be valuable because it was decentralised. And while putting money or reputation on the line could discourage the verifiers from malicious behaviour, there are plenty of traditional economic entities who've had a lot of money or goodwill at risk and still violated the rules.

You should also know that it took Ethereum six years to move to a proof of stake system when they expected it to take them one. However, you can see that a lack of data and operational differences between blockchain technologies mean that we can't blanket classify them as a danger to the planet, nor can we be too specific about any one blockchain's toxicity. Beyond this point about the climate, I could sit here all day and spout off reasons not to use the blockchain, or churn out explanations for a lack of mass adoption, but I'm just going to run down those that tie back into gaming.

1. Having your money in a cryptocurrency doesn't innately increase your ability to generate income.

If I convert £1,000 into Bitcoin, I don't get a million pounds; I get £1,000 worth of Bitcoin. Probably less than that once you factor in transaction fees. As such, it's hard to make an argument that this currency heightens my financial freedom. You could profit through mining a proof of work currency. However, the mining market is already dominated by people who own tremendously powerful computers that can perform guesses on a godlike volume. Your little home PC will not keep up.

2. A related issue: The blockchain doesn't stop a large amount of currency from concentrating in a few hands.

Around 2% of all entities on the Bitcoin network control 72% of the currency. It sounds like the power is pretty centralised to me.

3. Another related problem: Crypto markets exist as a subset of the larger world economy rather than sitting in some closed system.

So, the most wealthy in traditional currencies have the most power to control cryptocurrencies. Those with the least wealth outside crypto are the least equipped to make money with it from the get-go.

4. There's a security issue.

If someone gets your private key, they get your account. This isn't like when a fraudster targets you, and your bank can intervene. The whole point here is that there's no central authority, and as it stands, there's almost no crypto regulation. In a world where even established tech companies have been the victims of a hacking epidemic, this poses a problem. If your account is compromised, you're never getting it back.

5. There's an anonymity issue.

If anyone can connect a person to a crypto wallet, then the world can see the entire transaction history of the wallet's owner and always will. You cannot erase data in the blocks, remember. The transaction history tied to your public key may even serve as a clue to anyone trying to unmask you.

6. Crypto has become closely connected to criminal activities.

As the value of these currencies rises, so does the value in the pockets of many criminals. I'm not talking about benign crimes like selling weed; we've all heard about the people who use crypto to anonymously ransom targets or scam the vulnerable.

7. The price of cryptocurrencies tends to fluctuate wildly.

It's less than ideal if the cost of your groceries skyrockets overnight or if, over a week, the value of your labour halves. Every currency is worth what you can exchange it for, and very roughly speaking, it's supply and demand determining a commodity's worth. But people won't suddenly demand twice the food, and not every car mechanic in the world will supply half the labour overnight. So, the dollar, which you can exchange for commodities like food and cars, stays stable, at least relative to a cryptocurrency. The crypto, typically not backed by commodities with stable supply and demand, becomes unstable and doesn't have these moderating factors to batten down its worth.

Then there are a few criticisms that apply specifically to NFTs.

1. NFT art is, in most current implementations, easy to pirate.

While marketplaces sell NFTs on the understanding that they are verifiably unique, NFT art is far more easily copied than a physical painting or statue. Because art marketplaces have to show what you're purchasing, you can go to NFT stores and download the image or video they're selling without buying it. This also makes it simple to bind an existing popular work to a different NFT and sell it on. Any intervention to stop this happening would constitute the regulation that blockchain was invented to avert. It's probably for the best that the NFT art isn't unreplicable, however. If there were only one version of each of these files in the world, that would gate many people from access to the art.

2. Related: Because cryptocurrencies exist away from the watchful eye of authorities, there's not a lot of legal recognition of ownerships acquired through the blockchain.

This is an issue for NFTs; if the copyright system doesn't recognise your right to a product you bought on the blockchain, and you don't have a license to it, do you really own it? What are you going to do if someone steals it? As if to prove that point, an army of bots has been automatically minting other peoples' art into NFTs so that the bots' masters can turn a profit. This, again, disproves the whole idea that NFTs ensure that work sold is unique and legitimately owned by the seller. Remember, what's verifiably unique is not the artwork; it's the token that represents it.

3. In current implementations, buyers of NFT art risk losing access to it through no fault of their own.

If your access to your art is a link in a metadata file, what happens when the server hosting that file goes offline? NFT sellers aren't unaware of this issue and usually use a peer-to-peer file system to store art, allowing anyone to access the piece as long as it's saved somewhere on the network. However, not only is the existence of all these copies proof of the reality that NFTs do not grant exclusive ownership, what happens if there's no one left on the network hosting your file? Even today, gremlins in the wires are fraying the connections to blockchain art. Check My NFT found links to pieces from even major NFT artists like Grimes and Steve Aoki non-functional. You could argue that if you bought the Mona Lisa, you wouldn't get a backup version, but then the Mona Lisa can't be destroyed in a hard-drive crash.

4. NFTs may only serve the very top end of the art market.

These commodities solve an authenticity problem, but these authenticity and provenance issues almost exclusively affect the most expensive artworks. Checking for forgery is something you do when you're procuring an original Gaugin or Vermeer, not your first step when you're purchasing from your favourite artists on Etsy or ArtStation. In fact, in the latter cases, you can usually buy directly from the artist anyway, so if you do care about authenticity, you're already covered. Of course, it's the former works that are the more expensive.

I don't see most digital artists complaining about an issue of provenance, and that's probably because it doesn't apply to their field. Most people buying art don't care about the uniqueness of the work. If I have an Aurahack piece, why do I care that someone else does too? It's only once we enter the world of the ultra-rich art traders that scarcity is sought after because scarcity drives prices.

___

You might ask why there is an animated market for crypto and NFTs if they are such sorry substitutes for traditional currencies and digital goods. We must understand that, for profiteers, the above issues aren't really flaws. Sometimes, they're even desirable. Let's return to point number seven about crypto: its instability. If booms and busts in a currency market can occur in the space of weeks, then investors in that market can make small fortunes in a handful of days. The volatility of the currency isn't a bug; it's a feature. Buy when it's comparatively low, sell when it's comparatively high.

A commodity doesn't have to be useful to be valuable, it just has to be something people want; that's what valuable means. So, as more people buy up a coin, and it becomes clear it's in demand, sellers can jack up the price for it. As the commodity's worth increases, more people buy it up, which causes the value to increase further, and on the feedback loop goes. Most of the people buying up a currency like Bitcoin are doing it precisely because they expect they can trade it onto other people who will pay more for it: this is speculative investing.

Of course, somewhere in this chain of high stakes pass the parcel, someone will be looking to sell their crypto at a higher rate and find there are no takers. Past a certain price, prospective buyers fear they won't be able to sell the currency on and so don't purchase any more of it. People who do own it can only sell at a loss, and when it becomes clear the value of the currency is falling, everybody tries to offload it at once, only causing the price to drop further. This is the speculative bubble popping. It's how people lose a lot of money investing in crypto; they end up selling on the wrong side of the crash. Again, an item is worth whatever you can exchange it for, so if it's these currencies that you directly exchange for NFTs, the value of the NFTs fluctuates with them.

The upshot of all this is that the NFT market isn't optimised for people who want to own and exchange practical or aesthetically appealing items; it's optimised for people who want to make a buttload of money off of it. There's little reason for anyone who cares about art for art's sake to invest in the blockchain because it does not secure art for art's sake. What it does is allow receipts for digital goods to be passed about by traders to the same ends that stocks and bonds once were. This isn't an art market mediated by cryptocurrency; this is a cryptocurrency market mediated by art. If cryptocurrency is the currency of decentralised digital trade, then NFTs are its securities.

We haven't talked about video games in a hot minute, but you can see how many of the observations here would answer our question from the start of this article. Any platform that does not grant us legal rights to our "posessions" is a compromised solution to ownership. In fact, most of these NFT game studios are forced to admit what you do and do not own through their terms of service, and it makes for disappointing reading.

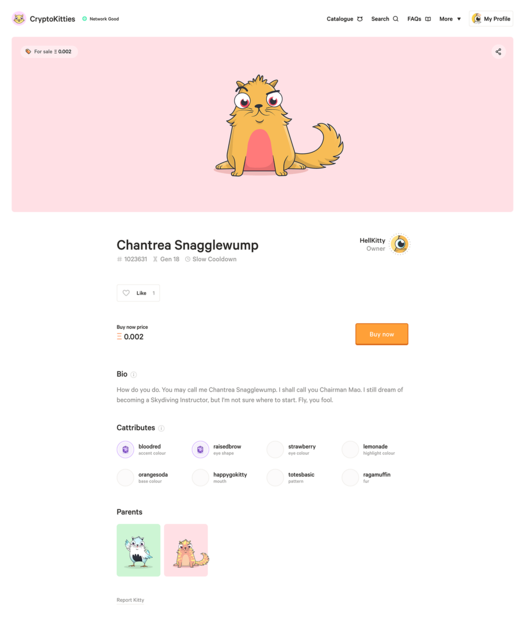

The Cryptokitties ToS states that you really do own your assets from the game and can sell them to whoever you like. You can use them in a personal capacity or for your business, provided it's making less than $100,000 annually. You can't, however, license your kitty out to anyone else. In The Sandbox, you do own your assets, but the developers retain the right to use and modify your creations however they like, including employing trademarks you own in conjunction with them. Upland, that game about trading real-world properties, owns everything you submit to it.

It's Blankos Block Party, however, that best shows how little control over your items a game can give you while still functioning on the blockchain. You do not have the right to use one of your bootleg Funko Pops outside the game in any way. You cannot modify their design, place them in any media, or acquire IP rights for them. The software uses a proprietary currency called Blankos Virtual Currency that can only be traded in the game and cannot be exchanged for any actual currency outside it. Mythical retain the right to confiscate all this currency whenever they want. You can sell your Blankos in online marketplaces outside the game, but the company effectively controls the entire secondary market and takes a fee from every trade. Mythical further lay claim to the right to reverse or cancel trades at their discretion and to terminate whoevers' Blankos account they want.

A recurring pattern in these terms of service is that by granting ownership of an item without extending rights to the intellectual property associated with it, these games don't let us "own" much at all. It makes me think that in the case of creative blockchain games like The Sandbox's, their purpose isn't so much to unshackle our creations from faceless tech firms, but to take spaces of free artistic collaboration and commercialise them. And that, in the case of other game markets, blockchain finance is taking recreational economies and rebuilding them in a manner that would earn developers real-world commission on them.

In addition to being shaky business propositions, blockchain games potentially embroil you in a whole new set of issues that traditional games don't. For example, the indestructible paper trail of your transactions or the potential environmental costs. Blankos may use a proof of authority system, but if an authority regulates our ownership and transaction, then this game doesn't allow us to squeeze our items out from under the thumb of huge organisations as it claims.

Tying items in a game to a volatile currency could also gate our access to them. Under such a system, the prices of goods wouldn't be set by designers looking at what's fair but by market forces that we have no control over. And if you can't control those markets, how can NFT-based games promise more control over your items? When we discuss ownership, we often spend more time talking about securing our existing possessions than gaining access to anything new. But a game does not enable ownership if the price of the goods leaves them well out of our reach, and whatever assets we own may disappear when the game goes down.

Further, those who promote NFTs often do it on the grounds that they abstract all goods into a single, standardised, and thus, easily exchanged form. So, that makes it sound like that technology would enable us to extract items or art from a video game, and thus, retain a hold on them. But as a NFT is a token representing a good and not the good itself, it can't force items or art to transcend any existing rules that govern them.

Almost all digital media needs some software interface to make it dance. For example, image files need picture viewers, and video files need video players. Fortunately, both are easy to come by, and almost any viewer or player will do. However, video game items and art are not so software agnostic; they only run in conjunction with the specific games for which they were developed. As such, it's hard to imagine legally breaking the content out of any non-open source game. Even in a title like Cryptokitties, which is about as generous as NFT games get, you can't breed a Cryptokitty, an essential feature of the kitties as an asset, without the developer's patented algorithm. No Cryptokitties, no Cryptokitties.

I've spent a lot of time talking here about the technological and economic realities of the blockchain. I could have written this essay without doing that, and it would have been more approachable and to the point. But if blockchain is going to be a force on the economy we live in, and especially if we're going to consider interacting with media based on the blockchain, it's worth ripping the tech open and taking a gander at its innards. You shouldn't sign a contract without reading the small print. You shouldn't take out a loan without knowing what APR is. Mythical Games emphasise that you don't need to understand the underlying algorithms to play Blankos, but if you're interacting with the blockchain, you should be conscious of how the blockchain operates.

I think this demystification is particularly important because the proponents of crypto are so loud they're deafening, and what they say often implies there's some "get rich quick spell" contained in the blockchain's logic. A discourse has grown around this technology and its assets: half religious proselytising and half pyramid scheme pitch. This discussion is now encroaching on the games industry. In the mind of the most pious traders, we must invest obsessively and uncritically in the idea that the blockchain, like a benevolent deity, will deliver us wealth and freedom. Anyone who says otherwise lacks sufficient faith in the system. But when we unpack the blockchain, we see that it's not magic and it's not a god. The system is elegant, and it's ingenious, but it contains no golden bullet for exerting economic control. For now, your virtual items won't be ascending from their respective video games. Thanks for reading.