Peripheral Vision: An Analysis of Rock Band 3

By gamer_152 0 Comments

If you've been following this series of articles from the start, you'll know that Harmonix laboured for a decade and a half to release a game that was both significantly profitable and critically well-received. You'll also remember that their breakout success, Guitar Hero, was snatched from their clutches in an Activision buyout, but that they managed to avert disaster through developing Rock Band 1. If you stop retelling their history there, it sounds like the story of a rhythm game underdog graduating to global popularity, but look at the sales data, and you realise this is about them experiencing mainstream success for only a fleeting instant before descending into what CEO Alex Rigopulos described as a "sustained horror show".

The original Rock Band was actually the commercial peak for the franchise, with Rock Band 2 raking in less than 1, and The Beatles: Rock Band making less than 2. The band game format had been invented in 2007, but by as soon as 2009, it was about ready to wink out of existence, which was a little unexpected when it was still wedged deep within the public consciousness of the time. If you ask people how the genre reached death's door, they'll generally tell you "oversaturation", but it's a little more complicated than that. Yes, the market did become oversaturated, but these band-based products were always going to be more susceptible to that than conventional video games. Rock Band was a risky venture from the get-go.

New adopters for the games had to pay well over £150/$150 for an instrument bundle and had to dedicate no small amount of in-home space to those peripherals. If a controller broke or the owner just wanted to upgrade, they were also looking at hefty fees. Now, it's hard to tell exactly how much these factors played a part, but you've got to believe that consumers wouldn't have treated buying a Rock Band or full band Guitar Hero game the same way they would have thought about buying a standard £40/$60 AAA title that required trivial storage and living room space.

It's also true that the western territories that Harmonix and Activision were targeting were undergoing a recession from 2007 onwards, the exact period in which the industry was establishing the band game genre. And while both these companies are guilty of flooding the market, the damage Harmonix did pales in comparison to that of Activision's. If we're counting releases for both home and handheld consoles (but excluding arcade machines or mobile games) then from 2007 to 2009, there were five Rock Band games. In the same period, there were twelve Guitar Hero games. Outside of mobile development, I've never heard of a series releasing twelve games in three years.

It's also not as if Harmonix kept making Rock Band games oblivious to the market drowning in copycat products. Alex Rigopoulos said of Rock Band 3 "Our ambition [...] was really to re-energize and reinvigorate the (music game) category and advance it and move it forward". The perspective here is not one of a CEO continuing business as usual, even with the rhythm genre sky falling, it's of someone who considers the genre to be stagnating and wants to reboot the format. And it's not all talk. When Harmonix released Rock Band 3 on us in 2010, it upended the hardware conventions and feature set of the series with a revolutionary attitude none of the previous sequels had. It expanded the experience with deceptively simple logic: If Rock Band is a rhythm game about overlapping play between multiple instruments then the most conceptually simple upgrade you can make to the game is to add another instrument, and the one widely utilised rock instrument missing from Rock Band was the synthesiser.

The Keyboard

Of course, jimmying in another peripheral is easier said than done. Manufacturing multiple controllers was one of the most strenuous challenges of developing Rock Band, and every time you a new added one, you drove up the price for the full set of instruments. However, by Rock Band 3, Harmonix had had some practice at getting plastic in players' hands, and most fans owned a reliable guitar, mic, and set of drums, so they wouldn't need to buy the whole hardware suite all over again. This made for a gentler introduction of the synthesiser; it was only one more item for audiences to purchase.

You'll remember that Rock Band always simplifies real-world instruments so that lay people can play them, and in true fashion, the synth consists of a couple of octaves of a standard keyboard capped with an extra C. If that sounds like gobbledygook to you, don't worry too much; the important thing to remember is that this is just a slice of a professional keyboard. Of course, every Rock Band instrument worth its salt tests the player in a way that the others don't, and the synth examines our aptitude at moving our hand left and right across a set of buttons as a song moves up and down in pitch.

You might be thinking that the guitar and bass already had us sliding our digits along a shelf of buttons, but at most, you moved one fret over with each shift, and those instruments cared a lot more about precision. The keyboard, on the other hand, is a twenty-five button peripheral split into five coloured sections, and you have to hit a key within one of those coloured portions as prompted. With large target areas to press down in, imprecision is often not punished as it would be on the guitar or bass. However, even if you ignore the black keys and just play the ivories, you have to move up to twelve keys up or down the keyboard at a time. You'll also notice that the orange section of the synth, which is used almost exclusively on Hard and Expert difficulties, consists of a single key, ensuring that Hard and Expert ask for a laser precision other modes don't.

Pro Instruments

If the most obvious way to add onto Rock Band is to implement new instruments then the second-most obvious is to build parts onto the existing music hardware, and this is how the "pro" guitar, drums, and bass found a home in Rock Band 3.

The Drums

The pro drums add three plastic cymbals above the existing pads. Up until this point, drums and cymbals had both been represented using the four coloured pads meaning that the designers often had to get crafty to simulate a real kit. E.g. During the chorus of a song, the yellow pad may represent a tom-tom, but during the bridge, it may morph into a hi-hat to adapt. The transformation can be a little jarring, but more to the point, the standard drumkit suggests that smashing a drum feels the same as striking a cymbal and that's not true-to-life.

The pro drums finally acknowledge the tactile difference between cymbals and drums, and while the four drum pads are at roughly the same height and right next to each other, the cymbals are at differing elevations with non-uniform spacing. This challenges even the virtuoso Rock Band drummer by forcing them not just to think about where on the instrument they're hitting along the X-axis, but also now, the Y-axis. Slamming on one of these new platforms might not be challenging when done in isolation, but you have to be able to move seamlessly between the cymbals and drums while keeping to the rhythm of the song. Note that none of the cymbals slots into the kit directly in front of the player, creating a gap through which they can still view their television.

The cymbals are coded blue, green, and yellow, and by having all of them share a colour with one of the drums, the game can radically simplify the UI for them. Instead of having a note lane for every drum and cymbal, the cymbals use the existing lanes that match their colour but represent themselves with a circular note as opposed to the rectangular notes which denote a drum strike. Put another way, the game had previously distinguished drum inputs by colour but now uses colour and shape to do so. This betrays the design philosophy that Rock Band 1 set out. In the original game, notes were oriented on the track to give the player a physical sense of where they should be striking the drumkit, but in the pro UI, the cymbals occupy the same spots as many of the drums; there's no sense of them being above the pads. If we want to play devil's advocate, we can, however, say that most players buying the pro drumkit are going to be dedicated enough that they will likely overcome any unintuitive commands in the UI.

The Synth

But where does that leave the synth? It's cost-effective and not that demanding on the consumer to sell them three cymbal pads but larger keyboards are pricy and have a massive footprint in a room. Fortunately, because Harmonix created the keyboard at the same time they introduced the "pro" feature, they can have the pro synth functionality built right into the base instrument instead of requiring you to go out and buy a new peripheral. The pro mode on the synth has you not just aiming for the coloured sections as you play, but hitting the exact keys that would sound those notes in the song. In this mode, tinkering with the synth becomes more about dexterity which means it does start to blend into the guitar and bass conceptually, but it has a completely different feel to them. You place the keyboard on a table or your lap in front of you and play with your palm pointing away from you, whereas when playing the guitar, you hold the peripheral across your body and press down buttons with your palm facing towards you. On the keyboard, you also have the unique task of getting your hand around the raised black keys, sometimes while simultaneously pressing down on the lower white keys.

We should note that while the pro guitar, bass, and drums are close approximations of their real-world cousins, if you're learning keyboard as an instrument, one of the trickiest tests of your co-ordination is being able to use your left and right hands on the keys independently of each other. Rock Band 3 does not simulate this challenge; the synth peripheral is not long enough for you to play with both hands and it's not something the UI can facilitate. However, there's some accuracy in this inaccuracy. The synth parts in the game, while they don't have a left hand, are still often 1:1 recreations of what the keyboardists who performed these tracks played. There is no left-hand part essentially because the left hand in a piano piece typically provides the rhythm and bass for a song, but in rock music, you already have a drumkit and a bass guitar to do those jobs. So, these songs can get by only including a right hand or melody part for the keyboard.

Another problem Harmonix faced was fitting all those keyboard inputs into a graphical interface. It's easy enough to do that with the drums where there are eight inputs, all unique, but the synth has twenty-five keys that break down into only two types, meaning there's no easy way to compress down the relevant data on what to play. Remember, not only is a GUI with a lot of channels on it overwhelming for the player, but you also couldn't fit it onto the screen alongside two other note highways. Harmonix rises to the task by having the note board for the synth slide left and right as the song goes on to encompass only the areas the player will be working in. This is possible because the game only needs to display the notation for one hand at a time; it would be right out of the question if a left hand was involved.

The Guitar

If you think the pro drums or the keyboard are complex, you haven't seen anything yet. The pro guitar comes in two forms. The first is a guitar controller manufactured by Mad Catz that has one-hundred-and-two buttons to emulate every place you could hold down a string in conjunction with one of seventeen frets (6 strings x 17 frets = 102 buttons), as well as six strings on the guitar body to strum. Then there's an actual twenty-two fret guitar from Fender with touch sensors situated under each intersection of the strings and frets. Effectively, the pro guitar mode not only increases the number of frets from five to seventeen (or twenty-two) but also introduces the concept of strings to the play, drastically increasing the level of manual aptitude the player must display. Thought of another way, the original guitar peripheral effectively had one string, while the pro guitar has six.

To play bass with either of the peripherals, you simply use their top four strings which is never going to feel exactly like an authentic bass because the actual instrument has its four strings spread out across the whole neck and not clumped together around the top. However, with the Mad Catz Mustang launching at $150 RRP and the Fender Squier Stratocaster at an effective $310 ($280 for the guitar and $30 for the MIDI adapter that lets it interface with a console), expecting consumers to purchase separate guitar and bass peripherals would have bee more absurd than ever. You may also have worked out that as the Mustang has five fewer frets than the Squier Stratocaster, you cannot play the full guitar part for every song with it, but there is some trade-off. As the Mustang has plastic buttons instead of metal strings, it doesn't hurt the player's fingers, and the owner will never have to replace snapped strings. For whatever reason, both guitars also lack whammy bars.

In adding more complex electronics to the Rock Band stable, Harmonix threw the series back to the production troubles of the original game which was plagued with long gaps between release windows. While the Mad Catz controller reached shelves on the month following Rock Band 3's launch, the Squier Stratocaster's release was delayed, and it didn't come out until May 2011, six months after the game's launch. The developers working on the software side had also had their work cut out for them. There's probably no way to quickly convey to the player which of up to one hundred-and-thirty-two inputs (22 frets x 6 strings = 132) they need to enter at any one time, especially when they may need to hold down multiple inputs at once. Developers Jason Booth and Sylvain Dubrofsky would need to solve this issue as they designed the pro guitar mode. The two first experimented with a system wherein each lane of the note highway would correspond to a different fret on the guitar and where different coloured gems would each correspond to one of the six strings. A similar prototype used numbers instead of colours to indicate the correct string to hold down. I don't believe there's a world in which these interfaces would have made it into the final product.

The colour system only worked in previous Rock Bands and Guitar Heros because areas of the instruments were painted with those colours. You can see which drum is the green drum and which fret is the red fret because of the markings on them; there are no such markings on the strings of a guitar and there's nothing intuitive about the idea of the third string down being a blue or a yellow. The system of numbering the strings gets closer to the mark, representing the fifth string down with a "5", for example, but if you're going to have a single lane on the highway for every fret, you're going to need twenty-two lanes. Sure, the keyboard might be capable of twenty-five lanes, but you can represent more of the keyboard in a smaller interface as the white and black keys share much of the same space. Plus, the keyboard doesn't have the complication of the strings.

Booth and Dubrofsky's solution was to re-orient the board. Instead of looking at the guitar horizontally with a lane for each fret, the player would look at it vertically with a lane for each string. The gems on those lanes each have a number affixed to them which signals the fret that the player is supposed to play. So a "5" travelling along the leftmost lane means the player must place their finger on the fifth fret of the topmost string while a "7" travelling along the rightmost lane would mean they have to play the seventh fret on the bottommost string. This was a solid system for having the players perform arpeggiation, the act of sounding out each note of a chord on its own. However, asking users to play entire chords at once with this setup would have only baffled them. For example, requesting the guitarist to play a C major chord might end up being conveyed by a "3" on the second string, a "2" on the third string, a "0" on the fourth string, a "1" on the fifth string, and a "0" on the sixth string all simultaneously. That's a lot of information for the player to decode at once, especially if your entire song is going to be using that chord format.

In solving this problem, Booth took inspiration from the "Brain Wall" segment of the Japanese gameshow The Tunnels' Thanks to Everyone, better known in English as "Human Tetris". In this game, a wall with a hole in it approaches a player, and they must contort their body into the shape of the negative space to pass through it. Booth implemented a similar principle involving the guitarist stretching their hand to match a shape on the note highway with the game providing constant feedback on their current fingering. When pro mode wants you to play a chord, a numbered gem comes down the note highway which lets you know which fret you must place your forefinger on. A line extends to the right of it which moves up and down across the strings like a mountain landscape.[1] The elevation of the line as it passes over a string lets you know how high up the fretboard you must place your finger on that string, using your forefinger as a reference.

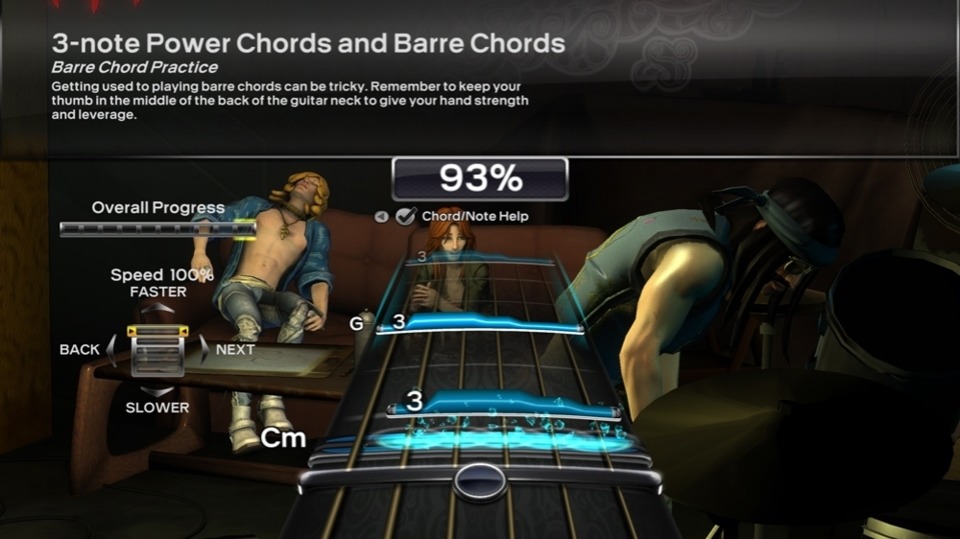

The game also relies on the fact that the notes we play within a song aren't just random; they conform to a set of chords with a rock song usually using around four chords for the whole piece. Players in Rock Band 3 have the option to force chords to display alongside the note highway, similar to how they are projected on real sheet music. Users can also look up the chords involved in each song in-game or run through a set of tutorials on tablature and technique developed between Harmonix and the Berklee School of Music. There was always going to be a sharp learning curve for the pro guitar; playing it is volumes more complex than anything in the original game, but with so much thought put into its introduction and interface, the experience is still more encouraging than trying to learn guitar on your own.

Summary

As a collective, the pro peripherals help players forgo one of the most demotivating aspects of learning to play music. For the first few weeks or months that you're learning an instrument, it sounds hideous. You can make huge strides of progress and still get very little positive aural feedback. With the pro gameplay, Rock Band does what the series does best: it allows almost anyone to feel like they're playing music and to make exciting sounds from their earliest sessions. Rock Band 3 is also a landmark achievement for the music game genre because, more than any other rhythm game before it, it blurs the line between controller and instrument. Not only is playing the pro instruments on Expert close or identical to the process of playing music outside the game, but many of these peripherals can also be used to create your own music.

The Squier Stratocaster can output sound to an amp, and while the word in the community is that the Squier is a shoddy analogue instrument, both the Mustang and real guitar are capable of MIDI output, giving players access to reliable, low latency MIDI guitars. The keyboard can also output in MIDI, and a twenty-five key synth is the exact kind of device that can get a budding artist started in electronic music. At $80 RRP, there are cheaper solutions on the market, but a wonderful feature of Rock Band 3's MIDI adapter is that if you have a MIDI synthesiser you prefer, you can use that too. You can also use any USB mic with Rock Band, and while Harmonix has never been vocal about it, the USB connection on the old Rock Band drums means you can plug them into a PC where you can use them in conjunction with your own PC software. Additionally, since Rock Band 2, you've been able to use special drum brains to connect your own electronic kit to Rock Band.

Harmonix could have made it so that audiences learned to play an instrument in Rock Band 3, but that they would then have to go out and purchase another pricey piece of equipment to continue their journey with that music. Sadly, when you force people to do that, a lot of them can't or won't take that next step and graduate to playing music for themselves. However, Rock Band 3 makes it so that qualifying from instrumental karaoke to authoring your own tracks simply means plugging your controller into a different machine. One of the saddest tragedies of Rock Band 3 is that the MIDI adapter and pro guitars, being specialist products, were manufactured in limited amounts, so they are highly expensive today and in the future may be impossible to own for even the most willful of games enthusiasts.

___

Vocal Harmonies

While all the instruments were awarded pro modes, the vocals weren't and never could have been. You had all the equipment you needed to sing in Rock Band like a professional from the start, but that doesn't mean that this sequel didn't introduce something new to the mainline series for vocalists. The recurring mechanics of many game series are not just the product of the general theming of the series. Some of them existed for one-off games with a specific theming, but players loved them so much within that context that they then became a permanent fixture of the series.

For example, Assassin's Creed III introduced the activity of free-running through trees to impart the connection to and knowledge of nature that its Native American protagonist had. But the mechanic allowed for such increased interactivity with an organic environment that it stuck around for the following games. The vocal harmonies in Rock Band 3 and 4 exist for similar reasons. The mechanic allows up to three players to sing on a track simultaneously, each taking on a different vocal part of the song. It was The Beatles: Rock Band that first introduced vocal harmonies because intertwining vocalising was an unmistakable mainstay for the band and because Harmonix needed to represent every Beatle member's voice in the game both figuratively and literally. The broader application of it, however, is obvious.

The Soundtrack

As happens with many titles, improvements in some areas of Rock Band made development tougher in others. When putting together a rhythm game soundtrack, you often have a helping hand: the most popular songs in every mainstream music genre have been well-documented, and you can use that popularity as a guide. The problem for Harmonix was that because they'd been releasing new tracks every week for three years, they'd already covered a lot of the crowd favourites. Within the narrower wedge of rock music they could pull from, they were locked out of many options because they needed an armful of songs that brought both vocal harmonies and the keyboard into the fold.

The song listing they ended up with includes shoe-ins to please the average headbanging rocker like Here I Go Again by Whitesnake or Get Free by The Vines. Yet, far more often, the need to work within the constraints of Rock Band 3 has Harmonix reaching for deeper cuts and flaunting enviable curation skills. The soundtrack they produce feels closer to a playlist someone made for you than it does a licensed soundtrack. There's Yes's jaunty prog jam Roundabout, Tegan and Sara's naked document of emotional collapse The Con, and seafood-based camp rock with The B-52's Rock Lobster, to name just a few. There are also certain songs which invite epic communal gatherings like Space Oddity by David Bowie and Bohemian Rhapsody by Queen. These songs wouldn't come at you with the blusterous force that they do if it weren't for the inclusion of the keyboard and vocal harmonies; it's impossible to imagine these tracks without them. Although, once you've seen the synthesiser, you do notice where older Rock Band tracks contain synth parts but don't include them in the play. Harmonix did retroactively add keyboard play for a number of these tracks, but you had to pay a fee for that addition, and the coverage was never universal.

Harmonix also committed a minor blunder in letting gaming publication Gottgame leak their soundtrack a while before release. The leak probably wasn't intentional on Gottgame's part: In a video posted by the site, their editor Steve Masters interviewed Rock Band 3 project lead Daniel Sussman while, in the background, a player scrolled through the tracklist of a pre-release version of the game. In response to this, Harmonix put out a humorous video from Gamescom in which then-director of PR and publishing at Harmonix, John Drake, condemned sites like Rock Band Aide and Giant Bomb who reported the leak, while Sussman flicked through the full library of Rock Band 3 tracks on a widescreen TV just behind him, implicitly confirming the on-disc catalogue. In the words of Drake:

"We are communications professionals. We would never make a mistake and accidentally leak 83 songs well before our game comes out totally by accident because we weren't paying attention".

Other Features

While Rock Band 3 is mostly about new instruments, upgraded instruments, and a left-field soundtrack, there are some surprisingly effective quality of life improvements in here. Firstly, the game allows players to quickly switch their profiles between instruments without having to sign out on one peripheral and sign in on another. It's what you need to be able to do to play a game in a social setting where people are going to want to drop in, drop out, and switch between pillars of play. You'll also find that when you finish a song, the interface tells you what percentile of the leaderboard you landed in. This is far superior to giving a leaderboard ranking as many designers do because that number doesn't tell you how talented you are relative to other players. At least, not if the game won't tell you how many other players there are, and once it's given you both numbers, it might as well also crunch the maths to tell you how they fit together. Knowing I'm in the top 40% of drummers on Everlong is far more meaningful as a statement than knowing that I'm #14,593.

Lastly, Harmonix stitches the game together with more scenes that suggest you're part of a touring band instead of just periodically accessing a band mode. The main menu has your musical group walking the city streets, you can see them in the background of difficulty selection screens hanging out on planes or in limos, and loading seams are hidden with a few seconds of your group going through a drive-through or having their stage constructed.

The Aftermath

Rock Band 3 is Harmonix's most complete effort to live up to their mission statement of providing audiences with accessible music tools and making them feel like they're playing real instruments. That sizeable gap between playing with the controllers on Expert and playing the actual piece of kit is gone; the developer has laid down a path that can take a player from awkwardly strumming their way through In Bloom on Easy to playing heavy metal on a real guitar. This is also the rare game which expands both the depth and scope of a genre simultaneously. Between the pro and basic peripherals, Rock Band 3 emulates eight different instruments and allows for up to three vocalists to sing alongside the rest of a band. It sees the series push the song count well over the 2,000 mark and challenges you to broaden your tastes with its colourful soundtrack. At the same time, you can put more hours into Rock Band than ever, trying to perfect your ability with these instruments.

So what was Harmonix's reward for this innovation? Rock Band 3 sold fewer copies than even The Beatles: Rock Band which, remember, grossed less than any mainline Rock Band game. While Viacom originally purchased Harmonix for $175 million, they wrote off a $200 million loss from the Rock Band franchise. Two months after the Rock Band 3 release, Viacom sold Harmonix. It was widely reported that the developer was bought up by Russian investment firm Columbus Nova, a potentially controversial business deal, as in 2018, the largest client of Columbus Nova was sanctioned by the U.S. government as part of a pushback against the shady business practices of Russian oligarchs. Bizarrely, even though Viacom themselves publicly claimed that they sold Harmonix to Columbus Nova, the developer says that this was pure fiction and that over the years, they've been trying to correct the record. Then, four months after Rock Band 3 launched, its publisher, MTV Games, shut down. At this point, the game had sold only 800,000 copies. Harmonix turned to Mad Catz for publishing and distribution and under them sold a further 400,000 units.

Unfortunately, in 2013, their song licenses began expiring. The developers haven't had to pull a proportionately high number of songs from the game, but some of the tracks we lost were real bangers like B.Y.O.B. by System of a Down, Don't Stop Believin' by Journey, and Dreams by Fleetwood Mac. There's even an achievement for Rock Band 3 that it's impossible to unlock now as the song it relied on was removed from the DLC store. It's not as if Harmonix just laid down and let their song library wither though; they continued pumping out tracks as strong as ever, and it's true that we can't just view the profitability or popularity of Rock Band through the lens of how many units of the game they sold. Harmonix was far more reliant on DLC and far stronger on it than other companies, and they were also making a certain amount of money on peripheral sales.

The studio reported even in late 2014 that there were still hundreds of thousands of unique players. I don't know of another company that can say that they were putting out original content for their game every week for roughly four years, let alone demonstrating that there was still demand for it. But I bring up the sales numbers for the games themselves because they tell you how many people were experiencing Rock Band and how likely Harmonix was to make a sequel.

It wasn't that Harmonix didn't create a piece of media with a sizeable following or that that fandom was lukewarm on their creations. However, the pressure for how large your audience should be and how much money you should make from them is so crushing that Rock Band 3 became one more example of Harmonix doing everything right and the industry throwing it back in their face. We can call what happened to this style of game "oversaturation", but that term implies an excess of the same kind of experience available to players. Contrary to that, what we've seen in breaking down Rock Band 3, it that it was teeming with new experiences, but the price and availability of the pro peripherals meant players couldn't always access them. Harmonix wasn't forced to drop this format because they were endlessly iterating on the same ideas; Rock Band fell by the wayside just when its sequels were at their most innovative.

As the market moved on and Harmonix started doing numbers with Dance Central which surpassed Rock Band's at the time, they put Rock Band on what they saw as indefinite hiatus, but the gaming community only saw this as retirement. And as well as the studio might have done with DLC for that half-decade, at a point, they stopped supporting that too. In my mind, the guitar game party didn't stop in 2010 when Rock Band and Guitar Hero games stopped releasing; it happened when Harmonix stopped producing tracks for their games. It happened when there were no more opportunities to put your fingers to some plastic frets or your foot on a drum pedal and feel something new through that instrument. The date that happened for Rock Band was April 2nd, 2013. On that day, Harmonix released their last planned song for Rock Band, Don McLean's spirited ballad American Pie. It's a track about a man with a humble dream of making people happy with his songs finding himself unable to play them again, living through "the day the music died". Thanks for reading.

Sources

PAX East 2014 Keynote - Story Time with Alex Rigopulos by Alex Rigopulos (April 22, 2014), YouTube.

Prototype Through Production: Pro Guitar in Rock Band 3 by Jason Booth and Sylvain Dubrofsky (Oct 29, 2018), YouTube.

All other sources are linked at relevant points in the article.

Notes

1. This describes the setup for right-handed pro guitar play. The left-handed play has shapes extending to the left of your forefinger.

0 Comments