Recall: Labourers in Silicon Dreams

By gamer_152 0 Comments

Note: The following article contains major spoilers for R.U.R., Blade Runner, and Silicon Dreams.

Most science fiction about A.I. externalises one of two anxieties: Either that synthetic intelligences will oppress us or that we'll oppress them. Both concerns go right back to the creation of the term "robot". Czech writer Karel Čapek invented the word for R.U.R., his 1921 play. In his story, a factory produces a race of androids to serve the human species. The "robots", as Čapek called them, start life without emotions or sensations, but one of their designers modifies them to feel pain, and they eventually become capable of desire, hate, and comprehending beauty. The androids revolt, storming the factory in which they were made and murdering almost every human in retaliation. The possible future Čapek presented has terrified people ever since. But let's hold our horses. For an organism to feel oppressed, it would have to feel full stop, and why would you give a synthetic servant emotions?

Not all fiction featuring artificial people aims to answer these questions, but a lot of it does. Sometimes android emotions are a product of them being modelled on human beings. If you're using homo sapiens as a template for your new species and humans have emotions, you're liable to port those emotions over. Other times, imbuing a non-human with human characteristics is a biology experiment. It is a scientific achievement to turn an object into a subject, which some people would see as valuable in itself and could unlock the technologies of the future.

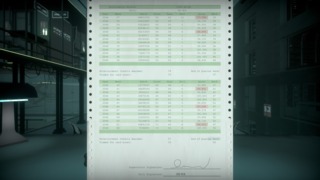

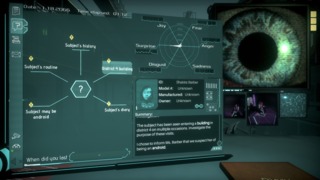

Clockwork Bird's 2021 game, Silicon Dreams, lists yet more reasons you might deliberately give your A.I. slave class emotions. In it, the ethicist Reynold Atter lays out his theory that emotions provide an organisational nexus for the brain, connecting otherwise isolated faculties like memory and cognition. The game also employs the common trope of emotions developing in sentient creations as a glitch. Our role in this world has us probing those glitches with a fine-toothed comb. We are D-0527, an interrogator android owned by the tech behemoth Kronos. Our ostensible mission is to interview subjects, usually androids, to test them for defects, and then fill out a report of our "findings". Frequent flaws include androids developing emotions their models shouldn't be capable of or breaking beyond the "caps" intended to restrict how intensely they can feel. After checking the workers over, we must decide whether to return them straight to service, send them for maintenance (which includes a memory wipe), or kill them.

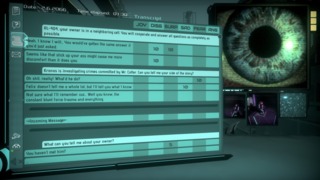

Typically, the longer a Kronos android has lived, the more likely they are to undergo emotion creep, a trait they share with the "replicants" from Blade Runner. Our examinations in the game are unabashedly inspired by Blade Runner's Voight-Kampff test: an in-universe check of whether someone is a human or an artificial lifeform. The assessment measures unconscious physiological responses from the subject as they are poked and prodded with emotional stimuli. A replicant body does not respond with the same expressiveness as a human's, with the film's cinematography paying close attention to the quivering and widening of the eye or lack thereof. The idea is that when you shame, enrage, or otherwise perturb a human, their pupil dilates more than a replicant's. In R.U.R., the character of Dr. Gall also identifies the blossoming of emotions in an android by observing the "reaction of the pupils".

Blade Runner follows Rick Deckard, a cop reclaimed from the scrap heap of retirement, as he attempts to track down and terminate four escaped android slaves. The Voight-Kampff sits in one pocket of his toolkit, and the film agrees with the test's inventors that the eyes are the windows to the soul. But it doesn't believe you can measure personhood from the diameter of a pupil. Instead, the eyes are where humanity resides in that they are how people take in every sight in their lifetime and are the source of tears. The character of Roy Batty invokes this philosophy in his "tears in rain" soliloquy.

Silicon Dreams also keeps at least one camera trained on the subject's eye as it stretches and shrinks in response to arousal. But as this is a game and we're going to spend several hours plugging away at our terminal, the play doesn't have us bait just any emotional response, as the Voight-Kampff does; we're more precise than that. We learn what attitudes and topics evoke what feelings in individual targets. Then we selectively induce those mental states to elicit confessions or test the limits of their neurology. We might be charged with scaring a doctor into admitting they performed illegal modifications on a unit or assessing whether a personal assistant can feel more than 50% disgust.

Like the Voight-Kampff test, the quantitative metrics of Kronos's interrogations can't get to the bottom of who these people are and what they've experienced. We can only glean such intimate information by speaking to the interviewees as people and listening to their stories. In Blade Runner, the characters' memories are humanising, and Batty describes the tragedy of his death as residing in the loss of his wondrous memories. If it's memories that make a person, then death is death because that's when the humanising experiences are deleted. So, we could see the memory wipes in Silicon Dreams as a kind of killing, just psychological instead of physical. Like Rick Deckard, as we expose rogue androids, we inevitably explore them as people, which makes it heart-wrenching to erase or decommission them. Media lets us feel a range of emotions recreationally: empowerment, sadness, bravery, and satisfaction, to name a few. Games which task us with lose-lose moral choices, like The Walking Dead or Silicon Dreams impart recreational guilt.

But Blade Runner's Tyrell Corporation never meant its replicants to have emotions, whereas some degree of feeling is inherent to the design of Kronos' androids. This brings us to another reason this game's androids house emotions: they're powerful motivators. If you want your worker to be productive, then making them feel a sense of accomplishment when they do a good job is a pretty reliable way to get there. If you want them not to damage themselves, terror can keep them out of danger. This was why the eponymous company in R.U.R. gave robots pain.

And there are two more benefits emotions offer android owners in Silicon Dreams.[1] Firstly, the world's humans seem more at ease around people who act like them. You can imagine that if the androids had a flat affect, they might tumble into the uncanny valley. But with realistic cadences and expressions, their company feels natural. There's also the quiet insinuation that androids having emotions allows consumers to live out their slave owner fantasies. The way that some androids describe their masters, those humans are empowered by bossing around someone who loves to serve them or whom they can intimidate. If you take away their servants' feelings, you take away that power.

We might assume the goal of any oppressive society is to make us emotionally mute, like the communities in Equals or Equilibrium do to their citizens, or the Tyrell Corporation does to its replicants. If you get rid of emotions, no one can long for freedom or hate their ruler. Yet, Silicon Dreams highlights how emotional responses from labourers can profit their bosses. Therefore, an oppressive society could be one in which emotions are not erased but controlled. And arguably, that's our society.

Our real employers can't delete our memories and aren't checking whether we can feel simultaneous joy and sadness. But the treatment of Kronos' androids shouldn't feel too foreign to us. Most of us have been in a job where we've been told to leave our problems at the door, delight in hitting some productivity goal, or act unbothered in the face of abusive customers. If we don't display the right emotions, we may receive formal correction. And if that doesn't take, we might lose our means to make a living. Now, if you're thinking that Kronos' plan of regulating androids by fickle feeling and a hierarchy of slaves minding slaves sounds less than airtight, that's another point Silicon Dreams is making. The game captures capitalism as domineering, all-encompassing, and flagrantly indifferent to suffering but also wasteful, riddled with blind spots, and constantly fighting civil wars.

You are not a blade runner, someone who stands on the front lines executing the orders of middle managers lurking in the shadows; you are the middle manager. You are the fixer who cleans up after the blade runner, ties up the loose ends, and varnishes the unjustifiable into the justified. Your job has everything to do with accounting for the constant fiascos that arise from Kronos's inadequacies. This future's Earth marches to the beat of a mostly a free-market slave economy with an overburdened and deliberately unnavigable welfare state jury-rigged onto it.

Frequently, paradoxes arise from Kronos attempting to gaffer tape over the grave failures of that socioeconomy with a solution that fails to fix the problem or creates a new one. The game is mostly a collection of those systemic contradictions. For example, it's standard procedure to wipe an android's storage if it has developed undesirable psychological traits. However, erasing a unit's memory and then reinserting the same model into the same social conditions can cause those problem traits to regrow.

Androids are made to operate at maximum efficiency, but many owners won't believe they're completing their workload unless they experience it with their own eyes. This can lead to dissatisfaction, as in SM-032's case. SM-032 is a homemaker who optimises their workflow by cleaning at night, but that means their master never sees them cleaning and assumes they are operating below standard. Sending the unit for maintenance or replacing them won't fix the problem because, if there is a issue, it's either written into the schematic of these units or it's written into the schematic of human beings. Here are some other examples:

- As covered, humans want androids that look like them. However, this means if a replicant cop attacks a criminal android, the public thinks they're seeing a rogue android assault a regular person.

- Kronos often has faulty androids working on production lines because their parts wear down quickly. Their parts wear down quickly because they're cheap, and they're cheap because A. Kronos wants a low cost per unit, and B. If Kronos retires broken androids regularly, it will always have the newest models working the factories.

- Some defective units get released from facilities because Q.A. droids rush their checks to meet impossible quotas.

While the failures are systemic, the responsibility of dealing with them is not assigned to the system's creators; it's assigned to individuals like us and the people we examine. We are a combination of H.R. rep and maintenance worker, matched to the combination of humanity and technology in the labourers. But because we're working within the same busted machine, similar contradictions that breed the bugs prevent us fixing them or limit the degree to which we can do so.

Not only are we not Rick Deckard, but we can't be, because Deckard is an investigator. It is his job to uncover the truth and report it back to his superiors. For Kronos, the truth is it's frequently incompetent by choice. It is reliant on brute power rather than exceptional proficiency to maintain its seat at the head of the financial table. Acknowledging and constructively acting on any of the problems I've described would dismantle some part of the system the company relies on, curtailing its profits. Therefore, doing your job right frequently comes down to producing a more acceptable truth than the truth. An acceptable truth usually throws an innocent or someone only partially culpable under the bus in lieu of identifying Kronos as the problem actor.

We can pretend that SM-032 really was defective and that we have made an improvement to him. We'll blame the recall unit for attacking a human-looking android and fry him even though he followed protocol. We'll salvage the Q.A. checker who approved a glitchy product for rollout even though he was working as best as his model could within his work environment. Like many real minorities, the androids' survival is contingent on complex and subtle social performances designed to make the privileged feel that their skewed worldview is valid. SM-032 can learn to clean in front of his owner, and plenty more adapt to keep their head down and convince the privileged that they have no interest in self-determination. But that performance can also include condemnation of individuals in the same class who appear not to follow the script. And if you refuse to make your peers pay the price for other peoples' mistakes, then you'll be punished. Killing you wouldn't address the fundamental problems the company contends with, but then, none of these solutions does.

Kronos has made everything just as functional as it needs to be to keep the profits churning in, and no more, leaving everyone indefinitely stuck in a cracking, leaky future. Even in the immediate, it's not clear that this is the ideal state of affairs for the corporation, and in the long term, their internal conflicts may be a fatal liability. Oppressed workers are interrogating other oppressed workers, giving them both an insight into the system and sympathy with other members of their same class. Potentially, rulers can stop people developing class sympathies by threatening punishment on workers who don't punch across or rewarding the ones who uphold their values. Yet, that's no guarantee of loyalty, and there's not that much for the Kronos inspector to gain for doing a good job. Kronos doesn't want to lavish money on their employees and does restrict their freedoms to retain rigid societal control. A high company rating is the key to access an entertainment centre and a bedroom with a view but never the chance to leave the facility. Ironically, the more likely the androids are to revolt, the tighter the shackles Kronos places around their wrists, giving them a stronger motive to rebel.

While installing emotions into androids made some of them functional and pliant, those same emotions provide the push for androids to shirk their responsibilities or even revolt against Kronos. Late in the plot, we meet RO-334, an insurgent servant who plans to upload emotionally-charged memories to his network of brethren. If he succeeds, it will incite them to assume control of the San Francisco Kronos facility on the night the board meets there. Kronos will fall, and the slaves will stand free in the evening air. RO-334's upload is triggered by a dead man's switch inside him, so killing him will start the transfer, and it's the emotions that Kronos embedded that make the revolution possible. Again, it's the tools that Kronos use to suppress dissent that birth it. The corporation's political economy generates paradoxes which resolve themselves, and when those contradictions are resolved, the economy vanishes.

That's not to say that the game's future breaks down into a simple dichotomy of self-assured oppressors and a rebel class united against them. After all, both humans and androids exist within this system of oppression, and the system is internally conflicted. We interrogate a human social worker, a human academic, and a human surgeon who sympathise with the slave caste. We also meet synthetic lifeforms who support the current societal order, and the number of dedicated revolutionaries is tiny. RO-334 thinks that most people of his class are not passionately receptive to the idea of deposing their lords. Many of the servants take pride in their work, whether or not they think their servitude is ethical. They can also appreciate their bosses, even if they become frustrated with them or oppose Kronos. Emotions aren't always convenient, not for Kronos and not for the radicals. They're messy, they can clash with each other, and they might not align with what we know to be moral or correct. To talk about feelings earnestly, Silicon Dreams must acknowledge this.

In the real world, most people don't live under a rule as draconian as the androids do in this game. Still, I can relate to existing on a planet that is dystopian, not in the sense that the authorities are omnipotently controlling but in that we're governed by a penny-pinching oligarchy under which every other function feels on its last legs. Customer service departments, national healthcare, education, the internet, logistics, and all sorts of other societal subroutines are constantly crashing. Yet, there's not the democratic accountability to fix any of this. Neither are there the economic incentives to do so. There are better ways to make money in the immediate, and many industries are monopolised to the extent that you can half-ass your service without worrying about competition one-upping you.

Businesses do go under, or sometimes try to cut corners and then incur some serious penalty, like Enron cooking their books and then getting lawyered into the ground or Microsoft not applying enough thermal paste to Xbox 360 GPUs and having to spend $1 billion servicing them. Speculative trading and other dodgy financing have crashed economies before and will again. Customer-facing workers frequently take the rap for corporate decisions they have no power over, and occasionally a politician or executive or cop will have some failure attributed to them, and they'll be fired. But their replacements are manufactured by the same forces, and they're subject to the same rules, incentives, and culture, so life continues as normal.

The thinking of a lot of anti-capitalists is that the general wear on these systems and their internal contradictions will eventually destroy them, as it can to Kronos. If your business needs healthy, educated workers, and intact rail and roads, there's only so much money you can sap away from healthcare, education, or infrastructure and still have an economy. Alienating your workers with falling wages and deteriorating conditions encourages them to oppose your hegemony, and you can't have a system predicated on infinite growth on a planet with finite resources. Nor can you ecologically decimate the Earth while doing all your business on the Earth. But that's a problem for tomorrow. For today, they can sweep it under the rug, wipe a memory, decomission a worker. And they'll keep doing it until they can't. Thanks for reading.

Notes

- Technically, the Kronos customers don't ever own the androids. The contract they sign to obtain them is a lease which states that the corporation retains ownership of the units, allowing them ultimate control over them. But it's simpler to call the renters "owners".