Star Stuff: The Pleasant Surprises of Katamari Damacy

By gamer_152 3 Comments

Many video games live double lives. In one, they are a series of systems and levels that aim to provide the most fulfilling and fascinating interactions. In the other, they attempt to present objects and characters that adhere to real-world principles. One of the most common conflicts you see in video games is that they can't rectify that identity crisis. By attempting to pursue one of those personalities, they compromise the other.

A game may play a cutscene in which the world is on the brink of collapse and the protagonist promises to spare no sacrifice to save it. Then, playing as that protagonist, we hesitate to save it as much as possible, instead spending our time squeezing into the corners of levels, searching for collectables. A simulation might cast us in what looks like an accurate storming of the beaches of Normandy. However, it needs us to resupply as conveniently as possible, so we also vacuum guns up from the sand wherever they sit. Games are replete with these clashes between expectation and reality. However, the developer's job is not always to reconcile the realism of the game's setting with that of its play. Keita Takahashi's Katamari Damacy is one of the brightest examples that embracing that clash, rather than resolving it, can lead to delightfully disorienting experiences.

If you're a little rusty on your Katamari, it goes like this: One night, the King of All Cosmos gets drunk and inadvertently destroys all the stars in the sky. We play as the Prince of All Cosmos, who must tack together some replacement celestial bodies. We do that by taking a vast sticky sphere: a "katamari", and rolling it around the homes and towns of Earth. As we send it on its merry way, it affixes objects to itself, becoming a big beautiful ball of junk. The bigger the katamari, the larger the cargo we can adhere to it. However, if we knock it into anything bigger than it, items will shake loose from the sphere. Each level has a target size for the katamari, which we must reach before the timer runs out.

Katamari Damacy is full of ideas and occurrences that don't make sense. We push a huge glue ball around the planet to forge a star. The environment often contains characters who behave inexplicably: animals driving shoes and martial artists somersaulting down roads. The stuff of fantasy is commonplace on this Earth: there are elephants in the big city and mermaids in the lakes. All these sights and slights of logic imbue the game with a surreal comedic tone. In pursuing that tone, Katamari makes its break from the sensible a strength rather than a weakness. Surrealist art understands that stepping outside of what's possible in the material world brings the entertainment of the unexpected.

Surrealist humour is a rich vein because jokes frequently rely on the sudden reveal of an element that we did not anticipate finding in proximity to another element, and so does surrealism. There's the joke, "There are two fish in a tank, one turns to the other and asks, 'Do you know how to drive this thing?'". Or perhaps you'd prefer the comedian Jake Lambert's gag: "A cowboy asked me if I could help him round up 18 cows. I said, 'Yes, of course. – That's 20 cows'". The humour in these and other jokes arises in the reveal of the peculiar detail: the fish tank actually being a military tank, the "round up" not being the corralling of cattle and actually being the arithmetic kind of rounding up. These jokes become funny at the point that the mundane becomes juxtaposed with the absurd, which is also the idea behind surrealism. Clocks have the texture of wet meat, lobsters sit on rotary phones, an apple replaces a man's face, etc.

Katamari Damacy further marries the everyday to the odd by giving us a core mechanic that we can use to interact with any object in an absurd way. Animals, buildings, food, and toys can be rolled into our spherical sculpture and entered into the game's massive encyclopaedia. Because the metric of success in Katamari's challenges is the mass of our rubbish ball, and all objects, by definition, have mass, the developers can include any item imaginable in the play. You are the Prince of All Cosmos, and the contents of the universe are your rightful inheritance. Most video games are relatively focused in their subject matter: they're about motorway infrastructure, a cyberpunk future, feudal Japan, etc. The subject matter of Katamari Damacy, on the other hand, is everything.

The type of empowerment we experience in this Namco game is, however, more precisely defined. We can categorise empowerment fantasy games by the flavours of agency that they offer. Ikaruga gives us firepower, Europa Universalis lends us a long political reach, Zen Pinball plays off our sharp reflexes. Katamari Damacy empowers us by making us feel big, literally. When games leave us awestruck by the scale of something, it's usually something external to us: cliff faces rising up either side of us in RiME or the miles of city we can travel in Driver.

In Katamari Damacy, it's our avatar that creates the stunning sensory overload of the enormous. The game's levels start by establishing a base normal scale and then letting us expand our globe's size and our perspective far above it. Over the course of a stage, we can grow from the size of an ant to the size of a cat. We can start with the same volume as a milk crate and finish as tall as a house. It's almost the same empowerment that bodybuilders are after; get ripped in ten minutes with this one sticky ball.

The game rams home the weight of a large katamari by making it slow as it grows, and the tank controls effectively convey the impression that the ball dwarfs The Prince. Moving in other games is often a case of pushing a single control stick around; you could do it with one hand tied behind your back. But in Katamari Damacy, it takes two digits to get rolling. When you're using your left and right thumb to urge the sphere forwards, it feels like you're a mite of a man, putting your whole weight into shifting a boulder.

Size plays a role not just in the player's fulfilment and in the game feel but also in the relationships between the characters. The King of All Cosmos is God. It's not even really a metaphor; that's just what you call someone who oversees the entire universe. While we've looked at the more famous themes in Katamari's humour: the surreal and upbeat, there's also a dark and interpersonal joke here. The game imagines the crushing expectations that would fall on the son of God.

While some entertainment software pairs us with allies that have a stake in our success, the medium rarely deputises a singular character to judge whether we pass or fail. Doing so could jeopardise our sense of agency. It is also the case that computer game characters invested in our goals are usually congratulatory and encouraging. The King of All Cosmos deviates from these rules: he is an arbiter of our success and not a benevolent one. Our Dad will make comments about our progress and achievements that lean toward the derogatory, and part-way through a level, his highness will remind us that we have a long way to go to reach our goal. Even when we clear the bar, he'll often be unimpressed unless we totally knock it out of the park. His opinion is that the prince of the universe should do more than just the requisite minimum.

This monarch does not hold himself to the same standard. He destroyed entire constellations out of sheer carelessness and is equally as neglectful as a father, losing presents for the Prince or telling him it's boring to watch him work. The King's swollen ego and how small the Prince appears in his eyes are symbolised through the literal statures of the characters. In the scenes before and after levels, we see that the Prince can fit on a single one of the King's fingertips. There's something about Katamari Damacy that reads like a silly version of The Myth of Sisyphus: the Ancient Greek legend about a man condemned to forever roll a rock up a hill, never quite being able to reach the top. But while the King is demanding, he's not implacable. Hit the goal fast enough on a level, and he'll wax lyrical about your speed. Grow the katamari to a wide enough diameter, and he'll be almost moved to tears by your work. In this myth, Sisyphus can reach the peak.

The Prince is miniature, but working hard, he can construct something larger than himself: a massive conglomerate of tiny accolades that can exist on the same gargantuan scale as his father. The game doesn't have much respect for the King's parenting style: it depicts him as comically cruel. But Katamari still coaches us to better form by having us seek his praise. It's an atypical flavour of in-game reward: not unlocks or leaderboard ranks, but parental approval.

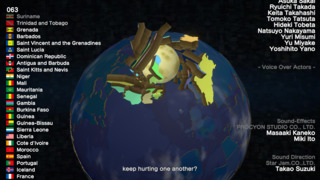

In Katamari Damacy, the katamari is the great unifier. It is a single object that can exist as any combination of objects and people. As it binds together Earthly entities, it can also bond a son overburdened with responsibility and his distant father. The game's credits are accompanied by a tongue-in-cheek inspirational anthem that laments that humans are so divided and calls for us to stand shoulder to shoulder. As the developers' names tick by, we walk the surface of the Earth, rolling as many countries as possible into our sphere like a Pritt Stick Godzilla.

You could see Katamari Damacy as either a goofy celebration of unity or as a humorous satire of worldviews that aim to wrangle everyone and everything into a single mass. The last couple of stages of the game play out like an inverted disaster film where people scream as we adhere their office blocks and islands to our mobile junkyard. We take diverse, functioning homes, towns, and even a planet and destroy them by squishing them into a homogenised lump. And the guy who orders it all? Kind of an asshole.

However you interpret it, Katamari Damacy stands as one of the all-time greatest surrealist games. There's this uncharitable view of the Japanese that they are clownish eccentrics who produce absurd media oblivious to how strange it is. But just like you're not going to get a historic work of fiction by hitting a bunch of random keys on a typewriter, you're not going to create a wonderfully off-kilter piece of media by accident. On the contrary, works like Katamari Damacy show a beautifully honed consciousness of the strange and sublime. Thanks for reading.