NamCompendium 13: Namco’s First Pack of Pac-Man Sequels

By jeffrud 2 Comments

We’ve been on a roll recently here in the NamCompendium, covering some positively mythical games released by Namco in wild hot streak that lasted from 1980 to the end of 1982. Pac-Man, Galaga, Dig Dug, Bosconian, Pole Position, Ms. Pac-Man (if you’re counting games Namco didn’t actually make), and the Rally-X series (if you like crap) all emerged in this period. We’re not even necessarily done with the hits yet, amazingly.

There were some signs, however, that the company was entering a cool down phase. And who could blame them? The actual list of names of people who build and programmed these games is strikingly short, scarcely more than a dozen people, and they had basically spent the last four years forging an electromechanical amusement company into one of the most respected names of a cutting edge industry. There had even been some instances of defying the old “sophomore slump” adage: Toru Iwatani followed Pac-Man with the smash hit Pole Position, and Shigeru Yokoyama (with whom Iwatani had collaborated on Cutie Q) designed Galaga as a perfect followup to Galaxian. That he was then tasked with salvaging Rally-X, with mixed results, might have been the first real sign of things slowing down.

The real key log that would end what could be called the Golden Age of Namco Arcade Games was what to do with Pac-Man. It probably didn’t help that a couple of gaijin who started as bootleggers developed an absolutely sublime sequel to the game. Ms. Pac-Man seemed to come from a place of deep, subliminal understanding of why Pac-Man had succeeded: it drew new demographics of people into arcades with its easy to read iconography and low entry/high skill ceiling design. How better to improve upon it, then, than to simultaneously make it even more appealing to underserved audiences while also increasing the skill ceiling? It was basically all that could be done with the formula to improve it. Midway demonstrated this point by releasing four bastardized Pac-Man would-be sequels over the next two years, and Namco was also about to step in it. Twice, in fact.

Super Pac-Man

August 1982 (ARC, Japan)

I would like to coin a new sort of rule, a NamCompendium Law if you will: the Iwatani Constant. It goes something like this: Neither add nor subtract from Pac-Man’s verbs. Ms. Pac-Man understood this: the titular partner of Pac-Man eats pellets and navigates mazes much like her counterpart, consuming power pellets to harry ghosts and bonus items for extra points. Midway’s less egregious sequels, Pac-Man Plus and Jr. Pac-Man, were also stronger games for adhering more closely to the original design of Namco’s defining work. When they made Pac-Man engage in pinball or administer crappy bar trivia, things got dicey.

I cite the Iwatani Constant here because Super Pac-Man, Namco’s first internal sequel to Pac-Man and arguably their answer to the challenge of Ms. Pac-Man, fiddles with the range of actions allowed by the player and is a worse game as a result.

Things start alright, sure. Pac-Man navigates a maze, uses warp tunnels on the sides as an evasion tactic, eats items in the maze to progress, and uses powerups to assume an alternate form that can lay the smack down on four bloodthirsty ghosts who chase him throughout the aforementioned activities. The essentials are there. It’s what was added that mucks things up. For instance, Pac-Man has gained the ability/verb “eats objects random parts of the maze”. Said unlocks stem from masticating upon keys in the maze, which allow the player access to gated areas full of fruits worth set amount of points. These areas also contain the finite supply of power pellets and a particularly unwelcome addition to the Pac-Man mythos to be discussed shortly.

The other verb is given up on the North American cabinet of this game at the outset: Pac-Man has a button to do a specific action. This should be be a war crime. On both sides of the joystick is a button labelled “Super Speed”. This button does nothing during normal play, but should the player consume one of the Super Pellets made available by opening gates, the player becomes the titular Super Pac-Man. This allows the player to pass through unlocked gates without issue, including the permanent gate to the ghost pen. Players can also pass through ghosts, and eating power pellets in this state extends your time as a giant yellow circle man as well as allowing you to eat the dang ghosts. Finally, that Super Speed button will increase your speed for as long as you are your larger self.

I don’t like this stuff. There’s a host of new game mechanics which must be considered now outside of what Pac-Man does, which is eat things in a maze with a hunter/hunted dynamic between player and ghosts. Now we’re literally fumbling through keys to unlock barriers, unless you’ve unlocked a barrier to a Super Pellet in which case the gates don’t matter and the ghosts don’t really matter, unless you want points, in which case you must also chain a power pellet on top of this and holy shit I don’t care.

On top of this Super gimmick, the ghosts also occasionally pause for a moment for no perceivable reason. There’s also a slot machine, activated by eating one of the objects in the maze, which can yield points. So I guess you also get to scramble to the middle of the field to attempt to hit the jackpot on this thing on top of the actual game? Beyond the fact that the Galaxian ship makes some cameo appearances amidst these objects, most of this just bummed me out.

Oh yes, there are also timed bonus stages every two levels. Take the normal game play, subtract ghosts, jobs a good one. Generously, this sort of solitary Pac-Man experience could be seen as forward looking to games in the Pac-Man Championship Edition lineage, where the ghosts are basically fodder and your main aim is to compete for points against a clock. The CE games have the considerable advantages of not relying on shitty gates and keys, however, and ultimately these levels only increase your score (thereby potentially your life total, and thereby your potential time playing Super Pac-Man).

Arcade-History credits the planning and design of Super Pac-Man to Toru Iwatani, which I find somewhat hard to believe. MobyGames, which tends to provide more comprehensive lists of developers if nothing else, credits Yasunori Yamashita with planning this title. Looking for information on this individual has been one of those great NamCompendium Fruitless Searches that I love so very much. His name is tied to exactly three games on the same source. Individuals who share this name are named as former Presidents of an overseas University of Texas alumni association in Tokyo, and as an auditor for GameOn Co Ltd, an online games company based out of Shibuya, in 2008. The latter Yamashita is also listed as a former Asahi Shinbum employee, which makes his association with the creation of this game (and others, as we shall see) fairly dubious. That, or Yamashita’s singular life path took him from Austin, Texas to one of the finest video game developers of all time, to corporate stooge. A man of mystery.

Fortunately the rest of the names tied to Super Pac-Man are more cut and dry. Toru Ogawa designed the hardware upon which the game was made to run, which was the first Namco board to be based around a Motorola processor (two M6809s) instead of Intel or Zilog parts. A NamCompendium first! Shouichi Fukatani is the listed programmer, and Yuriko Keino composed the music.

I should probably have noted by this point that Keino is the first female Namco employee we have encountered, one who is thankfully still with us today. Her first compositions showed up on the arcade version of Dig Dug, and she would go on to provide music for roughly a decade of Namco titles in the arcades and on the Famicom/NES. Keino blazed a trail within the company that would eventually pave the way for Junko Ozawa (Klonoa, Katamari Damacy) and Kanako Kakino (Ace Combat 3, Taiko no Tatsujin, THE IDOLM@STER), and puts her amongst the ranks of dozens of women in Japan who, while not as ubiquitous as Nobuo Uematsu, have been creating memorable music for decades.

Having said that, this is not her finest hour. The music and soundscape of Super Pac-Man amount to a lightly augmented spin on the original Pac-Man’s ouvre, with the added capabilities an eight-channel custom sound chip over the original’s three channels. I find the atmospheric whooshing noises of the game to be fairly gross, if I’m honest. There’s nothing here remotely as charming as Dig Dug, though we’ll get closer to those heights in the next title.

Release dates range from 11 August (Wikipedia) to sometime in October (Arcade-History, MobyGames), with Namco’s own Dragon Spirit listing September 1982 as the month that Super Pac-Man landed in Japanese arcades. Bally-Midway handled distribution in North America, with December 1982 being a commonly attested release date. It spread out across the United States far enough to make a cameo in the March 1983 film “Joysticks”, which might be my only opportunity to tell you all that Joe Don Baker rules.

The porting history for Super Pac-Man is incredibly sparse. I may not get another shot at mentioning the Sord M5, microcomputer rules be damned, so I’ll take the time to acknowledge the sole official Super Pac-Man port on said platform.

It turns out one way to improve the mediocre experience of playing Super Pac-Man (or Power Pac, as named here) is to make the whole game a bit faster. I know I would certainly rather have somebody beat me with iron rods for four minutes instead of five, given those options. I find the somewhat frantic pacing of this port to marry well with the sort of pointless, random-ish feel of the game itself. I don’t know what keys open which gates, but I find myself worrying less about such things when my aim is fly through this ever-so-slightly condensed maze eating every last bobble in sight. The redrawn sprites are noble efforts (though the colorblind will lament at the pinkish-red and slightly darker pinkish-red ghosts), and the sound design trades in the richer Galaga font for a more blips-and-bloops micro sound. Not bad. Still Super Pac-Man though.

The only other thing to come of Super Pac-Man’s legacy ports-wise was a cancelled Atari 5200 conversion. Noted as cartridge serial number CX5252, this is a fair conversion and I imagine its lack of release had as much to do with the ill fortunes of the 5200 and the North American home console market, as it did my own conviction that the best Super Pac-Man experience is still based on the same dubious game.

From there, we enter the Namco Museum era well on a decade later before Super Pac-Man was seen again. Even then, we’re a bit thin on the ground. Super Pac was set alongside Mappy and Xevious (the latter of which shall, spoilers, be covered in the next post) on Namco Museum Volume 2, but only the North American version. The Japanese release featured Cutie Q in its stead, with Bomb Bee as an obtuse hidden title as a bonus. This makes the Japanese version of NaMuVo2 about a thousand times more interesting, as it is the only time Bomb Bee has ever been distributed digitally in any form. You can pick it up on Japanese PSN for about 600 yen today, once you’ve chosen the Lawson you’d like to use as your Japanese home address anyway.

Super Pac-Man then showed up again with second billing to another vastly superior game, this time on Ms. Pac-Man: Special Color Edition in November 1999. If you must play a portable version of this mediocre game with inferior visuals and sound, here’s one way to do it (the preferred method would be on a Vita or PSP via the PSN version of NaMuVo2).

There followed eight years of probably not one living soul asking for the next great port of this particular title. It would return, however, in the form of Namco Museum Remix (2007) and its North American exclusive followup, Namco Museum Megamix (2010). Between the two, it was packaged as one of the achievement-less on-disk titles included with Namco Museum Virtual Arcade (360, 2008). Most recently, it was slopped in the not-so-great Pac-Man Museum (PS3, 360, Steam; 2014).

Regardless of the format you choose, you’re still guaranteed the same feeling of concern over whether Namco had any good ideas to follow up on OG Pac-Man. Speaking of which…

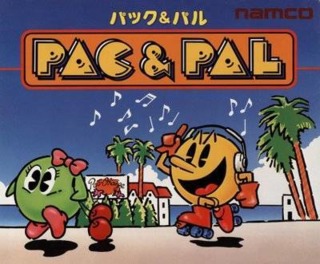

Pac & Pal

June 1983 (Arcade, Japan)

Namco continued to not follow up on the brilliance of OG Pac-Man in the summer of 1983, whereupon they did release Pac & Pal. I do feel that this is ultimately a better game than Super Pac, but at the same time it contains some design decisions that frustrate me more than anything the former did.

Once again, we fundamentally fuck things up from the jump by showing off an attract screen where Pac-Man is now able to “shoot” ghosts by picking up certain sprites in the environment. These range from the Galaxian ship, which produces a Galaga beam-esuqe effect, to the Rally-X car, which emits a smoke beam and also reminds me that Namco has made worse games than this This incapacitates the ghosts, but does not remove them from the field of play. Again: do not change Pac-Man’s verbs.

Pac-Man also contends with the same “fun” gate-opening gameplay found in Super Pac-Man, but here things are mixed up by having the gates opened by passing over cards on the field. I suppose as an attempt to make there feel like some sort of semblance of legible game logic, the object revealed on the flipped cards corresponds to an object on the field whose gates are opened by the act of flipping the cards. In practice, it just feels pedantic because Pac-Man should not be flipping cards or opening gates in the first place. I hate it.

These unwelcome features are dwarfed in comparison to Pac & Pal’s one true Big Idea: an antagonist on the board competing against you. Sure, the ghosts are still here, but they are more of a background irritant compared to Miru, a new character whose sole motivation is to make your life hell. Upon revealing new fruits or objects via the stupid cards, this new character will immediately charge in the direction of said bonus objects and pick them up herself. She will then carry them into the ghost silo in the middle of the screen, whereupon they will be removed from play entirely and thereby robbing you of bonus points. To add to the tension between the player and Miru, there are bonuses associated with ensuring that none of the objects are trashed in this manner during a round. You are thus incentivized to decisively move from activating cards to crossing the maze and picking up fruits, or at worst pursuing Miru and eating the objects out from her grasp as she races to the ghost spawn point.

Miru is a welcome addition to the game, but I feel that the presence of this secondary antagonist would work better in base Pac-Man. That probably comes down to just how much I dislike this whole gate-and-key paradigm, but I think the case is pretty solid. Myriad game guides existed for Pac-Man, which is basically a solved game now nearly four decades hence. Take that formula, with its basically predetermined outcome (expert play notwithstanding) and add an element of random antagonism. What if the player was forced to exit a “perfect” pattern to pursue a fruit? What if Miru stole the dang power pellets right from under your nose? This would be a shift in the “why” component of Pac-Man’s actions, but would not mess with the underlying concepts of eating things and maintaining a back-and-forth with some ghosts. Alas, this hypothetical game does not exist. In its stead, Miru was grafted onto an inferior game and can only elevate it so far as a result.

Pac & Pal runs on the same hardware as Super Pac-Man, with credits to Ogawa and Keino once again. In a fairly soft NamCompendium First, this was the first Pac-Man title developed by Namco to feature full background music throughout. This was also a Keino Yuriko piece. I don’t know if it necessarily matches the action or feels as essential as the Dig Dug music to that game, but the music here is a catchy little fanfare. There’s a nice round bass line beneath it, and if you squint (your ear?) you can almost hear a sort of major key rendition of Bowser’s castle music from Super Mario Bros.

Released in either June (Dragon Spirit credit role) or July (other online sources) 1983, Pac & Pal was intended to be distributed in North America as a tie-in to the contemporary Pac-Man cartoon on ABC. This version, titled Pac-Man & Chomp Chomp, replaced the Miru character with Pac-Man’s in-fiction pet dog as the opportunistic jerk in the maze.

(I would like to give full credit to Brendon Parker, whose research and efforts at PacificArcades.com are the best source of information I have found in English for this title).

PM&CC existed as a handful of conversion kit boards that made it to Europe, and a full cabinet was given a location test by Bally-Midway sometime in late 1983 (MobyGames lists October). However, a confluence of circumstances prevented the game from obtaining wide distribution. Firstly was the rapidly deteriorating relationship between Namco and Bally-Midway, who had been merrily using their newfound company mascot to sell some truly terrible shit. Secondly, by this point in history the much-ballyhooed Great North American Video Games Crash of 1983 was very much in effect. Though video games were by no means dead, the home console market in the United States dried, which did have a knock-on effect in arcades. Thirdly, and this is my own conjecture, PM&CC just isn’t that great.

There’s pretty good evidence to suggest that Namco agreed. Pac & Pal is the first title covered herein since Warp & Warp (July 1981) that didn’t find billing in the Namco Museum series on the PlayStation. It did make a one-off appearance on the Namco History Volume 3 collection for Windows 95 (1998), but otherwise was entirely out of circulation from 1983 to October 2007. It was then bundled onto Namco Museum Remix for the Wii, as well as its NA-exclusive followup Namco Museum Megamix (2010). It was also cast achievement-less upon the physical disk of Namco Museum: Virtual Arcade, and bulks up the incredibly late 360/PS3 digital release of Pac-Man Museum (2014).

Ultimately, I found each of these games to be mediocre titles at best. Super Pac-Man is an evolutionary backwater for the franchise and Pac & Pal is the only thing it sired. The latter is a better game, perhaps, but I find some of the changes more distasteful than anything present in the former. Pac-Man, dear readers, needs to eat ghosts. He should also be spending exactly zero time opening gates with keys, or cards that function like keys. And he shouldn't be touching any Rally-X cars, damn it!

Next time, let’s go ahead and invent the shoot-em-up.

<- Take me back to the NamCompendium