Extra Life Thoughts With Hades

By majormitch 0 Comments

Hey duders! This past weekend I did my part for Extra Life 2019; I’m out of town on the actual game day, so I had to do it a week early. (For anyone interested, my Extra Life page is still up here, and I recorded my stream and uploaded it to YouTube here.) I thought my stream went very well; I for one had a good time and managed to (barely) hit my personal goal. Best of luck to all my Giant Bomb teammates this coming weekend!

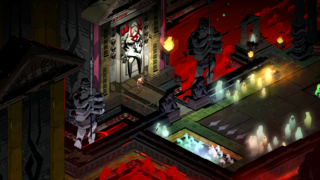

Anyway, the game I played all day, for 16+ hours straight (with some short breaks), was Supergiant Games’ latest, Hades. I’ve really liked all of Supergiant’s games, and really like a lot of their design ethos as a studio. I have been eager to check out Hades for a while, but am also someone who tends to wait until games exit early access to check them out. Extra Life seemed like a good place to just dive in fresh, and see what the game was all about. In short, I ended up liking what I played a lot, and find myself thinking about it and wanting to play more; and this is even as someone who generally doesn’t care for “roguelikes.” As such, I thought I would quickly write up some thoughts from my day of playing Hades: here are four rambly bullet points that stood out to me!

1. Good Game is Good

One of the most important things about Hades is that it immediately feels great to play. I feel like this is a pretty hard requirement for a run-based game that is theoretically intended to be played indefinitely, especially a fast-paced action game like Hades. But right out of the gate moving around and attacking feels great. All your actions are responsive with good feedback, and the enemies themselves are generally very easy to read too. Every now and then the screen got way too busy for me to pick out what was happening, but for the most part the combat in Hades is great. That’s almost more impressive since there are (currently) five playable weapons in Hades, and each one is completely distinct. At the start of a run you pick a weapon, and similar to the different ships in FTL or the different squads in Into the Breach, they offer a completely different starting point. Yet each one feels equally great and equally viable, at least in my experience. It’s hard to overstate the importance of great game feel here.

In addition to just feeling great from a tactile standpoint, Hades feels great in its progression. Different roguelikes offer different ways to make different ones feels worthwhile, and in many ways Hades follows a lot of roguelike traditions. But I think there are a number of smart, subtle things around the edges that help it stay fresher than most. For example, in addition to the different weapons, the game also smartly doles out new mechanics and challenges over time, often in surprising ways. I won’t go into detail at the risk of spoiling (and I seriously doubt I’ve unlocked everything myself), but it almost feels like a traditional single player game at times in the way it introduces new mechanics. There’s a proper learning curve here, rather than just throwing you into the thick of it and banking on the player figuring it all out at once. It’s admittedly a fine line, but I think Hades does a good job at being mechanically deep without overwhelming new players. Stuff like that just makes the game feel even smoother at every moment.

2. It’s Still a Roguelike

All of that said, Hades is still a roguelike (at least in the modern parlance of the word): you go on runs through very similar rooms against very similar enemies over and over, with death being swift and permanent. Each run yields random drops and rewards, and as such not all runs are created equal. This, in short, has been my biggest frustration with roguelikes at large. With the amount of randomness in play, some not insignificant part of your success is going to depend on factors outside of your hands. In Hades, this mostly manifests in two ways. First, the normal way: the drops that influence your character build are random. Hades actually gives you optional perks that, if chosen, help you nudge drop chances towards one build over another, which is nice. And being a skill-based action game, you can in theory beat any run without any additional help at all. But there is still randomness, this is a very challenging game, and more than once I found myself heading down one build path only to not get what I needed to finish it later. One of Hades’ strengths is there sheer number of different, interesting, and hopefully viable ways to build out your abilities during a run. But when you get a string of unlucky drops it makes completing the run that much harder.

The second way Hades’ randomness frustrates me is much more specific, and maybe a little spoilery, so I’ll keep it brief. In the game’s fourth and final area, you have to collect a specific item to advance. You have a choice of five rooms to enter, and the item will randomly be in one of them. And these rooms are among the hardest in the game. So, if you get unlucky and have to go through all five rooms until you find it, your run has become way harder than if you found it in the first room. Yes, you do get more rewards by going through more rooms. But I always prefer it if that risk/reward choice is left to the player, not random chance. I personally think roguelikes are at their best when the player is making interesting choices between compelling trade offs and taking risks, and the more luck you introduce, the more you undermine such interesting choices.

3. Keep It Positive

To rebound from my previous point, one of my favorite things about Hades is that nearly every choice you do make is a positive one. Plenty of other roguelikes and run-based games have done this, especially recently, where you choose between compelling positive options. But it’s still worth noting since a big part of the genre has traditionally involved random events where bad things happen and completely screw you over. To reference FTL again, I remember a lot of events where I had a few options to choose from about how to resolve something, and something very good or something very bad could happen as a result. Worse was that the dialogue options almost never gave any indication whether it would lead to a “good” or a “bad” outcome. So I was choosing blind and regularly getting punished for it. Hades has no outright negative event outcomes, at least not that I encountered. It at worst has neutral ones, and even those you know the result of your choice before you choose it.

How does this play out? Every room in Hades offers a reward. Usually you have a choice of which room to go into, and you get to see what the reward is before you choose the room. And then, once you get the reward, you get a choice within that type of reward. For example, one of the rewards is an upgrade to a boon (these are like your powers, both active and passive). These are always strictly positive upgrades, but you will only get to choose among three random equipped boons to upgrade. So you may not see the one you really want, but upgrades are always good regardless. That leads to a feeling of always getting stronger, and that your choices are about what ways you want to get stronger, rather than hoping things fall your way instead of knocking you back down. This is exciting, and encourages you to be curious and try things out, a process I very much enjoyed from start to finish.

4. Story Time

In the long run, I think Hades lasting contribution to the “roguelike” structure may ultimately be in its narrative trappings. Supergiant’s previous games have all been pretty linear, single player, story-driven games. This is compared to roguelikes which are very divergent and often devoid of any meaningful story. And still, they have found a way to work a story I’m genuinely interested in in Hades, via a lot of smart touches around the edges. First of all, the art, music, and voice acting are all top notch as one would expect from Supergiant. They continue to be an artistic powerhouse, and these touches all imbue so much personality and flavor to the word. More importantly, the writing in particular stands out, as it’s easy to quickly pick up on characters’ personalities and goals from a few well-written lines of dialogue. More than that, they use the writing to explain the game’s run-based structure in a way that makes sense, and enables a larger narrative to unfold. I’m still in the middle of this process, and given the game is still in early access, I can’t say where this ends up. So it might be a bust in the end, but I think they have shown great potential for weaving a through-line story into a run-based game. I’m certainly interested in seeing where it goes, and I’ve been delighted multiple times when I’ve gotten new story reveals and advancements after coming back to the hub after another run. And the characters are all fantastic; a personal favorite is the shopkeeper Charon, who has seemingly endless variants of a groan as his only dialogue. It’s good stuff.

One of my favorite little bits of dialogue is how they reference that the game is still in early access: they refer to this as “underworld renovations are still ongoing.'' These kinds of narrative touches are literally everywhere, and show how much care Supergiant has put into this game already. One of my favorite things about them as a studio is nothing in their games feels like it happens by accident, or goes overlooked. They pay extreme attention to detail, and their games feel very complete and intentional as a result, and full of personality to boot. Even in this early access phase it already feels extremely lively, and I can’t wait to see where it goes from here.

What’s Next?

I want to play more Hades, but in the interest of tackling some more of 2019’s games before GOTY time, I am putting it on hold again for now. But the itch is there; I find myself thinking about what different builds might be like, where the story might go next, and wanting to try out the fifth weapon that I didn’t get to try this past weekend. And it’s cool to know that there are still more updates to come. I will definitely play more of Hades, if nothing else when it gets out of early access, but almost certainly sooner than that. It’s a cool game, and it may end up being the first “roguelike” I’ve played that I get super into. And it was fun to play it for 16+ hours straight for Extra Life. My particular experience was varied and exciting from start to finish, and even ended in the most dramatic way possible: I had my first victory on my final run, just past midnight. Tasting sweet victory at the end was awesome, and only left me wanting to play more.

Anyway, I should stop my ramblings here- thanks for reading!

Log in to comment