Metroid and Me, Part 4: Lone Star

By majormitch 8 Comments

Welcome to part four of “Metroid and Me!” This marks the midpoint of this seven part blog series where I explore why the Metroid franchise has been so resonant and influential for me. If you’re joining for the first time, I recommend beginning with part one and reading these in order. That will get you acquainted with what this series is about, and also get you caught up on the material I’ve covered thus far; links to the previous parts can be found below. Now that you’re up to speed, let’s plow ahead! I’ve spent the previous two parts talking about why I enjoy exploring Metroid’s worlds, but those conversations were more on the aesthetic side of what makes that exploration so meaningful to me. Today I’m going to continue talking about why I love these worlds, but it’s time to shift over to the more mechanical groundwork that props up all that adventure and atmosphere: excellent world design.

| Remix Title: Lone Star | Original Song: Title (Metroid Prime, 2002, GameCube) |

| Remixer(s): Pyro Paper Planes | Original Composer(s): Kenji Yamamoto and Kyoichi Kyuma |

Lone Star

You’ve worked your way deep below the surface. You’ve fought many dangerous creatures, and discovered many powerful new abilities, but you have yet to find your ultimate goal. You head down a new corridor and find what appears to be a dead end for now. You turn another corner, and find a gap you can cross with your newfound grapple beam. Once across you head through a door, and find yourself back in an area you traversed hours earlier. You’ve circled through a path you previously couldn’t reach, and in doing so created a new connection. Better yet, seeing this room again, with more abilities at your disposal, highlights many new possibilities. You set out once more, eager to discover where these new paths may take you.

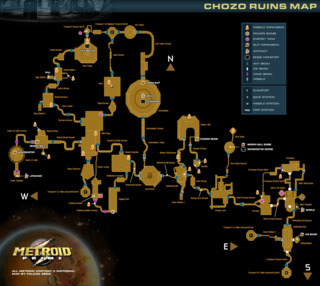

This is but a brief glimpse into the intricate webs spun by the worlds of Metroid. Each one is a carefully constructed network of hallways and corridors, locks and keys, shortcuts and dead ends, all built in service of methodically exploring unknown territory. I’ve already spent a lot of time talking about why I love exploring Metroid’s worlds, with the focus so far being on adventure and atmosphere. If you haven’t picked up on the trend yet, those are two necessary but insufficient reasons for my professed love of these worlds. Simply put, if the actual brick and mortar world built underneath all of that other stuff wasn’t well-designed and fun to explore, the whole thing would come crumbling down. Yet that world design just may be the single best aspect of a good Metroid game, and is also the primary reason Metroid stands atop this style of exploration-focused game. There’s a delicate balance in every corner, with well-considered paths put in place to encourage exploration and curiosity without wasting the player’s time. At their best, these worlds lead to a non-stop chain of poking, prodding, and discovering at a timely, satisfying clip.

The primary way Metroid handles this progression is through a very simple, yet very effective series of locks and keys, commonly called “ability gating.” Whether you need missiles to open a red door, a grappling hook to cross a gap, or the spider ball to crawl across a cavern’s roof, there are many obstacles that can only be passed with certain abilities. This works in the Metroid formula because it allows the game to very clearly and directly communicate to the player where they currently can and cannot go. See a red door? If you have missiles, you’re ready to go here. Otherwise, come back later. Early on this is deftly used to direct the player towards those initial, important items, all without wasting too much time as they’re getting their feet wet. These gates are rarely too far from the main path at this stage, so it quickly becomes apparent when you’re going the wrong way. This also serves to set up the game’s language; Metroid communicates with the player through environmental cues. Ability gates, along with fundamentally good level construction that frequently provide subtle direction, are the most prominent example of this. By setting them up early the game establishes a clear line of communication with the player, all without uttering so much as a word. It may seem overly simple at first, but I’d argue that the best video games communicate with the player in simple, effective ways that don’t interrupt the player’s flow.

As a Metroid game goes on, it continues to expand on the ways it implements these ability gates. Slowly but surely the paths to new gates become longer and more winding, appear farther off the beaten path, or start looping back in on themselves entirely. The different types of gates become more numerous too, and can even begin combining, and keeping track of it all becomes more involved. While the game starts out as a fairly linear path that quickly leads you to some important new abilities, by the end it is a sprawling, interconnected network that has no single, obvious route to your goal. This may sound a bit overwhelming, but Metroid has a well-measured pace to it that expands the world around you in a perfectly manageable way. Just as important, in addition to opening up new areas, each new ability also opens up useful shortcuts back to previous ones. These shortcuts are vital, as they make traversing the map snappier as the game goes on. As I previously mentioned, Metroid is the rare game that does backtracking well; not only does backtracking through each area become easier over time, it also feeds the game’s sense of exploration immeasurably. I previously labored the point that you have to become intimately familiar with every corner of Metroid’s worlds. Structurally, this happens as you acquire new abilities, and wind back and forth between new and old areas. The gaps surrounding the initial trails you blazed are slowly but surely filled in over time, and the result is a fully realized, holistic space. Backtracking is rarely looked at positively in video games, but when it’s used well, it can make exploring a world a much more intimate and complete experience. You get to see every area multiple times from different angles, and you are stronger each time you return. You truly learn and conquer these worlds, and I find that process highly satisfying.

This gets to the heart of what makes Metroid’s world design speak so strongly to me. The large, interconnected nature of these worlds, and the methodical pace you go about opening up every corner of them, embodies a balance of game design that sits in a personal sweet spot. These worlds are neither “linear” nor “open;” they tread a more carefully considered middle ground that avoids the gripes I have with each extreme. If Metroid simply presented you with a linear series of set pieces, puzzles, and encounters, it would be virtually impossible to become invested in these worlds at large. There would be no room for your own self-guided exploration, and if you’ve learned anything by now, you know that exploration is very important to me. Yet Metroid doesn’t open itself up in the way of true “open world” games either. There’s still a highly structured design to its worlds, which lends meaning to its exploration. When you can truly go anywhere and do anything without restriction, none of it is going to feel that important on its own. Metroid’s exploration is thoughtful and purposeful by comparison, without the wasted space or frivolous playgrounds of many open world games. I’ll have more to say on why I want that sense of purpose in future parts, but for now know that it is just as important to me as having room to explore (a desire I’ve already covered in detail).

In other words, Metroid’s worlds allow for more freedom than a linear world would, but they also have more focus than an open one. Your fairly freeform exploration is still guided by more specific challenges and goals, which flow seamlessly from one to the next. In a way, these worlds are big environmental puzzles more than anything else, and ones I love solving. I’ve talked a lot about “ability gates,” but such gates are merely the rules and language for Metroid’s large, exploratory puzzles. They govern how far you can push both forward and back, and allow the game to communicate such limits clearly. It’s a process of analyzing where you’ve been, what you have, and where you can go, which is right up my alley. I’m primarily a logical thinker who likes diving into the thick of things, absorbing details and learning the ins and outs of robust, complex systems. It’s why I chose to study subjects like mathematics, computer science, and analytics in school, and Metroid’s world design holds a similar appeal; it’s all about applying logical rules to complex systems. And yet, while Metroid’s worlds certainly qualify as such systems, they never feel purely mechanical either. Not only can new abilities often be fun and exciting in surprising ways, but there are also plenty of aesthetic pleasures to Metroid’s worlds, which I’ve discussed at length in previous parts. These worlds are not composed solely of raw design and machinery; they feel alive and organic in a way that makes them worth exploring, which is extremely important. Today I’ve discussed the strong mechanical underpinnings needed to sustain it all, which has hopefully brought us full circle in our dissection of what makes these worlds tick. And more importantly to this series, why they connect with me as much as they do.

The worlds of Metroid are large and complex in their layout, but simple and consistent in their rules and language. This design creates a strong foundation, which is built upon with a strong sense of adventure and wonderful atmosphere to create fascinatingly fleshed out worlds that are equally compelling on multiple fronts. There’s room out there for all kinds of video game worlds, and I’ve certainly enjoyed a number of games whose worlds span that spectrum. But Metroid, by combining a variety of traits that speak very strongly to me and my personality, has created my favorite worlds in video games. I firmly believe that the quality of Metroid’s worlds, from the aesthetic to the mechanical, is the single biggest reason for my love of the series, and that’s why I’ve spent these last three parts covering them in their various aspects. I’m sure I’ll have more to say about Metroid’s worlds moving forward, but generally speaking, it’s time to move on to Metroid’s other virtues. Believe it or not, there are indeed other things about Metroid that I love past its worlds, and they too contribute greatly to this series’ personal appeal. So starting next week, I begin discussing Metroid’s broader gameplay design.