Life-Imitating Art: Thoughts on Open-World Life Sims

By Mento 5 Comments

Like many of you, I've been watching Giant Bomb East's Shenmue Endurance Run with rapt attention. I was already somewhat familiar with the game before this run - I've seen LPs of the first and second game, including 2015's SGDQ Shenmue II speedrun, and tried the first for a few hours myself after buying a haul of Dreamcast games off eBay about a decade ago - but seeing the GBEast boys have at it and the type of comments the videos received (it's fun being a moderator), it's clear Shenmue means a lot to a lot of people, in both strongly positive and negative terms.

I won't extrapolate too much on Shenmue's history here. Yu Suzuki's visionary adventure game has such a lofty profile in the video game critical community that countless others have gone deep into the game's lore, the backstory of its development and the influence the game has had in the industry. Throw a dart at any random site that collects or aggregates video game writing, and you'll probably hit an effusive article on the Shenmue series and its importance to the medium. I fall more closely on the "rudderless, dull and bloated" side of the critical equation, and that was before the Endurance Run spent over half an hour staring at Ryo's Timex watch to wait until the story could be continued, but I can at least respect the game's ambition.

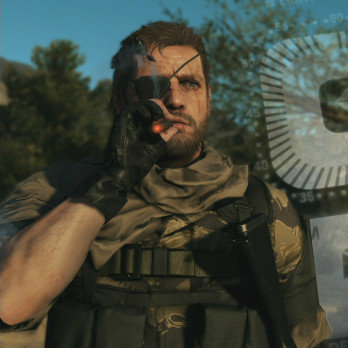

Shenmue's goal, I think is clear, was to create a living breathing world that the player could immerse themselves in whenever the demands of the plot were temporarily at bay. We've seen this in many open-world games before and since, most recently (at least for me) with Metal Gear Solid V. In that game, there are points in the story where the player is expected to "waste time" - though there's a hundred different things you can be doing to improve your character, your base, etc. - before the next story-critical mission kicks into gear, usually as some sort of emergency alert. These lulls in the plot are somewhat deliberate: they're intended to free the player to explore a while, poking into the game's immense amount of optional content that the designer worked hard to include for the sake of verisimilitude, albeit the sort of verisimilitude one often encounters in their day-to-day lives when they have a few hours to spend before a pressing engagement occurs or their workday resumes. We've been conditioned since we were children to find productive (or entertaining) ways to pass the time during these situations, and I feel that's what games like Shenmue are hoping to recreate.

Shenmue, depending on your perspective, succeeds in creating this all-too-frequent real-life scenario, but doesn't quite execute on finding attractive enough distractions to pursue when there's waiting to be done. Training to fight, acquiring new moves and practicing them, is necessary to increase Ryo's skills for when he is forced to fight for real - it's going to be interesting to watch the GBEast crew suffer for their lack of discipline when they'll have the Mad Angels and Chai to deal with - but at the same time is fairly tedious and offers slow, incremental progress with no immediate gains to show for it. Purchasing collectible items you don't strictly need like music cassettes and capsule toys is also a hard sell to the player, so to speak, because they aren't yet certain that they'll need their funds for something more crucial down the road - an uncertainty that becomes all the more pressing once the plot moves to purchasing a means to leave Japan for Hong Kong in the game's second half. Everything else - the mini-games at the Arcade, the vacuous circular conversations with NPCs, the underdeveloped sub-stories with Nozomi and Chibi the Kitten - aren't enticing enough to present worthwhile pursuits when there's a gap in the schedule.

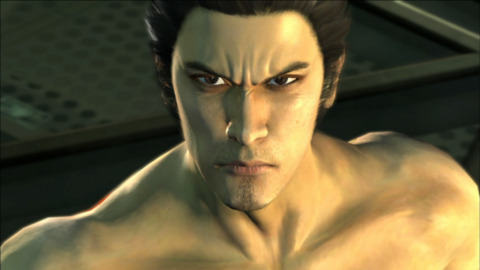

Yet in spite of all this, Shenmue's heart is in the right place, and many other games would take the acclaim and ambition of the game and meaningfully evolve them. In cases like Yakuza, this means streamlining the less story critical "life" elements for side-stories that frequently involve more "substantial" material like mini-games and fighting. The designers of Yakuza, Toshihiro Nagoshi and the team at Sega's Amusement Vision, clearly felt that Shenmue offered a particularly rich vein of video game storytelling where distractions from the plot would in turn enhance it by making the world feel more real and its various secondary and tertiary characters more fully fleshed-out. Yakuza simplifies the adventure game elements - it's always clear exactly where Kazuma Kiryu needs to go, who he must talk to, or who he must throw a couch at - but still offers a huge world to explore and interact with. Each Yakuza game often brings with it a multitude of mini-games from homerun derbies, to Arcade games and claw machines, to darts and pool, to traditional Japanese board games like shogi and mahjong, to various gambling games like blackjack and cee-lo, to even whole golf courses in the third game onwards. Far from suggesting that Yakuza is objectively superior to Shenmue - I think you'll find an equal number of proponents on either side of that debate - Yakuza is one of those cases where a developer sees what another game is doing, and chooses to amplify which aspects they consider vital to the experience while diminishing other aspects considered less worthy. This is entirely to the discretion of the designers, who in turn manage to create a game that better reflects their take on what works in Shenmue and what doesn't, and in doing so creates a game that is more distinctly their own.

Which leads me to another point: That Shenmue being imperfect is one of the most prevalent reasons for its importance as an influencer. If it was perfect right out of the gate, we'd see far too many pale imitations that didn't want to mess around with the game's perfect balance of combat, adventure game intrigue and life-sim "distractions" but couldn't deliver an equally sterling package. Because it isn't perfect, just a compilation of very impressive accomplishments, that allows the developers it influences to take their successive projects in differing directions in order to compensate for or extract what it considers flaws in the original blueprint. Likewise, games could take pieces of Shenmue - using Quick Time Events to punch up their own otherwise non-interactive action cutscenes, for example, or incorporating mini-games as open-world side-activities - without necessarily feeling that they left the choicest cuts on the butcher's block.

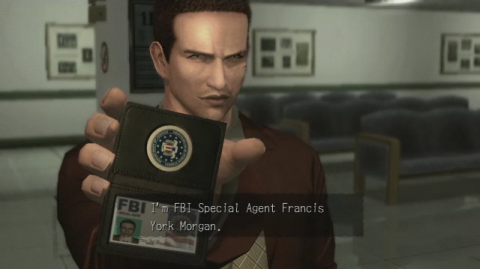

I now move onto another ambitious if flawed project: Swery and Access Games's Deadly Premonition. Disregarding for a moment the game's "Silent Hill" sequences, which features a lot of repetitive combat that the game's developers didn't really intend for the game but were forced to include, Deadly Premonition builds on Shenmue's model in creating a living world filled with NPCs that operate on their own schedules irrespective of the player's influence. This wouldn't be the first game to lift Shenmue's "NPC itinerary" format - both The Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask and Gregory Horror Show made this feature a cornerstone of their gameplay, to the extent that both of them have an in-game NPC schedule timetable that the player can fill out through observing the NPCs in question. However, Deadly Premonition sets itself up as a mystery game first and foremost: the killer is met early and frequently, but everything about them - their motives, their methods, their true identity and the links they have to the town's supernatural history - are left in the shadows. The player, as well as follow each new - though, again, rigorously scheduled - story directive, can spend time getting to know the locals, partake in side-quests and mini-games, or just waste a day following an NPC around - including looking through their windows, if a locked door happens to block their view - to observe any suspicious behavior. The game, like Shenmue, has far more ambition than it knows what to do with but, like Shenmue, manages to turn this flaw into one of the game's most endearing traits.

It's worth keeping in mind that an open-world game with this much consideration put into its NPCs and living world is extraordinarily difficult to pull off: not only in the sense that you're corraling many NPCs, incorporating a huge amount of optional content including different gameplay modes, and tying it all together with a narrative that keeps the player's attention throughout, even with added wrinkle of giving them plenty of reasons to ignore that same narrative for long spells, but juggling all those many aspects to create a collective whole that still has an acceptable level of cohesion and player enjoyment, including for players that will make a beeline for the story events and leave a majority of the game's content in the dust, as GBEast has been doing for Shenmue and the duders did for Deadly Premonition before it. An open-world game with a lot of stuff in it is one thing, and one thing we tend to see a whole lot these days, but one where the world feels real and lived-in and its citizens feel like autonomous beings is a whole different beast. For this reason, I can admire games like Shenmue and Deadly Premonition (and Gregory Horror Show, to a lesser extent) for their emphasis on creating some semblance of a character-focused ensemble narrative in an open-world that lets its many cast members breathe and follow their own agendas, even if I ultimately prefer playing open-world games like Yakuza and Metal Gear Solid V for their emphasis on gameplay and plot.

How about you all? I'm sure I'll get a few Shenmue defenders jumping on this, but to them I ask whaich of Shenmue's many "life sim" elements appeals to them most, and whether they can name other games that follow a similar philosophy. I didn't get into games like Stardew Valley, Harvest Moon, The Sims and Animal Crossing, which perhaps take this "life sim" aspect to a whole new level by not incorporating much of a "story" at all, but they definitely exhibit some similar mechanics regarding NPC schedules and finding stuff to do in your downtime. (I also just kinda didn't want to write any more about Stardew Valley. Feels like that well's as dry as a bone now.)