The SNES Classic Mk. II: Episode XXIII: The Marvelous and Mystical

By Mento 2 Comments

The SNES Classic had a sterling assortment of games from Nintendo's 16-bit star console, but it's hardly all that system has to offer a modern audience. In each installment of this fortnightly feature, I judge two games for their suitability for a Classic successor based on four criteria, with the ultimate goal of assembling another collection of 25 SNES games that not only shine as brightly as those in the first SNES Classic, but have equally stood the test of time. The rules, list of games considered so far, and links to previous episodes can all be found at The SNES Classic Mk II Intro and Contents.

Episode XXIII: The Marvelous and Mystical

The Candidate: Nintendo R&D2's Marvelous: Mouhitotsu no Takarajima

It was to my eternal chagrin that I neglected continuing my playthrough of this delightful SuFami adventure game when I screenshot-LP'd it as an alternative to E3 last year. The first creation of Eiji Aonuma, the present creative lead of The Legend of Zelda franchise, Marvelous could well be seen as a dry run for the intelligent puzzles and subversively humorous tone of subsequent Zelda entries: Aonuma's first as project lead was the divisive Majora's Mask, which if nothing else had boundless creativity when it came to its time-looping puzzles and wacky characters. The presentation of Marvelous is certainly reminiscent of The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past, and deliberately so, but it nonetheless has a very different tone, gameplay model and UI.

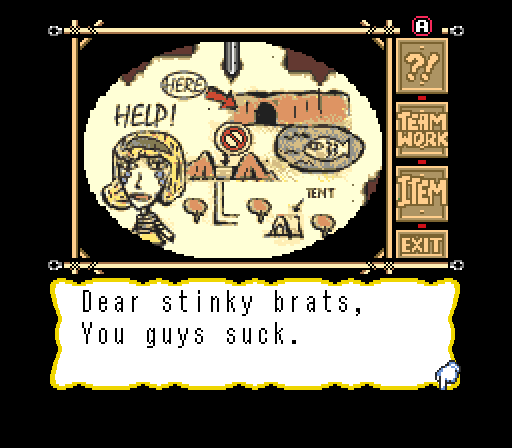

In Marvelous, the player assumes the roles of three scouts on an island adventure, each of whom possesses a specific set of talents a la The Lost Vikings. Dion, the short one in red, is fast and scrappy; Max, the rotund one in green, frequently uses his mass to his advantage; and Jack, the lanky one in blue, tends to be best suited for acrobatics and gadgets. The trio acquire items as the game progresses - comically, those handing out items ask for a specific boy in vague terms like "this item feels suited for the stockier type" - with all three frequently having something to do in any given scenario. With the walkie-talkies, the player can even split the party up and have them pursue goals independently. While the game definitely has its share of combat, the majority of the time is spent solving environmental and inventory puzzles. It's worth paying close attention to your surroundings as a result, as the game's UI frequently has you picking out small details from the environment and using them as pieces of the immediate puzzle. Not quite to the extent of a hidden objects game or the dreaded pixel hunts of older point n' clicks, but very much in that ballpark.

In addition to its superficial resemblance to A Link to the Past, the game feels very influenced by Shigesato Itoi's EarthBound, from its more quotidian tale of a trio of kids on a The Goonies-style adventure involving buried treasure and pirates, to the game's subversive and frequently meta sense of humor. It's never afraid to poke fun at its own shortcomings and those of the genres and series it draws from. Finding a key in the late-game, for instance, gives you a brief Zelda-style victorious music sting while the currently-controlled character holds it above his head, only for the subsequent message to state (and I'm paraphrasing somewhat) "it's not all that exciting, given that you've found a bunch of keys already". That relatively downbeat admission becomes especially true considering the next key is accidentally swallowed by Max, and you have to use an x-ray machine and a magnet to fetch it out of his guts. The game finds levity in the mundane and the clichéd, but is also earnest enough about its sense of adventure, finding the right balance between being too square and being too cynical.

Marvelous is a series of vignettes loosely linked together by a ship that the boys come across which takes them to various islands, each of which contains a very different adventure that results in acquiring one of four color-coded "crystals". These vignettes include one where you travel back and forth in time to right a terrible wrong, infiltrating a pirate fort, visiting a town full of tiny people and helping them deter an ant invasion, and foiling a floral parasite with the ability to clone humans like the pods of The Invasion of the Body Snatchers. Both the story and puzzles alike are endlessly inventive, and you can never be quite sure of what might be coming next. If you ever wanted a crash course on what to expect from the game's first half, that aforementioned LP can be found here in six parts.

Talking of crashing, let's toss a slammer at this tower of a game and see what the P.O.G.S. make of it:

- Preservation: As an in-house Nintendo-developed game, you can expect the presentation to be top-notch. The game uses a higher resolution, which may or may not be awkward for the SNES Classic Mk. II's proprietary emulator, but serves to make the game's pixel art even more detailed. Its adventure game UI takes some getting used to, as does herding all three protagonists around and keeping them out of harm's way, but it starts to feel like second nature before too long. Importantly, the game still has historical value as not only a first-party game with a unique IP, but also a clear indication of the sort of high-concept ideas that Aonuma would eventually integrate into the Zelda franchise and its many iterations. 4.

- Originality: The Zelda comparisons are truly only skin-deep, at least at this stage of Nintendo's second biggest franchise. Marvelous has elements of Zelda's action gameplay but is geared towards puzzle-solving and adventure game challenges first and foremost. It's unlike any other game on the system, taking ideas and visual cues from several instead, and I'm struggling to think of any modern Indie adventure game that's quite as varied in its content. It's an incredibly impressive game, the sort of adventure that could absolutely convince your bosses to hand you the reins to one of their most important franchises, and one of the system's many unfortunate cases of a great game arriving far too late to be considered for localization. 5.

- Gameplay: An awkward UI doesn't spoil some otherwise fantastic gameplay fundamentals and quality-of-life inclusions. You can save anywhere, you can easily summon your friends via walkie-talkie or via a whistle button if they're in earshot, health is plentiful, the game's sole currency is in ample supply if you take the time to observe your surroundings, and there's a built-in hint system for the truly stuck that never gives too much away. While it has a thousand puzzle ideas to toss your way, it doesn't take long to figure out what it wants you to do with any one of them, and the vignette-style progression means that you won't have a huge number of screens to backtrack to if you're looking for a missing item or fork in the road. It can be a bit difficult controlling three characters during a boss fight, as your friends can still be hurt even when you aren't commanding them, but for the most part it plays like a dream. 4.

- Style: Aonuma's penchant for bizarre supporting NPCs and physical comedy are evident as far back as Marvelous, and the game makes use of crude sketches and other cutaways to break up the standard top-down visual style of the game. Your three characters can be expressive at turns, there's a diverse range of character designs and environments, and once you're used to the picture-in-picture UI that isolates the part of the screen you're on and surrounds it with menu options, it's kind of a neat way to take a closer look at the world. However the music's not quite the standout of other first-party SNES franchises, though pleasant enough, and the overarching pirate treasure story isn't nearly as fascinating as the individual stories each vignette provides. 4.

Total: 17.

Other Images:

The Nominee: Squaresoft's Final Fantasy: Mystic Quest

This one's another nostalgia pick from me. While easily the least of the four SNES Final Fantasy games by almost any metric you care to use, to the extent that it shares more in common with the SaGa games than it does the mainline Final Fantasy titles, for us unfortunates living in the European continent it was in fact the only Final Fantasy game to grace our shores until VII came along. The story behind the game is fairly well-established by this point: Noticing the flagging sales of Final Fantasy IV in the United States compared to its gangbusters success at home, Square's executives determined - quite erroneously - that the western market was just not used to playing these games yet and might even be intimidated by their high level of difficulty and complexity. Subsequently, they developed an "entry-level" Final Fantasy RPG that encapsulated the franchise's systems and themes into a rudimentary, easy and compact adventure that would sit outside the core series. At home in Japan, the game was marketed as "Final Fantasy USA", which probably had Japanese audiences wondering why Square temporarily handed off their biggest franchise to Americans and why the Americans - who invented the intensely difficult Wizardry and Ultima games, among others - made it so basic.

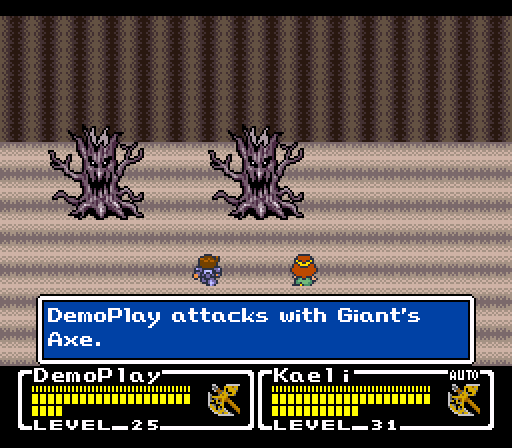

So Mystic Quest was borne from misconceptions and probably a healthy dose of xenophobic condescension. Should that be held against it? Well, in some respects, absolutely. The game has no difficulty to speak of, especially if you're the type of savvy RPG player to latch onto any boon or exploit that might come your way. The high-level claw weapon you acquire close to the end of the game, for instance, inflicts every status effect at once which makes most of the subsequent bosses a breeze (some are even instantly killed by its petrification effect). Magical seeds, which allow you to regenerate all your magic points, can be bought cheap and abused to ensure you always have a stock of the most powerful spells in the game. You can infamously cast the standard Cure spell on the final boss to kill him in two or three rounds, taking advantage of a bug in the fight's coding. The story's so elemental - literally, in the sense that it deals with elements - that it's scarcely worth mentioning; the only time it ever throws you for a loop is when you're tasked with some filler fetch quest out of nowhere. The characters, barring the overconfident thief mercenary Tristam, are boilerplate and uninteresting past their colorful character designs. I'm a fan of the monster portraits and the way they shift, sometimes comedically, to reflect how much damage has been done to them, but they're far too broadly cartoonish to compete with Amano and Nomura's more intricate monster designs in the core Final Fantasy games.

That isn't to say that Mystic Quest is completely without merit, otherwise it wouldn't be here. The game's otherwise deleterious directive of being easy to play carried with it the silver lining of some important quality-of-life changes to the genre. For one, you can see all enemies on the overworld map and they never move. While fighting them was frequently unavoidable - they were often directly in your path, and the game rarely made its corridors more than one character-length wide - you could take all the time in the world to prepare or backtrack to the nearest town for supplies if necessary. If you needed more training, "battlefields" are scattered across the world map, each providing ten battles against level-appropriate foes (provided you conquer them when they first become available) with a reward at the end. You only ever had one other party member to worry about, and their AI could be set to manual or automatic depending on how much you felt the need to coordinate. You don't even have to worry about game overs: every battle lets you retry if you get mowed down by bad luck or poor decisions.

Then there's the soundtrack. If you've been following this feature so far, you know I have a weakness for games with incredible music. There's a lot to be said for music as a lucid source of nostalgia; the feelings we have when listening to some hot jams are more vivid than most any other sensation (beyond chowing down on some madeleines, am I right?) and a big contributing factor to why so-so games like Plok and Equinox have stuck with me over these many years. Suffice it to say, Final Fantasy Mystic Quest has one of the best soundtracks of any Final Fantasy game, even the post-16-bit ones with genuine CD-quality audio. Its mix of typically light woodwind RPG melodies and hard rock percussion gives it a distinct sound that is, frankly, far too good for it. There's nothing in the game's construction that you would remark as innovative, barring the above ways the game smartly patronized its intended audience of dummies, but that high-tempo rock music stands out all the same.

Enough of my alternately bashing and apologizing for this game in the abstract; it's time to put some cold, hard numbers behind those statements and make them concrete enough to work with. Take it away, P.O.G.S.:

- Preservation: Honestly, the game has a really sharp clean look which makes it ageless in a sort of amorphous way, like a face completely smooth of wrinkles, or character, or much of anything. The simplicity of the game and the various quality-of-life additions means it's probably the one SNES RPG no-one could possibly have any trouble with whatsoever, which I might suggest raises its cachet if we think of these mini consoles as a way to indoctrinate our children into liking the same games we did, rather than letting them spend 20 hours a day playing Fortnite and the remaining four practicing the flossing dance. 3.

- Originality: Hah! Well, I'll give it points for the quality-of-life stuff - it's really a huge difference doing away with random encounters - but the game was explicitly built to be "Final Fantasy Jr.". It treads the same narrative avenues, devoid of much in the way of nuance or significant plot twists for the sake of keeping everything nice and simple, and mechanically it could be considered rudimentary even compared to the NES games. I'm afraid it's just not that exciting if you're looking for something distinctive or challenging. 3.

- Gameplay: It's not that the game isn't fun to play, it's just the extreme streamlining process means you never truly leave that early RPG mentality of spending every turn doing normal attacks with the occasional break to heal. Your companion is always predetermined, you have four weapon types to choose from even though you're almost always better off with whichever one you last acquired, if a monster has an elemental weakness it's usually easy to figure out (psst, try fire spells on the ice golem boss), and while there's a few hairy battles early on once you have enough health it's easy enough to heal in time. Its lack of complexity, even for a 16-bit RPG, is easily its biggest detriment. 3.

- Style: Here I go again, back on my five-star soundtrack bullshit. Visually and narratively the game is nothing to write home about (though I will defend those goofy monster sprites to my dying breath) but the soundtrack makes up for that and then some. Just try not to jam along to the boss fight music or the Doom Castle theme, or even Fireburg's jazzy town music. 5.

Total: 14.

Other Images:

2 Comments