Hanmun, Hangul, and Humanism: Why Chinese Characters are a Big Deal in Hate Plus

By Pepsiman 11 Comments

[Author's note: This is an edited reposting of a blog I originally put up on my Tumblr. Given that text has been added and subtracted in some places, those interested in comparing the content can check out the source text here!)

As a longtime writer and even longer-time video game player, it's been interesting to spend these past few years predominantly on the argumentative sidelines watching people hash out the place and importance of language in video games. This discussion has likely existed since practically time immemorial relative to the medium's age; a quick trip to Google's BBS archives, for instance, will tell you just how long people have been debating the written merits of various localizations, particularly ones for Japanese games. But it feels like it's only been relatively recently within the history of games that people have started to tackle more ambiguous aspects of human language and how they affect gameplay experiences. The semantics of lines, the connotations belying a piece of writing, all of the things that we have to infer and read between the lines are all beginning to be evaluated as pieces that also contribute to a game's identity in addition to the old vanguard of gameplay, visuals, sounds, and control. It's a discussion that's especially heated in the realm of feminist issues, but it remains one that's also pervasive in other areas, most notably with regards to immersion and the obligations developers may or may not have relative to their audience's intellectual capabilities.

These are all exciting things for me to watch unfold, as I feel like the more people talk about these issues openly, the less confused games as a whole will ultimately become in trying to marry great game design with great proper writing. One thing that I still don't see manifest often in these sorts of discussions, though, is the grander idea about language and its tie to human culture. It's a really high level topic to be contemplated, to be sure, as it's normally the stuff of linguists, but when discussing what sorts of power words hold over players, I feel it's worth delving into regardless. Words and phrases have power and part of that power comes from belonging to a culture that provides context and substance to the underlying ideas that define them. Being cognizant on an existential level of those effects, I'd personally argue, would go a long way to producing more games with unique, distinct identities, ideally making players more culturally aware of the sorts of existences other people around the world lead. But that's a big step in a time where games are already trying to make big steps in all sorts of directions, so I've been willing to largely shelve those sorts of ambitions while we work everything else out.

Color me pleasantly surprised, then, when I found a game that tackled exactly that in Christine Love's Hate Plus, a visual novel/adventure game-hybrid and sequel to Analogue: A Hate Story, a game I deemed my personal GOTY last year. As an extension of the previous game's premise, Hate Plus tasks you with poring through old logs retrieved from the Mugunghwa, a derelict Korean starship in the far-flung future, in an effort to piece together the events and people that brought about its dramatic social decline. As a game, it's extremely unique to me in that it discusses that fundamental relationship between language, culture, and human identity not within the confines of English or a closely related Romance language, but rather within Korean. One of the bigger, but stealthier underlying causes for social tension within the history of Hate Plus' universe is the place of written Chinese characters, otherwise known natively as hanja/hanmun depending on context, in Korean language, society, and culture. As is the case with loan words and imported writing scripts for most any language, the varying extent of hanja in Korean and other languages over the years has subtle, but profound implications for today's speakers, as well as clearly those in the future. You can't have language without meaning and semantics and when you start importing language from non-native sources, you start importing cultural and philosophical ideas as a matter of consequence. As Hate Plus is keen to point out at times, sometimes these ideas might not be for the good of all people.

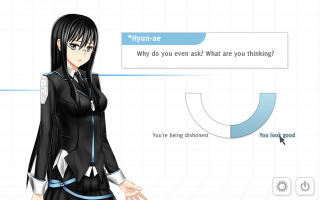

It's complex ground to cover, especially in a game originally released for an audience that isn't likely to know much about Korean, let alone the mechanics of its language. As such, while I feel that Love did a very admirable job trying to make such a dense political and linguistic issue as accessible as possible to non-Korean speakers and, more widely, non-hanja readers, I'd like to try to elucidate a little more for those who don't speak a major Asian language as to why characters like the series' heroine *Hyun-ae find the rise of hanja and hanmun to be such a troubling historical trend aboard the Mugunghwa, especially from a feminist perspective. The things that come to mind for characters such as *Hyun-ae when they think of hanja go far deeper than just conservatism and moral backwardness and it's my sincere hope is that I'll make that logic more clear for those who aren't already blessed/cursed with such literacy.

That being said, before starting, I'd like to point out quickly that while I don't actually speak Korean, I do speak Japanese bilingually. Much more so than Korean today, Japanese continues to make extensive use of hanja within day-to-day living. Given that Chinese is obviously the original source of those characters for both languages, it's not a stretch to say that Japanese people also have ongoing dialogues about the usage and connotations of their equivalent to hanja and hanmun in contemporary society. This includes their use as it applies to sex and gender, too, which is why I feel comfortable talking about this subject at all, even if I lack specific experience with Korean as a language. I also maintain extensive Korean contacts and have familiarity with Korean culture in general, so I'd like to believe that I'm not entering this discussion completely blindly. Regardless, I'm fully aware of how different Japan and Korea remain in terms of language, history, and culture, so if I make any mistakes along the way, you're free to call me out and I'll try to revise my work to reflect the new knowledge.

This is a discussion that will take a lot of preparatory work to get everyone up to speed adequately enough to get to the point where I can discuss these issues as they pan out in Hate Plus specifically. Hanja is one of those topics in foreign languages that makes intuitive sense to people who deal with them already but is otherwise generally impenetrable to outsiders, so my initial goal first is to simply try and evoke the rationale and logic that readers take when encountering them. Doing so will hopefully put patient readers in a decent position to be able to relate to the characters in Hate Plus as I proceed to walk them through what hanja would mean to them in what's supposed to be a post-hanja world. As my infamous essay on Catherine's title screen has probably made apparent, I'm one for long essays and this one definitely won't be any different. So as long as I can keep things relevant every step of the way, I'll consider that a victory in and of itself. Beyond that, I'll note that while I shouldn't need to delve into spoilers for the game, if you're still playing it yourself, there's always a chance I might always undervalue something you haven't chanced upon yet, so if you're concerned about that, hey, feel free to finish it first and come back later if you're still interested in this subject. Finally, it's also worth noting that I'll occasionally be typing out some hanja myself to illustrate various points throughout this piece, so if you don't want to see a whole lot of boxes where Chinese characters should be, it's probably in your best interests to go install your OS' Asian language fonts, which is thankfully easy to do these days. And with that, let's be off into the wonderfully scary world of 漢字!

------

Before diving into hanja as it's specifically depicted within Hate Plus, I feel that it's wise to give an overview of how they operate and are utilized as imported Chinese characters in general. Doing so will hopefully provide a better idea to English-only readers as to their actual utility in modern languages. The best way to do so is to first quickly provide some clarification about how I'll be utilizing certain terms throughout this piece. When I refer to hanja, I'm talking about Chinese characters as they generally exist within the Korean language now. While uncommon, they can be used in tandem with hangul, a much more phonetically-based writing system that most Korean is exclusively composed in today. If you're familiar with Japanese, you can essentially think of it like kanji, which is also mixed in with the phonetic kana scripts in written Japanese to achieve similar effects. Hanja in Korean is a term that can refer purely to the idea of Chinese characters themselves and that's essentially what I'll be invoking when I utilize the word here as well.

One other term that I'll also be using to refer to Chinese characters in Korean, though, is hanmun. The key distinction between hanja and hanmun is that hanmun is a form of Korean writing that relies exclusively on Chinese characters. It's still written using Korean grammar, but otherwise doesn't use hangul and visually resembles actual written Chinese. The core set of imported characters are more or less the same; it's just that there's far more you actually have to memorize in order to be properly literate in using Chinese characters at that level of Korean. In English parlance, hanmun is often referred to as "classical Chinese," which is to say it's not a contemporary use for Chinese characters in Korean today. This initial section will deal solely with hanja since it's designed to get non-Asian language speakers up to speed on how Chinese characters are read and understood in simple terms. Still, that distinction is important to note once I actually dive into the opposition that some characters exhibit in Hate Plus. If the differences still don't make sense now, hopefully they will once I've provided some concrete examples of how they work in action later.

On that note, like with any writing system in today's world, there are some intrinsic tricks to reading hanja that make it possible to be literate with them in spite of the sheer number of them. The biggest factor that makes them decipherable to those who learn them is the fact that hanja characters are all built up what we in the business call "radicals," which are various miniature pieces that come together to make up a whole character. An easy way to think about it might be to compare radicals to building blocks like Legos; individually, one Lego piece doesn't hold a lot of worth or entertainment value, but when you put a lot of them together in a specific way, the charm of building them becomes more apparent and they become a complete, distinct set, a model of something with its own meaning and emotional significance.

Similarly, radicals don't often mean very much or hold power when they're isolated. Some of them operate as their own unique characters and those are highly important to know, but most don't otherwise exist simply on their own. However, when multiple radicals are brought together with other ones and constructed in certain ways, they as a set create an entire character that actually has that unique meaning and significance. They go from innocuous pieces with little utility by themselves to a part of a whole written character that carries linguistic weight. That's the point where hanja can be properly defined in some capacity. The ideas that the radicals themselves can contain tend to be pretty simple in nature, including things such as water, the sun, and more universally abstract ideas, with the actual complexity of many words and characters in part deriving from how those radicals come together.

When studying hanja, you don't have to be actively aware of individual radicals all that much to do well in memorizing and utilizing them. The main point to take away from all this is that radicals give hanja the ability to make their meanings apparent to readers visually. If I see the word 河川 in Japanese, for example, I can come up with the meaning of "river" because a lot of the radicals, such as the three dashes on the left half of the first character, specifically evoke the idea of water in a broader sense. The presence of those core radicals that make up a whole hanja together therefore get associated with the greater meaning of the hanja as a character, making memorization and application of them entirely possible given enough time and practice.

By extension, whole individual hanja characters carry overarching meanings when used in compound words with other hanja. This is important for Asian languages like Chinese and Japanese that still widely use hanja, as it allows writing in those languages to avoid confusion over homonyms and the like; the aesthetic distinctions make it clear when reading them the actual meaning and intent of the writer. Although it's not a comparison that's very often made, English and other European languages actually have similar mechanisms in their writing systems; the presence of phonics, roots, and suffixes is how we can easily determine the exact meaning of individual words in writing, even in case where there are multiple words that sound the same. The specific combinations of Latin characters is one of our techniques for knowing for sure which word is being referred to in every possible situation. "Cereal" and "serial" might be pronounced exactly the same, but it's their spellings that indicate to us whether someone is discussing some type of breakfast food or something that has repeatedly occurred. The same is essentially true for hanja in a broad sense; the complexity and large number of individual characters ensure that the ambiguity is minimized in at least a literal sense. 日, the character for "sun," and 火, the character for "fire," can sometimes be pronounced in exactly the same way in Japanese, but because they look so different just looking at them, it's impossible to mistake what's being meant in writing unless someone just isn't literate in even those basic characters.

The important takeaway from all of this is that full hanja characters like the ones written above come loaded with their own individual meanings and semantics. When they're brought together in tandem to form proper words or compound words, that's when their usage and meaning really become complicated and nuanced. The meanings of words and phrases that take up multiple hanja are as a result fundamentally derived from how a person understands and interprets each character being utilized. A word like 退学, for instance, might mean to "quit/leave school," but that meaning is achieved because 退 on its own indicates "pulling back" or "retreating" and 学 is evocative of "school." Non-native people tend to learn hanja and hanja compounds initially as just raw translations like "quitting school" because memorizing the core meanings of individual characters takes a lot of time. But, a native can understand the word on a more abstract level and derive the idea of dropping out simply because it's exactly those two characters being utilized and they know off-hand what each one means in isolation.

Hanja characters are sensible to those who know them, then, because they're all about visually projecting ideas one chunk at a time, with actual grammar and vocabulary providing the rest of the backbone necessary to turn them into proper language. That projection is powerful, but it also means that certain words and phrases inherently come with social and political baggage. They can combine singular characters and meanings in specifics ways that create loathsome results with far-reaching implications. At times, this has resulted in new words and terms being adopted in an effort to be more politically correct and socially conscious of how languages impact people's lives. To use another Japanese example, an older way to say "wife" is 家内. This is problematic because 家 means "house" or "home" and 内 broadly means "within" or "inside." Even somebody who doesn't speak a lick of Japanese or know a single hanja should be able to intuit why many women now take offense to the term; it's implicitly saying "women belong in the house." Hence, Japanese feminists have largely persuaded people to switch to more gender neutral terms so that contemporary women can be less shackled by the ways they're addressed in society.

People who speak languages that still heavily depend on hanja like Japanese and Chinese grapple with these sorts of problems in meaning and semantics all the time. One of the biggest reasons for this tension is a matter of age; hanja characters were inherited from a very different place in human history, making it a struggle to keep a very old part of those languages up to date within a very different and constantly changing world order, both socially and politically. No matter how much hanja might evolve linguistically within the societies they've been exported to, the reality is that their origins remain deeply Chinese in nature. To condense a very long and complicated history into a few sentences, hanja as we know it wasn't originally designed for mass consumption by ordinary people when it was conceived many hundreds of years ago. It was primarily employed by elite members of society, particularly those within government. This is as true for China as it was for Japan and I would imagine it was the case for Korea as well. Classism and social stratification meant that people who could read and write hanja often led very different lives than those people in other classes who weren't given the right to become literate, or at least to an easy degree.

Knowing that Confucianism has also been a similarly pivotal backbone to Chinese development for an extremely long time, it isn't a stretch to say that hanja characters as they were originally created represented conservative worldviews that only resonated with the people it was ostensibly designed to read by, namely those historical elites. As more people were allowed to learn those characters and became literate, what happened wasn't that the characters dramatically widely changed meanings as they reached mass adoption, but rather those original conservative Confucian ideals imbued within them dispersed to society at large and influenced people's outlooks throughout the generations moving forward. Philosophy and literacy, to an extent, went hand in hand when hanja became ubiquitous, popularizing formally elitist ideas and influencing social development, often at the cost of broad, significant social groups. As issues like the use of 家内 indicate, these are problems that continue well into the current era, a testament to how conjoined hanja characters are to their associated meanings.

It's a pretty safe assumption to say that women have traditionally been one of the biggest targets when it comes to hanja being used to paint people in bad light. So far reaching is hanja's general distate for women that the core character used to express "woman" or "femininity," 女, often plays a critical role in writing negative words. This can effectively state that only women are harbingers of negative things in life and that they either invite bad things upon themselves or bring them to other people. In my own Japanese, for example, this is evident in everything from expressing that you "dislike" or "detest" something (嫌いな) to talking about "rape" (姦する). Contrast this with the character used for "male" and "masculinity," 男, where it's often used for positive actions and good virtues. "Courage" is a prominent example in Japanese, rendered by writing 勇気. *Hyun-ae herself even offers her own example of this bias in composition against women in the original Analogue by way of the adage "Men are honored, women are abased," or 男尊女卑. With that translation in mind, it should be easy to figure out how the second and fourth characters in the original hanja correspond to "honor" and "abasement." All of this isn't to say that there aren't instances where those roles for feminine and masculine characters are reversed, but women come away the definite losers in the positivity department time and again when it comes to words rendered in hanja.

While Confucianism is a philosophy that can and has been liberally interpreted for different causes at times throughout history, it's been far more common to use its core beliefs as a means of restrictively maintaining older social paradigms. Chief among these is the basic hierarchy that has historically informed China and other nations to favor elders above youth and men above women in both the home and society at large. The inability for the meanings of single hanja characters to quickly change and evolve in accordance with current social mores therefore helps enable the perpetuation of such negative interpretations of Confucian philosophy. Alterations of everyday language can therefore be an important strategy in successfully bringing about lasting, widespread social change in places like China and Japan that still use hanja. As I demonstrated earlier, if the roots of the original language used to refer to changing concepts cannot themselves be altered easily, then they must be worked around so that people are simply forced to conceptualize those ideas in a different matter entirely using the phonetic and visual strategies previously discussed. It's a complicated process and while Asian languages are hardly alone in this sort of conflict between semantics and politics, hanja add a unique dimension that complicates the process even further by virtue of their ubiquity.

At this point, it's probably become pretty clear that the squiggles and jagged lines that non-hanja readers take for granted carry a massive amount of symbolic weight for those who can decipher them. It's now possible to really start providing some specific insight into the minds of characters such as *Hyun-ae when they discuss their clear disgust for the existence of hanja in the Korean language. Actually, it may be more accurate to say that they have a disgust for hanja in part because it's largely disappeared from their daily lives as Korean speakers at that point in time. This is based on what's already true for the Korean language today; hanja still maintains a limited presence in Korean society, but it's largely confined to ceremonial roles such as formally writing up a person's name. From my own experience, the youth over there consider knowledge of hanja to be handy in limited situations, but are not otherwise deemed a critical educational asset to have, especially for foreigners learning Korean. For all intents and purposes, hangul is the linguistic name of the game for getting things done on a day-to-day basis, being much simpler to write and, to put it in very fast and loose terms, working like a rough analogue to our own Latin alphabet. Because of these characteristics, hangul places written Korean at exactly the opposite philosophical end of the spectrum compared to Chinese in terms of accessibility and several steps beyond Japanese, which continues to use a hybrid of hanja in tandem with two phonetic scripts of its own to this day.

All of these characteristics help make written Korean feel comparatively liberal in contrast to Chinese and its associated hanja. By opting to write based on a system that revolves around pure phonetics instead of pictographs attached to abstract concepts, written Korean no longer has to pay philosophical and cultural heed to its imported Chinese past in the same ways that other languages still have to. Hangul characters are comparatively innocuous in origin; it's much easier for the Korean language to be able to grow, evolve, and keep up with current trends in the rest of the world because there's no need to linguistically relativize new concepts within decrepit linguistic systems. When a new foreign word crops up that needs to be adopted, it can just be adapted easily into the bubbly hangul and be on its merry way. Chinese and Japanese remain fully capable of adopting new vocabulary, too, but their continued use of hanja subtly affect the dynamics of how those words can interact with the rest of their respective languages. It's not to say that Korean doesn't still run into stumbling blocks where semantics are deemed hurtful to certain groups of people, as much of the vocabulary is still on some level derived from or otherwise influenced by Chinese. The pronunciations of a lot of words haven't gone away simply because hanja has stopped being in vogue. But that devotion to relying on hangul for written communication is still key to granting Korean a unique identity as a language, enabling its speakers to have the power to turn the language into something that better reflects their own society and perspectives on life and the world. They get to use their language on their own terms and can choose to simply not answer to hanja anymore if they deem it unnecessary to remain in the picture, as they mostly already have done.

It's that sense of liberation that fundamentally compel the dissenting characters in Hate Plus to remain wary of a rise of hanja, or more technically hanmun, the all-Chinese character script that resembles proper literary Chinese as we understand it. While social dynamics are hardly perfect in Korea in our time, as well as the various periods *Hyun-ae has endured aboard the Mugunghwa, attempts by government officials on the ship to reinstate hanmun as the major writing script for Korean are seen to be deliberately regressive. As has hopefully been made apparent in the previous paragraphs, the perceived negative effects are substantial and wide-ranging. The most obvious of these effects is believed to be the impact hanmun adoption would have on people in the lower social classes on the ship. The difficulty curve that comes with abandoning hangul as a phonetic script in favor of hanmun neuters many people's prospects at literacy and education, preventing them from interacting with people outside their own socioeconomic sphere of influence. Hangul requires much less sheer memorization to master and had long since proven itself as a replacement that could satisfactorily fulfill the linguistic needs of Korean speakers without the need for complicated pictographs. A move back towards hanmun in that sense is seen as a detriment to a society that could use as many willing and able educated people as it can get to keep the ship viable. A western metaphor for the situation is easy to conjure; simply imagine a government abandoning the Latin alphabet in favor of Chinese exclusively as well and it should be readily understandable just how jarring of a transition it would be for Koreans to make as their exclusive form of writing in that day and age.

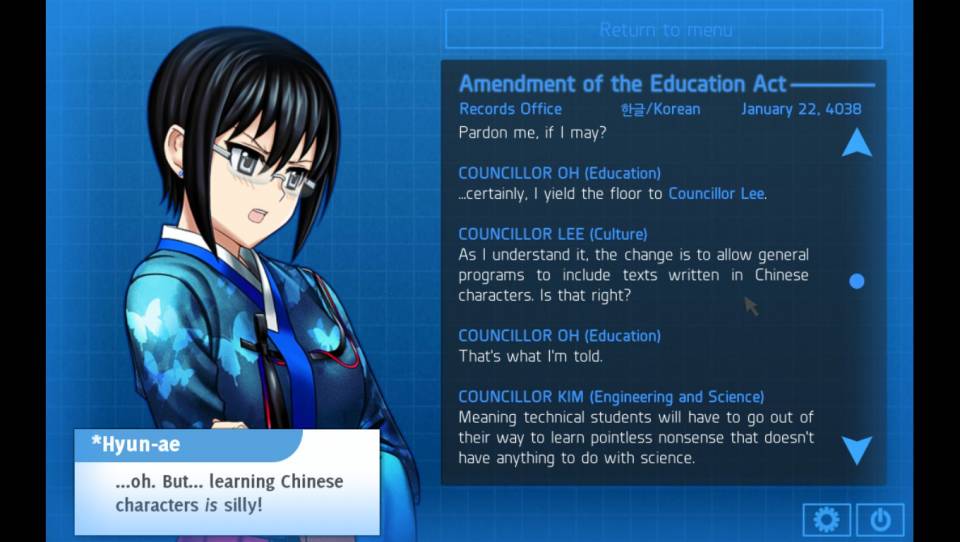

Classist oppression is merely symptomatic of a much greater problem that hanmun embodies in Hate Plus, however. Because of the traditional, old fashioned connotations that are associated with composing in hanmun, liberal-minded Koreans fear that a switch to hanmun means that there is an even greater switch taking place back to conservative social and political paradigms that serve to benefit only an elite few. As I wrote earlier, hanmun/hanji and Confucianism go hand-in-hand because each one developed and proliferated with the help of the other. Again, unlike hangul, it wasn't intrinsically designed to readily adapt to changing thought patterns and social dynamics, meaning it can't readily adhere to contemporary Korean thought. The end goal for the politicians eager to see hanmun reintroduced is, by extension, hardly liberal-minded in nature.

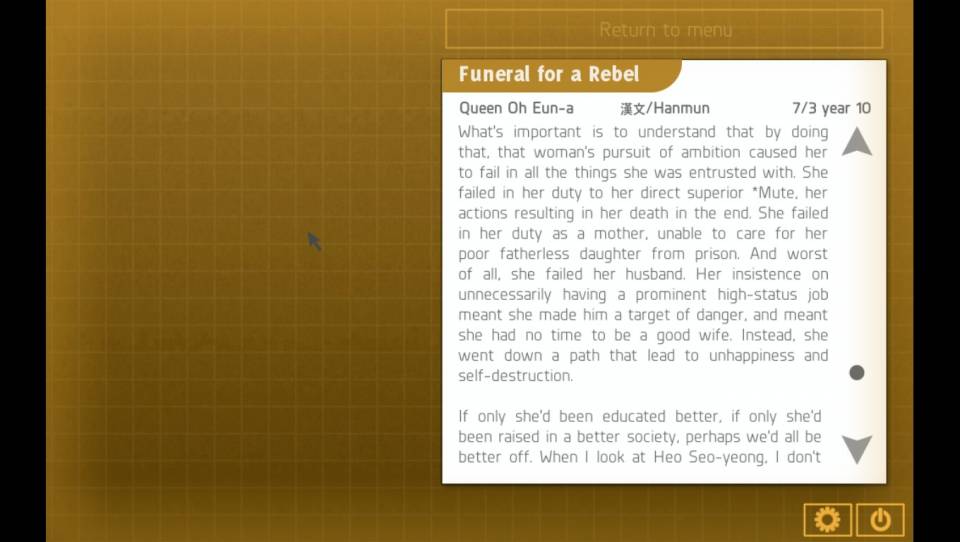

Hanmun can therefore be used as a stepping stone to revive other negative historical traditions that were once thought to be largely excised from Korean society on the Mugunghwa. Indeed, hanmun is brought back into the fold with other political acts like motherhood credits that are designed to make it more immediately profitable for women and their husbands to maintain traditional marriages and start up families than to pursue independent lives and careers. Superficially, this is all argued to be attempts at counteracting birth rate and population problems that the ship is facing, but what they really accomplish is creating the sort of hellish patriarchal society *Hyun-ae finds herself in later on as The Pale Bride in Analogue, the sort where hard-lined advocates of Confucianism thrive. Under such an order, social practices can keep women confined to very specific places and constrict their conduct, while the language embodied within hanmun can meanwhile be utilized to maintain a mentality that reinforces such a traditionally unjust balance. From the viewpoint of hanmun supporters, it'll ideally create a self-fulfilling prophecy where women are both overtly oppressed by society and by themselves by virtue of the linguistic capabilities they'll use to conceptualize themselves and the world around them.

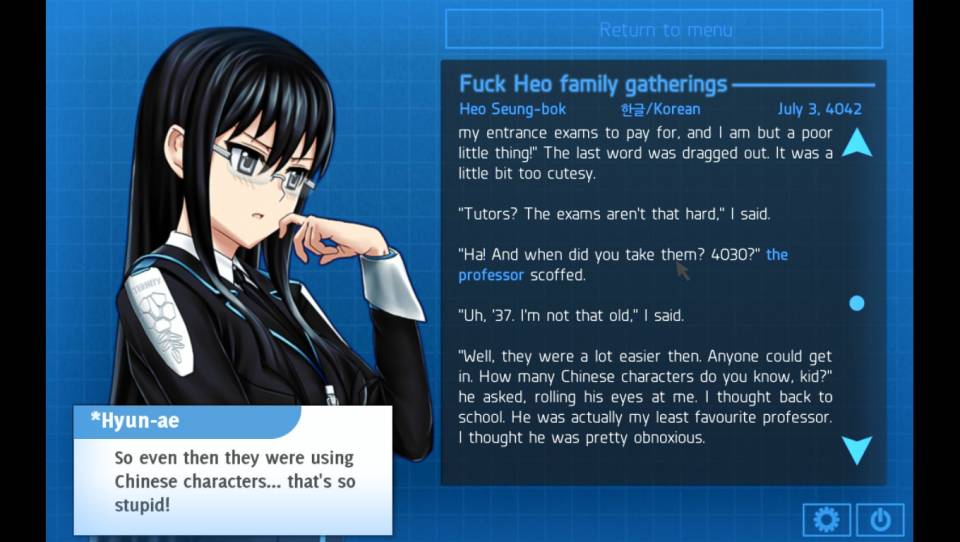

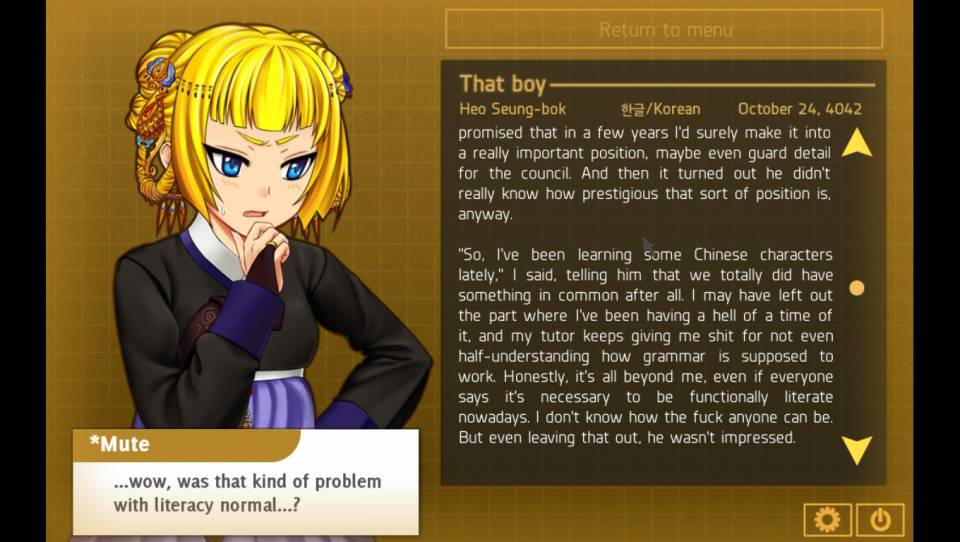

Even for non-hanja/hanmun readers, it's still actually possible to see evidence of all these issues manifesting over the course of normal gameplay in Hate Plus. In the lead up to Year 0, some of the documents in Hate Plus already demonstrate the effects of a return to hanmun occurring as the Mugunghwa is undergoing a major social transition. Careful observers will notice that every message in the game has a classification printed at the top of message windows that states what language and/or script it was originally composed in, consisting of either English, hangul, or hanmun. These designations aren't assigned to the logs and letters without reason; they're subtle indicators of the background and, with regards to the native Korean letters specifically, level of education pertaining to classical writing for the authors. The texts that are originally composed in hanmun are predominantly political and institutional in nature, such as speeches and high level correspondences, limiting the authors to characters within the sphere of politics and higher education. They're therefore not coming from parts of society that commoners would have easy access to on the Mugunghwa, providing a quiet, yet pointed reminder that hanmun is ostensibly not for their consumption. Some characters shift back and forth between hanmun and hangul in the writing, depending on the context and their audience, a move that shrewdly illustrates even more so the gulf in status between those who write only in hangul and those who are also capable of writing in hanmun as well. Only those of the highest status get access to maximum Korean literacy by the standards of the new society being created by the conservative elites.

The reactions that *Hyun-ae, Professor Kim, and others have thusly come from a much deeper place than just an instinctual disdain for the old fashioned and institutionalized. They come from an understanding of a very real past that has existed in both Korea and China, one where ideologies like Confucianism contributed to the creations of societies that inflexibly defined people's roles and artificially determined their alleged "lot" in life, what they could ultimately be good for as contributors to society. For the men in Hate Plus that do actually find themselves concerned about the re-adoption of things like hanmun, they're demonstrably just as worried about the women since it reaffirms a system that's out to pigeonhole them as men in their own extreme ways. They might gain certain "perks" in the process like higher social standing than women, but when considering how men's class status and other arbitrarily designated factors still limit their prospects in other ways, they still would have to deal with their own fair share of existential problems in such a world.

In the eyes of those skeptics, a culture that embraces hanmun also embraces the traditional social dynamics that drove Korean society in that script's heyday, thereby explicitly rejecting modernity and the progress that has been made in giving both women and men true mobility in their lives and the freedom to express their identities in ways that are true to themselves. There is room for beautiful, loving same-sex relationships in a post-hanmun world; but in a time that still accepts hanmun, the Heo Seung-boks, Mimis, Mae Jin-as, and Heo Ae-jeongs of the Mugunghwa have no place, at least not if they want to be themselves. And what of the people that want to lead lives on their own terms regardless of their sexuality? Men who aren't being the domineering breadwinners who think with their crotch all the time aren't upholding their sacred duty to maintaining and progressing the legacy of family lines, while women like *Hyun-ae that have higher ambitions than just getting pregnant and making their husband's household their raison d'être are deemed insolent, whorish, and thoroughly ignorant of the ways of the world and why things need to remain as they are. Society in *Hyun-ae's native time and before the year 0 still isn't completely optimal, but a reemergence of hanmun and their near inability to change meaning, or at least do so in a timely manner, gives people an opportunity to return to old, repressive cultural instincts that were originally driven out at least to some degree for extremely good reasons.

The rocky relationship between hanmun and Mugunghwa society illustrate the irrevocably intertwined relationship that human language and culture possess. The values of one are inevitably mirrored in the other, since it otherwise becomes impossible to communicate in terms that are relevant in the present time. Such principles apply to written languages as much as verbal ones; it's why we have slang and also why older texts become increasingly difficult to read for many natives the earlier they were conceived before the current time period. This makes the current incarnation of a language a massively nebulous reflection upon the world, a statement being made by all the speakers about how they view and approach life and other people. It's evident in everything from vocabulary to even grammatical structures. As *Hyun-ae and the others don't want their world to stall and go backwards on the path of human progress, it becomes instrumental that they actively make strides to block and impede the spread of hanmun back into Mugunghwa's society. Oppression isn't accomplished by just language alone, but words do have power and understanding that is important when waging major social fights, including the sorts depicted in Hate Plus. Mass regression is possible once people lack the means to even articulate in their own minds the potential for things to be different and as Analogue and its referential Joseon dynasty indicate, there's already precedence for it in human history. The Korean language as *Hyun-ae and her fellow opponents speak it has to continue to portray the sort of world they would prefer to inhabit, for once hanmun enters the picture again and is adopted by the people, everybody slowly becomes prisoner to their own culture and their language is the warden with the keys to their cell.

-----

This piece turned out to be a lot longer than I was initially anticipating. As someone who struggled for a long time to competently grasp hanja in Japanese, I come from a not entirely dissimilar background as characters like *Hyun-ae, having grown up in a society that mostly appreciates them from afar. In the case of Japanese, it's just a matter of course that you have to master hanja well enough or else you're just not going to get the most out of that society. Nevertheless, I remain thoroughly empathetic to those who continue to be negatively affected by its history and how prone to stigmatizing it's often been to people, especially women. Reading about the struggles against hanja in Hate Plus made me recall those experiences and reflect upon my own complex relationship with them. I'm not sure how many people will come away from the game actually wanting to know more about where such anti-hanja sentiments come from, but as someone who isn't limited to just one language for verbalizing my feelings, I thought I would try to do my best to make those sentiments comprehensible for those who don't have those same language skills. As I get older and Japanese and hanja become bigger and bigger parts of my day-to-day routine, I feel sometimes that I'm slowly losing touch with how monolingual English speakers approach life, so I'm not entirely certain how much any of this content will resonate with my audience. But if nothing else, I hope it was at least a decent learning exercise in a major aspect of Asian languages that's typically difficult to examine without learning the languages themselves.

My deepest thanks for reading if you've made it this far. As I've mentioned before, any critiques, questions, or what have you are perfectly welcome. I tried to vet some of this content through other Korean speakers, but I know it's still entirely plausible I could have messed up somewhere, so please, by all means, call me out on my mistakes if I've made any!

Log in to comment