I wrote this essay for an English class and I thought it might be an interesting read for people in the always awesome Giantbomb community. Fair warning this post is LONG, English class essay LONG so heads up.

WARNING FULL SPOILERS FOR THE WALKING DEAD

“Septimus thought, and this gradual drawing together of everything to one centre before his eyes, as if some horror had come almost to the surface and was about to burst into flames, terrified him. The world wavered and quivered and threatened to burst into flames”; this fiery vision is how Virginia Woolf chooses to introduce Septimus Warren Smith to the reader in Mrs. Dalloway (15). Were it not for the novel’s previous fourteen pages, one could easily confuse Septimus’s vision for an actual flaming ruin, rather than the tragic imaginings of a shell-shocked war veteran; as a matter of fact, many of Septimus’s passages seem to be in an apocalyptic world all their own. While Woolf sets much of Mrs. Dalloway in a modern and realistic 1920s London, Septimus’s observations seem to draw more from the apocalyptic vocabulary ofRevelations and The Inferno rather than the modern and realistic world that the rest of the novel seems to occupy. This is due to the fact that the Septimus the reader is shown throughoutMrs.Dalloway has passed through the fires of WWI, and he is more than a little addled by the trip; the experience of fighting in WWI drastically alters Septimus’s perception of reality as well as his position in the world. While the popular narrative of the age would dictate that Septimus should return home to a grateful country and a happy wife, his narrative is far more subversive and tragic. Though Septimus is welcomed when he first returns home, his experience in the war irrevocably damages him and leaves him haunted by hallucinations and delusions, yet it leaves him just intelligible enough to wail of the ghosts and unnatural fires he witnesses. The unique way that Woolf positions Septimus in Mrs. Dalloway situates him as an apocalyptic and dangerous character walking the streets of London. Though he seems to be an ordinary citizen, he is a carrier of terrible and possibly infectious knowledge of the cruelty and brutality of modern combat, and of the broken system of patriotism and propaganda which lead him to that combat. It is for this reason that Septimus’s role in Mrs. Dalloway merits comparison to the role of the bitten survivors in Telltale’s The Walking Dead videogame.

Once a human is bitten by a zombie, in The Walking Dead, she/he is immediately changed both physically and metaphorically. The bite is a death sentence that slowly whittles away body and mind until the bitten is converted into a zombie. The metaphorical impact of this transformation on the survivors is similar to that of Septimus’s shell shock on English society: a once ordinary, respectable, and trusted person is now a potential physical threat and a definite social threat to the status quo. Once someone is bitten, life for the survivors can never go back to normal again, just as Septimus’s madness prevents English society from functioning normally. In both cases the infected must be dealt with, and in both cases the solution is the same: the infected person must be eliminated from society. The means and methods of elimination, as well as the difference in narrative medium for the two pieces result in two suicides that have vastly different tonal cues and social implications. The suicide of Lee Everett at the end of the Walking Dead is the conclusion of a redemptive and cathartic journey that leaves the player in a state of despair at the loss of Lee, but an equally strong sense that Lee’s sacrifice was justified and inevitable. Septimus’s suicide, on the other hand, leaves the reader questioning the unavoidability of his death and the societal pressures and misunderstandings drove him to take his own life. Thought the inherent interactivity of The Walking Dead may lead one to presume that the game presents the player with a greater range of interpretive possibilities due to its branching narrative, its ludic elements instead serve to limit and corral the player’s ability to imagine alternate narrative paths for Lee. The Walking Dead provides the player with multiple opportunities to attempt to save Lee; however, the very interactivity of Lee’s decisions lead the player to attempting and failing, resulting in a reluctant acceptance of the inevitability of Lee’s death at the end of the game. While Mrs. Dalloway presents a bleak ending for Septimus, it also presents a host of societal flaws that, if corrected or avoided, could have allowed Septimus to survive. Thus, these two works demonstrate an almost paradoxical issue: a game which has multiple story paths and which provides the player with a wide range of opportunities for exploration actually presents less imaginative and interpretive space for its player than a static novel. Conversely, the static and interactive medium whichMrs. Dalloway employs allows the reader more interpretive room by leaving more potential narrative branches unexplored and unexplorable.

On top of the clear difference in setting between these two works, there is also the matter of the difference in artistic medium each work employs and the role of the reader within those media. Mrs. Dalloway is a novel, and as such, the reader is to a large extent a passive participant in the narrative told throughout. No matter how many times a reader reads Mrs. Dalloway, the narrative will never change: Evans will always be killed in WWI, and Septimus will always feel guilty for his indifference. Though the reader’s interpretation of the events of the novel is subject to change, the text itself is not. However, a videogame is not even a completed work without a player. While a reader is largely a member of an audience, a player is part author and part audience. The player is “writing their own story and exploring their own ideas within the constraints of their art,” and in doing so the player enters into a form of mediated co-authorship of his/her experience (Extra Credits: player). The Walking Dead makes extensive use of player agency and perceived agency to craft its story. In order to talk about the two works in question, the difference in medium, and the resulting difference in experience for the audience, is key to understanding how these two works express their meaning and shape how their audiences perceive their narratives.

As critical analysis of video games is a relatively new endeavor, it will be beneficial to explain some of the terminology that I will use when interpreting The Walking Dead. One of the central concepts that I will use is the divide, or lack thereof, between the ludic elements of the game and its narrative elements. The definition of ludic elements and narrative elements that I will use was derived from an essay by Clint Hocking, “Ludonarrative Dissonance in Bioshock.” The term “ludic element” refers to the elements of the game that are interactive; thus, the ludic elements are the parts of a game that one plays. A game’s shooting controls would be part of its ludic elements, for example, as well as the math behind its combat system, or even Mario’s jump height. In contrast, a game’s narrative elements consist of portions of the game which attempt to convey some sort of story or narrative. These two aspects of videogames are not always separate, and in the most successful games these two elements blend together so thoroughly that analysis of one is impossible without the other. These two elemental categories may seem broad; however, they must be, as games express their meaning in a wide variety of mediums, simultaneously ranging from text, to movies, to songs, to gameplay moments. The combination of the ludic and the narrative is how games derive their meaning and as such I will speak of both.

The Effect of Infection on Society

Each of the main characters in these works suffers from some manner of infection that makes them contagious threats to the society in which they live. For Lee, the infection is a literal infection from a zombie bite, while Septimus suffers from an infectious and crippling worldview brought on by the traumas he experienced fighting in WWI. Each of these infections seems at first glance to be tragic, largely personal, problems which the main characters must attempt to overcome. However, each of these infections in truth generates a cascade of consequences for their respective societies; they each threaten to destroy the established society from the inside. Septimus’s infectious madness and disillusionment are brought about when he is unable to reconcile his war experiences with his post-war life. He finds that he “could not feel:” the war had taught its lessons too well (85). This loss of emotional connection to the world around him transforms him mentally from a war hero to something not unlike one of the bitten survivors in The Walking Dead. Although Septimus is still alive, he is no longer simply an ordinary person; instead, he represents a problem that must be dealt with soon, lest he harm those around him.

In the novel, Septimus presents several layers of danger to himself and those around him. The most obvious of these dangers is the physical danger he poses to himself and those he encounters, as his hallucinations and suicidal thoughts grow more and more frequent. Once he is home in London with Rezia, Septimus begins to argue with her about the merits of suicide; “he would argue with her about killing themselves; and explain how wicked people were… He lay on the sofa and made her hold his hand to prevent him from falling down, down, he cried, into the flames!” (65). It is clear that Septimus is not merely contemplating suicide, but he is so painfully isolated that he wishes to take the one link he has to the world with him. Yet, he is still arguing, not simply acting; although he is clearly paranoid and hallucinating, he is still rational enough to argue and rational enough to express his ideas, and “going home he was perfectly quiet—perfectly reasonable” (65). The greater danger that Septimus poses is to traditional English society, and this threat is brought about by his depression and by the lucidity with which he can describe it. During the war Septimus was a model soldier: he felt “very little and very reasonably” (84). However, his deranged fate runs completely contrary to contemporary images of warriors; rather than happily reintegrating into civilian life when he returns home, he is a nervous wreck. He stands as a living indictment of England’s warrior culture, which is shown throughout the novel by the imperialist Lady Bruton. Septimus’s vivid counterpoint to the popular depictions of soldiers is a threat to all who hold fast to those old narratives. DeMeester also notes Septimus’s potential to overturn the status quo when she writes, “Holmes and Bradshaw encourage Septimus to revise and repress the understanding and knowledge obtained during war. They want him to accept and confirm rather than call into question the socially prescribed notion of warfare” (DeMeester 661). Though DeMeester recognizes that Septimus’s existence challenges popular conceptions of war, she believes that his suicide is ultimately an act of symbolic defiance on the part of Septimus: he is defying the doctor’s attempts to silence him by using his own death to communicate the horrors of war. Septimus’s suicide is not a final act of defiance, but rather an act of conformity. He is conforming to the desires of the society around him. It is for this reason that Septimus thinks that “the whole world was clamoring: Kill yourself, kill yourself, for our sake”; his wife and those around him do not want to be burdened with the truths that he represents and the horrors that he sees (90). They are completely unequipped to deal with the new and complicated vision of warfare and psychological damage that he emblemizes. Thus, it is in the deconstruction of popular narratives and conventions that Septimus is most threatening to English society, and it is for this reason that he is so emotionally isolated. His damaging presence is also why he must be expelled, either through death or quarantine.

Lee’s infection in The Walking Dead similarly undermines the societal structures established in the game. Over the course of the game, Lee and his fellow survivors form a small community; however, the larger societal damage that Lee’s infection causes is the destruction of his parental relationship with Clementine, an eight-year-old girl. This relationship is fostered from the moment that Lee and Clementine meet at the beginning of the game, and it is the driving force behind many of the player’s actions. Clementine is the first character who Lee encounters, and from their meeting Lee and the player are forced into the role of a surrogate father. By the time of Lee’s infection the player has protected, fed, clothed, and trained Clementine to survive in the new apocalyptic world in which she lives. Throughout the game, players forge a bond to the point where many feel that “even in a more dangerous situation, Clementine is always safest with Lee, with the player” (Faces of Death ep.4). Yet, Lee’s infection drastically alters that parental connection; Lee in transformed by a single bite from a guardian and protector to a doomed man incapable of accomplishing the one task that gave his life purpose. In the game’s final moments that player controls Lee as he provides Clementine with an array of possible last instructions, each of which the game tells the player Clementine will remember through a text box on the top of the screen (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6bwUNHTcXlc). Lee’s infection marks the end of an accelerated parental narrative arc for Lee and Clementine which concludes Lee’s redemptive story. The player is given the full experience of guiding a child from innocence to young adulthood in only a few short episodes.

Thus, we can see that though each of these characters suffers from a societally destructive infection, the impacts of those infections are entirely different. Septimus’s infection and suicide is a tool by which Woolf critiques British society, while Lee’s infection is the crescendo of an emotionally draining journey. Yet, each work uses these doomed characters and their tragic plights to show the overarching connections between people in a society. Septimus’s hallucinations unsettle not only his wife, but an entire system of imperialist and militaristic thought. The delusions of a single man are a disquieting reminder of the cost of war and the reader, if not the other characters in the novel, can perceive the damage Septimus’s visions can wreak on popular narratives of war and the people who endorse them. Lee’s death is an example of how even the smallest death amid a calamity is its own tragedy. Though Lee is merely one dying man amid millions, the game provides the player the ability to experience the impact that loss can have by foregrounding the connection between an adult and a child. The player is made to feel both Clementines’ pain at losing a father as well as Lee’s despair that he can no longer help her.

The Cause of Infection

Though it may not appear to be so, both of these infections are not the result of singular traumatic events (the bite and Evans’s death respectively); rather, they are the result of multiple blows to the humanity and psyche of Lee and Septimus. In The Walking Dead, Lee suffers from repeated trauma delivered by moments of sudden and gruesome death which Lee and the player must witness and partake in. By the point in the game where Lee is bitten, the player has forced Lee to do the following: either chop off a man’s leg with an ax or leave him to die, watch as one of their group is mutilated and turned into a food source, bury a dead boy and his dog, and either kill a child or force his father to do so. Unlike in other games where simple button prompts are used during scenes of action or violence, The Walking Dead forces the player to actually aim and control Lee during many of these scenes for painstaking amounts of time; for example, if the player chooses to shoot Duck, a young boy who has been bitten by a zombie, the game places a reticle on the screen which the player must control as Duck slowly wheezes away his last breaths (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vqUzspg9GBg). The act of pulling the trigger is not abstracted away as it would be in so many other games. The developers of the game commented on the emotional effect of this scene in an interview saying,

There’s a lot of people who say “I don’t like this character, I’m not going to feel bad when he goes” and to the extent of “I can’t wait to kill that kid!” But when you actually put a gun in someone’s hand and you’ve said “Kenny, I’ll do it,” a lot of people that I spoke to said “I was ‘no problem, I can handle this’ until the reticule came up and I went ‘whoa, this feels a lot different than I thought it would.’” Or they would shoot, and then walk away saying that, either right before or right after. “I thought I was totally okay doing that, but actually being presented with the reticule and this little sad boy’s face, I thought it would feel like a video game, and I felt not the way I thought I would about that. (Faces of Death ep. 3).

Thus, these ludic elements are not only intended to have a cumulative and negative effect on Lee’s humanity, but also the player’s. This loss of humanity is examined by the Extra Credits team in the video “For Whom the Bell Tolls,” in which they examine the game’s invocation of John Donne’s poem “Devotions Upon Emergent Occasions Meditation XVII” (EC season 6 ep. 5). In this episode they conclude that this reference stands as a microcosm of the game’s message; the game, they argue, is telling the player through the use of the phrase “Ask not for whom the bell tolls” that “each one of us is an incredibly valuable thing. That even the least of us makes the whole more and if we give up on that we give up on being human” (EC season 6 ep. 5). Therefore, although Lee suffers a physical infection at the hand of a zombie, that physical infection is merely the physical representation of a loss of humanity that is occurring constantly throughout game. The true toll of the game is not the death of the body that Lee suffers, but rather the emotional turmoil that the game communicates to the player through Lee.

The team analyzes how the player’s loss of humanity can adversely affect the choices that players make; however, they do not connect this loss of humanity to insanity and mental illness. Yet, this connection is made by the game when the player encounters the Stranger towards the end of episode five. The Stranger is a man whose wife and child are inadvertently killed by Lee’s group of survivors; Lee’s group unknowingly steals their only rations from an unguarded station wagon. This man has clearly gone through similar traumas as Lee and the player have; he says, “I’m not some cannibal Lee. Some killer out in the woods. Some v…villain. I’m just a… dad. I coach little league” (TheAwesomeIncarnate). At first he seems like an ordinary human being with an ordinary background, just another survivor exposed to too much gruesomeness, but otherwise as normal a person as a survivor of the zombie apocalypse can be. Yet, after the Stranger’s death, Lee has the chance to look in a bowling bag which the Stranger has been carrying; Lee finds the man’s wife’s severed and zombified head, to which the Stranger had been talking moments earlier. In this moment the Stranger shifts from a pedestrian questioning Lee’s morality to a lunatic; the tonal shift in this scene is jarring in its rapidity and emphasizes that the long term trauma that one suffers while surrounded by loss can result not just in a philosophical and emotional loss of humanity, but in a full mental breakdown. The developers of the game speak to this emotional and mental degradation when they describe the Stranger as “kind of like an alt-zombie... The world did not turn him into a zombie. It turned him into…The Walking Dead” (Faces of Death ep.5). Also by first allowing the Stranger to question Lee’s and by extension the player’s actions, the player is shown that from a third party’s perspective their own actions can be considered the work of a maniac, a monster. However, by revealing the Stranger to be insane the developers allow the player to invalidate his biting criticisms of Lee’s actions: for how can a man who carries a severed head seriously criticize the brutal actions of another? Thus, the game first chides Lee and the player’s actions as inhuman, and then undermines that accusation by revealing the accuser to be mentally ill and morally corrupt. The player is thereby forced to reflect on their moments of inhumanity before being comforted by the exhibition of a greater sinner; this allows the player to feel the trauma of his/her actions while also confirming that someone in her/his position would likely do much worse.

In Mrs. Dalloway Septimus does not have any sounding-board for his emotional breakdown in the way Lee does; he returns to England with emotions that no one in his society seems to be prepared to permit or tolerate. While the player of The Walking Deadis allowed to see Lee’s humanity through his juxtaposition with an even more depraved survivor, the reader of Mrs. Dalloway is forced to follow the train of thought of Septimus, as he sinks deeper and deeper into madness due to his intense isolation. After his return to England Septimus gradually loses faith in the literature and culture which he had once cherished, “that boy’s business of the intoxication of language—Antony and Cleopatra—had shriveled utterly” (86). Yet, as his inability to feel eats away at who he once was, the world around him insists on turning. Rezia wants children; his boss rewards him with a new position at work with greater responsibility. Septimus is expected to immediately return to his previous life, but when he cannot a doctor is summoned: Dr. Holmes. Rather than recognizing Septimus as ill and in need of help, Holmes instead assures Septimus that “there was nothing whatever the matter” with him (88). Septimus responds to Holmes’s diagnosis by thinking, “so there was no excuse; nothing whatever the matter, except the sin for which human nature had condemned him to death; that he did not feel;” thus, the reader is show that Holmes’s ignorant misdiagnosis of Septimus’s condition acts to further drive him into depression (89). Rather than providing Septimus with a foil in the mold of the Stranger, a more damaged individual who lessens Septimus’s madness through comparison, Woolf instead chooses to isolate Septimus and in doing so accentuate the structural failures in British society that lead to his downfall. While the player is able to see that Lee has been damaged by his trip through the world of The Walking Dead, he/she can also claim a small victory by avoiding the Stranger’s fate. However, the reader of Mrs. Dalloway is forced to stew in Septimus’s mind as the bleak insights that he has gained in combat are rebuffed by the peaceful society in which he lives, forcing him further and further into isolation and madness. Septimus becomes a crazed outlier rather than a victorious survivor.

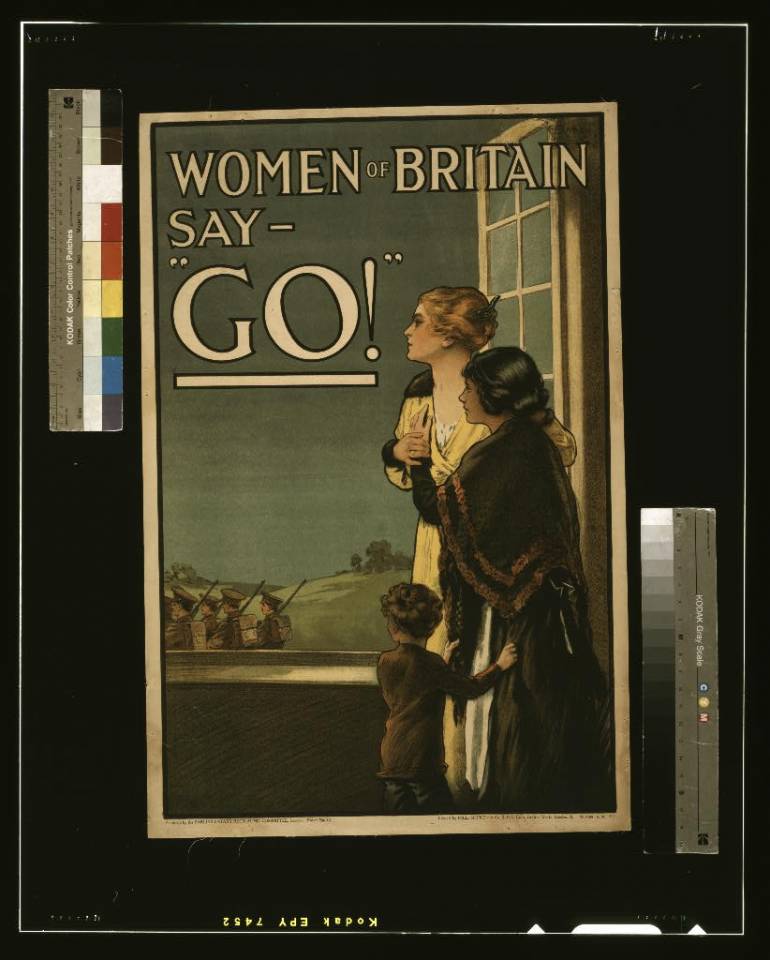

Septimus’s emotional isolation is made all the more disturbing by the fact that his affliction was caused by his submission to nationalist rhetoric produced by English society. Before the war, Septimus was a student and a would-be poet; yet, when war called, “Septimus was one of the first to volunteer” (84). At the outbreak of the war, Septimus is eager to go abroad and defend his country “which consisted almost entirely of Shakespeare’s plays and Miss Isabel Pole in a green dress walking in a square;” through this description of his motivations it is clear that Septimus was not fully prepared for the combat that war required, nor was he well informed of what it was he was actually fighting for (84). Both Shakespeare’s plays and the idea of Miss Pole walking in a square are intangible concepts, ideas floating in Septimus’s head, yet he believes that to defend England is to defend those dreams which he loves and associates with England. Septimus is unable to separate the physical country of England from the symbolic meanings which he has ascribed to it. Yet, this state of misinformation is exactly what England endorsed during wartime; recruiting posters for WWI did not provide well-reasoned and informative articles that argued about the merits of enlisting. Instead, the British government used posters such as this to inspire or shame soldiers into combat.

In this propaganda poster one can see a picture that is not unlike the image of Miss Isabelle Pole that Septimus conjures when he first goes off to war. There is an image of a young woman, presumably a wife, alongside her children looking through an open window at a group of soldiers as they march past; this implies that the women of England are both supporting the soldiers as they go and that they eagerly await the soldier’s return. Furthermore, the face of the woman and the windowsill she is standing in is illuminated by a light source which the soldiers are marching towards; this shows that the soldiers are marching in the direction of the light, not towards death and ruination, but towards some source of truth and justice. This all is reinforced by the text included on the poster, “Women of Britain say- GO!” which is a direct command to men like Septimus to go forth and fight for their country on behalf of their women and their homeland. Septimus is thusly swept up in the rhetoric of his country and willingly enlists in the armed forces. By revealing Septimus’s naiveté, Woolf brings into question the nationalist rhetoric and warrior narratives that are present throughout Britain in the 1920s. She shows the reader how one young man was persuaded to join the army to his own peril and, by revealing this back-story after the reader has already encountered the modern-day Septimus, how that decision ultimately leads to Septimus’s mental breakdown and his transformation from ordinary citizen to infectious threat. She forces the reader to consider the role that Britain’s own war culture played in creating broken men like Septimus, as the makers of The Walking Dead force the player to consider the lasting effects of a world where death is around every corner.

Experiencing the Infection

While Lee’s and Septimus’s infection vectors are key to the understanding and interpretation of their mental and physical slippage, it is also crucial to examine the way that the audience experiences these moments of infection. In the case of these two works, the difference in experience is the difference between riding in the passenger seat of a car careening off a cliff and being behind the wheel, desperately trying to swerve away. In the case of Mrs. Dalloway the reader is made a passenger in Septimus’s mind, forced to travel with him through his time in the army, powerless to stop him from suffering irreparable damage to his psyche. Despite his ill formed rationale, Septimus quickly transforms himself during the War into what his employer “Mr. Brewer desired when he advised football” (84). Septimus is able to grow from a socially marginalized intellectual into the seemingly ideal soldier that society wishes him to be; “he developed manliness; he was promoted; he drew the attention, indeed the affection of his officer” (84). The narrator makes it clear that Septimus’s loss of innocence is societally sanctioned and the manner in which he changes is viewed as additive rather than subtractive. Rather than viewing his innocence as a treasured possession, Septimus revels in its immolation; for how can he become a war hero without toughening his hide? As Septimus continues along the classically imagined path of the soldier he absorbs more and more abuse, yet feels nothing and does not so much as whimper. In her construction of Septimus, Woolf first follows the contemporary image of the soldier; Septimus is a man transformed by war into a more masculine hero. Yet, Woolf almost immediately subverts these expectations when she elects to kill Evans. She writes that, “when Evans was killed, just before the Armistice, in Italy, Septimus, far from showing any emotion or recognizing that here was the end of a friendship, congratulated himself upon feeling very little and very reasonably” (84). Through this description of Evan’s death Woolf conveys that Septimus views this moment as a triumph of his new masculine and battle-hardened persona. Even the death of his closest friend does not draw an emotional pang. Yet, this moment also informs the reader that Septimus does not fully understand the gravity of what he is seeing and experiencing, while the reader is privy to the terror that Evan’s death will later wreak on Septimus. Septimus was “far from… recognizing that here was the end of a friendship;” perhaps the death was too swift to register or one more body among the piles was just another drip in what was a flood of death (84). However, the reader knows that Septimus’s unwillingness or inability to mourn the loss of his friend cannot be healthy. By describing the death of Septimus’s only known friend in such a terse and emotionless way, Woolf makes the reader understand the way Septimus viewed it at the time, and in doing so see how problematic his cavalier attitude towards death is: the very masculine detachment that made him a model soldier also makes him emotionally cold and eventually mentally unbalanced. The narrator goes on to say, “the War had taught him. It was sublime. He had gone through the whole show, friendship, European War, death, had won a promotion, was still under thirty and was bound to survive;” here Septimus’s war history is neatly presented in three sentences, but again there is something askew in the description (84). Van Wert argues that the word sublime denotes “the lesson that human reason can outlast the atrocity of war, forcing the mind to equilibrate incompatible experiences such as death and friendship, war and promotion” (Van Wert77). Woolf, though, is using the word “sublime” to denote Septimus’s dehumanization at the hands of the war rather than his new found knowledge that “ that ecstasies, good and bad, pass” (Van Wert 78). The experience of participating in one of the largest losses of human life in history is being described as “sublime,” denotes a loss of perspective due to the traumas that Septimus suffered during the war. Based on Septimus’s earlier excitement at his newfound masculinity, it would not be surprising for him to also ascribe war sublimity based on the socially acceptable persona he has adopted. It is the loss of perspective and understanding caused by dehumanization that Woolf is asking the reader to see and denounce.

As Septimus absorbs blow after blow the reader is forced to follow him on his journey and question what could have been had Septimus not been pressed into service, had his country better prepared him for the amount of death he witnessed or, perhaps more saliently, had there not been a war at all. In contrast, the player is in direct control of Lee for the vast majority of The Walking Dead. This provides the player with a sense of control and authorship over Lee’s story that is absent in Septimus’s. Therefore, while the audience may consider the various ways Septimus could have been saved from his fate, the audience inThe Walking Dead can attempt to save Lee from an equally unceremonious death. For example, before Lee is actually bitten by a zombie, the player is forced to search for Clementine after she has been kidnapped; the search culminates in Lee approaching a pile of trash, next to which is Clementine’s walkie-talkie. Upon reaching the walkie-talkie, the player is offered a choice between examining the walkie-talkie and examining the trash pile. Regardless of which option the player chooses, Lee is bitten; however, the ludic act of choosing gives the player a false sense of control over the narrative flow of the story (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LmGdFwOw0vo). The player is thus able to see that they, a rational and intelligent human being, were unable to avoid infection and the death sentence therein when given Lee’s circumstances. Lee’s infection is therefore perceived by the audience to unavoidable given his unique situation, as they were literally put in his circumstances and failed to avoid infection. The player is subsequently offered the chance to cut Lee’s arm off in order to slow or halt his death, further allowing the player to act under their own perceived agency and attempt to save Lee (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uwRvwvOA1_A). Yet, at every turn their attempts to prolong Lee’s life are frustrated, forcing them to accept that he is lost. The player has directly and indirectly caused a flawed but ultimately good man to not only lose his humanity but also any hope of a future.

Through the juxtaposition of these two methods of storytelling an interesting effect surfaces: the ludic elements of The Walking Dead actually prompt the player to accept that Lee’s infection and death are unpreventable consequences of his surroundings which are unchangeable, while Woolf’s choice to place the reader in Septimus’s mind as he goes mad and commits suicide prompts the opposite response. Woolf’s writing techniques force the reader to question whether Septimus’s decent into madness could have been avoided had he not fought in the war and had he not been treated by frightfully unprepared doctors upon returning home. In both cases his adherence to societal expectations expose him to physical and emotional damage which ultimately results in his suicide.

Woolf further enforces this reading through her use of tonal cues when discussing Dr.Bradshaw and his sense of proportion. In the article “Tonal Cues and Uncertain Values: Affect and Ethics is Mrs. Dalloway,” Molly Hite argues that for much of Mrs. DallowayWoolf avoids or complicates the use of words or phrases that would traditionally provide readers with “what they perceive to be authorially sanctioned feelings” about the main characters and events (250). However, Hite notes that this absence of tonal cues does not hold for the doctors. Hite argues that,

No reader can have any question about how to take the general practitioner Holmes or the psychiatrist Sir William Bradshaw. Both try to treat Septimus Smith, and both thereby provoke his suicide. The narrative voice speaks directly about these two medical men, providing clear, thoroughly negative tonal cues (255).

I believe that the uncharacteristic use of easily perceptible tonal cues further presses the reader to examine the doctors and their role in Septimus’s death. By examining the doctors and their wholly negative effects on Septimus’s mental state, coupled with an authorial attack on their sense of “divine proportion” and their notion that “health is largely a matter in our own control,” the reader is lead to question and imagine another path for Septimus that spared his life (89, 97). Though Woolf highlights all of these ways that Septimus was pushed to his suicide by a confluence of societally sanctioned institutions, namely the military and medical experts, the medium of the novel does not allow the reader to explore this alternate path in any way, save analysis and imagination. Thus, the clear alternate paths that Septimus’s story could have taken draw the reader’s critical eye in a way that allowing control cannot. Woolf even presents a moment of clarity for Septimus immediately preceding his death which shows him speaking and acting normally. This short and fleeting moment of sanity provides the reader with a glimpse of what man Septimus could have been had his story merely changed in a few key ways.

The medium of the novel allows for Woolf to construct and present a character whose life hinged on a few key decisions and moments that, if done differently, could have resulted in entirely different outcomes. Or perhaps Septimus was always doomed to break down; the reader can never know for certain as novels do not allow for the reader to probe alternate storylines, at least not fruitfully. What we are left with is a character who Woolf constructs as intellectual, if a bit ordinary, who could have been an ordinary person had his society not failed him. Thus, the structural limitations of a novel allow for the reader to fill in the narrative gaps of Septimus’s alternate realities and see what could have been. However, The Walking Dead provides the player avenues to explore and make story critical decisions based on their own thoughts and desires. In providing the illusion of choice and control the game limits the player’s own ability to imagine alternate paths for Lee. The framework of the game removes the ambiguity of Lee’s death and makes it an unavoidable fact. Therefore, although a medium is interactive it does not necessarily lead to greater imaginative possibilities.

Works Cited

Portnow, James. “Extra Credits, Season 2, Episode 21- The Role of the Player.” Online Video clip. Extra Credits. Penny Arcade, 16 June 2011. Web. 15 Apr. 2013.

Portnow, James. “Extra Credits, Season 6, Episode 5- "For Whom The Bell Tolls."” Online Video clip. Extra Credits. Penny Arcade, 9 Apr. 2013. Web. 15 Apr. 2013.

“The Walking Dead’s Faces of Death, Part 3.” Interview by Patrick Klepek. Giantbomb. N.p., 4 October 2012. Web. 24 Apr. 2013. <Giantbomb.com>

"Faces of Death, Part 4: Around Every Corner." Interview by Patrick Klepek. Giantbomb. N.p., 13 November 2012. Web. 24 Apr. 2013. <Giantbomb.com>.

"Faces of Death, Part 5: No Time Left." Interview by Patrick Klepek. Giantbomb. N.p., 9 Jan. 2013. Web. 15 Apr. 2013. <Giantbomb.com>.

genericHenle. “The Walking Dead Game- Lee Gets Bitten.” Online video clip. YouTube. YouTube, 12 October 2012. Web. 16 April 2013.

genericHenle. “The Walking Dead Game- Lee’s Death (Unturned).” Online video clip. YouTube. YouTube, 21 November 2012. Web. 16 April 2013.

Hite, Molly. Introduction. The Waves. By Virginia Woolf. 1931. 1st ed. Orlando: Harcourt Books, 2006. lxi-lxv. Print.

Hite, Molly. "Tonal Cues and Uncertain Values: Affect and Ethics in Mrs. Dalloway." Narrative 18.3 (2010): 249-75. Print.

Iceman26031. “The Walking Dead: Ep 5- Lee Cuts His Arm Off [HD].” Online Video clip. YouTube.YouTube, 21 November 2012. Web. 16 April 2013.

Iceman 26031. “The Walking Dead: Episode 3- Duck’s Death Scene.” Online Video clip. YouTube. YouTube, 3 September 2012. Web. 24 April 2013.

Hocking, Clint. "Ludonarrative Dissonance in Bioshock." Web log post. Click Nothing. N.p., 7 Oct. 2007. Web. 15 Apr. 2013.

Karen DeMeester. "Trauma and Recovery in Virginia Woolf's Mrs. Dalloway." MFS Modern Fiction Studies44.3 (1998): 649-673.Project MUSE. Web. 26 Apr. 2013. <http://muse.jhu.edu/>.

Kathryn Van Wert. "The Early Life of Septimus Smith." Journal of Modern Literature 36.1 (2012): 71-89.Project MUSE. Web. 26 Apr. 2013. <http://muse.jhu.edu/>.

Kealey, E. Women of Britain say – “Go!” . 1915. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington D.C. Library of Congress. Web. 15 April 2013.

Telltale Games. The Walking Dead. Telltale Games, 2012. Playstation 3.

TheAwesomeIncarnate. “The Walking Dead Episode 5 Walkthrough No Commentary Part 5- Hotel Stranger Revealed.” Online Video clip. YouTube. YouTube, 22 November 2013. Web. 24 April 2013.

Woolf, Virginia. Mrs. Dalloway. New York: Harcourt, Brace and, 2005. Print.

Log in to comment