All Heart and All Craft

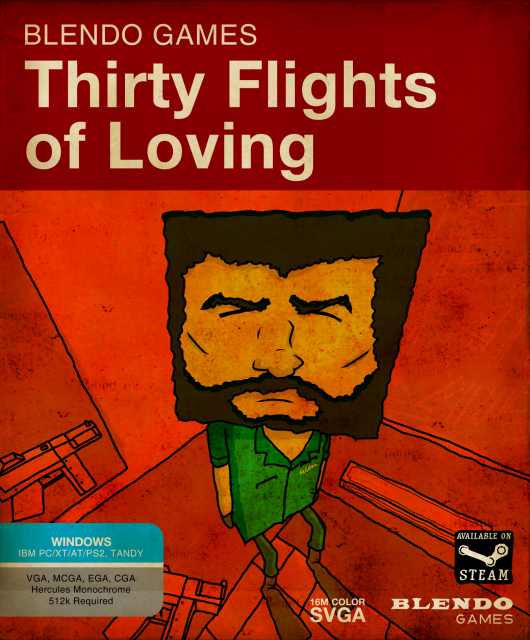

Let’s start at the end. The credits don’t roll in Thirty Flights of Loving, instead we get to stroll through an art gallery wing containing exhibits adorned with the creator’s names. Others remind us of particular set pieces of the game, there’s a bit of the level design prototypes, but it just keeps going.

We walk from one wing to another and are greeted by a plaque dedicated to Daniel Bernoulli. Then there is another one pointing us towards a physical representation of the principle that’s named after him. The principle is critical in understanding flight, and the difference in pressure between the air that flows beneath a wing compared to above it. Next to it is another plaque:

‘All birds need to fly are the right shaped wings, the right pressure and the right angle’

- Daniel Bernoulli

There is another display around the corner of an airplane wing, complete with coloured air to properly highlight the working of the principle. Here is where the game truly ends, and the retrospective analysis begins.

Why is this here? Why didn’t the game just end? What the hell did I just play, anyway?

The Right Shaped Wings

You’re at a bar. The controls are on a handy poster above our heads and there are framed newspapers on the wall beside you. You go down the stairs, underneath a radio playing us a dainty little song, and step up to the bar. The barman and the only patron in the room are staring at you. There’s a gun behind the bar and non-alcoholic drinks next to the prohibition license.

The opening of the game’s aim is to instil you with a feeling of anticipation and uneasiness. Your subconscious should have already made the link between the prohibition laws and the bar to conjure up an image of a 20s speakeasy, and possibly the type of organised crime run from its seedy, dark rooms.

Are they staring at you because you don’t belong in this kind of place? Should you be here?

You click around the room until you find a secret passage and you step through it. You walk down more stairs and are greeted with the box-shaped figures of Borges and Anita. The room is full of weapons, duplicate passports, maps of an airfield’s vault and illegal beer. They’re bad guys. You might be a bad guy too. There’s been no dialogue so far and you’ve only been playing for about a minute.

Thirty Flights of Loving uses this minimalism to great effect throughout the entire game. You are never told where to go or what to do, but due to the smart and salient design of the game, this is never a problem. There is never a wrong way to go and you will never realise it.

Whilst we do not need to know the specifics of where we are, and what the time period is, it needs to be functional and give us a sense that this is a living, breathing and well-realised world. If you were paying attention, you would know that it’s set in a country called Neuvos Aires and its set around the 1960s. We don’t need to know this, though.

You’re a bad guy and you’re part of a heist. Then something goes wrong.

The Right Pressure

The first time you’ll play this game, it’ll take around 10 minutes to play through. It’ll be a blur. The pace of the game will arrest you and you’ll just roll with whatever comes you’re way, regardless of your awareness. You won’t understand it, and in true postmodern style, you’ll either hate it or be interested enough to play it again.

I think that this game is perfectly paced. It has a slow start, gets quicker, slows down again and picks up again for the finale. It’s a typical three-act structure, albeit in a shortened format.

Cut the fat and show don’t tell. Only give us the information we desperately need.

With the minimalist approach to the game, the pace is dictated by the lack of reasons to stick around any of the scenes or locations that you are put into it. If you don’t have any good reason to stick around, then it’s time to move to the next scene. And the next one. And the next one until there are no more.

It’s not a question of a lack of content. They could have added a 2 min tutorial for the controls, a gravelly voice-over of the character’s backstory, pages and pages of internal dialogue complete with snappy one-liners and the repetition of the action scenes. But they didn’t. Because they are not needed to tell the story.

Cut the fat and only show, not tell, the information we need.

This is storytelling at its leanest. Distilled. Purified. One mouse, one button, one plot. The pace of the story is so quick because there is nothing else in the game. There are items in the world only to remind you you’re a real person. Your actions tell the story. The gameplay is the story.

With the frantic pace, however, comes the desperate need for downtime. Peaks and troughs. Build up and climaxes. But when there is only one action scene in the game, the aforementioned heist, you’ve got to get creative. And innovative. They used jump-cuts.

Using jump cuts is something new for games. For all of the craft stolen from film, the jump cut has never been one of them. Understandably, with writers probably never having an in-game reason for them, artists not wanting to have to create another location to jump to, the vast memory it would take to have two locations and models loaded at the same time and the pre-conceived notion of ‘why jump cut when we could have a fancy pre-rendered cut-scene?’

Cut the fat and show don’t tell the information.

Jump cuts add nothing to the gameplay too, and are purely a conceit towards the narrative. Which is why Thirty Flights of Loving utilises them so well. The cuts allow the benefit of flitting between locations and time to particular moments, which simultaneously eliminates the need for expository dialogue and keeps the pace at a constant speed. We don’t need to sit around and mope and talk whistfully about a character’s backstory. Bam. We’re right there. Bam. Now we’re back.

Cut the fat and show don’t tell.

Time lapses are also used in this game. They keep the pace frantic and also to reinforce the theme of that particular moment.

You get back to your teammates. Anita is trying to fire an already empty gun at you and Borges has bullet holes in him. You grab Borges and run through the door and enter a busy airport corridor. You’re running with a wounded man alongside hundreds of people are rushing past you in jerky, time-lapse fashion. The clock’s spinning wildly and Borges is bleeding out. It’s you against them. You keep running and running. It’s tense and everything is going badly.

Cut the fat.

The Right Angle

We don’t get too many games in which you’re the bad guy. Especially one in which you aren’t redeemed in some way. Being a bad is guy is cool. Heists are cool. Getting betrayed and having your team getting picked off isn’t cool, but it is exciting.

Blendo Games knows this. Everything about this game puts in the mindset of a breezy, twist-ladened caper film. The title screen has an eclectic font, a staccato and upbeat song and a couple of lines of burnt-in credits along the bottom of the screen that remains for some of the action scenes. Anita and Borges are a combination of impossibly convenient skills for a heist, which is a fact that is never questioned. There’s two women you are involved romantically with, one good and one bad. There’s a secret party on a roof you shouldn’t be on. Team members turn on each other. An injured man shoots a number of security cameras with spectacular accuracy, before making around an impossible barrier of police. There’s a chase. A car crash. Everyone dies. Maybe.

Games can be about anything they want to be, but are the best they can possibly be when they full embrace the location, the time period and a specific theme and tone. Spec Ops: The Line did this with its wall of sandstorms creating a purgatory-esque location and tone, it’s lose/lose choices enforcing the desperate and uncaring tone of the game . It’s impossibly convenient moments of the game reflecti a generic action-thriller film, which is something that is juxtaposed to great effect with the gradual descent into madness of the once messianic protagonist.

Red Dead Redemption encapsulates the spirit of the great western’s with its embracing of old technology despite the sandbox ethics and it’s epic storyline of the rogue with a heart of gold being dragged back into his sordid past through the wide open and iconic vistas. The small snippets of gameplay like the duels, horseshoes and the horse-breaking mechanics. The embracing of the timeless character tropes. Carriage heists. Town drunks. Black hats and white hats. Sunsets.

Each of these games worlds are incredibly well realised, making it one step easier for the player to get fully immersed in the game. Thirty Flights of Loving gives us scant, but purposeful, details of its unseen outside world. It’s collection of city names seen on the airport departure board. The world’s level of technology in the form of its weapons, vehicles and airplanes. Its eccentric architecture. It’s ‘Big Brother’ style ethics towards privacy in the form of the floating cameras and the use of wanted posters in major airports.

Being the bad guy will always be cool, and Blendo Games have figured out a whole bunch of ways it can show us why.

The Bird Who Needs To Fly

Thirty Flights of Loving arrests you like no other game, and demands that you play it. It’s breakneck pace, it’s basic but charming visuals and its crumb trail of a narrative creates a unique gaming experience. How many times do you sit there and think about a video game plot? How many times do you have to in order to discover the full intricacies of the plot?

This game confronts you with the question of: 'Are you actually ready to properly analysis a game?' If you aren't, then maybe this game isn't for you.

Regardless of whether or not 'you get it', this game is made up of all heart and all craft. It's determined to show you something that you've never seen before, and is going to do it uncaring of whether or not you like it. This game incredibly confident in its own abilities and ideas. It’s fuelled by bravado and sheer intuition. This is your Kill.Switch. This is your Dear Esther. This is your Braid.

Is it actually a game? No, not really. It's more of a combination of craft textbooks. Advanced Video Game Narrative. Video Game Minimalism 101. How To Pace Your Game Properly.

Is it one of the 'great' games? No, but it's one that we can, and we should, learn a lot from.

Log in to comment