Silent Hill and Resident Evil may no longer fill our hearts with terror, but the horror genre is alive and well in the hands of smart independent developers who aim to make us cry in the night.

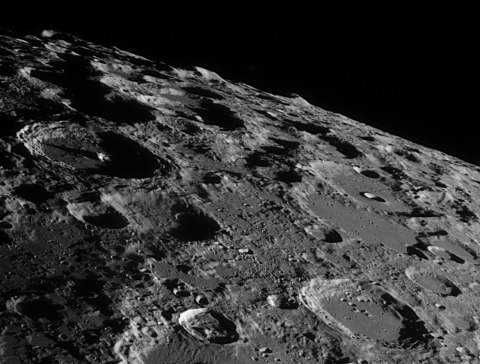

Aaron Foster has spent years creating his own mods for existing games, but nothing really captivated him, and they never quite saw completion. He spent a few years in the traditional games industry, but it didn’t last long. Foster soon saw himself looking towards the moon, an object both familiar and mysterious, and heard the siren song of a horror experience waiting to be crafted.

The result is Routine, a game Foster is currently working on with his partner, designer and artist Jemma Hughes, and Pete Dissler, handling programming duties. It’s a small group of dedicated individuals hoping to bring something new to horror. Routine’s primary distinction is permadeath, as you will no longer be able to spring in the darkness without risking everything you’ve earned. It’s not quite a roguelike or roguelikelike or roguelish or whatever we’re calling them these days, as the world of Routine always stays the same, no matter how many times you play. If you want to find out what happened here, you’ll have to be careful. Death has consequence.

Unlike other horror games as of late, Routine has combat. The robotic nightmares strolling the halls of the game’s moon base have your number, whether it’s in the darkened halls or an underground reservoir of water. While Routine isn't out until next year, Foster hopped on Skype to chat with me, just days after it was revealed the masters of modern indie horror, Frictional Games, would be jumping into similar territory with SOMA.

No pressure.

Giant Bomb: Hopefully Skype doesn't crash...

Aaron Foster: Before we all moved in together as a development team, we actually used Google Hangouts as our virtual, little studio. It was really helpful because you can screenshare all the work you’re doing to the other team members.

GB: Are you guys all together now?

Foster: Well, there’s only four of us. Three of us are--we’ve rented out a flat together and we’re using the front room as our studio. The fourth one is in Australia. [laughs] He’s a freelance audio guy. He works on a lot of other projects, not just us.

GB: The core three of you, then, had you worked together, in the past, before starting Routine?

Foster: Not at all. One of them, Jemma, she’s actually my partner, and I’m teaching her the art side of things for games. Pete, the programmer, he was working on his own thing before I met him. We did a sort of skill trade at the start when I first got to know him. I did art for one of his projects, and he did some programming for one of mine. We just worked really together, so he’s part of the team now.

GB: Do you have an assigned designer, or are you all contributing to the design of the game?

Foster: Well, I founded Lunar Software, and Routine started off as a one-man game just from me. So because of the way it started out, I’m kind of the lead on this project, but we all chip in to design. Whenever I have an idea or a change, I express it to everyone, everyone has their input, their worries--we brainstorm it that way. Whenever they have ideas, we all discuss is and see what we can do with it. It’s a really organic, iterative process on the design. But we have these core values that we don’t want to change that we’ve had from the start.

GB: What would you describe as the core values of Routine?

Foster: One thing that’s never changed is the idea of having this consequence to your actions, which a lot of games try to avoid, actually. A lot of games try very hard to not kill the player, to keep the story quite seamless. Even boss fights in games a lot of the times are quite a lot easier than the level because they don’t want you to die in the epic moment of feeling great, and expressing that story to you. Consequence in our game has been a really big focus. We started off using permadeath as that pivotal thing, making sure the player knows that if you don’t pay attention to what you’re doing, there definitely are consequences. We’re trying to explore that side of things. Also, having it non-linear, so that you don’t have to replay the same thing over and over if you do die...the base is completely open for you to explore and figure out what’s going on. Also, to top it off, there’s multiple endings, depending on what you find out.

Please enter your date of birth to view this video

By clicking 'enter', you agree to Giant Bomb's

Terms of Use and Privacy Policy

GB: I find myself struggling when I play roguelikes or roguelikelikes--however you want to classify it--but essentially the idea of jumping into a game and playing it repeatedly over and over again and trying to learn from that experience. I have trouble with some of the games that don’t have a proper end because I like the finality to it, I like that I can say “okay, I saw this to its conclusion,” and I can move onto the next thing.

Foster: Oh, no. I guess another thing with roguelikes, you have these randomized environments a lot of the time, right? I just stayed away from that for a big reason: we really have this story that we want to tell in the environment. If we randomize it too much, then it’s hard to have this really specific story. Things get too muddled up, things get too vague in areas. So we tried to keep the environment quite static because we have a story we want to tell in it. But everything within the environment can change. There is a story that you find out, but in any one person’s play through, you might only find out one side of it. They will come to a conclusion that they thought was the right thing--the right path to go down. Kind of [a] vague answer…

GB: No, I completely understand. I was talking with Thomas Grip, the designer on Amnesia, and one of the things that he talked about is that whenever they started a new project, they tried to include a little more variability in terms of what the player encounters. But they often found themselves going back to...not necessarily scripted moments, but definitely in horror, you have to control the environment to some degree to make sure you can build that tension.

"One of the most important things for me for tension in most horror games is the unknown, not knowing what’s going to happen."

Foster: Absolutely. One of the most important things for me for tension in most horror games is the unknown, not knowing what’s going to happen. But also the developer needs to somehow have control over the player so he experiences things in a very specific way. When you have an open game like we do, it’s really difficult to get the balance right--keeping it varied but also purposely trying to create tension at a certain point. That’s one thing that we’ve definitely struggled with with Routine. We feel like we’re getting to a point where it’s quite interesting now, and we definitely have one or two sections in the game which...if you want to find out a specific ending, then you’re going to have to go through. In those points, we can definitely control things a little bit more. It’s a strange thing. It’s a really fun design challenge, though, I think, for an open horror game.

GB: It’s not like a film or a book where it keeps going regardless of what you do--the player has agency. That agency means that they can fail. But when they do fail, they may have to go through a specific sequence a second or a third time, and each time that diminishes the tension. For Amnesia, Thomas walked me through the water sequence. I got through that moment in one shot, where you almost get killed but I made it out. He walked me through how on the second and third times, they change up what happens, so you can’t immediately apply what you think screwed up with.

Foster: We have to. If we don’t, there’s no point to it being open. The way that the A.I. is programmed is that we, as developers, almost don’t know where they are most of the time. So you’ll do things in the environment that will attract your attention. We, as developers, don’t control what the player will do or when he does it. There’s lots of things in the environment. Accessing computers, which you saw in the trailer, when you do that, if you stay there for too long, it will set off an alert, which will gain attention to your whereabouts, basically. We tried to control it through that way. The pace of the game is kind of related to the pace of the player and what he’s doing. I feel like we have to tackle things a little bit more in that direction. It’s a strange thing. With Amnesia, it’s probably the scariest modern horror game you could probably find for most people, right?

GB: 100% agree. You should get a t-shirt for finishing that game.

Foster: [laughs] Right. Personally, I really like Amnesia, I think it was scary when I played it, but like you said, when you die, to me it’s a big issue. Dying in games is always a big issue to me, regardless--not just Amnesia. It’s any game. Feeling no consequence to dying, where you can just reload a save two minutes ago, always, to me, removed all of the tension of dying. From that point onwards, I would play around, I would relax a little more. Sure, there’d still be a bit of tension because the audio and what’s going on, but it’s not the same. I don’t feel tension for dying at all because I’ve got no worries about dying if I’m not losing anything. I know permadeath is a love or hate sort of thing, and we’re okay with that. We know that the game is not going to be enjoyed by a lot of people, it’ll hopefully be enjoyed a lot by a few. That’d be okay for us, I think.

GB: When you talk about the consequences of death in game design, it essentially allows you to deconstruct the systems in a way the designers didn’t want you to. If you die, suddenly the tension is lost, and you can start poking and prodding at the systems to figure out how to get your way through in a way that wasn’t intended.

Foster: Absolutely. A lot of people associate permadeath with difficulty. Because it has permadeath, the game’s going to be hard. That’s not the case with us. We didn’t put permadeath in there as a difficulty curve. We actually put it in there purely to make the player understand that there are consequences to his actions. He can just throw away everything if he’s not careful. I didn’t finish Amnesia. I’m not a big fan of puzzles, and the puzzles in Amnesia, to me, were a difficulty curve. If I’m not very interested in them, I’m not going to put a lot of effort into figuring the puzzles out. Therefore, I get a little bit stuck on finding the pieces and putting them in and so on. To me, that was it personally because I’m not as interested in puzzles. It was a bigger difficulty curve than a difficult platformer or something. It’s interesting. Ideally, for me personally, a player may not die at all from start to finish but he knows that if he does die, then he will lose everything. That would be the perfect scenario, just like your situation with the water monster. You got it perfectly your first time, but you had that real close encounter with death, with dying. It was a perfect setup for you. Ideally, that would happen in Routine, too. [laughs] But you’re trying to make sure that if you do die, there’s definitely huge amounts of variation, and the way that you play again is up to you. It’s not just repeating the same thing at all.

GB: When you started imagining Routine and it was going to be a one-person thing, how difficult was it from what we’re seeing now?

Foster: Oh, it was so different because I’m not a programmer at all. I chose Unreal because it has visual programming called kismet. It lets non-programmers really get [into design] on a technical level without knowing exactly how to code. I mean, you still need to understand logic behind coding, you don’t have to understand a language, basically. It was a simplified version of Routine, for sure. It didn’t have any of the computer interaction that you see now. The enemies would have been...maybe even non-existent, honestly. It would have been, I hate to say it, but it would have been much more of an atmospheric, singleplayer almost Dear Ester type thing. That was just because of my own skillset. As soon as Pete got on board, I was able to design it into something more horror oriented, which is where a lot of my passion and inspiration comes from from a lot of creative aspects.

GB: If you released it yourself, it would have been maybe atmospheric but maybe not as scary because it wouldn’t have had any enemies.

Foster: Oh, absolutely. I grew up watching horror and sci-fi since I was a kid at a very young age, age 10 or 11. My mum was good friends with a video rental store that was across the road, so I grew up watching 2011, Alien, The Thing, and it just inspired me so much through my childhood, to this day. It would definitely had a similar vein, a similar atmosphere--just mechanic-wise, it would definitely have been extremely cut down, basically.

GB: Prior to working on Routine, have you had an opportunity to express your interest in horror in game development?

Foster: Well, yeah. I guess it is my first chance properly. I’ve been doing mods and small things for about seven years now. I worked in the industry for a few years as a 3D environment artist. But it just got to a point where I had to settle down and just do something. I did so many little projects in the past that I weren’t fully passionate about, and that’s why it never got finished. Choosing Routine was something I knew that, from the start, I would never get tired of this because it’s been something that’s stayed with me since my childhood. I would just continue going at it until it’s done. And it is. We’re quite far ahead now. It’s the furthest I’ve gotten with any personal project.

GB: Well, now you’ve got a bunch of other people excited for it. You’ve gotta finish it!

Foster: We’re very surprised with the reception. We had bets, actually, when we first showed our trailer. We all had bets about how many views we might get. I think I was on about 6,000, and I would be very happy about that! 6,000 views for a trailer! I knew the trailer got over 400,000, and I’m genuinely completely surprised. 6,000 would be...I would be happy about. It would be great. I thought this was quite a niche game, but probably because of the recent trend of horror, it’s really helped with our game for sure, especially with popularity.

GB: It’s been really interesting to watch that. I’ve been a horror guy for a long time, and horror essentially died out in terms of the AAA games. You’ve got a couple of things: The Evil Within is coming out, there’s a bad Silent Hill game every couple of years, and Resident Evil has gone so far off the track if you’re talking about a pure horror game. But AAA has gotten away from it in pursuit of being more action-oriented, which for all sorts of reasons makes sense. But it’s been super fascinating, especially in the post-Amnesia world, where Amnesia proved out that “hey, you don’t need to have guns.” As soon as you start putting some of those mechanics into your game, the expectations for how guns should handle and how combat should handle is pretty high. Games a pretty good at doing combat!

Foster: I completely agree. Doing a sci-fi fhorror game, that there’s even less of those. In fact, Dead Space 1 was pretty good. It had a lot of action but it still had a lot of tension for me, personally. System Shock 2 was the last one that I can remember when I played that. Tackling a sci-fi horror game would be, in my opinion--the Frictional guys are doing it, as well.

GB: I was going to say: you guys have to be at least a little bit nervous.

Foster: I guess so, but if you look back at our expectations of only having 6,000 views and that would be enough…[laughs] We’re okay with that. We’re okay. It’s hard to compete with Frictional. This is their sixth game, is it? Their sixth horror game?

GB: They’re pretty deep on iterative process on that genre, for sure.

Foster: Yeah. I don’t see it as a competitive thing, more...it inspires it. It’s really exciting to see a new sci-fi horror game. There aren’t many of them out there, and I would love to play another one. Sure, it’s going to compete, and destroy us in some way, but I’ll really enjoy playing it. [laughs] What did you think of Outlast and Amnesia? Did you play ‘em both at a similar time?

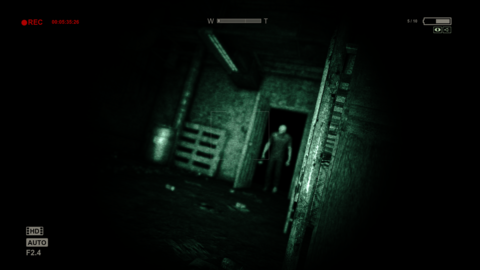

GB: Yeah. I tried out both games for Quick Looks on the site. I like to play ‘em one at a time. Going back and forth would have weirded me out. I played Outlast first. It relies too heavily on jump scares in a way that was effective but got tiresome once you realized that was, essentially, most of what it was relying on. The handheld camera also worked really well, but I don’t think they exploited that part enough, and often relied on the darkness to conceal something that popped up out with some violin noises.

Foster: I’ve played both. I completed both Outlast and A Machine for Pigs. It was a really interesting thing. I played Outlast first, as well, and I think a few days later I played A Machine for Pigs. As a game, on any core gameplay point-of-view, obviously I enjoyed Outlast more. I wasn’t scared in either of the games, but I really loved A Machine for Pigs’ setting. The story and that sort of setting, the whole idea of the machine is so abstract. It had a touch of City of Lost Children vibe, if you remember that movie. I was really interested in the setting, for sure. And the soundtrack was absolutely stunning in A Machine for Pigs.

GB: That introductory track that plays just on the menu is so, so creepy. A Machine for Pigs has gotten a bad rap from people. It should less be looked as a sequel to Amnesia and more a sequel to Dear Esther that happens to be set in the Amnesia universe, as much as you want to consider that a universe. In Kotaku’s review, the writer proposed that “wouldn’t it be cool if Amnesia just became an anthology series?” Taken on its own terms, I think it’s super effective.

Foster: I think so, too. Setting wise, it was much more interesting than The Dark Descent, but it just didn’t have that fear, that scare, that tension.

[SPOILERS FOLLOW FOR AMNESIA: A MACHINE FOR PIGS]

GB: It’s best recurring sense of tension, and the one that worked best for me, was when they reintroduce the water creature as a nod to the original game. I think you go a solid 30, 40 minutes where you become convinced that water creature is chained off from you, and you’re never going to encounter it. Then, there’s the moment where they pull the rug out from under you, and you have to run from it. That was probably the most effective scare in the game.

Foster: For me, personally, it was the first time you saw the pig. I think it was with all the cages? I don’t think I expected it to be there because the buildup to that point was quite a long time. I got it in my head that maybe you don’t see it until a good while. I don’t know why. It just felt like the buildup may even go longer because it went long enough. When I saw it, it was a nice little bit. It was a surprise. I think after that...the water creature didn’t do much for me. The bridge collapsing was definitely a nice surprise, and definitely sprinted from that and it was great. But I think that first bit with the pig, to me, was a little bit more, tension-wise. But it’s interesting to see what the Let’s Players experience in the game because that’s one amazing trend. Just getting to see people’s experience with horror, and how they handle certain scenario, for sure.

[SPOILERS END FOR AMNESIA: A MACHINE FOR PIGS]

GB: I streamed maybe half of Outlast in total, alongside our audience. I had people reaching out saying they’d gone and purchased the game on Steam, not because they had any interest in actually playing it themselves, but because they were interested in watching me play it because they didn’t have the balls to get through the game themselves. They felt like they owed something to the developers. That’s maybe 1% of the audience, if even that?

Foster: But it’s lovely that some people think that.

GB: Right! But I think it’s really interesting--games are so much different from movies or books. You can just close your eyes and the movie keeps going, but the game, you have obstacles, you have to be the one that goes around the corner. I think that’s too much for some people. Some people want the rollercoaster ride, but they don’t want to pilot the rollercoaster. They’re happy to leave that to someone else. In some ways, you have the architect of the horror, which is the designer, but then you need a pilot. The pilot are these Let’s Players.

"The moon in particular is something I’ve been interested in for quite a long time. It’s so close, we see it all the time, but we know so little about it, really."

Foster: That’s a weird thing to think about the Oculus, how the Oculus can be used in horror--it just enhances the experience so immensely. Other genres, for sure, will take advantage of the Oculus, as well. But I was just looking at a point-of-view that a lot of people are afraid to experience and play these games without the Oculus, with the Oculus, to me, I found that because you have such a sense of being in the environment with depth and such--I usually squint my eyes if I get quite scared. I wanna see what’s going on but I wanna blur the details. And because you’re wearing the Oculus itself, even if you close your eyes, it still really feels like you’re there. Just looking at how horror games will benefit from that is really interesting. But it worries me from a mass market point-of-view [laughs] that not many people will go ahead and get it, which is a shame. I think Oculus is such an amazing thing--potentially, at least.

GB: Yeah. Every October is a chance for me to try and find something else to scare me because I’ve seen so much at this point that it does take quite a bit. I can be scared, but the truly memorable moments are very few and far between because I’ve seen it all. But the Oculus is something else. What it does it breaks down a lot of the coping mechanisms that you use when you experience horror or choose to scare yourself. For example, one of the things that I find myself doing is that I put additional distance between me and the monitor. I will actually edge away. In the Oculus, you can’t do that. The display is right in front of you. The scares didn’t even have to be very good. We’re talking really shitty character models. It’s gonna be too much for a lot of people.

Foster: Yeah, absolutely.

GB: If it was making me uncomfortable, I cannot fathom what it would do to the average person. I legitimately think an Oculus could give someone a heart attack, and I mean that with some sort of seriousness!

Foster: I completely agree, though. I’m someone that’s been exposed to horror, I actively do it on a constant basis. I love to get scared. And it’s been a long time since I was genuinely, genuinely scared of something. The last I can remember is maybe Blair Witch when I first watched that and the end scene in [rec], the Spanish version.

GB: That last ten-minute sequence is just unbelievable…

Foster: Things like that are very rare occasions. But the Oculus, like you said, even very quickly executed, developed products that, obviously, haven’t been developed for a long time, definitely still had a big impact. Have you tried something called Kraken?

GB: Hmm, no. Can you describe Kraken at all?

Foster: It starts off with this pretty bad...you’re in this rock cave scenario. There’s basically a light house in the distance that you have to walk towards, swim towards. I won’t spoil it, but I’d recommend giving that a go and see what you think.

GB: Yeah, I just loaded it up. Kraken “Sea Horror Demo.”

Foster: Yeah, it was an interesting one. I’m terrified of the water, so, to me, that’s a perfect situation to scare me. They did a good job, I thought. Pretty good job.

GB: So where are you guys at in terms of development? Are you heads down, just refining everything?

Foster: We’ve kind of got a little bit of savings that we’re using to fund our project. We haven’t got any backers or any publisher or anything. So, ideally, we’d like to go as far as we can with these savings, and making the game as good as possible. We did a crappy mistake early on giving people an estimated release date. Definitely learning from that on our next project. [laughs] At the moment, it’s ASAP, but we will not release the game until it feels right, until it’s good and ready. We’re aiming to get it done earlier next year, but it’s hard to say that at this point. I think at Christmas time we’ll know a lot more. At that point, we should be at a stage where we’ve pretty much finished everything, and it’s just polish and tweaking things and getting things right.

Again, at the start of the project, the base was actually quite large, quite extensive. We realized that there’s almost no point to having it that big if there’s nothing interesting and unique going on in all these environments. So we cut it down to make it sure that all the places you go to has something at least unique to it in gameplay and feel and atmosphere. That really helped cut down development time quite a lot. It actually makes the game a lot nicer, more concise, gets the point across much better.

Probably one of the slowest things with game development has gotta be the environment, level design, and environment art, as well. It takes such a long time getting all that done, and usually at a company, that’s probably the biggest amount of stuff you’ll get is the environment art and level design team. That part is just taking the longest time. I may get help from one or two people, getting some environment props done, just to alleviate some of the time on that, I think, but the game, as a core, is definitely there. But there’s still lots of things that we want to try out and test to get a feeling just right. A game, especially with permadeath, you’ve got a lot of things to work out, to make sure it doesn't feel too annoying, and trying to make the process of trying to get [to the end] oo painful, basically. We’ve got some good iteration, a solid bit of iteration to do, over these months.

GB: When we spoke over email, one of the things you expressed was a real anxiety over how much to show about the game. In the ideal world, you’d show nothing and just release it.

Foster: Oh, absolutely. You ever watched the making of Alien, the first Alien movie? Ridley Scott, pretty much throughout the whole production of the movie, he never showed the actors the alien character. They asked to see it quite a lot of times but they never showed it before the time when it comes to shooting, right? It’s just the idea of even making the actors feel uncomfortable. I kind of embraced that and I love that so much. Like you say, if I had my perfect scenario, I would love to just put out an idea to everyone that there’s this atmospheric, horror exploration game set on our moon, and give people a few ideas of mechanics, but not express too much of what the game is about. If that interests people enough to buy it, then hopefully they will probably enjoy the game the most.

There’s people that ask for more information. I try not to convince those people to buy Routine, I try to convince them that if the stuff they have seen already doesn’t interest them that much, then the game might not be for them. I know it’s a hard sell when you say “here’s this tiny scrap of information, you might not enjoy it at all or you might love it, I’m not sure. I’m only going to tell you this much.” It’s hard to ask for people’s money when you’re doing that, obviously. But I guess I’m baffling on a bit about it. [laughs] To me, the fear of the unknown is just such a powerful tool. I think more developers should do that through marketing, for sure. I think people show far too much a lot of times, especially on horror games.

GB: The last question I’ll ask you: why are people so afraid of space?

Foster: The moon in particular is something I’ve been interested in for quite a long time. It’s so close, we see it all the time, but we know so little about it, really. We’ve been once or twice, a few times, with very primitive tech, and I think it’s one of those places that, honestly, feels to me extremely lonely. If you’re standing on the moon, you can see all of Earth, but you couldn’t really contact everyone. It feels so desolate and lonely to me that I just felt like it had to be explored in a sci-fi horror setting, for sure. With space at all, you have the idea that it’s pretty much this form of isolation, in a sense. You don’t have contact with almost anyone. To me, that’s what’s really interesting about sci-fi, the sense that you can’t really connect with many people. Our moon is just an interesting setting, I think, just because of how close and apparently relatable it is because it’s our only natural satellite.