(There aren’t major spoilers for the Zero Escape series here. Think of this as a companion piece to my spoilercast for Virtue’s Last Reward. This is really meant for people who don’t know what Zero Escape is.)

It’s not easy to play new games. By that, I mean genuinely new games. We’re not talking sequels or spin-offs and iterations on what you’re deeply familiar with, the painfully similar experiences you’ve had a thousand times over. I’m going through that with Fire Emblem: Awakening right now. Several times, I’ve wanted to put it down, and turn on...well, anything else. Devil May Cry. The Cave. Whatever, it doesn’t really matter. Stuff I know I’ll like. It’s raised the same question I asked myself during late nights terrified with Amnesia: The Dark Descent: why am I doing this?

You do it because it expands your palette. You do it because change, even when bad, is good. You do it because sometimes other people are right. In the case of the Zero Escape series--999: Nine Hours, Nine Persons, Nine Doors and Virtue’s Last Reward--it turned out these people were very, very right.

I don’t even feel that bad for having put off the journey for so long, either. There were good reasons, which I’ll get to, but I’m getting ahead of myself.

At the bare minimum, if you can appreciate a good story, you’ll enjoy the Zero Escape games. If you can exercise a serious amount of patience, you’ll be rewarded with a game that respects the player’s ability to connect the dots. At their core, both 999 and VLR are smart, fun, sprawling stories that begin by telling the player nothing, and end by telling the player everything. (Of course, in reality, it’s just enough to feel satisfied, while teasing the bigger picture.) More importantly, there’s a surprising amount of logical consistency. Unlike so many other stories rooted in mystery, Zero Escape begins with the implicit promise that, yes, it will pay off eventually. That’s less so in VLR than 999, as 999 was conceived without a sequel in mind, but in many ways it’s true for both.

What’s the Zero Escape series, anyway? A good question for the many people who weren’t the group of vocal fans who were constantly asking one of us to just play the damn games.

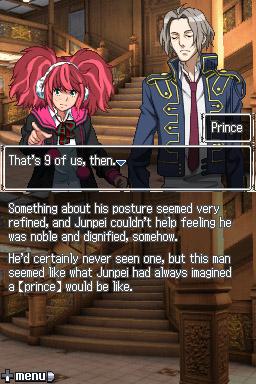

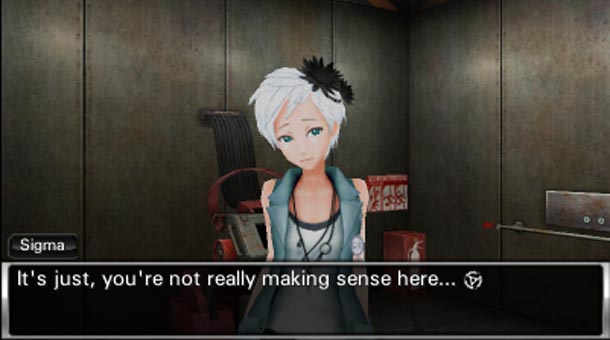

Both are visual novels. Visuals novels are an evolutionary split from the adventure game, an interesting hybridization of the player choice offered in text adventures like Zork and the heavily authored stories present in the “classic” adventure games from LucasArts' heyday. What this practically means is visual novels are largely about reading, making decisions, unlocking cutscenes, and watching those cutscenes play out in different ways when you load it up again. Often, this is required to understand what's really happening in the story. Some visual novels have puzzle elements, some do not. 999 and VLR have their puzzle elements baked into the fiction.

999 was released on the DS, and is easily obtained from Amazon. It's only $20, and the only way to the play the game. There is a very specific reason why it couldn't be ported to another platform, at least one that didn't have two screens. The sequel, Virtue's Last Reward, was released on both 3DS and Vita last year. The 3DS version has the advantage of a second screen for taking notes, which I found infinitely useful. Unfortunately, it's also hobbled by a crippling progress-erasing bug that occasionally crops up when saving during puzzle sections. I never ran into it, but it's worth keeping in mind. The Vita version does look better, and has trophies, if you're into that.

By the way, don’t search for the term visual novel on Google image search, or you run the risk of turning yourself off from what I’m about to advocate for in this piece. Then again, supposing you’re not at work, click here. A gallery of innocent and often sexualized depictions of women is what you'll find, and it’s what I’d surmised about the genre during my brief investigation into it. I wrote it off, truth be told, and didn’t feel bad. Who would want to play that?

(For what it’s worth, I do take issue with some of the sexualization in these games, which I’ll get to later.)

In 999, there are nine people who have been kidnapped by a man/woman/it named Zero, who has locked them on a quickly flooding boat. And it might be the...Titanic? Each person has various levels of short term amnesia, thanks to the gas used to knock them out, and very few know one another. Everyone has a device attached to their arm that’s accompanied by a number, and the devices are used to enter the nine doors around the ship. If you find the door marked “9,” you can leave--everyone can leave. Players must follow specific rules, though. Breaking the rules means a bomb in your stomach explodes. Zero, through a loudspeaker, explains this is all part of the Nonary Game.

It’s impossible to explain the setup for Virtue’s Last Reward without getting into spoiler territory for 999, but you won’t be surprised to learn it also involves a bunch of people being kidnapped by a figure named Zero. Anything more would start giving away part of the fun.

That fun involves a whole helluva lot of reading, and it’s not handled well in 999. The budget for 999 wasn’t very high, so there’s no voice acting, and everything’s text. That’s good and fine, except the text moves extraordinarily slow, and it’s not until you encounter an ending for the first time that you’re given the option to make that text move any faster. The second time around, holding down on the d-pad automatically skips any text you’ve already encountered. It still means you’re sitting through a fast-forwarded version of old sequences, but it’s nonetheless an improvement.

Justifying why one would want to play 999 a second time without getting into the nature of what’s really happening is tough. Here’s how I’d explain it, and how I’d warn anyone about to embark on 999 for the first time. You’re going to spend a bunch of hours playing this game, and encounter what’s called a “Bad End.” It’s not an ending that will provide any closure--in fact, it will only confuse you more. Upon unlocking this ending, it will become clear there are multiple ways to finish 999. It’s pretty obvious how to experience the various divergences, as the game often asks the player what group he would like to be a part of. Many people warned me about this going into 999, and I can’t imagine what it would be like to play 999, run into a “Bad End,” and assume that’s how it's supposed to play out.

There are six “real” endings in 999, and nine in VLR. In total, however, VLR has 35 endings. That’s a somewhat disingenuous representation of VLR, since a “Bad End” in VLR is not one of the “real” endings. I know, we’re getting into some seriously bizarre semantics, but stay with me.

You need to see most of the endings in both games for a few reasons.

One, it all does mean something. Truly! That sounds really vague, but it’s also really true. There is a reason for playing through 999 and VLR multiple times, and it goes much further than just seeing how a story can play out in different ways, ala your traditional choose your own adventure story. To say anything more would be skirting around what’s happening in the Zero Escape series, and the discovery of these revelations is much of the appeal. But trust me when I tell you there’s a real payoff for the investment, even if that investment means playing through some of the same sections over and over again. Just hold down on the d-pad, and you’ll make it through okay. I did!

(Thankfully, VLR meaningfully addresses and largely solves these issues by visualizing the game’s timeline and allowing the player to, at any time, jump around the multiple decision points.)

Two, it’s necessary for the payoff. Part of the hook in both 999 and VLR is encountering dead end after dead end, beginning to put the pieces together (wrongly, in almost every case), and marching towards what is called the “True Ending.” This is where all the cards are put on the table, and the story presents its true self.

Nothing about 999 makes any lick of sense for the longest time, but the oddities about your situation, and the continued acknowledgement by your character about the increasing stack of oddities, pushes you to keep going. The main character is aware things are weird, and logic has been lost. When characters don’t do that, the audiences agonizes. Sometimes, this split between what the audience wants and what the characters actually do is played up to dramatic effect, such as the lonely babysitter walking around the house alone to track down a noise in a horror film. Other times, it’s an overused narrative device mean to to kick the can down the road, like in LOST.

Yes, I just took a pot shot at LOST.

So long as there’s a legitimate payoff, that’s all fine, and 999 pays off like a son of a bitch. Over here is the picture I took of myself after unlocking the “True Ending” in 999.

The games are hardly perfect--don’t get me started on the puzzles--and their issues go beyond repetitive text. Both games are guilty of sexualizing characters for no good reason, undermining the huge amount of time it spends fleshing each of them out. In 999, it’s Lotus. In VLR, it’s Clover and a character whose name I can’t say, since it would be a spoiler for VLR. In any case, keep in mind how these characters are dressed. You might think each of them are depicted as floosies, but that’s not the case. Each are smart, independent, and bold women with interesting back stories, characters who are cut off at the knees by what one would hardly call clothing. It plays into the worst stereotypes of Japan’s depiction of women, and an early reason why I’d dismissed both games. Maybe these characters just like to dress this way? Let's assume that's true. It hardly forgives the game's repeated indulgence of the player's character cracking cheap, juvenile sex jokes at the expense of every single one of these characters. It comfortably discredits the argument the characters were designed this way other than to be provocative. The next Zero Escape game would do well to dispense with this.

Try to put that out of your mind, and you’re left with some awfully special games. They’re not for everyone. I wouldn’t blame anyone who rolled their eyes at spending 50 hours with games that spent most of their time talking to you.

If you take the same leap of faith I did, though, you’ll be happy you did.

Also, your brain will explode. Promise.