When we discuss games, we almost always talk about them as assemblages of experiences that anyone who plays them will undergo. And why not? We're used to media that consists of set series of events; it's what we see in books, films, and television programmes. Like with movies or TV shows, we boot games by placing a disc into an electro-box or by clicking a tile in a media library. Multiple people can play the same game and come away with experiences of the same mechanics, and sometimes the same challenges, set pieces, and story beats. Just as everyone who watched Casablanca saw Rick kiss Ilsa, everyone who played Bionic Commando fought the helicopter. Anyone who read Moby Dick to completion will remember Ahab going down with his ship, and anyone who played Worms for long enough will be able to reference blowing their opponent to kingdom come with the Holy Hand Grenade.

Our discussions about games are reliant on us having these mutual reference points which we can always indicate to each other. Yet, almost no two run-throughs of a game are identical, and most games use inconsistency between play sessions to entertain. If you and I both play a round of Seven Wonders, our degrees of success and the paths we carve through its challenges are likely to be poles apart. We could both beat Bloodstained: Ritual of the Night, but if I start ranting on about how cool the Revenant boss was, you might have no idea what I'm talking about. That undead warrior is a deviously hidden Easter Egg.

Some games or some techniques for playing games aim to control their variance more than others. There'll be more surprises in an evening of Uno than there will be on an amusement ride like Hot Dogs, Horseshoes & Hand Grenades. Fewer specific events are guaranteed to happen to you in a round of Fall Guys than in an expert speedrun of Vectorman because speedruns use painstakingly optimised routes. However, any semblance of randomisation or audience agency means that runs of a game can be asymmetrical. Even in our "controlled" examples of Hot Dogs, Horseshoes & Hand Grenades and Vectorman, no two plays are likely to be indistinguishable. Whereas, a book, film, or TV show plays out the same every time.

So, we seem to have a paradox where the contents of games are simultaneously fixed and varied. One where our experiences of games are shared and yet unique. How do we resolve that? We can say that some parts of games change and some don't, but that's a wishy-washy answer. It doesn't tell you what changes or why. I think an elegant resolution starts by looking at a particular ambiguity in our use of the word "game". We can use "game" both to mean a set of rules for play and a single instance of play within a ruleset. E.g. There's a difference between the game of snooker and a game of snooker.

The game of snooker is a type of activity defined by certain limitations and goals like "You play on a table with six pockets", "The winner of a frame is whoever scores the most points", and "Players must pot the coloured balls using the cue ball". A game of snooker is an event or series of events in which people act according to those rules. A game of snooker has specific players, a location, and a time period it takes place in. There are certain conflicts and outcomes inherent to that one game. Players act within the game's rules to cause these events, and the game's ruleset contextualises the events. Maybe Player A came out victorious by scoring higher than Player B. Maybe Player B pocketed a cue ball at one point and fouled out.

The snooker example uses a highly traditional concept of games, and we'll build on it to talk about more modern game formats in a minute. What's relevant for right now is that this demonstration resolves our paradox for many older forms of games such as sports and card games played with a standard deck. We share our experiences with games under the definition of "games" as sets of rules. However, our experiences of games differ under the definition of "games" as individual play sessions to which we apply those rules. What we have in common are the guidelines by which we conduct a game and some experience of working within those guidelines. But we can each encounter many different events while applying those rules, even if some events are common to certain games.

If you and a friend have both played Texas Hold 'em, then you can share with them the experience of betting chips, trying to build a strong hand, and watching community cards get revealed because that's what the rules dictate. If you're a regular at Texas Hold 'em tables then winning with an ace-high straight is an experience you'll share with some players of the game but not others. However, never will you and another fan of the game see identical rounds unfold in front of you. The odds are just too astronomical that the betting and the distribution of the cards in each instance would mirror the other. The disparity between experiences in these ace-high and non-identical round examples is due to them arising from more than just players following the rules. They are the result of precise player choices and unique randomisation of the cards which occur while following those rules.

Let's look more closely at how randomisation and player agency allow for a range of experiences across separate plays of one game. Manifestations of randomisation include procedural generation of levels, enemies randomly picking one action over another, and different cards being dealt as the result of a shuffle. Not all games use randomness, but all games accommodate varying player inputs. Changes in player behaviour could be down to how they tackle a problem, how they customise a tool, or where they do and don't explore.

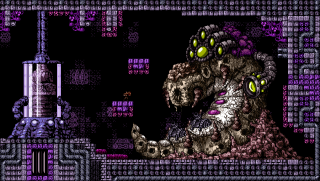

Free action is often not only facilitated by games but encouraged. For a few examples of how games might entice players to spread their wings, think of maps which branch off in all directions and show where you haven't trodden, e.g. Axiom Verge's. Or talent trees which offer up many new abilities at a time, e.g. Path of Exile's. Suppose a designer wants to guide us more forcefully. In that case, they might have us switch up our strategies by introducing enemies that effortlessly rebound our go-to attack patterns or puzzles which require new mindsets to beat. We must also take into account that variations between player experiences can arise from mistakes on the user's part. I might be zipping through The Crew aiming to jump my buggy over that river, but that doesn't mean I'll get enough height to do it. In Company of Heroes, it might look like a good idea to have my soldiers execute a pincer movement on my enemy, but I might realise afterwards that I've spread my army too thin.

Randomness and mutations in player behaviour don't just exist alongside each other but also feed into each other. We might have to change course to account for mistakes we've made, and as our behaviour changes, opponents or AI are likely to alter their choices too. These reactions between players and the game or players and other players volley back and forth, taking the session down a specific branch which often makes individual matches or plays unique. This is how every person playing a single match or level might start from the same state, but find millions of directions the game can take from there. It's the butterfly effect.

But our definition of a game doesn't always end with the rules. Rules are entirely abstract, but we live in a physical world, and so, must always find physical ways of representing the game state. Games also frequently measure our skill at manipulating physical items from controllers to balls. Additionally, many tabletop and video games aim to express visual and sometimes audio aesthetics and may convey overt narratives. Games need objects for us to operate on, to represent information, and where applicable, to deliver art and stories. For these purposes, they use balls, nets, pieces, game boards, cards, computer monitors, etc. Whether or not we define the equipment used to play the game as part of the game varies pretty arbitrarily, however.

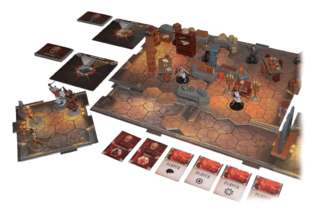

For sports and conventional card and board games, the items required to play the game are not classified as part of the game. You can buy cricket equipment or a backgammon set, but we don't call that buying cricket or buying backgammon. You can throw down a couple of euros for a deck of Hanafuda cards or a handful of polyhedral dice, but you can never buy Koi or buy D&D. You'd get weird looks trying to call this Koi equipment or a set of D&D. But you can buy the board game Gloomhaven or the card game Sushi Go! These are not abstract edicts for play which we apply to material items; we talk about the material items and the ruleset as one whole product.

Video games borrow a little from each column: we define them as encompassing audiovisual content and some equipment we use to play (e.g. Code or UI assets), but you generally don't receive everything you need to play in the box. Almost all video games rely on a machine to run: a PC, console, or mobile device, in most cases. Despite being non-negotiable play equipment, we don't consider these platforms part of the game. Still, it's through the interfacing of the physical or digital media and these appliances that the game comes to life.

In addition to providing equipment with which to play, prompting actions, and supplying audiovisual or narrative contexts for the play, video games attempt to enforce the ruleset. They keep track of states and figures, only let us make permitted moves, control the world and NPCs, and instantiate the outcomes of our actions. This is in contrast to non-video games where players or umpires try to uphold the rules, and humans simulate characters and forces beyond the audience's control. Whatever the game format, we have to say that, in general, software and people attempt enforcement of rules rather than succeed at that ruling. Almost every game has some chink the armour that lets the player skirt its laws. A referee can make a bad call, and a card shark can use sleight of hand to fake a result. Mischievous gamers may find ways to hack programs, clip through walls, or otherwise violate their spirit.

In review, it's easy to get confused about the term "games". We use it to mean sets of rules and packaged products which contain rules, art, and at least some equipment. In the case of video games, it refers to all of the above and the means for automatic enforcement of those rules. We also use "game" to mean the series of events which make up a single session of gameplay. While the former "games" can be perfectly replicated, it's exceedingly rare that games under that last definition are. The variation between game sessions is due to randomisation and inconsistencies in player behaviour, meaning that our experiences of games (under the earlier conditions) are also inconsistent.

I believe that acknowledging the difference between "games" as rulesets, content, and rule enforcement mechanisms, and "games" as gameplay sessions is important. Not least of which because it lets us understand the difference between games and other media with greater depth than "Games are like other formats but interactive". A more comprehensive explanation would say that while books, films, or TV shows consist of a pre-determined series of events, games (as in rulesets or packaged products) use rules and sometimes assets to create possibility spaces in which we can play out series of events. Thanks for reading.

Log in to comment