Hexic HD is one of the hardest puzzle games I've ever played, at least, when I'm playing to win. I realise that sounds silly because match three games are known for handling their players with the softest of grips. Their rules are so simple that even a child can learn them in seconds, and most of these games don't have a lose condition. You play against a clock or until you've filled up the screen space, and at the end, you haven't won or lost; you just have to decide whether you're happy with your score or not. But this idea that match three games must all be breezy and relaxing doesn't pass the sniff test. In every other game genre, the difficulty ranges between the serene and the merciless. So, why wouldn't it in block-swapping puzzle challenges? It's just difficult to imagine what a harder match three puzzler would look like until you play Hexic HD.

Exactly what "harder" means is always game-specific. However, it's universally true that games get more challenging when the number of advantageous or acceptable moves the player can make reduces relative to the overall set of moves available. A move could be changing the location of a piece on a board, playing a card, or basically anything that requires controller input. Designers reduce that desirable set of moves by introducing penalties, or at least, diminished rewards, for actions they do not want the player to take. Here are a couple of examples:

In a multiplayer shooter, it might be safe to stand anywhere on the map, except directly in front of an opponent. But if a player on the opposite team picked up a sniper rifle and got up to a decent vantage point, any move which leaves you standing in the open would become disadvantageous. Now, you have to be more precise in your movement; you stick to the cover.

In an RPG, you might have a variety of status effects you can unleash on enemies to damage them over time, including "burning". Then, you come across a fire elemental, and your "burning" spells only heal it. Now, you have to be more precise in your attacks to prevent your enemy's status effects giving them the metaphorical high ground.

In a match three title, moves usually involve swapping pieces. It follows that if a designer wants their match three game to demand more of the player, they could make it so that the player can't just line up any three pieces to progress. The creator could increase the difficulty by shrinking the set of desirable matches in the grid at any one time.

The most obvious direction would be to have the player match lines of more than three. However, this wouldn't change much about the audience's strategy or how they're likely to view the game. It's also not a practical modification. All match three games in which you can swap pieces handle swapping in one of two ways. In some of them, if a swap doesn't lead to a match, they reverse the switch immediately. See: Bejeweled and Candy Crush Saga. In others, player moves are persistent whether or not they clear pieces. E.g. Panel de Pon and Puzzle Pirates' Bilging puzzle.

The thing is, in match three games, the board often doesn't fall into a pattern where there are four identical pieces ready to be cleared in one move. So, if you demanded that the player matched more than three pieces in a game where only clearing moves are honoured, then it would frequently be impossible to play. If you did the same for a game where you can shift pieces even without matching any, you're going to create a puzzle where there's less of that delight of seeing pieces on the cusp of being whisked out of existence and more rotely ferrying tiles across the board. You could compensate by reducing the number of tile types in play, but this is an elaborate way to get the game back to the same ratio of valid moves to possible moves you had when you started. You're not increasing intentionality in the player's behaviour.

If we want a more transformative slant on the match three game, rather than just designing a match four game, we could try:

- Making the board out of shapes other than squares.

- Having the player compose more complex patterns than lines.

- Encouraging the player not just to match certain pieces but also avoid matching others.

- Getting the player to pay attention to all the shapes involved in a single move, not just those they're matching.

- Pushing the player to not just match any pieces but particular pieces on the screen.

Hexic is not just another block puzzler; in its Marathon Mode, it's a block puzzler that innovates and engenders intentionality in the player's actions. It commands such focus through implementing all the above ideas. It's the leaderboard for Marathon that lists the most player scores. This game type is also presented at the top of the game's main menu, effectively positioning it as the primary or default mode. From hereon, when I talk about Hexic, I'm talking about Hexic HD in Marathon Mode.

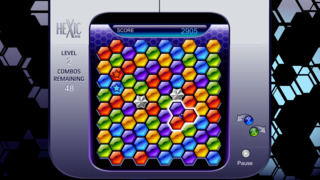

Hexic is a match three game in which the board is made up of hexagons of various colours. The player can select any three adjacent hexagons at a time, causing an axis to appear in between them. They can then rotate the selected pieces clockwise or anti-clockwise around that axis. If three hexagons of the same colour become adjacent at any point during a rotation, the rotation stops, the matching pieces disappear from the board, and the player scores some points. When blocks are erased from the grid, the hexagons above fall into the blank space they occupied. Any empty gaps at the top of the board fill with new pieces of random colours. As the player accrues points, they level up, and over the levels, the game introduces more colours to the board.

That the designers picked hexagons with a flat top and bottom is not a coincidence. The shapes the developers use for the grid can't have a pointed peak or base because other pieces on the board have to fall onto them and be supported by them. Without flat tops and bottoms to the shapes, you won't get your blocks to sit in perfect columns. The hexagonal shape also means that two other tiles can be placed alongside each piece. You couldn't do the same with, say, pentagons, heptagons, or octagons. At least, not in a grid that all uses one shape, with the polygons tiling perfectly, and the pieces filling the negative space left by clearing other pieces. We'll cover further implications of a hexagonal grid later.

To understand how Hexic motivates players to create more elaborate patterns with those polygons, we need to talk about starflowers. If the player surrounds a piece with six other identically coloured pieces, those six blocks disappear, and the tile in the centre of that pattern blooms into a "starflower". When you select a starflower, rather than being able to rotate it and two adjoining pieces, instead, you're invited to turn all six hexagons bordering it in one motion.

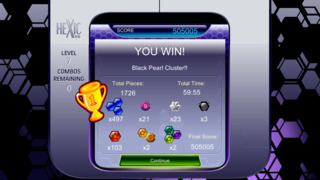

When rotating pieces via a starflower, you don't need to match them for the rotation to stop; they all cease moving after being turned one place. The player can also match three or more starflowers together for a windfall of points. If the user surrounds a single piece with six starflowers, they can create a black pearl. A black pearl can rotate only the hex above it, to the bottom left of it, and to the bottom right of it. The player can match three black pearls to end the game and add a fortune to their score. Alternatively, they can surround a piece with black pearls to complete the session with an even higher score bonus.

If you're playing the game optimally, your goal is to make and match black pearls for two reasons. Firstly, it's many times more lucrative than matching coloured pieces. Hexic has no combo system and does not place a high value on matching many pieces at once. The game decides how many points to award for a clear by taking a base value assigned to the move you've performed and multiplying it by the current level. The base pay for clearing three hexagons is 5 points, while for 4, it's 10 points. Making a starflower, however, is worth, at base, 1,000. If you can put together those starflowers to make a black pearl, that's 10,000. Matching six black pearls pays out an eye-watering 250,000 points before factoring in the level number.

In other match three games, the emphasis on combos and large clears means that the challenge of the play, and the rewards you get for overcoming that challenge, increase on a gradual curve. Players slowly learn how to match more pieces at a time and steadily get more points for doing so. By contrast, Hexic has a sizeable gap in difficulty and reward between clearing basic pieces, clearing starflowers, clearing black pearls, and so on. Remember, you don't win points for getting halfway to a special piece or matching two of them. You only get your pay packet once you've completed the whole job. It's all or nothing.

So, instead of this gentle ramp up in challenge and prizes, you get these sudden jumps. We could see that as a failure of Hexic's design; a player may feel the journey up the ladder of difficulty and reward is jerky and that their improvements in skill are not acknowledged until they hit the next tier. On the other hand, it's these stepped plateaus of hardness and score that push you to up your game. If you develop the skill to place five adjacent starflowers on the board, you're unlikely to stop there. You're going to go for the whole pearl.

The second reason to chase black pearls is that, and this is very weird for a match three game, matching black pearls is the explicit win condition. By incorporating both a hard win state and the opportunity to accrue points endlessly, the game can cater to more than one breed of player. If you don't want the pressure of worrying about whether you'll win and just want to rack up a monumental score, then Hexic has you covered. If you need the assurance and motivation of an overt goal, Hexic has that too. However, achieving that explicit goal is easier said than done. From Xbox's achievement stats, we can tell that only 0.75% of players have ever beaten the game.

Now, that difficulty comes in part because, to make these complex patterns of hexagons, we also have to respect a couple of those other earlier bullet points. We often have to care about all the pieces involved in a swap, not just the ones we're clearing. We also have to match specific sets of three rather than just any set on the board. We usually build towards a starflower by looking for areas on the grid where three or more pieces already make up part of a hexagon, and then we fill the rest of it in by shipping other pieces of the right colour across the board to it. We have to transport those pieces by looking at moves that could match three or more pieces while moving a third piece involved in the swap closer to the would-be starflower. That's much tricker than looking for any match you can make.

And there are all sorts of matches you shouldn't make if you want to complete your starflower. You can't match against the pieces you want to form the hexagon; you can't match underneath the hexagon, or the tiles will fall and misalign or match with each other; you can't clear pieces you might want to slot into that hexagon. As you build a starflower, you actually lock up a lot of the board, excluding it from use. There's an elegant quirk of the design where the ruleset that makes matching pieces so desirable as a casual player also makes many of those clears something you want to avoid as a higher-level competitor. Can you see how the design is restricting the set of valid moves and asking for more specific inputs on the part of the player?

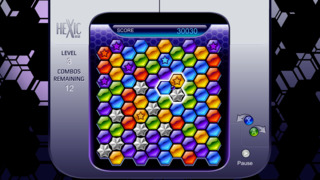

Once you have a few starflowers on the board, you gain more agency over your domain. Ideally, you build a starflower transport network where you can relocate a hexagon from one side of the board to the other by passing it from starflower to starflower. However, in our galaxy of starflowers, new challenges arise. You don't want the stars to drop into the bottommost slots on the board, or they lose their powers and get very finicky to pick back out. Additionally, because starflowers allow you to rotate more pieces than you could in a standard turn, you have to think more carefully about the moves you make with them. A regular swap rotates three tiles, and the hexagons it controls are checked against a total of nine surrounding hexagons per move. A starflower rotates six pieces, and the hexagons it controls are checked against a total of twelve pieces. All of those extra checks could lead to one of those undesirable matches we talked about earlier.

Losing the pieces that could be about to make up a starflower is a blow, but once you have three starflowers on the board, you risk a real kick in the pants: accidentally matching all of them and obliterating them in one move. When you see your work go up in flames like that, it becomes obvious that Hexic is no longer a friendly entertainer and has become a punishing drill sergeant. Again, we can see a fascinating self-regulating quality to the rules here: the more starflowers you introduce to the board, the easier it is to accidentally engineer a collision between them.

You can reduce the prevalence of starflowers by vitrifying them into black pearls. Unfortunately, if you get into the late game where there are many different colours on screen, and you don't have starflowers to micromanage it, you will end up with a cluttered, frozen board in which constructive matches are few and far between. Starflowers are also beyond useful for moving other starflowers, and so, are must-haves for when it's time to form a black pearl. If you have two starflowers in the orbit of each other, you can "walk" them across the board by alternately rotating each of them.

Playing Hexic is like playing any game with some depth, in that you start scrawling a mental notepad of the dynamics that form between pieces and a shortlist of good practices that take those dynamics into account. For example, sometimes, you have to erase a set of tiles that almost make a starflower to free up other pieces blocked from doing the same job. You also can't really fill in a hexagon from below because, to move pieces, you need to match pieces, and if you start matching underneath a hexagon, it'll fall apart. Attempting to build a hexagon too near the top of the board often results in an awkward situation where you have little space to work with above them, and so, unless starflowers permit, you want to build them in the middle or bottom of the board.

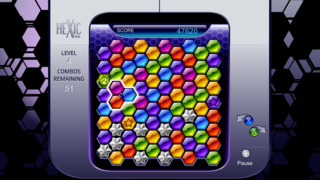

While we've talked about ruts you dig yourself into, we've yet to talk about explicit fail states: the element of the game that would mean users can't just play a session endlessly, trying to correct mistakes. In Marathon Mode, it's bombs that the player must watch out for. These are coloured pieces that drop into the board and will "explode" in a certain number of moves if you do not match them against at least two pieces of the same colour. A detonation means game over.

Bombs are another way that the game pushes players to focus on matching specific sets of three and refrain from breaking certain patterns. If the player wants to survive, they must match against the bomb, refrain from any moves that might jostle the bomb into an inopportune position, and mustn't delete blocks they might match this powder keg against. Again, starflowers help immensely with connecting bombs to pieces of the same colour. As different bombs and near-hexagons appear and disappear from the board, the player's focus is pulled towards and away from specific spots in the play area.

The problem for the Hexic HD player is not just that the individual acts of making a starflower, making a black pearl, or matching black pearls are strenuous, but also that they must climb through each of these tasks, in succession, to win. And if they stumble at one of the steps, they must start again from the bottom of the mountain. When you get a special piece in most match three games, you burn that power-up, and that's the end of the story. In Hexic HD, you must make a specific pattern out of six coloured pieces, and do that five more times, and then make all of the power-ups you get from those processes into a new hexagon, and repeat that process twice, and then match the power-ups from that last series of alignments, if you want to win. Completing all those steps without a bomb going off is next-level demanding. And not all that fair either.

Once you get skilled enough, it often feels like you lose sessions of Hexic not because you made dumb choices but because the board fell in the wrong pattern. I know in games with a dash of randomness, it's easy to blame the RNG when you fail, but it is a demonstrable burden in Hexic's case. In a match three game with a square-based board, each piece is checked against up to four adjacent tiles to see if it matches. In Hexic's hexagonal board, the engine compares each piece against up to six surrounding pieces.

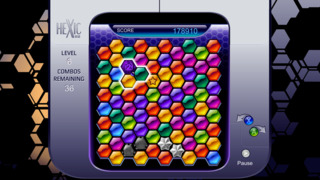

On lower levels, there are only five different colours on the board, so one match will often set off a long combos of clears. That's great if you're playing casually. However, if you're being more strategic about your play, and trying to put together starflowers, sometimes the pieces you're using to compose them can be wiped off the board because the wrong tiles randomly fell onto them. Still, the early game is considerably more forgiving than the late game, where you'll encounter the opposite problem. After level 5, Hexic uses seven different colours, and as covered, much of the board also gets locked up by special pieces. That means fewer opportunities to match pieces per screen than you get in other match three games, a huge issue when you need to defuse bombs quickly. And the higher the level, the shorter the bomb timer.

Let's compare Hexic to some other titles representative of the genre. Panel de Pon only uses four colours, while Candy Crush Saga uses four to five, although Candy Crush often blocks parts of the board with barrier tiles you must break. Bejeweled uses seven piece types but doesn't have blocking pieces, and all three games liberally introduce power-ups or bonuses to make clearing pieces easier. Hexic doesn't introduce many bonus pieces, and when it does, you often don't want to use them. Reckless actions like banishing a colour from the board can ruin your intricately organised patterns.

You might think that the hexagonal grid gets you out of that jam, but for any one hexagon on the board, your rotation will only check it against up to nine other pieces. For comparison, you can test squares in other match threes against up to eight. So, 50% more sides for the tiles doesn't mean 50% more opportunities to clear. And at the same time that Hexic makes the board less cooperative, it's demanding greater matching skills by pushing you to create more elaborate patterns than you have to in another game of its class. That might not be worthy criticism if making the wrong matches didn't come with weighty consequences or if we could tell what pieces will get dropped onto the screen, but it does, and we can't. The end result is that you can always make clears on the grid, but they're not necessarily the clears you need.

It would be easy to analyse Hexic's problem as a contradiction between its themes of control and chance. To say that the game is doomed to fail because, on the one hand, it's randomly generating pieces, yet, on the other, it's trying to have you operate with precision and specificity. Still, there are plenty of other games which capably incorporate both of those ideas. Sometimes you get a bad board in Bejeweled Blitz, but Blitz matches only last two minutes, and no consequences from one session carry over into another, so it's not like there's much at stake if the RNG dunks on you.

There are plenty of card games where the shuffled deck means that our power level at any one time is mostly random, where stakes can be high, and where losses are persistent. For example, in Texas Hold 'em, we have no control over, or foreknowledge of, the hand we'll get, and losing one hand affects our resources moving ahead. But then, the trick with a game like Texas Hold 'em is that while all hands are random, it's the player who has the final decision about how or if to play a hand. They don't have to stake anything on it if they don't want to, and the cards in play are reset every turn. In a board game like Ticket to Ride, the cards you get are random, your hand is not reset, consequences do carry between turns, and there is something at stake in every turn. Still, you are not stuck with the hand you draw; you add to it throughout the game with no maximum limit, and personal consequences that carry between turns are mostly positive. You can't draw a card that will disadvantage you.

In Hexic, there is often a lot at stake. If you're trying to match three black pearls, a game can realistically last you forty minutes, and a fractional slip up can be the difference between success and failure. So, there is a lot of investment from minute to minute. There are almost no ways to refresh your largely random board, the consequences of bad RNG are relatively long-term, and it's not like you can add to that board endlessly like you can with your hand in Ticket to Ride. If you've got the wrong pieces in the wrong places, your options to unjam them are limited. You can't bet low if things aren't going your way, and sometimes the game makes decisions for you, like just clearing out your pieces in the early levels. So, you end up with this trifecta of characteristics that often appear in games that feel unfair:

- Unavoidably high stakes.

- A lofty bar for success.

- Limited control over that success.

That inevitably creates situations that put the player on a losing course, with a sizeable cost for that loss, and no ability to divert.

Let's conclude. For our purposes, Hexic HD serves as a guide on making a game harder by containing a smaller set of ideal moves relative to other match three games. Through that change-up, it encourages more specific action on the player's part. However, modifying only some game elements while trying to achieve a difficulty bump can be dangerous. Designers will have probably created the whole game format with implicit ideas about how each mechanic functions that may not suit the concepts you're introducing.

While Hexic HD implements a limited collection of desirable moves, it retains an aspect of other match three games in which the pieces introduced to the player are random. The contradictions between these old and new design elements spark a conflict between what the game demands of players and what it allows them to do. Hexic asks its audience to maintain tight control over the current game state, even while changing that state outside of the player's control. Thanks for reading.

Log in to comment