Fifth Gen Recap: Blocky Magic

By alianger 0 Comments

The fifth console generation. PS1, N64, Voodoo graphics on PC and now insanely expensive 2D games for the Saturn. This was a time when shamelessly clunky 3D models were put on the front of magazines and game boxes while young people and games journalists tried to forget that 2D was still a thing. A time when you could walk into a store, pick a few random games and end up discovering about as many new genres. Some of them could also be mistaken for movies. Spanning from 1993 to about 2002, so about a decade, the period brought significant technological advancements, cultural shifts and creativity to the gaming industry. In this massive (for me) blog post, I'll delve into the key features and trends of the fifth console generation, highlighting its impact on the gaming landscape.

Demo discs: This generation saw the rise of demo discs, which were often included in gaming magazines (such as PSM or PC Gamer) or bundled with consoles. These discs allowed players to sample upcoming games and demos, creating giddy anticipation and hyping up new releases. In the case of the PS1, they would also include what are called Net Yaroze games, homebrew games that were that period's equivalent of the next generation's indie game scene and would sometimes be complete games given away for free.

Online Multiplayer Games on PC (RTS, FPS and ARPG): This generation brought multiplayer experiences to the forefront for PC players. Games like Command & Conquer, Warcraft 2, Red Alert, Starcraft, Quake 1-2, Team Fortress, Half-Life, Unreal Tournament and Diablo allowed players to compete or cooperate with others from around the world, adding a new layer of depth and challenge to the gameplay. In addition to the multiplayer in-game, the chat rooms and online communities dedicated to these games led to an environment where people would start clans (now esports teams), exchange strategies and tips, and even semi-socialize. This in turn led to many new terms among players that are still in use today, such as fragging, camping, turtling, buffing and nerfing, player killing (PKing, Diablo) and rushing, to name a few.

3D Dominance, CD audio and Pre-rendered Backgrounds: The fifth generation marked a shift towards 3D graphics and gameplay, with many games adopting both 3D environments, controls and character models. During this era, it was fairly common to see both magazines and players dismiss games simply for being 2D. Additionally, CD-based media became the norm, allowing for higher quality soundtracks, sound effects, and just a lot more content in games. MIDI audio also improved, coming closer to the quality of average CD audio recordings. Far from all developers switched directly to creating fully 3D games however. Final Fantasy 7-9, Resident Evil 1-3, Grim Fandango and Blade Runner are some notable games that employed pre-rendered backgrounds, blending detailed 2D artwork (often made up of 3D artwork stills with some animated elements) with real-time 3D character models. This led to a distinct style of both aesthetics and gameplay that, while divisive, is still loved by many.

Decline of Arcades and Arcade-style Games: The popularity of home consoles and console-style games led to a decline in traditional arcades (with some exceptions in the east such as Japan and South Korea). Most arcade-style games transitioned more smoothly to console platforms from this period onwards, thanks to the advancements in graphics on home systems, and players started expecting such ports to have additional features like story or career modes and extra characters. With multiplayer becoming more accessible on some platforms, the convenience of playing with friends or opponents without leaving the house further reduced the appeal of arcades.

Twin-stick and Free Look 3D Games: Towards the end of the fifth generation, twin-stick controls became the standard for console games in 3D. This control scheme, innovated in 2D by the games Western Gun/Gun Fight (1975) and Space Dungeon (1981), then later on in 3D by Descent on PS1 (which supported the dual analog flight stick controller), allowed players to have more precise control over camera movement and character actions. It was popularized by later PS1 games like Ape Escape, Resident Evil 3, Tomb Raider 3, Mega Man Legends 2 and Ace Combat 3, and to some degree by the Nintendo 64 in that some games (Turok being one of the better examples) used the c-buttons or d-pad as a makeshift second stick. GoldenEye 007 for N64 actually did feature twin-stick controls - the problem was that it required two controllers to do it, limiting the multiplayer aspect of the game. Free Look or mouselook, was first introduced by the FPS games Marathon (MAC, 1994) and Terminator: Future Shock (PC, 1995), however the game that eventually popularized the now standard WASD keys for movement and mouse for looking around setup was Quake (PC, 1996), for which the online MP community would change the default arrow keys for movement setup, to WASD as the preferred setup.

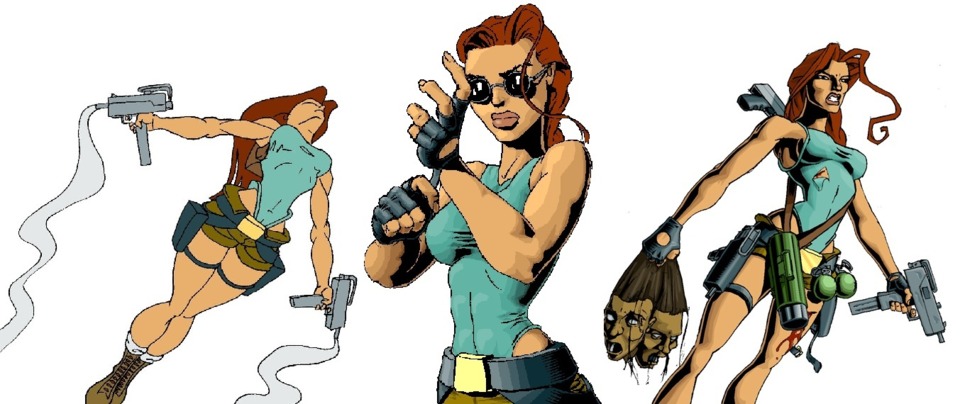

Mainstream Female and Genderless Protagonists: The fifth generation introduced mainstream characters that broke stereotypes. Lara Croft from Tomb Raider became an iconic female protagonist known not just for her looks (or being essentially anonymous like Samus, bless her soul) but for her personality, intelligence, and adventuring skills. Her popularity paved the way for more diverse representations of female leads in subsequent generations. Similarly, Nights, from the game Nights into Dreams, was intentionally designed as a genderless protagonist for Sega's next flagship game for their new console. A game that captivated players with its unique concept and gameplay. Nights as a character challenged preconceptions about video game characters, while metaphorically inviting players via the cypher-like boy and girl player avatars to be the best version of themselves rather than what people around them expect of them.

New (or Evolved) Genres: The fifth generation was in many ways like a new beginning for games as a whole, and man was I there for it as a teenager who had been playing the 8-bit and 16-bit consoles for quite a few years by then. The changes came incredibly fast and it seemed like several times per year there would be an entirely new kind of game waiting to be played. Let's go over the completely new as well as the revived and evolved genres of this era.

RTS Games: Real-time strategy (RTS) games flourished during this generation. Titles like Command & Conquer, Red Alert, Warcraft 2 and Starcraft introduced players to base building, resource management, scouting and commanding armies in real-time battles, now with online and LAN functionality. Not long into the generation, Bullfrog also managed to inject their usual creativity into the genre with the cult classics Dungeon Keeper and Populous: The Beginning.

Trainer RPGs: This generation saw the rise of trainer RPGs, where players could capture and train creatures to fight in games otherwise similar to Japanese RPGs of the time. Games like Pokémon (influenced by the Ultraman TV show Ultra Seven and possibly the games Digital Devil Monogatari: Megami Tensei, Barcode Battler and/or Lufia II), Digimon, and Dragon Quest Monsters offered players the ability to collect, raise, and battle with a wide variety of creatures.

JRPGs in the West: Japanese RPGs gained significant popularity during this era, finally breaking the mainstream outside of Japan. These games featured anime-style visuals, turn-based combat, a focus on storytelling, character-driven narratives, and predefined characters and main questlines. By now these games also often included extensive cutscenes that simulated a cinematic experience. Speaking of which, cutscene heavy games became popular in other genres as well with some notable examples being Metal Gear Solid, Starcraft, Silent Hill, Grim Fandango, Soul Reaver, Resident Evil 2 and Spider-Man. With the CD format becoming the new standard, translations being taken more seriously by localizers, and anime aesthetics becoming more popular in the west, Japanese developers now had the means to better realize their visions and to have them not get butchered on their way to the west.

Mainstream Survival Horror: Survival Horror games became mainstream during this generation, after being pioneered in previous ones by games like Alone in the Dark and (in Japan) Clock Tower and Sweet Home. Titles like Resident Evil, Silent Hill, System Shock 2 and Dino Crisis introduced players to atmospheric horror, challenging gameplay, and engaging narratives.

Rhythm Games: The fifth generation brought the popularity of Rhythm games, where players followed musical cues to score points and progress to the next level and song. Games like Dance Dance Revolution, Parappa the Rapper, and Beatmania created a new genre that blended music and gameplay, where such elements had been relegated to mini-games in a few previous games such as Toejam & Earl 2.

Revival of Stealth Action Games: Stealth Action games made a comeback after a hiatus in the previous generation (besides maybe Covert Action (1990) which is more of a hybrid game). Titles like Metal Gear Solid, Tenchu and Thief, all released in 1998 reintroduced stealth mechanics to 3D gaming. They became highly influential, finally establishing the term as its own game genre to the average player.

3D Collectathon Platformers: The introduction of 3D graphics and mainstream series like Mario adopting the gameplay style led to a huge rise in the popularity of collectathon platformers. These are games where players explore open-ended levels, usually accessed via a hub world, to collect various items required for unlocking the next set of levels. Games like Super Mario 64, Banjo-Kazooie, and Spyro the Dragon exemplified this genre.

Diablo-like ARPGs: The fifth generation saw the emergence of Action RPGs influenced by the success of Diablo, itself a graphical, real-time take on Rogue and other dungeon crawler RPGs with a then new for the genre online multiplayer feature. Games like Dark Stone, Nox, and Throne of Darkness offered similar gameplay mechanics, although Diablo remained the most popular and influential in the genre.

Life Simulation and Virtual Pet Games: The popularity of virtual pet games, a subgenre of life sim games, soared during this era. Games like Dogz and Catz (1995/1996), Tamagotchi (1996), Digimon (the portable 1997 version) and "Hey You, Pikachu!" allowed players to care for and interact with virtual pets, nurturing them and forming a bond. Life sim games themselves experienced significant success a few years later during the transition from the fifth to sixth generation, with games like The Sims, Animal Crossing, Monster Rancher, and Harvest Moon captivating players with their immersive virtual worlds and activities.

Arena Fighting: The fifth generation saw the emergence of arena fighting games. Titles like Virtual On and Super Smash Bros. provided fast-paced, multiplayer combat experiences in dynamic arenas, where the latter also featured a twist in that the goal was to knock the player out of the ring like in a(n over the top version of a) Sumo match.

Western RPG Revival: Western RPGs for PC gained prominence in the latter half of the fifth generation. Games such as Baldur's Gate, Fallout, Planescape: Torment and The Elder Scrolls II: Daggerfall showcased deep narratives, expansive and open-ended worlds, and player choice affecting story outcomes and character relations. I'll discuss most of these in more detail below.

Pioneering Open World and MMO Games: Several titles from this generation walked so that future games in these two genres could run. Grand Theft Auto 1-2 and Ultima Online, while not among the most commercially successful games at the time, were influential titles that established new standards and gameplay mechanics for open world and MMO games, respectively. The aforementioned WRPGs also evolved and influenced these genres, particularly the Open World genre.

Grand Theft Auto 1-2 (1997/1999, by DMA Design) introduced players to expansive urban city levels where they could freely explore and engage in various unwholesome activities, usually leading to them being chased by the police (then getting back at it after avoiding them for a few minutes). Or they could take on missions - should they fail, a level/city keeps going but they would tend to get locked out of certain other missions. Or if playing on PC they could team up in a LAN game and wreak as much havoc as possible until finally being taken out by the police and military. In GTA 2, several rival gangs to work for were introduced along with a diplomacy system that shaped one's path through the mission structure of each level. Yes, these games put their own spin on the concept of open-world gameplay. They're essentially a set of smaller scale open worlds unlocked in a linear fashion, and they opt to not have player characters gain any permanent stat boosts, abilities or tools over the course of the game.

Ultima Online (1997, by Origin Systems) became one of the earliest successful MMOs. It created a vast, seamless and persistent virtual world (4km on a side) where 2500+ players could interact simultaneously, wearing equipment that showed on their player avatars. Ultima Online revolutionized the gaming landscape by introducing players to a shared online experience where they could forge alliances, engage in unrestricted player vs player combat, participate in craft-based and player-driven economies, and take on quests together. The game would go on to inspire Everquest, Runescape, Wurm Online, Eve Online and possibly Second Life.

Baldur's Gate (1998, by BioWare) introduced players to a richly detailed and expansive open world filled with intricate quests, memorable characters, and for its time deep storytelling. A world where players could freely explore with up to six characters and make meaningful choices (although none that substantially affect the main quest as there is only one ending until the sequel's expansion), either controlling the whole party on their own or with others. The game's influence can be seen in games like Neverwinter Nights 1-2, Planescape: Torment, Pillars of Eternity, Tyranny, Divinity: Original Sin and Pathfinder: Kingmaker. Furthermore, the game's isometric perspective (something it shares with Fallout) became defining of the genre for years to come.

Fallout (1997, by Interplay Entertainment) brought a post-apocalyptic setting to the open-world genre, one that greatly expanded on the one created for Wasteland about a decade beforehand. With its branching narratives leading to multiple endings, open-ended gameplay and moral dilemmas, Fallout set a new standard for player agency and choice-based storytelling. Fallout's impact can be seen in the subsequent entries of the series and other open-world games such as Deus Ex (technically semi-open world), Arcanum, Wasteland 2, Underrail and Atom RPG, and some sources state that its perk system inspired World of Warcraft.

The Elder Scrolls II: Daggerfall (1996, by Bethesda Softworks) was a groundbreaking title that pushed the boundaries of open-world design. It presented players with an enormous, procedurally generated world that spanned tens of thousands of square miles, dwarfing its predecessor. Daggerfall's vast world with its numerous towns, dungeons, and factions, showcased the potential for exploration and discovery in open-world games as well as the state of randomly generated content at the time. The game's ambitious scope (it featured 18 character classes, spellcrafting, faction diplomacy, branching quest paths and multiple endings) and sheer scale laid the groundwork for future entries in The Elder Scrolls series. Furthermore, its vast and mostly seamless 3D world that players could be content to just explore and spend time in rather than try to finish the main quest in probably inspired later open-world games that otherwise don't really play like it - Daggerfall still stands out due to its combat system and focus on dungeon crawling.

Collectively, these games expanded the possibilities of open-world games. They demonstrated the power of player agency, the freedom to explore dynamic and interactive virtual worlds, and interactive storytelling. They inspired following generations of game developers, leaving an unforgettable mark on the gaming landscape.

Jackass and Tom Green-style Ads: Advertising during this generation often featured outrageous and humorous content, influencing and influenced by shows like Jackass (itself inspired by '90s skateboarding culture) and personalities like Tom Green. Game commercials embraced this style to capture attention and appeal to a target audience of teenagers and young adults. The influence of Jackass and Tom Green-style content on game advertising was evident in the use of shock value, immature humor, attitude, stunts, and unexpected scenarios to capture attention and resonate with a presumed target audience of teenagers and young adults. Sure, while an edgy attitude and creepy or gross elements had been successfully used by Sega (and sometimes Nintendo as well, see the Yoshi's Island or Gameboy Camera ads) during the previous generation, during this era there was also a DIY vibe to many of the ads, with purposely amateurish filming and a seemingly low budget. This was perhaps best exemplified by the Cash Bandicoot commercials, which resemble the aforementioned influences pretty closely. By aligning with these influences, game advertisers aimed to make their products stand out in a crowded market and create a memorable impression on potential consumers.

Early Browser Games: The advent of the internet of course also led to games accessed through and played while connected to it, some of which became very popular during this era. A few are still being played today even, albeit in updated form. Titles such as Subspace (1997), Archmage (1998), Neopets (1999), Runescape (2001) and Bejeweled (2001) offered accessible and fun gaming experiences for anyone with a decent internet connection. The spread of the internet, however, was in its early days and going relatively slowly - by 1997 only about 20% of North American households had access and about 50% were still without by 2007.

No Backwards Compatibility on Console: Unlike in the previous and most later generations, none of the fifth generation consoles offered backwards compatibility options. Despite early rumours about that very visible cartridge slot on the Saturn and it seemingly making sense given the Mega Drive/Genesis's huge popularity, it ended up being used only for RAM expansions instead. This was a step back from the Master System and Game Boy support for the MD/GEN and SNES, respectively, although those did require separate add-on hardware. Players who didn't keep or never had those consoles would instead have to pray for ports, which were rare in the fifth generation, or wait for the GBA to arrive. PCs, on the other hand, did things differently. They had started receiving decent emulators of previous generations' consoles by the late '90s, which would quickly spread far and wide through Usenet and Geocities pages on the internet along with dumps of the game ROMs. Playable contemporary console games even became (sort of) a reality towards the end of the generation, with the controversial Bleem! emulator being a rare commercial example.

From Doom clones to... Half-likes?: During this generation, mainstream FPS games transitioned from the - usually solitary - shooting tons of bad guys while exploring abstract mazes in games like Doom and Star Wars: Dark Forces (reinterpreted in full 3D in Quake, which also added some platforming to the mix), to what were essentially Action Adventure (sometimes ARPG) games in first-person view. Half-Life and System Shock 2 were two games held in high regard that introduced narrative-driven experiences taking place in mostly continuous game worlds, with various scripted events, basic puzzles and (in Half-Life's case) NPC interaction. Among the transitional games, some of the most noteworthy are Strife (which arguably is more of a traditional Action Adventure game than either Half-Life or System Shock 2, however it is a Build engine game), GoldenEye 007, Unreal, Quake 2, Dark Forces 2, Turok and Powerslave/Exhumed. System Shock (1994) should also be mentioned here as an early example, however its unusual control scheme based on Ultima Underworld separated it further from FPS games as we know them today.

Failed 2D to 3D transitions: Not all developers were well prepared for the great switch back in the mid-late '90s. Consequently, some games struggled to make a successful transition from 2D to 3D graphics during this generation. Titles like Bubsy 3D, Fade to Black (the sequel to Flashback), Earthworm Jim 3D, Contra: Legacy of War, and Castlevania 64 didn't do as well at adapting their gameplay and visual styles to the new dimension as people expected, something that most of them never really recovered from in terms of 3D sequels.

Expansions on PC: Finishing off this list are the various expansions for PC games during this era, the popularity of which continued in the fifth generation and extended into the next. PC games like Baldur's Gate (Tales of the Sword Coast), Warcraft 2 (Beyond the Dark Portal), Starcraft (Brood War), GTA (London), Half-Life (Opposing Force) and Diablo (Hellfire) provided additional content and extended the gameplay experience for players that couldn't get enough of them.

---

In conclusion, the fifth console generation was an incredible era characterized by frequent, significant change that had a lasting impact on gaming history. It saw the rise of demo discs, online multiplayer experiences, 3D and console-style games dominance, CD audio and the format's loosening of space constraints, and revolutionizing control schemes. It also introduced various new genres (including RTSs, trainer RPGs, rhythm games, 3D open-world games, MMOs, 3D collectathon platformers, and Diablo-like action RPGs), challenged some stereotypes, and pioneered groundbreaking gameplay mechanics.

Now, I know what some of you are thinking, and you're not completely wrong. "But the tank controls, the sub 20 FPS, the pop-in! The lack of actual faces on the models! Who look like legos by the way. This era sucked!" Nowadays, some of the more experimental 3D games from this era aren't quite as magical, I agree (although I still dig faceless models, call me weird). However, many of the games actually hold up well, and several that don't can be improved upon with mods and emulation features that are just a few clicks away. The spirit and aesthetics of the era also live on in projects like Bloodborne PS1, Hoolopee's demake trailers, and a new(ish) wave of indie games paying tribute to it. If there's a best time to revisit this era and truly indulge in it, it's probably now. So let's mosey. Thanks for reading!

Log in to comment