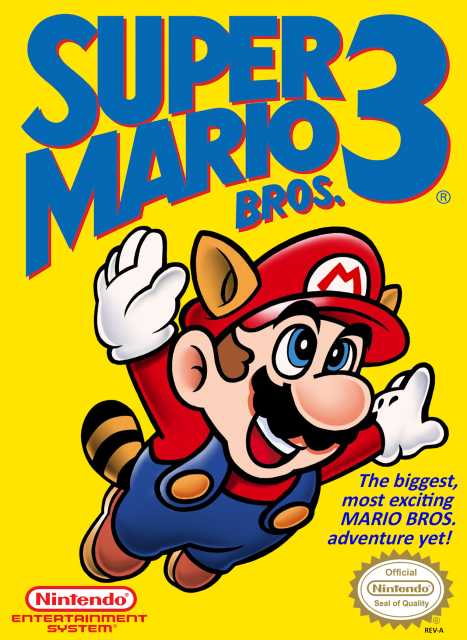

But then there's this game, which I think looms over everything else in its year. This isn't just a sequel, it's a kind of revolution. It doesn't fulfill promises from the previous games, it comes up with its own promises and carries through on them in the same instant.

It's an improvement not just in scope, or features; but in aesthetics, concept, and narrative. The world map itself is such a wonderful staple. The notion isn't anything new for the form, but how it's implemented is fantastic. It visually communicates longstanding shorthand in platformer game design; shortcuts and bonus stages are given spacial context, for example. Moreover, it's a lively, pliable world map. Items found can influence the world and Mario's place in it, from creating shortcuts by changing the geography of the map itself, or by flying over levels entirely. All the while trees bob, the on-map enemies amble about, and the the castle calls for help.

The game operates on the same rules that the first Super Mario Bros. does, but with every concept pushed about as far as it can go within its given framework. Levels often require more than moving right and timing jumps, with some asking for vertical traversal and others auto-scrolling. Resourcefulness, and use of stored powerups play a part in completion, but also help to smooth over what might be considered flaws in the first game. The plodding underwater sections can be helped with the frog suit, precision long-jumping can be helped with the raccoon tail, and if those hammer bros pissed you off you can can even use their annoying powers for yourself. Super Mario Bros. 3 isn't just some formulated improvement either, it impresses in wild, memorable, and flamboyant new ways. A sun that pursues the player, a big green boot you can high-jack and stomp about in, hell, an entire world that's way bigger than you are. Part of why I love this game is for how nutty and unhinged the whole thing is; how it's able to stick to the spirit of the series while also transforming it so much.

Though ostensibly being mid-life for the NES, there weren't many games for the system that looked better than this one. The color palette is generally lighter, allowing for greater contrast when the darker stages roll around, and a greater emphasis is put into perspective, with shading, edges that appear rounded, and drop shadows all playing really well despite the limitations. What's most impressive to me is that the game flirts with artifice. Parts of the stage look to be held up by screws or constructed by wood, some platforms have gears and paths cut in the sky for their movement, the floor of a stage sometimes appears to slope towards the screen---like the down stage at a theater. All the while the game is opened and closed with curtains. This all helps to contextualize the game's story, but also seems to ask the player to notice the craft, the art, of the game itself.

My single favorite moment of the game is the ending, or at least a part of it. I don't mean the Bowser fight, but what comes immediately after it. Peach is shown crying in a room with dark blue tile walls. Mario enters and stands in the doorway. A beat afterwards, the tile walls shift color to pink, and Peach turns around right after. She doesn't hear him or see him, but notices his presence. Her emotional shift and realization is reflected in the environment. It's an awesome bit of storytelling, something that speaks louder than any grand gesture or piece of dialogue could.