Why I was disappointed with Mortal Kombat X

By xerseslives 14 Comments

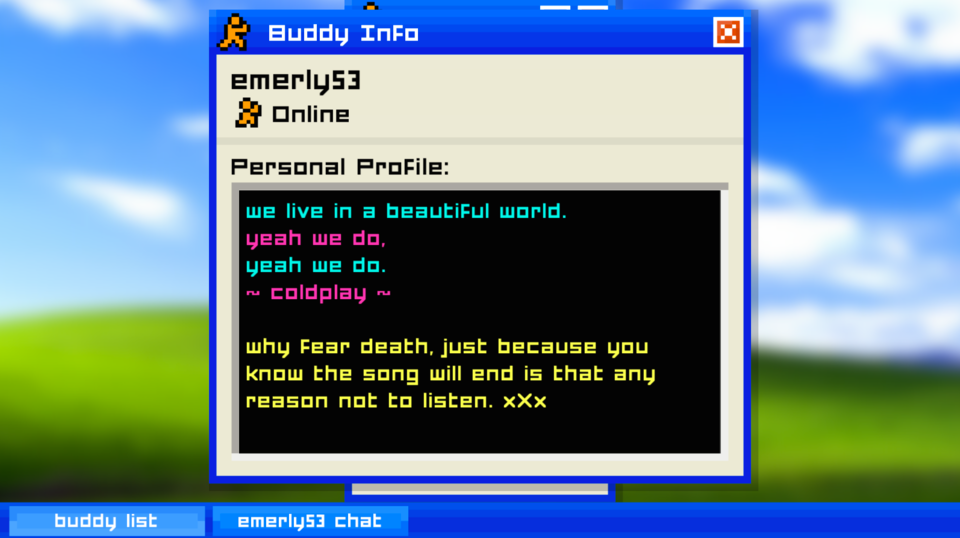

I think an important part of growing up is that first time you consume a piece of media that you know was intended for someone much older than you, be it a gruesome horror movie, vulgar song lyrics, or even, gasp, a naked person on late night cable. When you're young, so much time and effort is spent trying to shield and protect you from such things that are so omnipresent in our adult lives that most of us consider that the moment when we lost our "innocence".

Like most kids here in the States, I was exposed to violence long before sex was even a concept in my young mind, and Mortal Kombat was my gateway drug to such corruption.

It feels strange sitting here, trying to formulate my thoughts on MKX only days after going off about how much I hate nostalgia, since I'm tempted to cite my earliest arcade memory; getting destroyed in Mortal Kombat 2 against a Kung Lao that decided to further taunt me with a friendship. I'll never forget the melodramatic whining that followed, as I kept repeating "I lost" out loud in disbelief, somehow shocked that I wasn't the greatest video game player in the world at the age of 10.

Long after the desire to redeem myself for such an embarrassment quelled, I stuck with MK because I was drawn to the universe and odd characters within. Even if it was really nothing but a amalgamation of cheesy kung fu and action movie tropes, the story stuck with me, and more importantly, it grew with me. Street Fighter, despite being miles better as a pure game, was static. No matter how many games were released, they seemed to all take place within the same 2 year timeline. Chun Li never grew old, never truly got her revenge. She became a comic book character, a symbol that never owned more than one iconic outfit, unchanged through my adolescence and far into my adult life.

Mortal Kombat was different; relationships changed, characters died. Sure, they'd come back, but maybe they'd return as a different person, or on a different side. Make no mistake, Mortal Kombat was an initial success almost entirely due to timing and marketing. Everyone wanted to see the ultra-violent fighting game that sent politicians into a tizzy, but long after that novelty wore off, people stayed for those crazy characters that looked straight out of heavy metal album covers.

Sadly, I don't think the people responsible for their creation ever really wanted it that way. At no point is that more obvious than with Mortal Kombat X.

It's bittersweet really, since MKX is easily the best playing game in the series by miles and the introduction of the variation system is something they can iterate on for years, but MK spent the better part of two decades before that living as a gimmick, outside the realm of legitimate fighting games. The only thing holding it together was that universe; those stories. Fans willingly played bad games to see the fates of their favorite characters, but it eventually became too bloated, too aimless, and those same people felt isolated.

Post-reboot, with a sense that everything was getting cleaned up and the gameplay was finally starting to match the appeal of the narrative, I was more excited for MKX than any other game in a long time. The marketing cycle was exhausting, often going months at a time without any new information or character reveals. This was going to be the game where it finally all came together. It was to be darker, more serious, a changing of the guard, a chance to retell stories that had been such missteps in the past, a new beginning for characters that had been seen as underdeveloped jokes before. As we got closer and closer to release, however, I started question exactly what was being made. I started to wonder if the series that I'd watched grow with me had finally stop moving at the same speed, destined to be left behind.

And here I am, trying to articulate why the best playing and best selling game in the Mortal Kombat franchise disappointed me. I'd like to think that I've been pretty good at avoiding the internet trap of thinking that I have some degree of ownership in the media that I'm a fan of, as if the developers were entitled to cater to my tastes. The whole beauty of creating something is that it can be shaped in whatever way the author desires, but I can't help but look at MKX and lament just how safe it all is, from the roster choices, to the uninspired story, to the pandering inclusion of various guest characters. For a franchise that was built on being this aggressive, in-your-face filth that was supposed to upset your parents, it's now blasé.

It would be easy to say that Boon and the gang simply "sold out" once under the banner of Warner Brothers, and there is certainly evidence to suggest how much they tampered with the final product, but I think the real answer is much simpler than that: Mortal Kombat was created by a crew of guys that liked kung fu and thought ninjas fighting arm-blade men were cool, then it became the biggest game in the world and they never really knew how to handle that. They never thought people would grow to care as much as they did. It explains why they likely don't see how disrespectful they can be to their own universe and characters, often publicly announcing how much they regret or even despise these creations, expecting the fanbase to also be in on the joke, seemingly unaware that same fanbase is the one calling for their returns. It's a WWE level of tone deaf made even more evident by the recent reveal of the second Kombat Pack. It's a far bigger issue than "the characters I want didn't make the game". It's indicative of a bigger issue; the sign that Netherrealm has played the same pat hand one too many times, either blissfully ignorant or blissfully secure in the fact that MK sells on name alone at this point.

As someone that's stuck it out this long, waiting for something to click, I have to stop and wonder if this is the best we're ever going to get, if years from now, Mortal Kombat will be so distanced from that past as a piece of 90s counterculture and just generally regarded as nothing more than a competent fighting game with a nonsense story. And Jax is in it again for some reason.

Maybe we've already reached that point and I'm the ignorant one, unable to let go of what I wanted MK to be in light of what it's become, letting myself fall victim to those same nostalgic trappings that I've dedicated so much time to rejecting. When the next Mortal Kombat game is on the horizon, it's certainly something I'll need to think about.

Log in to comment