Top 5 pizza toppings in Shelmerston! You won't BELIEVE #3!!! :O

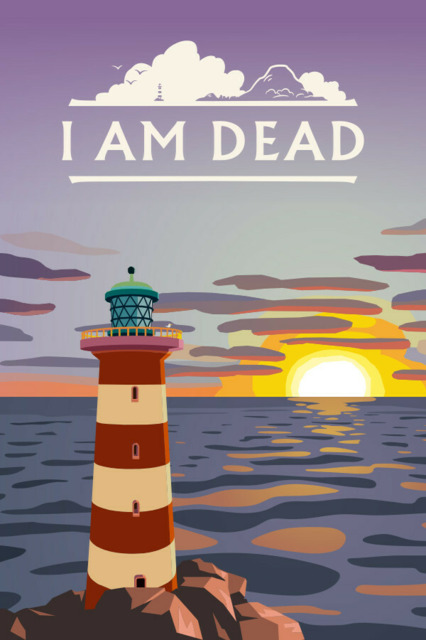

On a beach out by Shelmerston’s lighthouse, lit softly by the rising sun, there sits a memorial dedicated to the island’s late museum curator. Evidently, he was a man worth remembering, whose contributions to the small island warranted a permanent addition to the landscape. It reads:

In loving memory of

Morris Lupton

1957 - 2019

Curator of Shelmerston Museum.

He collected the stories of this place.

This small obituary speaks volumes about Morris, despite not saying much at all. A lifelong resident of Shelmerston, he dedicated his life to finding, documenting, and displaying pieces of the island’s history, from small local legends to big bold newspaper headline discoveries. Shelmerston museum wasn’t strictly historical so much as it was biographical, a living and growing record of the island’s life itself, where a blow-up camel float ring is as important to understanding it as a thousands-year old mummified indiginous tribesperson. Morris Lupton understood this, the innate value of the person and seemingly meaningless, and displayed all things in his museum with reverence for its impact on a personal level, not only its age or anthropological significance.

Morris Lupton is who we spend our time with, in his ghostly form, as he wrestles with the island’s ever-evolving character, now impossible for him to record and display. Time around him passes in wibbly-wobbly weeks at a time, as major events are held, as businesses and stories change hands and open and close in the blink of a ghostly eye. More fantastical still is Morris’s newfound ability to “cut in” to items, to pick them up and not only look at them but inside of them, through them, like an ethereal MRI machine that sees in full colour. Morris, and we, can see in fascinatingly thorough detail every item from the insides of an old CRT to a cross-section of the island’s tourist ferry to secrets even beneath the ground, waiting to be discovered in the living world by an archaeologist or shovel enthusiast.

Oh, and people’s memories. He can see those too.

In spite of his radical powers of examination, Morris has no way of taking this wealth of information anywhere with him. The museum is out of reach, both temporarily closed after his passing and likely not in the market for a non-living curator, if he could somehow continue curating after death. And so, in death, Morris explores Shelmerston and its inhabitants, from the island lifers to the native fishpeople, the mainland tourists, the parks and forests and everywhere in between, as he comes to realize that the beauty of life is in its gentle mundanity and ever-forward march, in the small moments you might only share with yourself, even if they won’t be remembered.

At least, that’s what I was hoping for the game to be about. The main crux of the game is that Shelmerston’s volcano, which has lain dormant for generations, has begun to exhibit troubling signs of getting ready to be about to very shortly erupt. As explained by Sparky, Morris’s also-unalive and now-talking dog, this is due to the island’s Custodian becoming weak after many years of keeping Shelmerston’s islanders safe. There are potential candidates to assume the position of Custodian, other notable deceased islanders who hold a special connection with the island and who may want to give up their ghostly lives or their desire to join their loved ones on The Other Side to take up the mantle of protector for years to come. You use Morris’s abilities to track down important personal objects and use them to find these potential Custodians.

The island of Shelmerston is delightful, and relaxing to explore. Each Custodian in your sights inhabits an area that is set up like a sort of living tableau, filled with characters who are gently bustling but not moving too much, going about their activities whether it is work or leisure, blissfully unaware of the ghost hanging around them and watching their every move. The shining strength of I Am Dead is in these daily details: watching a buoy salesman stand quietly at his stall in the market, waiting for customers to come; a game of cards in a construction site breakroom, left mid-game to resume working; a room full of plants, tended with care and prospering; a group of people doing yoga together during their morning routine. Wordlessly, you are able to imagine what happened before, and think about what might happen after.

At its best, I Am Dead is environmental storytelling on steroids. Instead of skeletons and guns and hackneyed mid-death notes, it is lunchboxes that you can peer into to see what someone’s favourite sandwich is, or a closet full of clothes that can send your imagination into overdrive picturing what taste and style a person might have. Being able to cut into a camera and see its telescoped lenses inside the lens mount, slowly zooming in to see each lens one-by-one, feels impossible and fascinating. Cutting away the ground to see tubers sprawling in soil growing doesn’t get old, even after hours. The world feels dense and populated, giving weight and personality to objects which might not seem worthy of even a second glance. In a real way, it helps with appreciation of the real world. Even if you can’t see it on the surface, there are so many wonderful things all around you.

At its worst, I Am Dead is Where’s Waldo, with Waldo holding your hand to tell you, hey, there’s Waldo. The structure of the game is as such: each maybe-Custodian has five people who have strong associated memories of the deceased, which are indicated with thought bubbles coming out of their heads. These memories, which play out as narrated stop-motion pictures, all concern an item that was important to either the ghost or the rememberer, and you have to find that item in the immediate area to advance the story. All of the game’s areas play out this way with (almost) no twists on the execution. There are also two lower tiers of item-finding: one of which is a page of riddles that correspond to certain hidden items in the area, and the second are the Grenkins, tiny island spirits which can only be found when an otherwise unremarkable item is cut and rotated a certain way.

These two feelings, one of relaxed exploration of daily island life and one of needing to find a certain item to advance, are directly in conflict with one another. There is an innocent voyeuristic pleasure to be had with I Am Dead, by design. Wishing to be a fly on the wall, as the phrase goes, isn’t uncommon in real life. Seeing how people act when they’re in their own environment is innately interesting. We people-watch. We wonder about the inner lives of other people. Sometimes, we even wish we could read minds. To be a ghost with the ability to not only sit in unaffected, but to delve into objects and memories, is fantasy fulfillment on a level much more personal than the typical video game power fantasy. It’s not swords and guns and murder and romance, but the appreciation of every person as human, as a life unto their own. It is the fantasy of being able to see somebody for who they truly are.

The design of the game seems afraid to fully embrace the fantasy that has been created, despite the cutting-in ability being endlessly entertaining. There must be dozens of lunchboxes with dozens of sandwiches, so many filing cabinets and workplace lockers, bird houses and fridges and desks and cupboards all with contents that hold nothing beyond exactly what is expected, yet the satisfaction of cutting into it to look at mustards or pencils or bottles of whiskey, and then cutting into those to see a cross-section from every imaginable angle, the satisfaction never goes away. The beauty of daily life is brought to bear through this, given form through an unreal process.

When it falls apart is when the game decides some objects are more important than others, and shouldn’t be missed. The urge to scour every nook and cranny of every room is hard to resist on its own merits, and that satisfaction is undercut when the game presents to you a riddle board highlighting every item that seemed like a hidden treat. Finding a bug inside of a head of lettuce in the fridge is gross and cute, and it communicates something about the world. The owner of this fridge desperately needs to clean it out, lest this lettuce bug infest other items in the fridge. Finding out that the later riddle is referring to the lettuce bug robs the moment of its joy, making it less of a discovery and more akin to the game running up and telling you to please please be sure to check that lettuce out, because we promise you’ll find something cool.

When Sparky alerts you to the existence of a Grenkin, a similar but arguably worse issue occurs. Grenkins live in everyday, boring, unremarkable items. They can only be lured out by cutting in and rotating these items to a certain angle, which is displayed to the player in the bottom right of the screen, pulsing and bopping steadily more until the angle is found. Not only does the game have Very Important Narrative Items and special hidden items to track down, it also has normal objects which it simply deems as more important, and urges you to check out. What makes this Bunsen burner more important than the Bunsen burner four inches to the left? How exactly does this thermos warrant special investigation when there have been dozens of them laying about beforehand? There is no explanation offered. All you know, through a pulsing audio cue, is that the thing you’re holding right now has an innate thingness that makes it thingier than other things around it. The lack of confidence in its core mechanic, how fascinating it is to see parts of objects which are otherwise hidden to us, undercuts the magic. I Am Dead takes away the player-directed sense of curiosity and puts systems in place to make sure that things are picked up and engaged with, either out of a lack of trust in players to want to enjoy the mechanic or a misguided attempt to wring every bit of use out of it.

As it goes along, I Am Dead changes its tune. It begins magical and supernaturally, letting the player lackadaisically pick up and peer through barnacles and pencils and desktops through no other prompting than their own intrinsic curiosity to experience these items. Once the story starts in earnest, it becomes a checklist to move down one by one, special items to be found and Grenkins to be collected, a hierarchy of meaningless importance enforced through collectibles for collectibles’ sake, and by the end it is clear that Shelmerston and Morris Lupton were only toys for the player to use, to hold up to the light and rotate around and go “huh, neat” and discard, checking the box on their list and patting themselves on the back for looking at the right thing. Any grand themes about individualism or humanity are passed by for pure mechanics, for a concentrated hit of Gamer Satisfaction™ because you looked at just the right thing in just the right way. The beauty of the simple life of the island is diminished. Important moments are earmarked in advance. Please listen to the audio tour. Admittance is $20. Enjoy the ride.