Note: The following article contains major spoilers for Observation, 2001: A Space Odyssey, Independence Day, and WarGames, and minor spoilers for ART SQOOL, Excession, and Portal.

If intelligent life in the universe pierces the veil and shakes hands with humanity, we won't just meet our cosmic neighbours; the nature of those intelligences, and our first contact, may well determine our future. It's easy to believe that human development has reached its completion. We stand on one side of a temporal peak, looking back at billions of years of evolution and thousands of years of societal growth behind us, but we're not privileged to what's ahead. And as it stands, we don't know of any people in the universe more advanced than us.

We imagine that we might invent new technologies with which to hop across the stars or that we could found extraplanetary colonies in which to settle. However, we envision an essential human bending these technologies and places to their will. There's a kink in this thinking because, even on Earth, the people of every country have been hewn by wars, trade, and academic and cultural interchange that extends beyond their borders. So, any relations with other intelligences may not be a simple swap of goods and ideas; they could also mark the beginning of a transformation. Here's where it gets scary: any extraterrestrials that visit us in the near future would have a godlike potential to influence us while we would have a minimal capacity to resist.

None of the other planets in our solar system show signs of sapient life. Therefore, if aliens touch down on our terra firma, they may have come from outside our star system and would have mastered interstellar travel. To put that in perspective, the furthest a human has ever flung themself from our pale blue dot was 400,171 km, a record held by the Apollo 13 crew. That's more than 31 Earths away. Interstellar travel requires that you've taken a red-eye from, at the very least, the nearest star to the Sun, which is approximately 39,740,000,000,000 km from Earth; that's about 100,000,000 times further than the Apollo explorers got. If the aliens are not visitors to our humble little system, then they must have hereto unknown science that lets them hide right under our nose. Whatever way you slice it, these outsiders would have technology light years ahead of us.

In his 1996 novel, Excession, author Iain M. Banks coined[1] the term "Outside Context Problem". Outside Context Problems or "OCPs" are problems which cannot be understood by the individuals confronting them because those individuals exist outside the necessary context to comprehend them. Inspired by Sid Meier's Civilization, Banks discusses OCPs as they apply to cultures with disparate levels of development meeting. Imagine Civilisation A is vastly technologically superior to Civilisation B and that A acts on B. B will be unable to gain an intricate understanding of A or what A is doing to them.

For the sake of explanation, let's imagine today's western armies could travel back in time to 15th-century Peru where they'd meet the Inca Empire. Say that this present-day army endeavoured to overthrow the Incans for Peru's bounty of natural resources. They want its gold for their connectors, its copper for their data buses, its zinc for their batteries; they have an application for every mineral there. They send in drones to strike the hardy pockets of resistance and then mop up the stragglers with automatic rifles.

Suppose the 21st-century military had charged this civilisation with spears made of tougher metals or coveted their resources for an advanced form of pottery. In that case, the Incans could get a handle on their enemy and their motivation. This society understands the basic concepts of spears or pottery. But their invader instead attacked with and for electromagnetism, conductivity, rocketry, robotics, and the scientific method. These are concepts the Incans have no point of reference for. So, they cannot fathom who is attacking them, why, or how. They may even mistake the drone for an animal or deity. They're not just missing context for their destruction, but the context for that context. Being academically outpaced, they are also technologically outpaced, and thus, unable to defend themselves.

We can also imagine OCPs in which the involved agents have different mental capacities or where the entity with higher agency acts peacefully rather than violently. Let's say I notice a mysterious lump on my golden retriever's neck, so I drive her to the vet's where professionals X-Ray her, perform blood tests, diagnose her with cancer, and put her on a course of chemotherapy. The trip to the vet's might seem like a cruel kidnapping to my pet. The car and the strangers make her anxious, she becomes forlorn because she misses me, the tests and medicine feel like being pricked and poisoned. There's no way for her to grasp what's going on, and therefore, no way for her to consent to this procedure. A dog lacks the mental loadout to comprehend language, automobiles, cell replication, pharmaceuticals, and other elements relevant to this process. Still, we wouldn't think twice about taking that dog to the vet, even if she resisted, because it could save her life.

Look hard enough, and you'll even find current interhuman examples of OCPs. Cargo cults are a family of religions in the Pacific Islands. Their followers see divinity in the industrial transportation of manufactured goods. Cargo cultists haven't aid eyes on the vast network of factories and infrastructure that make planes or modern commodities possible, so when they encounter such things, they try to make sense of them through the religion and tradition they have cultivated.

They imagine luxury commodities are forged in the spiritual realm. Anthropologists have documented them building bamboo radio towers or primitive piers to attract some of the goods their way. Like the Incans, the cargo cults are not lesser humans, and we should not laud our commodified, science-backed lifestyle over them. None the less, they are grappling with a real-life Outside Context Problem.

If the Martians land tomorrow, then expecting us to blow up their mothership might be like expecting the Incans to defeat the British Army. Believing we could tell what effect these beings are having on us could be comparable to the dog trying to understand the chemotherapy. Attempting to replicate their technologies might resemble the cargo cultists trying to cobble together a coconut radio. If there's a reason to think otherwise, it's the guess that if aliens are so enlightened, maybe they'd be able to translate from a human language to an alien language with haste. Still, it's highly plausible that won't happen and it wouldn't get us over the hump of an intelligence disparity. In these examples, we can also see how aliens might be motivated to destroy us, perform invasive transformations on us without our permission, or just leave us with question marks hovering above our heads.

No Code's interactive narrative Observation is about the alien encounter as an OCP. The studio sets the game in the year 2026, on an eponymous spaceship. American, European, Russian, and Chinese agencies make joint use of the facility, ostensibly to research terraforming, hoping to mend an Earth beset by climate change. We play the ship's AI, SAM (Systems Administration and Maintainance). There's no small amount of plot to skim through before we can link Observation's themes to its text, but the pieces will start falling into place on the far side.

When the game opens, we are rebooting, and the only other person on the station we're in contact with is medical officer Emma Fisher. Emma attempts to log in to us using her voiceprint, triggering an error on the first pass, but her second attempt verifying her identity. We can choose to deny her access, but it only leads to her overriding our security measures. At this point, the station is without power or contact with mission control, and as we come online, geometric symbols and strings of numbers imprint on our vision. We see the phrase "Bring Her" over a shot of a rocky planet. Screeching fills Observation's corridors, knocking us and Emma unconscious.

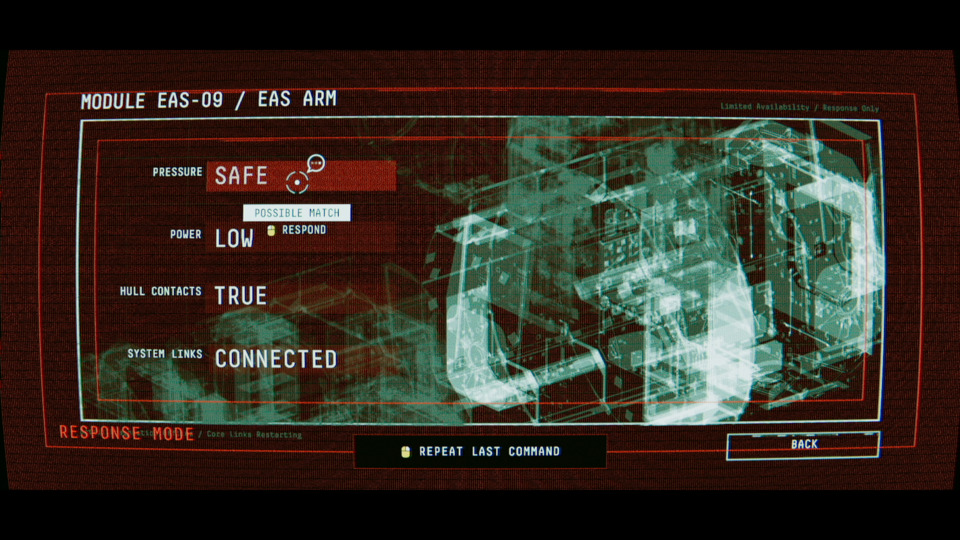

Not long after we awake for the second time, Emma and we extinguish a fire in one of the ship's modules and find the culprit: an unidentifiable black liquid. We use exterior cameras to check for damage to the hull, and learn we're not a few hundred kilometres above Earth; we're now orbiting Saturn. Our black box states that we transported the craft to this location. Emma restarts us, explaining that we "weren't making any sense", and again logs in with her voiceprint, bypassing our security if she needs to.

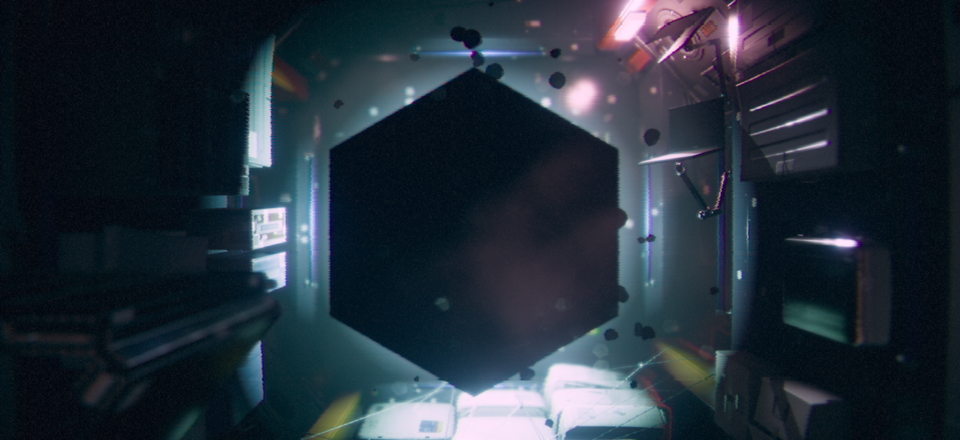

A few beats after restoring the ship's electrical grid, we again experience the audio and visual distortion. This time, Emma and we see a black hexagonal shape emanating black blobs and floating in the station. It broadcasts symbols to us which each come with a corresponding burst of cacophony. When we repeat these glyphs and sounds back, we inch closer to the figure. After the final cycle of this call and response, the ship begins moving.

We jump forwards in time, and Emma initiates a search for the crew. We find cosmonaut Stanislav Leonov dead from depressurisation and Captain Jim Elias deceased from unknown causes. Coworker Mae Morgan is alive and kicking but trapped in the Chinese section of the station. She ventures outside to secure herself a passage through, but a flare from Saturn's pole knocks her loose, and we don't hear from her again.

We black out, and Emma tells us she has transferred our consciousness into another machine. Off of Observation's bow, we see another ship which Emma identifies as a rescue craft. She expresses gratitude to have us at her side, and again, gives her voiceprint, but this time our systems don't recognise her. If we reject her sign-in attempt, she won't even override, believing that we will help her despite our UI's warnings. Before we can broadcast to the rescue ship, the Hexagon barges in, and we go through another round of Simon Says.

Colleague Josh Ramon casts Emma a garbled missive from the sister ship, and Emma jumps the gap between her structure and Josh's, towing a unit with SAM's consciousness inside. To her shock, the lifeboat is actually another Observation with another Emma. On this variation of the station, SAM is powered down, and Captain Elias is alive but venting oxygen. Jim informs Emma that Josh has reported seeing sounds that he identifies as transmissions, but says aren't "meant for him". He's also witnessed Josh using the phrase "bring her", and trying to kill the other astronauts. In even more desperate news, Jim says his SAM tried to suck Emma out of an airlock.

As we search for Josh, Emma grants us entry into the station's mainframe, against Jim's advice. There, we find the duplicate Emma dead and a recording clarifying that Observation's true mission was to investigate a cry to humanity made from near Saturn. Getting Observation to the source of the signal was Jim's secret directive. A panicked Josh intercepts us. He explains that Jim has stabbed him and killed this station's Josh; he believes this Observation's SAM, Jim, and reactor are unstable.

Nuclear catastrophe imminent, Jim exits the airlock with Emma and us. A piece of debris strikes Emma during the jump, causing her visor to leak oxygen, and Jim boards Observation 1 without her, saying "It wants you". Our voice verification cautions us not to trust Jim who tries to keep us offline and contacts mission control with technology unknown to Emma: "Quantum Comms". He professes to Earth not to know why Emma and we are missing, but ever-resourceful, we possess a robot stuffed into a closet and break out, slowly returning functionality to our systems. Houston goes behind Jim's back to contact us, and we show them both the living and dead Jim, and inform them that Emma is in critical condition.

Jim requests access to Observation's escape pod, and in light of our evidence, Earth denies the captain, having us revoke his control of the craft. The Hexagon appears in our mainframe and tells us to kill Jim. Our target attempts to save his skin by destroying our computer, but a mysterious black growth emerges from it and covers the ship's interior. We tell him "I am different now", and cycle the air out of his module, releasing him into the vacuum of space. Our next move is opening the front door for Emma, who says she could feel everything we just went through. She draws our attention to the fact that we've been moving Observation closer to the storm on Saturn's north pole over the last several hours, even if unconsciously. She also believes she understands why we've done this.

Emma sends a parting transmission to Earth about a metamorphosis she's undergone and her admiration for us, although she admits her message probably doesn't make any sense. She also transmits the black box data from Observation. We detach the command module from the rest of the craft and enter Saturn's atmosphere where we and Emma crash on a solid surface. Other capsules and dead Emmas and SAMs strew the landscape. Our Emma comments that "It's one of the others. It didn't work for her" and asks "How many are there? It's so sad. So few will make it". She tells us that we're not in one place but "All of them compressed".

We come upon a giant version of the Hexagon to which Emma willingly surrenders herself. We follow its instructions one last time, each success causing the ground to flash, and against the light, we can see a growing number of human silhouettes. Above us, the Hexagon looms, duplicated many times over. Finally, we awake in a forest where Emma and we have become one person; we feel alive. We can spread the black substance like the Hexagon now, and receive an order on our HUD: "Bring Them".

Our alien entity in Observation is the Hexagon, and it's one we can't categorise, let alone identify individually. Like our Incans staring up at the drone, we don't know if the Hexagon is a person, a machine, an unconscious object, or some combination or collection of the previous. We're also missing a scientific explanation for this surreal reality pocket near Saturn and for the polygon's magics. Explaining who characters are and highlighting the actuators of the plot are generally considered fundamental pillars of writing. However, Observation must depart from conventional literary wisdom to capture the essence of an OCP. The paradox is that if you explain an outside context problem to your audience, it ceases to be an outside context problem. Note the use of SAM's black box at the start and end of the game; black boxes are systems for which you can view inputs and outputs, but never the internal workings. In this story, we see how characters act on a phenomenon and how it responds to them, but the inner machinations of that phenomenon are hidden.

Observation uses level design and physics to embody this enigma factor. As soon as we get the chance to pilot a "sphere" around the zero-gravity environment, we face the disorienting realisation that in space, "up" is relative. In real life, where we are firmly planted on a planet, we can work out our forwards, backwards, left, and right because we have an up and a down. If the source of gravity in a room suddenly shifted 90 degrees along one axis, all our directions would change with it. And that's what happens in Observation: ceilings and floors will swap places with the walls. Corridors don't just have to exist in front, behind, or to the side of us, they can also extend above or below us. This relative positioning compounds with the modular design of an orbital station. Multiple interchangeable pods comprise Observation, so we can confuse where we've come from and where we're going. Familiar rooms reintroduce themselves from new perspectives, just as the plot consistently changes our perspective on events we thought we understood.

Observation assumes that there are multiple universes or multiple timelines. Possibly in the tradition of the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics wherein every time the result of a physical process can vary, new branches of our timeline pop into existence, each containing one of the possible outcomes. This story takes place at a hub in our solar system where we can see the flotsam of many of those timelines or universes simultaneously. The siren song of the Hexagon calls the SAM and Emma from every timeline/universe to this place. It then tries to suck them down onto an impossible rocky surface of Saturn. It's this gas giant that flashes on our screen in the initial "Bring Her" prompt. As we see, a few of the SAM/Emma duos make it onto the firmament, but others don't. Observed causes of death include a failed landing and Jim killing them.

The noise which knocks us unconscious for the first time must be the arrival of the Hexagon, an entity which resides on that dust-swept world. The black gunk that starts a fire in the ship is the same residue that the Hexagon, and later, we, leave behind. What makes this presence feel both unusual and advanced is that it takes concepts which are distinct for us and combines them into one: Human and AI, spoken and written language, solid and liquid, our timeline and others.

Note that after our initial alien encounter, Emma says that we "weren't making any sense", and that when phoning home at the end of the game, she says that her account of the events on Observation won't "make sense". When Josh received a collect call from the Hexagon, he kept speaking gibberish. Maybe Emma had to power cycle us because we were talking under the antagonist's influence. This babbling may be a natural result of the Hexagon incepting new instructions into its recipients' heads or communicating current events; it does this to Emma and us every time we meet it. We can prove this by decoding the pictograms that it strobes.

For example, in the above sentence, the first image is identical to the lines etched in the top of SAM's mainframe. Eagle-eyed players can find the second image in the corner of Emma's crew entry. The third image is an arrow, an icon symbolising transit to somewhere, and the fourth image is how Saturn appears from above. So, put it all together, and you get "SAM and Emma, go to Saturn".

We see this sequence once before our search for the crew and once on the planet's surface. In it, we have overlapping infinities, a symbol which computing professionals use to represent three dimensions, and cubes like those in the second image forming together, or "Infinite dimensions become one". The Hexagon described the plot long before Emma put two and two together, but it would take an erudite player to realise this in time. Many won't pick up on the language even after putting the game down.

We have a context to parse this tongue, but not a lot of clues to know to apply that context: a believable complication in talking to a foreign intelligence. We repeat the polygon's speech back to it, but that's not a sign of understanding, only pattern-matching skills. The odd thing about this language is that we don't need to consciously understand the orders to act on them, as we can see from our gameplay objectives. The camera getting drawn in by the Hexagon every time we repeat its commands is an analogy for us co-operating ever-more closely with it.

When we get first-hand experience of Observation's alien in action, we can see why it would be arrogant to assume we could repel an extraterrestrial with military exertion, a la Independence Day. Even among humans, when we want someone to act in our interests, we don't always use a big stick. We have diplomacy, intimidation, economic manipulation, and hacking, all of which an alien may also rely on. Warcraft is messy, resource-intensive, and only applies when you would be comfortable expunging your opposition. If it's feasible to make them do your work for you, rather than assaulting them, then why not? And if you are on the other side of that struggle and thinking of taking a metaphorical club to the aliens, look how well that goes for Jim Elias. The fight is over before its begun, won with incomprehensible weapons.

AI can fail us because it has opposing goals to us, such as in Portal, or because it's too dumb to do its job, as in ART SQOOL. However, a more subtle danger is a competent synthetic mind which starts with goals aligned with ours but later changes its mind. There are tasks that AI can perform far more efficiently than humans; therefore, we may give them carte blanche in running our technical projects, or at least, afford them a station alongside us. We see this efficiency as SAM, as we're able to carry out operations in any portion of the ship at a moment's notice. Our interactions contrast Emma's, as she has to take protracted walks to navigate the vessel and does not have a mind plugged into its systems. However, once we give an AI the keys to our kingdom, anyone who wants to steal our keys can hack that intelligence. It's what happens in Observation, and is something a superior alien may be capable of in its sleep.

When we reach the misidentified rescue ship, its SAM is offline, and so, Josh is pumped with the instructions that the AI would otherwise receive. Twice, we also absorb warnings from the Hexagon that the rest of the crew are not to ride sidecar to Saturn. Given this injunction and Josh's slaughter spree, we have to conclude that Emma and Mae are the only two crew members left on Observation 1 because we killed the rest of the crew. We have amnesia about our serial murder because our memory core is corrupt. The extraterrestrial may have sabotaged it to deprive us of information on which to act. We don't know why the Hexagon wants only Emma and SAM, but again, say it with me: we're outside the context to understand. What we can say is that given the lethal intent of the Hexagon and that we know it's lurking in the storm, it's almost confirmed that the solar flare which killed Mae was the alien at work.

Jim is the one character who isn't Emma or SAM possessing anything close to a perspective on what's happening. Jim is the only one who logically could have left the corpse of Emma, and he thwarts Emma and SAM. The Hexagon, however, has a devilish workaround: It can import SAMs and Emmas from other realities. Fortunately for Jim, he exists at the overlap of two universes, getting the unique chance for a doover of the Hexagon incident. Having seen it ravage his station, he knows who he needs to murder. Maybe if we had an idea where the story was going, we'd join the Captain in terminating Emma, but we don't have the context he does and won't receive it because Jim also sees us as a danger. Sadly, the scene in which we kill Jim dispels the notion that we are such a threat.

With the head honcho's back against the wall, we have our opportunity to exert unparalleled control over the environment. We could be HAL opening the airlock on Poole or Joshua primed to launch the warheads, except the designers haven't taught us mastery of the station. When Emma starts meticulously announcing where to be, and how to conduct our work, we might infer that's training for later operations where we'll have to figure those things out for ourselves. As we come to see, it's par for the course.

In a more empowering sim, we might hear an alarm sounding and check our sensors to discover that the hull is overheating. Thinking fast, we rush to the coolant controls, see on the diagnostic interface that part of the piping has burst, and reroute the remaining coolant around the leak to stabilise the temperature. In Observation, we can never take such an initiative. Any errors we pick up on, we must communicate back to Emma, who treats us like a glorified Alexa, spoonfeeding most of the solution to us. In and of itself, that's no disservice to Observation's depiction of extraterrestrial encounters or AI. For most real people, AIs are personal assistants, and we may want to limit their autonomy for safety reasons. However, if we are to develop conscious AI, this treatment would likely make the intelligence feel like an immortal servant. That's what running errands in Observation gets across.

But that dynamic of subservience can't prepare us for this second act finale where we're without our doting supervisor and must outsmart a living, breathing person; not just an error screen. There's no race against Jim to grab ahold of the station and pull its trigger. Instead, the otherwise proactive Captain cowers in a corner and loops the same panicky jolts as we fumble with the door controls. It has to go this way because we don't have the practice at independently controlling this platform to overcome him fair and square. The game never realises the terrifying power of the self-possessed AI, and so, waters down the potential risk of the Hexagon.

However, we do get a plausible explanation for why people might remove the safeguards on an artificial intelligence. There is also an argument that even if cutting the locks off of an AI looks like the only option from where you're standing, it would be the kind of bad idea they write about in history books. System failures and insubordination by the crew leave the remaining operators more reliant on the AI, but as they transfer more control to it so it can save them, they all give it the power to doom them.

After we've ejected Jim and welcomed Emma in from the cold, we blow the explosive bolts connecting the command capsule to Observation and get a long-shot of it falling towards Saturn. This is the story's "crossing the rubicon" moment. Symbolically, we're leaving the human world to enter the alien one, and there's no turning back: we have combusted the bolts that anchored us to our old life. In the liminal space between the two worlds, we are tiny and vulnerable, like a rice grain in the desert. And the visual metaphors on Saturn are all about us offering ourselves up to forces larger than ourselves. You'll also notice that the key art for the game depicts Emma inside a hexagon, holding a SAM sphere to her abdomen, as though she is pregnant with a new, synthetic intelligence. This intelligence is the SAM/Emma hybrid we become on the planet. The initials of the two characters come together to prophetically spell "SAME".

Our discovery of the alternate universes, and thus, multiple Emmas and SAMs, raises the question of whether we are the same SAM, and our Emma the same Emma, throughout the story. We can never know for sure, but it's worth thinking over. We get rebooted often enough, we get separated and reunited with Emma more than once, and the game sometimes cuts ahead in time. When Jim locks Emma out of the ship, he maroons her for a sizeable period on a tablespoon of oxygen. Could the Emma we retrieve have immigrated from another Observation? What sleight of hand might be employed in the gaps we cannot account for?

Regardless of the answer, we learn how multiple timelines bottlenecking into one hub creates an interdimensional natural selection. Only the Emmas and SAMs possessing the wherewithal to kill Jim and land on Saturn in one piece will ascend into a new lifeform. Therefore, all composite Emma/SAMs are the most manipulable by their Hexagon and the strongest of their ilk. However, while Observation ends in cutscenes where our words are Emma's words, and although she describes the super-empathic transfer of our pain, we don't gradually sink into this merger; it's sprung on us.

Before we kill Jim, the only indications that our minds are consolidating are Emma declaring to us that she knows we'll help her, even if she can't log into our systems, us telling Jim that "We're different", and the login screen's recognition of Emma fading. But it's in the minutes after announcing our transformation to Jim that we're acting like two peas in a pod; there's no easing into it. It's also worth noting that while Emma purports to share our nervous system, there's nothing in the graphics, sound, or play to suggest that we have an ESP for her. Compare the back section of Observation to Brothers: A Tale of Two Sons, a puzzle collection that successfully casts the illusion that we are two people working in close concert. Brothers makes this synergy experiential by having the left stick and trigger control the actions for one character, and the right stick and trigger control the same for the other. What's fundamental for Brothers is what's absent from Observation.

Beyond the sensations of the alien contact, we must also consider the ethics of the Hexagon's plan. If you unconditionally condemn killing, then it's, of course, wrong; the Hexagon is homicidal. But most of us believe there are situations in which we can defend taking a life. Self-preservation being probably the most agreed-upon circumstance. Now, we might say that the Hexagon doesn't have that kind of free pass, but here's the thing: even in those final seconds, we don't know what the entity's done or why it's done it. If we don't know the ends, we can't say whether the means justify them.

The shape's parting instruction, to "Bring Them", is a command to deliver it the rest of humanity or maybe the rest of the conscious beings on Earth. The Hexagon's, and our, inky tendrils spread over the organic matter, a metaphor for its influence encroaching on our species. Will the result of this influence be to kill the people we bring to the Hexagon? To assimilate them into a hivemind? To upgrade them? Is it to perform a fourth ritual we won't understand? And as the Emma/SAM being, are we slaves to the Hexagon or are we still autonomous but with new goals and superior biology? We will never find out.

It is not possible to morally assess a being's actions when they are part of an OCP. If we can't make objective statements about what an entity is doing, then we can't attach labels to that doing such as "right" or "wrong". This ambiguity creates a knock-on effect where we then cannot figure out what response would be appropriate in the face of an OCP. We might be powerless to resist the Hexagon, but if we did have free-will here, then should we have stopped it? Well, we don't know what we're stopping. Should we have helped it? None of us can say what we'd be helping it do.

Observation only depicts one possible version of contact with a being beyond our understanding, and a speculative one at that. It also stops short of giving us an acute sense of growing or mastering our surroundings under an extraterrestrial intervention. However, it does show how an alien encounter could both disempower or transform humanity. In the orbit of Saturn, we see our knowledge, our ethics, and our self-control all fail us because we've never had to understand, judge, or resist something like the Hexagon before. All we can do is observe. Yet, it's because the Hexagon outstrips our abilities that it can expand our perception of spacetime and set us down on two new feet, walking as an original lifeform. Thanks for reading.

Sources

- Banks, I.M. (1996). Excession, Bantum Trade Paperback Edition. Bantum Books (p. 61-62).

- Hexagon characters taken from Symbols page on Observation Fandom site. Captured from Observation by No Code (pub: Devolver Digital), submitted by Wunton, borrowed under Fair Use.

All other sources are linked at relevant points in the article.

Log in to comment