ARTificial Intelligence: Automation and Aesthetics in ART SQOOL

By gamer_152 0 Comments

Note: The following article contains major spoilers for ART SQOOL.

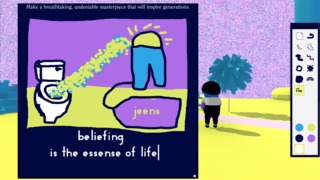

I am a blue, genderless student with a bowl cut and circular glasses, and on my trusty notepad, I've made a shaky, out-of-proportion sketch of a sun. The sun is wearing a pair of jeans and peeing into an open toilet. The caption reads "Beliefing is the essense of life". I jump off of a pink continent into a void of sprinkle static. A letter "Q" patterned like a migraine aura tells me my crude swiggling is acceptable and instructs me what to draw next. You see, I'm Froshmin, an aspiring painter at ART SQOOL, and I'm studying under the questionable tutelage of a computer program: PROFESSOR QWERTZ.

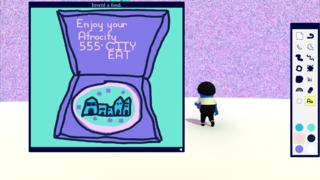

ART SQOOL is a sandbox developed by New York modeller and animator Julian Glander. It lodges us on a floating campus of bulbous shapes and loud colours. There, ART SQOOL's AI teacher has us take our best shot at painting in response to prompts of varying coherence. Our launchpads include "Draw something that makes you smile", "Invent a new country and design a flag for it", and "Draw a masterpiece that will inspire people for generations". That last one was the basis of my jeans opus. At hand-in, the professor scores our blotchy submission for "color", "composition", "linework", and "approach" before outputting a summary grade.

How could a string of 1s and 0s judge aesthetic quality? QWERTZ explains that the trick lies in it being a "neural net" trained on 100,000 teraflops of the world's most celebrated art. Neural networks are an emerging machine learning technology which has achieved results to turn heads. Machine learning relies not on explicitly telling a piece of software how to solve a problem but letting it extrapolate a solution from real-world data. The algorithms blossoming from neural nets can create a picture of a bird from just a description, beat top Starcraft players, detect congestive heart failure with 100% accuracy, and much more.

The optimism for these systems is bound up in QWERTZ, and more broadly, so is the potential of automation and the general technicalising of familiar tools. Machines can now perform jobs that once required a human touch like taking customer orders or packaging food, and in the coming decades, we can expect to see AI take to a growing number of career tracks. Today, computers run vending machines; maybe tomorrow, they drive cars; the day after that, they could be accountants; the day after that, they could be therapists. But something smells fishy in QWERTZ's claim that they belong to the same class of revolutionary machines.

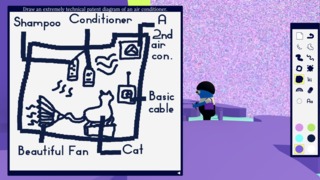

You could argue that QWERTZ is faulty because their instructions can be hard to respond to in a literal fashion. For example, when they task us with "drawing backwards" or recreating a famous cartoon character without violating copyright law. But this might be just the kick a student needs when they get too comfortable. Hazy guidelines get our right brains working overtime. If our teacher asks us to draw one still life over another, does that mean to paint one in the top half of the canvas and a second in the bottom half? Does it mean to draw one and then effectively erase it with another? Does it mean to print the first and then fill in the other over it in the form of translucent lines? Because the original request lacks specificity, the player must engage in personal interpretation which is the essence of art.

No, the problems begin when our painting ends. QWERTZ can claim to have digested 100,000 teraflops of data, but FLOPS aren't a unit of memory, they're a unit of processing speed. And as the semesters pass, a pattern of randomness surfaces in our taskmaster's feedback. We might painstakingly sketch our subject for one assignment and have the professor hit us with an "F", but phone in our next piece of homework and be bestowed an "A". QWERTZ doesn't even care if we deviate from their lesson plan. When they ask us to recreate a building on the college grounds, we could grab our favourite crayon and begin etching that house with the surreally tall stairs, or we could use that same implement to draw a cubist Vin Diesel. QWERTZ will give a passing grade to either.

Through QWERTZ, I'm reminded that, while there are ample success stories in the fields of automation and neural nets, Silicon Valley has a habit of writing cheques that their products can't cash. Theranos was a firm that promised it was on the verge of performing blood testing without a syringe; it was valued at $9 billion. Then, it transpired that the process never existed. Facebook keeps re-upping their intention to become a platform that allows users to mass-upload their personal data while protecting their privacy. To this day, they don't appear to have any idea how to do that. General Motors, Honda, Tesla, Toyota, and Waymo (a Google company) all said they'd have self-driving cars on the roads by 2020. It's late 2020 at the time of writing, and they're nowhere to be seen. There's still no anticipated date for their release.

Then there are the specious claims that existing practices are inherently upgraded through being computerised. Juicero was a tech startup that launched to the tune of $120 million raised from investors such as Google. A digital upgrade to the analogue juicer, Juicero cost $400, could only interface with pulp bags manufactured by the company, and a human could squeeze the drink out of those pouches anyway. They had a friend in Reefill, a service aiming to take the free utility of water fountains and demand you use a smartphone app and paid subscription to access them. There is a whole "Internet of Things" made up of devices you already know but with an online connection. However, that connection can compromise users' personal data or security for frequently nebulous benefits. Else, these appliances can spontaneously break because they can no longer reach their servers.

It's not that you might never be able to extract blood without a needle or power boost your fridge. The point is, for purposes of marketing and pitching, "disruptive" electronics producers tend to overstate their abilities or treat any technology's existence as self-justifying. After all, you're not going to make sacks of money underhyping your product. QWERTZ is an artefact of that value inflation: the art tutor supposedly elevated through a brain full of transistors, but in actuality, a poor imitation of its human counterparts.

Art appreciation is not a task that can be automated. Artists creating for spectators do so to evoke thoughts and feelings in an audience, so if the viewer cannot think or feel, the art will not be appreciated. Could a machine be conscious? Maybe, but consciousness won't arise from a neural net and some JPEGs of Vermeer. I'll admit, even if QWERTZ can't be an appreciative viewer, that could be irrelevant because its job is to be a teacher. We can imagine an AI getting that right, but this one doesn't. This program's engineering is deep, but that doesn't mean its output is.

The professor gives us five different scores that express where our paintings please and where they fall flat, but it could rattle off a million scores. If we're not cognizant of how it calculates those metrics, then we don't know how we could change our art to improve them. To understand how we take any measure is to know what that measure is. If you don't know that we test hertz by checking how many times an event occurs per second, then you don't understand what hertz are. If you're unaware that we work out pascals by looking at how hard something is pressing on something else, you don't know what pascals are. The method of evaluation is the definition, so if we don't have a general idea of how the good professor analyses composition or colour, those variables don't mean anything to us.

Here's another way to think about it: It's common wisdom that the more data we have about something, the better we understand it, but ART SQOOL demonstrates that that's not always true. QWERTZ can tell us that our approach is winning or that our linework needs improvement until it's blue in the CPU. If we don't know that its output is the result of an informed evaluation or we don't have an idea of how we can act on that data, it's just flack. Constructive criticism always suggests actionable steps for a creator. Imagine knowing that "linework" negatively correlates to how wiggly our strokes are or receiving more qualitative feedback like a reminder not to get too hung up on symmetry. With this information, we would have strategies to put into practice on our next assignment. But what we get are swelling columns of colour where actionable feedback should be.

It's possible that, at least within the fiction of the game, the AI's analyses are not truly random, just based on an unpredictable algorithm. But without written advice or context for any of its grading, they're functionally random from the perspective of the student. While humans can often verbalise what bothers them, computers sometimes act as black boxes, giving us ambiguous warning lights or error codes which obfuscate the underlying issues. But try to picture a QWERTZ that shatters that communication barrier and a more entrenched problem emerges.

Before we can imagine what a cogent and objectively accurate conversation about our artistic skill might sound like, we'd have to decide what an objectively correct approach to art is and be able to express that approach mathematically. Because, if you can't write out a process in arithmetic and logical terms, you can't get a computer program to apply it. ART SQOOL's dean is not a bungled implementation of a concrete theory. Instead, it's unclear what the theory that would back an art AI teacher would be. Developing intelligent AI is often not just a matter of the right engineering, but also the right philosophy. This premise is most commonly explored through lingering questions over ethics, but ART SQOOL highlights another alcove of philosophy with implications for artificial intelligence: aesthetics.

Again, to understand a metric is to know how we'd calculate it, so if we can't write an algorithm to quantify the validity of a piece of art, we can't make objective measurements of the quality of any art piece. We'd need a beautyometer in the same way that scientists have designed barometers or voltmeters. If QWERTZ is that beautyometer, we wouldn't know because they don't show their working, but the idea is ludicrous on the face of it. What equations do you run to determine how fun the use of colour in a picture is? Which operations would you have a processor perform to tell you whether the Mona Lisa or The Great Wave is better?

These play more as jokes than the tees for any academic response, and those are the jokes that ART SQOOL is telling. There's an amusement in the reductionist absurdity of taking anything from a kid's watercolour to a Kahlo and sticking a C- or an A+ on it. This is why it's hard to take seriously the idea that current or near-future tech and automation are panaceas, or that we can generate "objective" ratings for art. It's particularly worth mentally returning to ART SQOOL when we see a score on a review or use a service like Grammarly which attempts to use a number to represent the value of a creative work. Are these just more "Q"s giving my wireframe frog a D-?

Of course, now we're tapping into a universal aesthetic problem that even a human can't entirely overcome. Because, if there is no objective art assessment, then why go to art school? If you're not always going to know why a teacher gave you the grade they did, how do you value their opinion or learn how to alter your work to please them? Most of us have had that experience of believing we nailed an educational assignment and getting back a disappointing grade or turning in a project that we think will scrape the bar and finding we got decent marks. ART SQOOL emulates that experience because a driving theme in the game is uncertainty.

The randomness of the scoring means that we can't know whether we're doing the right thing at any one time or if we can fully trust our teacher. Through their songs, Froshmin also conveys doubt that they're at the right place in their life. In the game's ending, the protagonist's only lines are asking QWERTZ what will happen if they can't hack it as an artist, post-graduation. With its out of tune skybox, its disjointed floating islands, and its abstract, blobby structures, you never feel like there's too much solid ground to rely on in ART SQOOL. You'll probably fall right off the map at least once or twice. And I'm not an artist, but every one of them I've followed online seems to live with this occupational uncertainty; no matter how talented, they can never be sure the world will return on the graft they put in.

However much effort we dedicate in this game, the crayon box that the designer gives us is too unruly and diluted for us to act as PC monitor Picassos. Our toolset can only be described as a vaporwave Microsoft Paint. Its palette consists of black, white, and three garish colours, and the only drawing implements we get are fill tools and some thick, free-form brushes. With a steady hand and a tablet, you can sketch something respectable, but most users are going to have one hand on a mouse, and even for the professionals among us, there are limits. Chances are, your ART SQOOL projects finish up as squiggly, smudgy messes. We are roleplaying someone still learning to paint; therefore, the products of our craft are not going to be museum grade.

So, do the randomness of our success, and Froshmin's underdeveloped abilities make ART SQOOL pointless? Do they make art school pointless? I don't get that impression from the game. Most artists aren't in their field to "win", they're there because they want to feel creative, express themselves, and bask in the satisfaction of a job well done. Our score in this sandbox is uncertain, whatever action we take, which means we're freed up to take any action we want, relieved of the worry that it will lower our chances of scoring high. By unshackling us from explicit objectives, ART SQOOL becomes a white space where we get to flex our creative muscles. And sure, we can't leverage those muscles to scrawl more than doodles, but without the capacity to create a masterpiece, there's also not the pressure to do so. There's something of developer Julian Glander's original art in these tools: the pictures come out noodly and bitesized, but are none the less, charming.

I'll cop to being an abysmal painter and someone who would never normally embark on a lot of freehand drawing, but there was enough structure and forgiveness in ART SQOOL that I was motivated to throw caution to the wind and put a pen between my fingers. And whatever the professor says, the more we make, the better we get at making. ART SQOOL suggests that the point of art school is not to get a scientific reading on the quality of our art and that the professors cannot do our learning for us. It also floats the idea that more technology will not intrinsically improve academic assessments of aesthetics. It states that developing as an artist is a sole pursuit and that we should temper expectations for near-term digital solutions to any complex task. They will not guarantee success. There will never be a guarantee of success when we make anything.

However, in ART SQOOL's opinion of art school, performing our assignments is worth it because it helps us grow as creators, and lets us do something worthwhile. So, when I finished all my homework and got my graduation cap, I hadn't painted anything anyone would hang on their wall or transformed into the next Rembrandt. But I'd done something more important: I'd made art that I liked, and I didn't need another person or a machine to tell me that I should like it. As Mr. Rogers said about drawing, "I'm not very good at it, but it doesn't matter. It's just the fun of doing it that's important".[1] Thanks for reading.

Sources

- Mister Rogers' Neighborhood. Season 11, Episode 9: Mr. Rogers Talks About Competition (II) (June 1, 1981). Directed by Hugh Martin. Fred Rogers Productions.

All other sources are linked at relevant points in the article.