Principles of Design- Characters

By Daneian 7 Comments

First impressions are tricky things. You are introduced to every character as you are every person- without context. You might have seen pictures of what they look like, heard of their stories, but until you see them with your own eyes, it’s all academic. There are only two qualities about any person that can absolutely be measured- their existence and their actions. Their motivations and psychology are nothing more than conjecture and speculation but that doesn’t mean they’re not important.

A character is any fictional entity that possesses a behavioral system and the capacity to act in relation to other entities. Sentience, or the appearance of it, is crucial as it is a requisite for the state of being alive, so frees the definition from being exclusive to human beings. A story isn’t one without characters who are acting to accomplish a goal, often in direct opposition to others. Constructed well, a character is cognitively indistinguishable to the observer from a person of flesh and blood; even though you will never meet one, shake its hand, they become friends and enemies. As we witness the unfolding events, characters become our emotional anchors- we cheer when they fight, celebrate when they win and mourn when they die.

Since every person is a combination of traits both physical and mental, an author must fully understand who their character is, what it wants and what it will do to get it. Successfully building a character completely depends on implementing the thousands of ways which everybody communicates information about who they are, even when their mouths aren’t moving. This information is characterization and every bit reveals history.

Even if a person is born at the moment we meet, their physicality is full of detail: we can deduce lineage from the structure of their bones, the color of their skin; as they grow, we can reason out their diet from its shape and constitution; we are given a recording of their experiences from their musculature, from their scars; and we get insight into their emotions from how they conduct themselves, the efficiency of their movements and the strength of their voice. At any point in a life, the evolving shape of a body is the product of the confluence of events that led them to that moment.

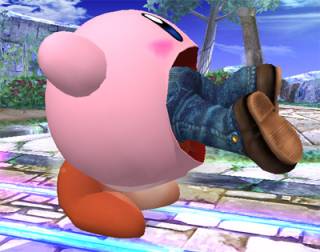

And a form dictates capabilities. In videogames, that form is the foundation for the mechanics the gameplay is built upon. One of the more classic correlations can be found in the size of the body- small and quick, large and strong. But, form doesn’t necessitate shape. Look at Kirby, the cotton-candy pink puffball whose defining ability is to swallow others and steal theirs- a single ability that has the potential for all. And yet, a forms consciousness doesn’t have to be limited by a body. Halo’s AI Cortana may be able to project an image in order to interact with Master Chief, but she is composed of light and data clusters and can access and interface with networks throughout the universe. Though she has her limits, she isn’t confined by physical constraints. Form dictates capabilities- don’t confuse it with appearance. That serves an entirely different purpose.

Information theory deals with how humans identify, analyze and interact with a thing on a psychological level. A tenet of the study declares that for any design that intends to be used, a tools core application and utility should be discernible by looking at it. When applied to videogames, that means the observer must be able to intuit a characters core mechanics and abilities by looking at them. We can assume that if it has wings it can fly, has a mouth it can speak or holds a gun it can shoot.

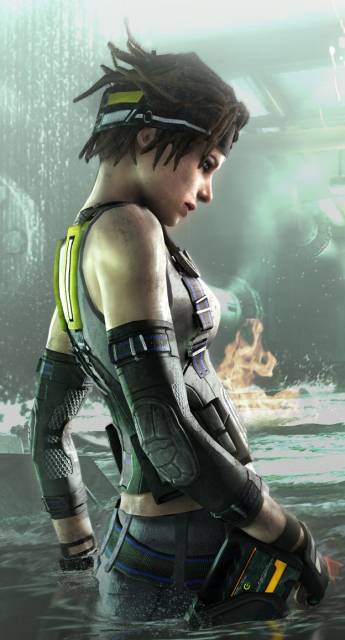

While functional design communicates a character’s proficiencies and relays characterization, it also sets our expectations. When thatgamecompany developed Journey, they weren’t going to allow the player to lift objects or grab a ledge if they missed a jump, so shrouded their protagonist in a large robe to obscure its figure, excising many assumptions and imbuing movement with a sense of speed in the process. But just because a design can communicate gameplay potential and characterization doesn’t mean it’s appropriate for the context. In Dark Energy Digital's Hydrophobia, fashion-backwards protagonist Kate Wilson dresses like a rock climber for her job as a security engineer, apparently awaiting the day the colony ship where she is employed will get attacked forcing her to climb, swing and vault through the wreckage to safety. That’s poor design that only gets it half right. Character design requires acknowledgment of the body but must also reflect the content of the mind.

And the mind is a much more complex matter to construct. When it’s young, every mind collects data on the nature of reality and contemplates its place within it. It develops a value system based on the conclusions it’s drawn and a moral code to direct its actions. It forms a philosophy. But that philosophy can be challenged over the course of a life and people can find themselves re-evaluating the conclusions they’ve held, even if those ideals had formed the basis of their entire way of life. There are many stories where this is the point, to grow and mature. For many others it’s just the start- theirs is a journey attempting to fulfill a goal that’s acceptable to the morals they already hold.

The desire can be any object, person, event or idea. The path that leads a character to their goal is plot and every step down portrays characterization. If the goal is set and directed by forces outside the character, they have little emotional tie to its success and are instead swept up in the momentum until its conclusion. If they set off on a goal they established for themselves, they must care about achieving it and their persistence and ferocity to clear greater and greater obstacles tells us about who they are and what they’re made of. Somewhere in the middle of those two types of plot are the ones that have been brought directly to a character because of their profession. These plots are about one character stopping another from reaching theirs and are the most frequent types of stories you’ll find, regardless of the format.

For their connection to the observer, these plots also start at an emotional disadvantage. We know that we connect with characters because of plot and that plot is infused with characterization, so we must ask ourselves what we get attached to in these stories and why. For mysteries, the answer is simple- the criminal. Though it adheres to the same basic rules, the emotional connection is different; rather than celebrating a hero for reaching their goal, we fear that a villain will reach theirs. A criminal has reason for breaking the law- the need to feed their family, an unquenched desire for revenge or for the sheer thrill of it- and through it we get a sense of who they are. In opposition is the detective, whose plot is to bring the criminal to justice or keep them from committing more crimes, a plot that tells us very little about who the detective is on the inside. We only get characterization from the means they use to catch the criminal. We can assume that, as people who entered the trade of their own free will, they must generally care about the process but they are in no way required to have a vested interest in the outcome of a single job.

This often creates a complex dynamic between characters within a story. The main character in any narrative is the protagonist, but that in no way means they are a hero. Every relationship is relative. People tend to be friends with those with shared interests, whether it’s having the same philosophical views, enjoying the same activities or trying to keep from being alone. In a similar vein are enemies, who usually stand in opposition of any of these areas that would have brought them together. Regardless of their role in the narrative, they all affect the pursuit of the plot- they can be the one that embarks on the quest, be the object at its end or be the blockade trying to impede it. The difference between the protagonist and antagonist is one of perspective.

In the hundreds of thousands of years of human development, physical and behavioral patterns have emerged. Our brain recognizes these patterns and organizes them into stereotypes which it uses as a cognitive shortcut to quickly identify the behaviors the next time we confront by them. Collections of these stereotypes form archetypes, a more integrated roadmap that allows us to quickly sum up an entire personality and assess how to approach them. We use similar types of mental shortcuts for everything from driving through traffic to shopping. For storytelling, these archetypes are useful as preset traits that allow us to identify what role they will play and how they will act. To illustrate, let’s use a reporter, a detective, a scientist- three professions with different fields but similar methods and aim. They all gather information, make deductions and search for truth but it’s not until you see each in their respective environments- a newsroom, a crime scene or a lab- that you know the difference.

Nobody behaves drastically out of character; if they appear to its only because we had the wrong impression of them in the first place. Even if a character has conflicting personality traits or behaviors they must remain consistent to the whole. Take The Joker, a character of pure insanity who often acts without reason; he can be cruel, playful and serious and all are consistent with his defining characteristics- unpredictability and chaos. But mechanics must also be consistent with a character or they run the risk of seeming superfluous. Max Payne can enter bullet time, a state of hyper awareness that appears to slow down time and allows him to move quicker than his enemies. Where it falls apart is that the ability doesn’t seem to be attributed to Max as a character since any player can do it in the third releases multiplayer. The mechanic also isn’t consistent with bursts of adrenaline because the painkillers he downs don’t hinder his perception or reflexes. Here, Bullet Time is a mechanic in service to style rather than characterization. This is an example of ludonarrative dissonance, an idea that deals with any disparity a videogame has between the mechanics of its gameplay and the devices and actions used in its narrative. It’s also found in every entry of the Uncharted series, where the affable Nathan Drake kills thousands of people as he seeks treasure and fortune.

That means that for videogames to cohesively weave gameplay within a narrative, the central mechanics must complement the plots goal and be consistent with the characters abilities. Solid Snake is a master of infiltration and over the years has broken into maximum security facilities, stolen intel, rescued hostages and disappeared without a trace. As Metal Gear allows the player to slip past enemies undetected, the games mechanics are built to accommodate for stealth- Snake can peer around cover, distract guards, and crawl through vents. When the situation calls for lethal force, his training in weapons and unarmed combat as a soldier help him make it out alive. These are mechanics inexorably tied to Snake, ones that are consistent with his expertise and appropriate for the missions normal people would fail. That is complete characterization.

It’s at this point that we realize what function a character truly serves for the structure of a story. As every person is a collection of beliefs that evolve into a moral code and acts within its confines, all characters are inherently devices for promoting their respective philosophy in relation to the story’s plot. They are the workings of that code abstracted into a physical, but still conceptual, form. The one who wins in the struggle, and how they conduct themselves to overcome it, are the author’s commentary on which ideas and ideals are the correct ones to hold- it’s their statement that this philosophy beats that philosophy. The reductionism of that statement can seem a callous insult to characters that we love, but there is no limit to the size, scope and landscape of the ideals a character can represent.

While living people change and grow older, most characters are created and exist in a vacuum. No matter how many times you read the same book, watch the same movie or play the same game, the character doesn’t change. For the ones that we remember fondly, the relationships we cherish, they show us a world we hadn’t ever seen before, and that’s incredibly powerful, since it’s their actions that linger in our minds. We meet them and when they’re gone, we are different than we were before.